I have always had a morbid fascination with canals. There is something sinister about the unnatural way they snake into towns and cities, often hidden between and beneath buildings. The water is always murky and impenetrable; it could be three feet deep, it could be ten feet deep; the latter is, of course unlikely, but the awful possibility remains. I associate canals with death. Dead bodies. People who have had enough. Rivers are capricious things. They flow, they run shallow, they run deep; they are unreliable. But the canal is different. For someone contemplating what is surely the most awful method of suicide, drowning, the canal offers stillness and silence. The canal will be unlovely, unvisited, and a place where the past hangs heavy. For a killer, wishing to dispose of a body, the same attractions apply. Even as I write, an urban legend grows in strength. People believe The Manchester Pusher is a serial killer (click the link to read the story) who haunts the cold, bleak and dark canal network that runs through the city. There are few lights along the canal towpaths. There is no-one to hear you when you scream. Figures from the Manchester City Area coroner’s office show there have in fact been 35 drownings over the past decade. Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service (GMFRS) say there have been 22 such deaths in the city centre since 2009.

Wisbech had a canal. It was dug out of the Fenland soil in the dying years of the 18th century, and was relatively short, but connected the tidal River Nene with the Great Ouse and was, in its prime, a way to transporting the valuable fruit and vegetable produce of the Fens to the coast, and then onward to other markets. In 1853, the canal remained a viable thoroughfare for farmers. merchants and traders. It was also still enough, cold enough and deep enough to embrace human bodies in its watery arms.

