I have always had a morbid fascination with canals. There is something sinister about the unnatural way they snake into towns and cities, often hidden between and beneath buildings. The water is always murky and impenetrable; it could be three feet deep, it could be ten feet deep; the latter is, of course unlikely, but the awful possibility remains. I associate canals with death. Dead bodies. People who have had enough. Rivers are capricious things. They flow, they run shallow, they run deep; they are unreliable. But the canal is different. For someone contemplating what is surely the most awful method of suicide, drowning, the canal offers stillness and silence. The canal will be unlovely, unvisited, and a place where the past hangs heavy. For a killer, wishing to dispose of a body, the same attractions apply. Even as I write, an urban legend grows in strength. People believe The Manchester Pusher is a serial killer (click the link to read the story) who haunts the cold, bleak and dark canal network that runs through the city. There are few lights along the canal towpaths. There is no-one to hear you when you scream. Figures from the Manchester City Area coroner’s office show there have in fact been 35 drownings over the past decade. Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service (GMFRS) say there have been 22 such deaths in the city centre since 2009.

Wisbech had a canal. It was dug out of the Fenland soil in the dying years of the 18th century, and was relatively short, but connected the tidal River Nene with the Great Ouse and was, in its prime, a way to transporting the valuable fruit and vegetable produce of the Fens to the coast, and then onward to other markets. In 1853, the canal remained a viable thoroughfare for farmers. merchants and traders. It was also still enough, cold enough and deep enough to embrace human bodies in its watery arms.

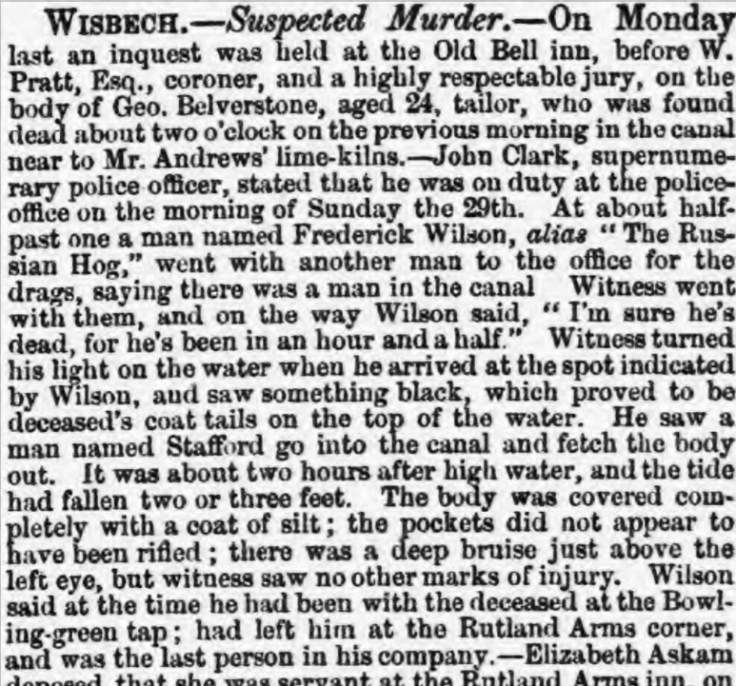

In the grey dawn light of May 29th 1853, a body was found floating in the canal. A witness at the subsequent court case stated:

“I heard someone shout, “There’s a man in the water.” I did not get up until I heard someone say, “It’s young Belverstone!” I knew Belverstone well. I knew Wilson by his nickname ‘The Russian Hog’, but I was not well acquainted with him. I had been brought up with Belverstone from a child. When I heard the cry that he was in the water, I went downstairs and went to the canal side. I then saw Wilson, with several other people. The body was out of the water, and on the bank. I asked Wilson to let me see the body, but he refused. When I asked him who it was, he said, ‘Young Belverstone.’ I asked to see his face, but Wilson said, ‘No – you are a female, and don’t want to see him. When I afterwards saw the body, it was young Belverstone.”