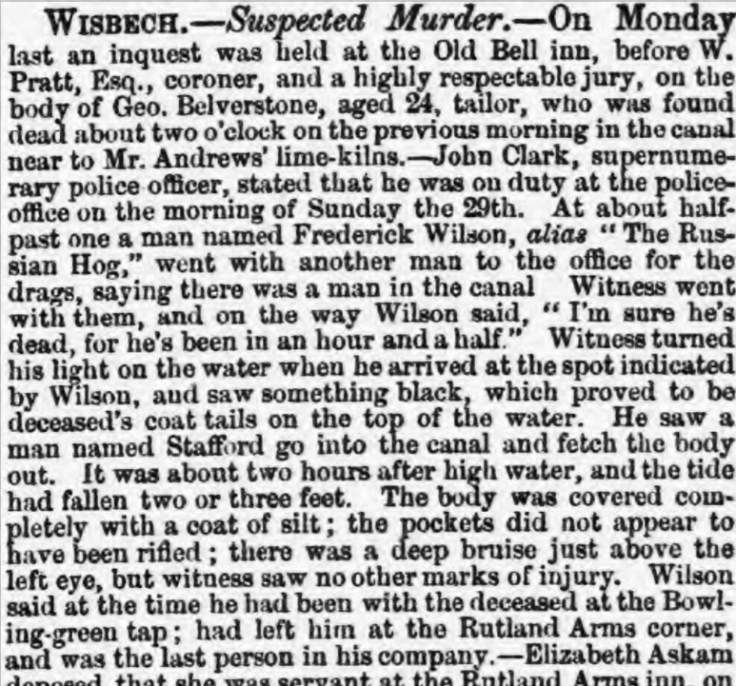

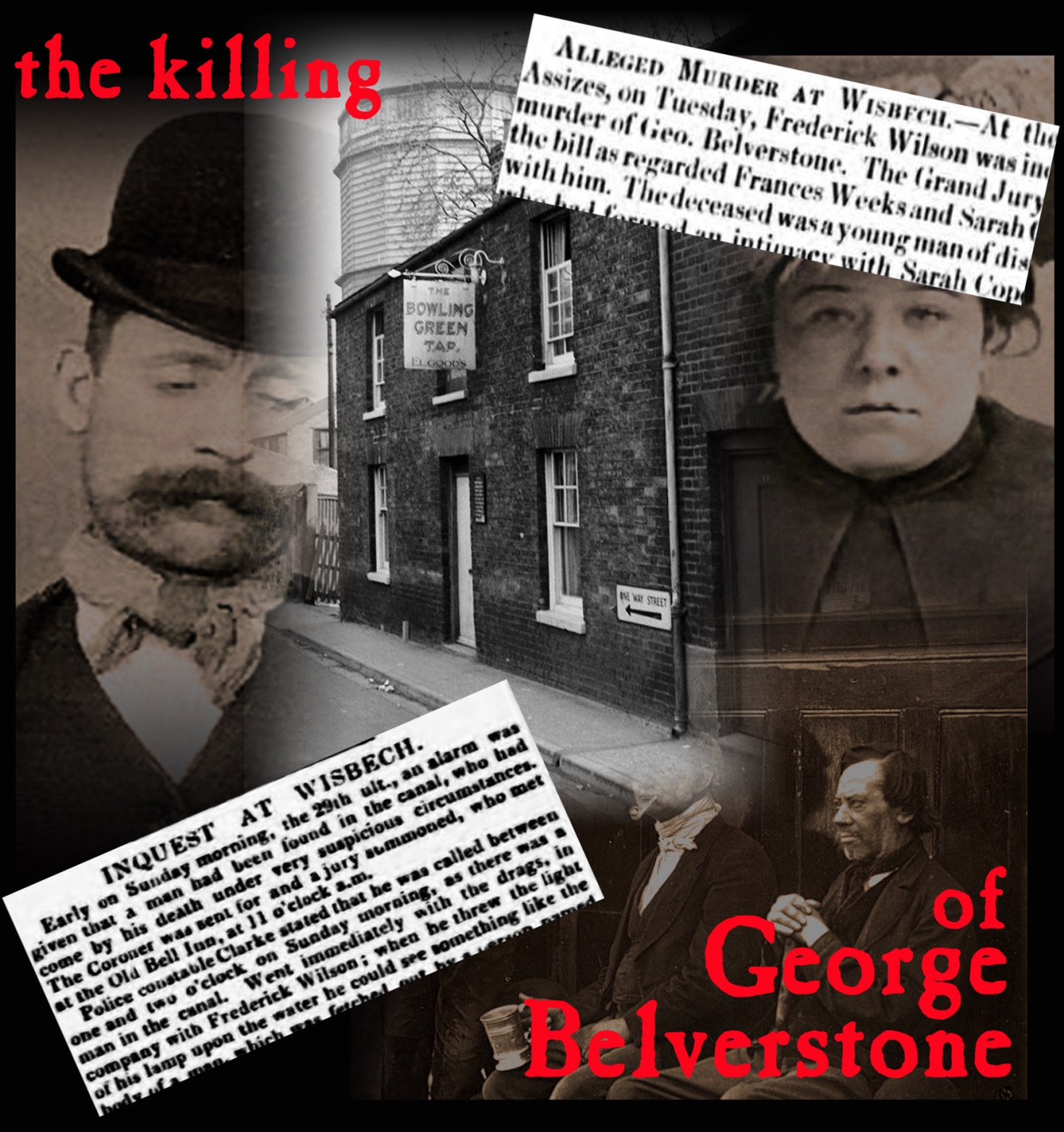

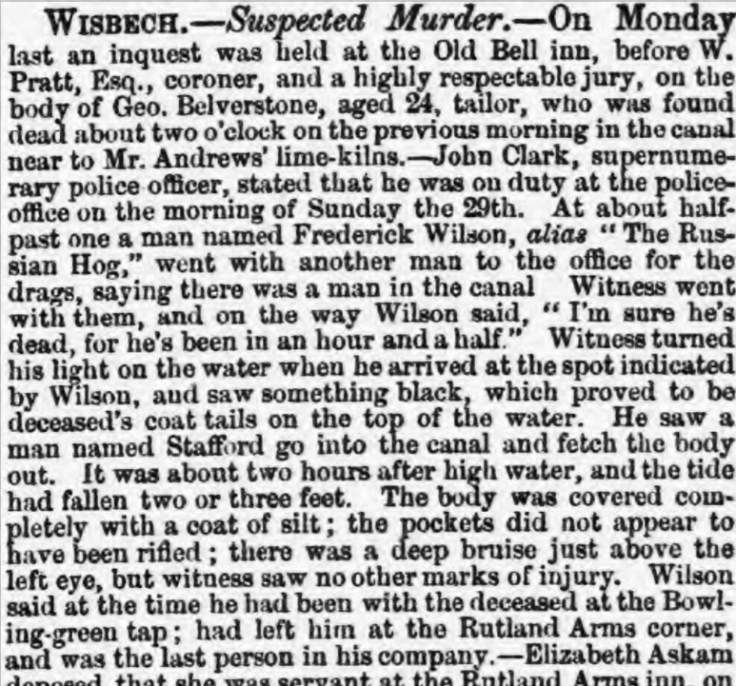

In the grey dawn light of May 29th 1853, a body was found floating in the canal. A witness at the subsequent court case stated:

“I heard someone shout, “There’s a man in the water.” I did not get up until I heard someone say, “It’s young Belverstone!” I knew Belverstone well. I knew Wilson by his nickname ‘The Russian Hog’, but I was not well acquainted with him. I had been brought up with Belverstone from a child. When I heard the cry that he was in the water, I went downstairs and went to the canal side. I then saw Wilson, with several other people. The body was out of the water, and on the bank. I asked Wilson to let me see the body, but he refused. When I asked him who it was, he said, ‘Young Belverstone.’ I asked to see his face, but Wilson said, ‘No – you are a female, and don’t want to see him. When I afterwards saw the body, it was young Belverstone.”

Frederick Wilson, as his nickname might suggest, was a fearsome local brawler. Built like a heavyweight, he held court in several Wisbech pubs. Belverstone, (24) was not unused to pub life, as his father, William, was landlord of another local tavern, The Wheatsheaf.

It seems young George had been drawn to Wilson’s circle of hard characters and female hangers-on, but they saw him as gullible and a prime target for jibes and jokes at his expense. Again, another witness statement from Wilson’s trial for murder:

“At about one o’clock, I was in bed, but woken up. I thought the noise was in our yard. People were laughing, larking and scuffling about in the lane. I went to the window to look. There was a gas lamp in the lane, fifteen or twenty yards from where I was looking. I saw the prisoner and Belverstone, and two women. I didn’t know the women. I saw Belverstone knocked up against Mr Oldham’s door by Wilson and the two women. They did not appear to be angry, but seemed to be all larking. I then saw young Belverstone knocked down on the ground several times. I don’t mean knocked down with fists, I couldn’t see that. They all kept about him larking. He was pushed down three or four times, and then they helped to pick him up, as far as I could see. One of them kept saying, ‘Pick him up, pick him up!’ I don’t know that he was drunk. Once, when he was knocked up against the door he cried out. I saw Wilson strike Belverstone once or twice, but whether by the fist or the back of the hand I cannot say.”