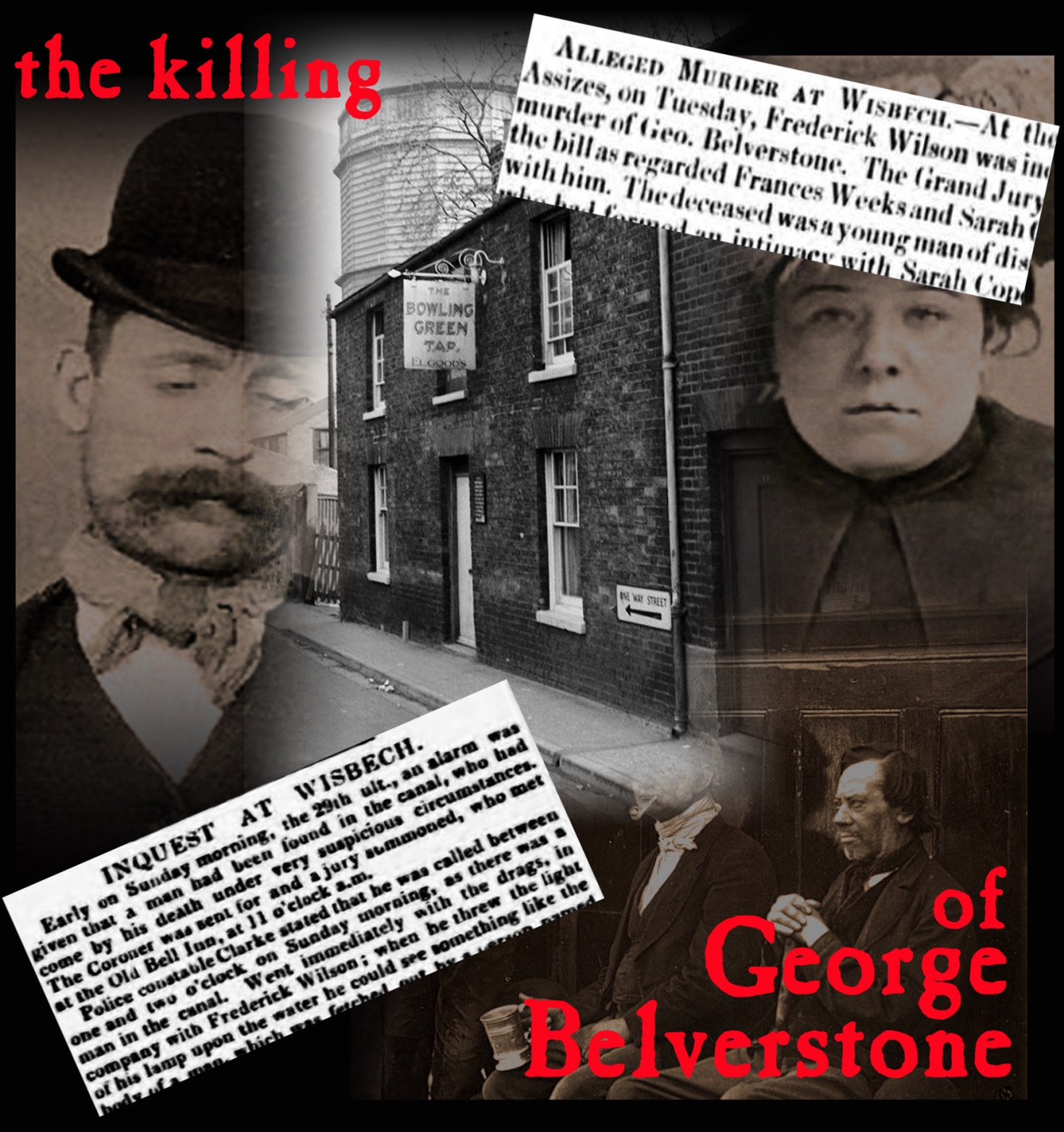

Frederick Wilson, as his nickname might suggest, was a fearsome local brawler. Built like a heavyweight, he held court in several Wisbech pubs. Belverstone, (24) was not unused to pub life, as his father, William, was landlord of another local tavern, The Wheatsheaf.

It seems young George had been drawn to Wilson’s circle of hard characters and female hangers-on, but they saw him as gullible and a prime target for jibes and jokes at his expense. Again, another witness statement from Wilson’s trial for murder:

“At about one o’clock, I was in bed, but woken up. I thought the noise was in our yard. People were laughing, larking and scuffling about in the lane. I went to the window to look. There was a gas lamp in the lane, fifteen or twenty yards from where I was looking. I saw the prisoner and Belverstone, and two women. I didn’t know the women. I saw Belverstone knocked up against Mr Oldham’s door by Wilson and the two women. They did not appear to be angry, but seemed to be all larking. I then saw young Belverstone knocked down on the ground several times. I don’t mean knocked down with fists, I couldn’t see that. They all kept about him larking. He was pushed down three or four times, and then they helped to pick him up, as far as I could see. One of them kept saying, ‘Pick him up, pick him up!’ I don’t know that he was drunk. Once, when he was knocked up against the door he cried out. I saw Wilson strike Belverstone once or twice, but whether by the fist or the back of the hand I cannot say.”