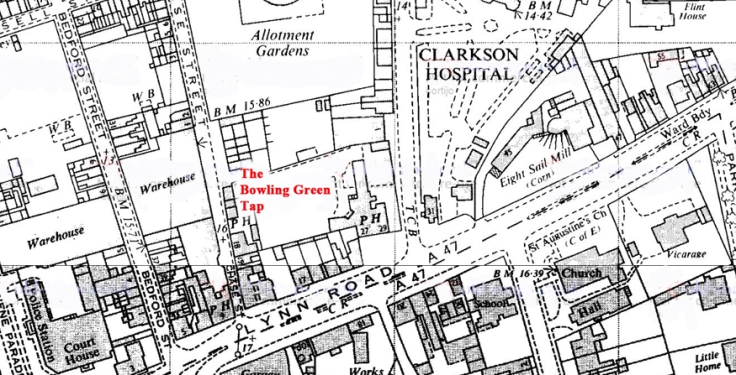

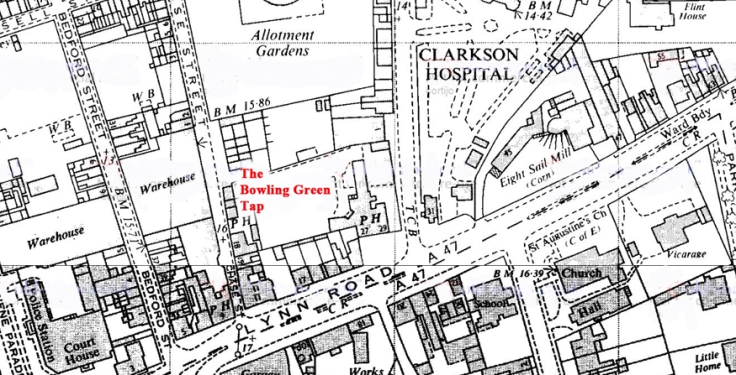

Belverstone’s fatal final evening had been spent in a back street pub called The Bowling Green Tap. It was demolished in the 1970s, but local people still recollect it fondly:

Back in May 1853, it seems that the hapless young Belverstone had supped well but not wisely. He had chosen the company of people who sought entertainment through his vulnerability. In court, the evening’s merrymaking at The Bowling Green Tap was described thus:

“I left about six persons in the house. Belverstone was drinking, and was not sober. He was so tipsy that he fell off his chair, but did not hurt himself.” Mr Power asked, “How would you know?” Mallet replied, “I fancy he didn’t.” The judge asked, “Was he so tipsy that he couldn’t sit on his chair?” Mallet said, “Oh he could sit very well, and he was laughing to see another man so drunk that he fell down.” Mr Power then stated, “Ah, so one man was so drunk that he laughed so much at another drunken man that he could not retain his seat!” Mallet said, “Yes, but there was no quarreling when I was there.”

It seems that Belverstone was struck down by Wilson, who was clearly acting up to impress his female entourage. Somehow Belverstone ended up in the canal. Wilson was arrested and detained on suspicion of murder. His trial was held during the Cambridgeshire Summer Assizes in the July of 1853. There were two key questions which needed answers; Did Belverstone drown, or was he killed by a blow from Wilson? How did he come to be in the canal?

The local surgeon who carried out the post mortem on Belverstone provided an unequivocal answer to one of the questions. He said that the dead man had received a violent blow to the skull, just behind the ear, but saw nothing to indicate death by drowning. As for how Belverstone found his way into the canal, a prisoner called Peter Brett who talked to Wilson while he was on remand seemed to solve the mystery.

“I have known Wilson for two years. I am a prisoner from Wisbech. I met Wilson in prison. He asked me how long I had to stop. I said I was in for a month, and asked him what he was in for, and he said, ‘murder’. He said no more that day, but I saw him a few days after (the 5th of June) and he said, ‘ I have thrown a man into the river.’ I asked him what man, and he replied, ‘George Belverstone.’’’

After an elaborate summing up by Judge James Parke, 1st Baron Wensleydale, (left) the jury retired to consider the precise cause of Belverstone’s death. Not for them days of deliberation, or purdah in some hotel away from the public eye. After a full five minutes, they returned and the foreman stated that George Belverstone had been killed by a blow from Wilson’s fist. The prisoner, at this point, must have had visions of the hangman’s knot swimming before his eyes, but the 1st Baron Wensleydale was minded to differ. Unbelievably, he was of the opinion that although Wilson struck the fatal blow, “the violence was attributed to accident,” and pronounced:

After an elaborate summing up by Judge James Parke, 1st Baron Wensleydale, (left) the jury retired to consider the precise cause of Belverstone’s death. Not for them days of deliberation, or purdah in some hotel away from the public eye. After a full five minutes, they returned and the foreman stated that George Belverstone had been killed by a blow from Wilson’s fist. The prisoner, at this point, must have had visions of the hangman’s knot swimming before his eyes, but the 1st Baron Wensleydale was minded to differ. Unbelievably, he was of the opinion that although Wilson struck the fatal blow, “the violence was attributed to accident,” and pronounced:

“Frederick Wilson, I quite approve of the verdict of the Jury. You have aggravated your offence by adding the guilt of falsehood to your crime of having deprived a fellow creature of life whilst in state of intoxication; I punish you now only for the blow inflicted ; It does not appear that you were in state of anger at all, and there are other mitigating circumstances in your case. I therefore sentence you six months’ imprisonment, with hard labour.”

Six months in jail for killing a man? I believe that those who rail against what they see as the soft sentences handed out to modern criminals should study legal history. The law is, always was, and ever will be – an ass.

My thanks to the members of the Facebook group Wisbech Pictures Old and New, particularly the family of the late Geoff Hastings, Andy Ketley, Roger Rawson, Steve Williams, Andy Ward, Patricia Warden and Pat Prewer for their photographs and memories.

This very English mystery revolves around the death of a distinguished biographer, Ralph Maguire. Maguire is in the terminal throes of dementia, and in his moments of lucidity he is trying finish his book about a celebrated actor.

This very English mystery revolves around the death of a distinguished biographer, Ralph Maguire. Maguire is in the terminal throes of dementia, and in his moments of lucidity he is trying finish his book about a celebrated actor.

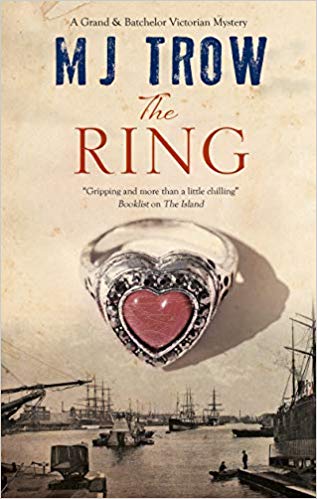

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery:

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery: MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

After an elaborate summing up by Judge James Parke, 1st Baron Wensleydale, (left) the jury retired to consider the precise cause of Belverstone’s death. Not for them days of deliberation, or purdah in some hotel away from the public eye. After a full five minutes, they returned and the foreman stated that George Belverstone had been killed by a blow from Wilson’s fist. The prisoner, at this point, must have had visions of the hangman’s knot swimming before his eyes, but the 1st Baron Wensleydale was minded to differ. Unbelievably, he was of the opinion that although Wilson struck the fatal blow, “the violence was attributed to accident,” and pronounced:

After an elaborate summing up by Judge James Parke, 1st Baron Wensleydale, (left) the jury retired to consider the precise cause of Belverstone’s death. Not for them days of deliberation, or purdah in some hotel away from the public eye. After a full five minutes, they returned and the foreman stated that George Belverstone had been killed by a blow from Wilson’s fist. The prisoner, at this point, must have had visions of the hangman’s knot swimming before his eyes, but the 1st Baron Wensleydale was minded to differ. Unbelievably, he was of the opinion that although Wilson struck the fatal blow, “the violence was attributed to accident,” and pronounced:

Nickson’s latest book introduces a new character, Simon Westow, who walks familiar streets – those of Leeds – but our man is living in Georgian times. England in 1820 was a kingdom of uncertainty. Poor, mad King George was dead, succeeded by his fat and feckless son, the fourth George. Veterans of the war against Napoleon, like many others in later years, found that their homeland was not a land fit for heroes. The Cato Street conspirators, having failed to assassinate the Cabinet, were executed.

Nickson’s latest book introduces a new character, Simon Westow, who walks familiar streets – those of Leeds – but our man is living in Georgian times. England in 1820 was a kingdom of uncertainty. Poor, mad King George was dead, succeeded by his fat and feckless son, the fourth George. Veterans of the war against Napoleon, like many others in later years, found that their homeland was not a land fit for heroes. The Cato Street conspirators, having failed to assassinate the Cabinet, were executed.

With that grim discovery acting as a starting pistol, debut author Robert Scragg (left) starts a middle-distance race to discover who murdered Natasha Barclay. For she is the person, identified by simply reading the opened mail strewn around the tomb-like flat, and checking rental records, whose hand lies in the freezer drawer.