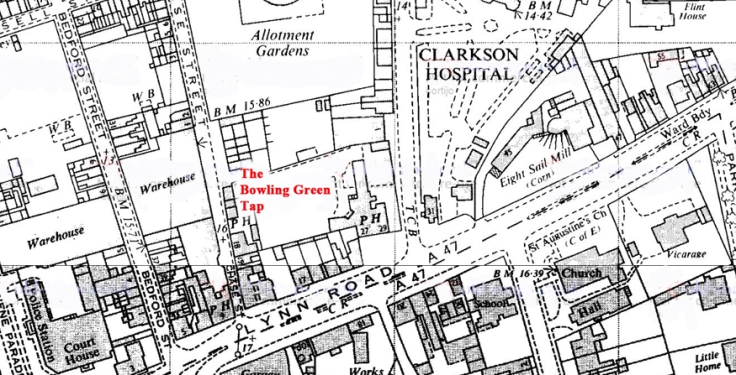

Belverstone’s fatal final evening had been spent in a back street pub called The Bowling Green Tap. It was demolished in the 1970s, but local people still recollect it fondly:

Back in May 1853, it seems that the hapless young Belverstone had supped well but not wisely. He had chosen the company of people who sought entertainment through his vulnerability. In court, the evening’s merrymaking at The Bowling Green Tap was described thus:

“I left about six persons in the house. Belverstone was drinking, and was not sober. He was so tipsy that he fell off his chair, but did not hurt himself.” Mr Power asked, “How would you know?” Mallet replied, “I fancy he didn’t.” The judge asked, “Was he so tipsy that he couldn’t sit on his chair?” Mallet said, “Oh he could sit very well, and he was laughing to see another man so drunk that he fell down.” Mr Power then stated, “Ah, so one man was so drunk that he laughed so much at another drunken man that he could not retain his seat!” Mallet said, “Yes, but there was no quarreling when I was there.”

It seems that Belverstone was struck down by Wilson, who was clearly acting up to impress his female entourage. Somehow Belverstone ended up in the canal. Wilson was arrested and detained on suspicion of murder. His trial was held during the Cambridgeshire Summer Assizes in the July of 1853. There were two key questions which needed answers; Did Belverstone drown, or was he killed by a blow from Wilson? How did he come to be in the canal?

The local surgeon who carried out the post mortem on Belverstone provided an unequivocal answer to one of the questions. He said that the dead man had received a violent blow to the skull, just behind the ear, but saw nothing to indicate death by drowning. As for how Belverstone found his way into the canal, a prisoner called Peter Brett who talked to Wilson while he was on remand seemed to solve the mystery.

“I have known Wilson for two years. I am a prisoner from Wisbech. I met Wilson in prison. He asked me how long I had to stop. I said I was in for a month, and asked him what he was in for, and he said, ‘murder’. He said no more that day, but I saw him a few days after (the 5th of June) and he said, ‘ I have thrown a man into the river.’ I asked him what man, and he replied, ‘George Belverstone.’’’

After an elaborate summing up by Judge James Parke, 1st Baron Wensleydale, (left) the jury retired to consider the precise cause of Belverstone’s death. Not for them days of deliberation, or purdah in some hotel away from the public eye. After a full five minutes, they returned and the foreman stated that George Belverstone had been killed by a blow from Wilson’s fist. The prisoner, at this point, must have had visions of the hangman’s knot swimming before his eyes, but the 1st Baron Wensleydale was minded to differ. Unbelievably, he was of the opinion that although Wilson struck the fatal blow, “the violence was attributed to accident,” and pronounced:

After an elaborate summing up by Judge James Parke, 1st Baron Wensleydale, (left) the jury retired to consider the precise cause of Belverstone’s death. Not for them days of deliberation, or purdah in some hotel away from the public eye. After a full five minutes, they returned and the foreman stated that George Belverstone had been killed by a blow from Wilson’s fist. The prisoner, at this point, must have had visions of the hangman’s knot swimming before his eyes, but the 1st Baron Wensleydale was minded to differ. Unbelievably, he was of the opinion that although Wilson struck the fatal blow, “the violence was attributed to accident,” and pronounced:

“Frederick Wilson, I quite approve of the verdict of the Jury. You have aggravated your offence by adding the guilt of falsehood to your crime of having deprived a fellow creature of life whilst in state of intoxication; I punish you now only for the blow inflicted ; It does not appear that you were in state of anger at all, and there are other mitigating circumstances in your case. I therefore sentence you six months’ imprisonment, with hard labour.”

Six months in jail for killing a man? I believe that those who rail against what they see as the soft sentences handed out to modern criminals should study legal history. The law is, always was, and ever will be – an ass.

My thanks to the members of the Facebook group Wisbech Pictures Old and New, particularly the family of the late Geoff Hastings, Andy Ketley, Roger Rawson, Steve Williams, Andy Ward, Patricia Warden and Pat Prewer for their photographs and memories.

February 21, 2021 at 4:16 pm

I have just found this online and it is completely fascinating to me. The reason being George Belverstone was my 2x Great Uncle. (His sister Elizabeth Mckenzie(nee Belverstone being my Great Grandma). Thank you for posting on line.

LikeLiked by 1 person

February 21, 2021 at 6:51 pm

A sad story. I can’t help thinking his killer got off lightly. There are still local people who remember drinking in The Bowling Green Tap.

LikeLike