With that grim discovery acting as a starting pistol, debut author Robert Scragg (left) starts a middle-distance race to discover who murdered Natasha Barclay. For she is the person, identified by simply reading the opened mail strewn around the tomb-like flat, and checking rental records, whose hand lies in the freezer drawer. If ever there were an single implausible plot device, it might be the premise that a suburban London flat, complete with a severed hand sitting quietly in a freezer compartment, could remain untouched, unvisited and unnoticed for over thirty years. It is, however, a tribute to Robert Scragg’s skill as a storyteller that this oddity was so easily forgotten. The dialogue, the twists and turns of the plot, and the absolute credibility of the characters swept me along on the ride. Porter and Styles have made an impressive debut, and the author may well have elbowed them into that crowded room full of other fictional police partners. They are all out there; Bryant & May, Zigic & Ferrera, Rizzoli & Isles, Wolfe & Goodwin, Morse & Lewis, Jordan & Hill, Kiszka and Kershaw – watch out, you have company!

If ever there were an single implausible plot device, it might be the premise that a suburban London flat, complete with a severed hand sitting quietly in a freezer compartment, could remain untouched, unvisited and unnoticed for over thirty years. It is, however, a tribute to Robert Scragg’s skill as a storyteller that this oddity was so easily forgotten. The dialogue, the twists and turns of the plot, and the absolute credibility of the characters swept me along on the ride. Porter and Styles have made an impressive debut, and the author may well have elbowed them into that crowded room full of other fictional police partners. They are all out there; Bryant & May, Zigic & Ferrera, Rizzoli & Isles, Wolfe & Goodwin, Morse & Lewis, Jordan & Hill, Kiszka and Kershaw – watch out, you have company!

Dublin copper DI Tom Reynolds is summoned from the dubious delights of his family Christmas to solve a murder. Readers of the previous three Tom Reynolds books might think there is little remarkable about that, but this time the corpse has been in the ground for rather longer than usual. Forty years, in fact. On the island of Oileán na Caillte, the pathologists have been disinterring corpses from a mass grave of the unfortunates who passed away as patients of the long-defunct psychiatric institution, St Christina’s. Those involved in the grim task discover nothing illegal, as all the residents of the burial pit were laid to rest in body bags, tagged and entered onto the hospital records. With one exception. That exception is the corpse of one of St Christina’s medical staff Dr Conrad Howe, who mysteriously disappeared forty Christmases ago. No body bag or tag for Dr Howe, but a rather surreptitious last resting place wedged between two other corpses.

Dublin copper DI Tom Reynolds is summoned from the dubious delights of his family Christmas to solve a murder. Readers of the previous three Tom Reynolds books might think there is little remarkable about that, but this time the corpse has been in the ground for rather longer than usual. Forty years, in fact. On the island of Oileán na Caillte, the pathologists have been disinterring corpses from a mass grave of the unfortunates who passed away as patients of the long-defunct psychiatric institution, St Christina’s. Those involved in the grim task discover nothing illegal, as all the residents of the burial pit were laid to rest in body bags, tagged and entered onto the hospital records. With one exception. That exception is the corpse of one of St Christina’s medical staff Dr Conrad Howe, who mysteriously disappeared forty Christmases ago. No body bag or tag for Dr Howe, but a rather surreptitious last resting place wedged between two other corpses. Other than that dark angel, the cast of suspects includes another former physician, now himself just days away from death, and others whose culpability in the inhuman treatment of St Christina’s patients has left psychological scars, some of which have become dangerously infected. Of course, this being, among other things, a brilliant whodunnit, Jo Spain (right) allows Tom Reynolds – and us readers – to make one major assumption. She then takes great pleasure, the deviously scheming soul that she is, in waiting until the final few pages before turning that assumption not so much on its head as making it do a bloody great cartwheel.

Other than that dark angel, the cast of suspects includes another former physician, now himself just days away from death, and others whose culpability in the inhuman treatment of St Christina’s patients has left psychological scars, some of which have become dangerously infected. Of course, this being, among other things, a brilliant whodunnit, Jo Spain (right) allows Tom Reynolds – and us readers – to make one major assumption. She then takes great pleasure, the deviously scheming soul that she is, in waiting until the final few pages before turning that assumption not so much on its head as making it do a bloody great cartwheel.

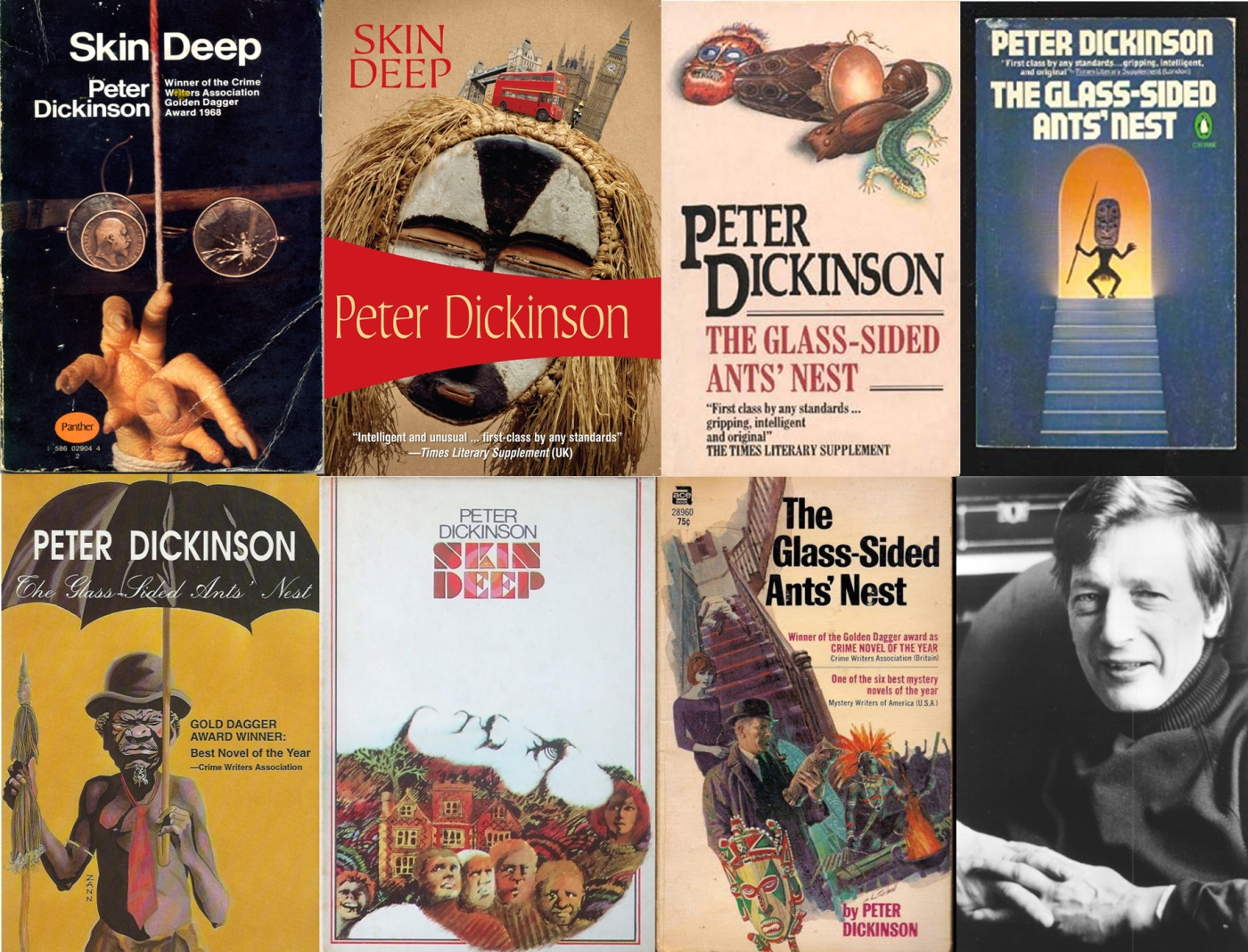

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir