London in 1967 seems to have been an exciting place to live. A play by a budding writer called Alan Aykbourne received its West End premier, Jimi Hendrix was setting fire to perfectly serviceable Fender Strats, The House of Commons passed the Sexual Offences Act decriminalising male homosexuality and Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell featured in a murder-suicide in their Islington flat. This is the backdrop as Hugh Fraser’s violent anti-heroine Rina Walker returns to her murderous ways in Stealth, the fourth novel of a successful series.

London in 1967 seems to have been an exciting place to live. A play by a budding writer called Alan Aykbourne received its West End premier, Jimi Hendrix was setting fire to perfectly serviceable Fender Strats, The House of Commons passed the Sexual Offences Act decriminalising male homosexuality and Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell featured in a murder-suicide in their Islington flat. This is the backdrop as Hugh Fraser’s violent anti-heroine Rina Walker returns to her murderous ways in Stealth, the fourth novel of a successful series.

I am new to Ms Walker’s world, but soon learned that a brutal childhood deep in poverty, where attack was frequently the best form of defence, and a later upbringing embedded in the world of London gangsters, has shaped her view of life. Although parliament had decreed that chaps could sleep with chaps, provided both were willing, there was little public approval for chapesses having the same latitude, and so Rina’s love affair with girlfriend Lizzie is accepted but not flaunted.

Lizzie has been set up by Rina as proprietor of a Soho club, more or less legit, but with a multitude of blind eyes which fail to focus on minor breaches of the moral code. When a young tart is found in a club back room, battered to death with a hammer, Rina not only takes offence but wreaks summary revenge. The killer, a bare-knuckle fighter called Dave Priest, is not only thumped by his latest opponent on the cobblestoned back yard of a dingy pub, but becomes the latest victim of what might be called Rina’s Law when she kills him and artfully arranges his corpse to look as if he had slipped on the stairs.

Rina is locked into a world where she is forever repaying favours, or earning them and taking rain checks for a later day. One of her debts is to a grim and sordid gang boss who, in turn, owes a favour to a homicidal maniac currently a patient in Broadmoor. This particular penance involves her bumping off a perfectly innocent builder who has had the temerity to offer the maniac’s wife a new life in the dreamy suburbs of Romford. Rina is not totally without moral scruples, although if you blink you will miss them as they whizz past your eye line at the speed of light. She tries to scam her employer by staging the death of the honest builder, but she is found out in a complex sting involving shadowy operatives of military intelligence.

Is Rina fazed by the step-up in class from bumping off Essex builders to the complex world of international intrigue, Cold War deception and men in expensive suits who never, ever are who they say they are? No, not for one moment. Whether downing large whiskies in backstreet pubs, or sipping chateau-bottled claret in expensive hotel suites, our Rina is equal to the task, be it on home turf or in the romantically sleazy cafes and bars of Istanbul.

The list of fine actors who have turned their hand to crime fiction is extremely short, not to say minuscule. Even more invisible, except via an electron microscope, is the catalogue of crime writing actors who play languid toffs. I yield to no-one in my admiration for Hugh Fraser in his roles as Captain Hastings and – my absolute favourite – his insouciant Duke of Wellington in Sharpe. The difference between Fraser’s screen persona and the world of Rina Walker could not be more extreme.

To cut to the chase, does Stealth work? It does, and triumphantly so. Fraser might be just a tad too young to have experienced the Soho of the mid 1960s, but if the scene setting isn’t from personal recollection, he has certainly done his homework. My only slight criticism is that I found that the constant mood/time/product placement via contemporary pop song titles began to grate after a while. There is a touch of “with one bound she was free” about Rina Walker, and you would certainly think twice about taking her home to meet mummy and daddy in Virginia Water, but under the capable direction of Hugh Fraser her adventures provide an enjoyably violent and escapist crime read. Stealth is out on 8th October and is brought to us by Urbane Publications.

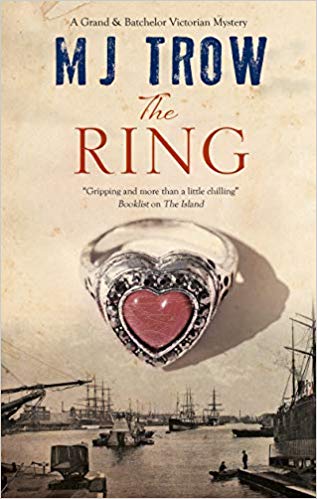

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery:

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery: MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

With that grim discovery acting as a starting pistol, debut author Robert Scragg (left) starts a middle-distance race to discover who murdered Natasha Barclay. For she is the person, identified by simply reading the opened mail strewn around the tomb-like flat, and checking rental records, whose hand lies in the freezer drawer.

With that grim discovery acting as a starting pistol, debut author Robert Scragg (left) starts a middle-distance race to discover who murdered Natasha Barclay. For she is the person, identified by simply reading the opened mail strewn around the tomb-like flat, and checking rental records, whose hand lies in the freezer drawer. If ever there were an single implausible plot device, it might be the premise that a suburban London flat, complete with a severed hand sitting quietly in a freezer compartment, could remain untouched, unvisited and unnoticed for over thirty years. It is, however, a tribute to Robert Scragg’s skill as a storyteller that this oddity was so easily forgotten. The dialogue, the twists and turns of the plot, and the absolute credibility of the characters swept me along on the ride. Porter and Styles have made an impressive debut, and the author may well have elbowed them into that crowded room full of other fictional police partners. They are all out there; Bryant & May, Zigic & Ferrera, Rizzoli & Isles, Wolfe & Goodwin, Morse & Lewis, Jordan & Hill, Kiszka and Kershaw – watch out, you have company!

If ever there were an single implausible plot device, it might be the premise that a suburban London flat, complete with a severed hand sitting quietly in a freezer compartment, could remain untouched, unvisited and unnoticed for over thirty years. It is, however, a tribute to Robert Scragg’s skill as a storyteller that this oddity was so easily forgotten. The dialogue, the twists and turns of the plot, and the absolute credibility of the characters swept me along on the ride. Porter and Styles have made an impressive debut, and the author may well have elbowed them into that crowded room full of other fictional police partners. They are all out there; Bryant & May, Zigic & Ferrera, Rizzoli & Isles, Wolfe & Goodwin, Morse & Lewis, Jordan & Hill, Kiszka and Kershaw – watch out, you have company!

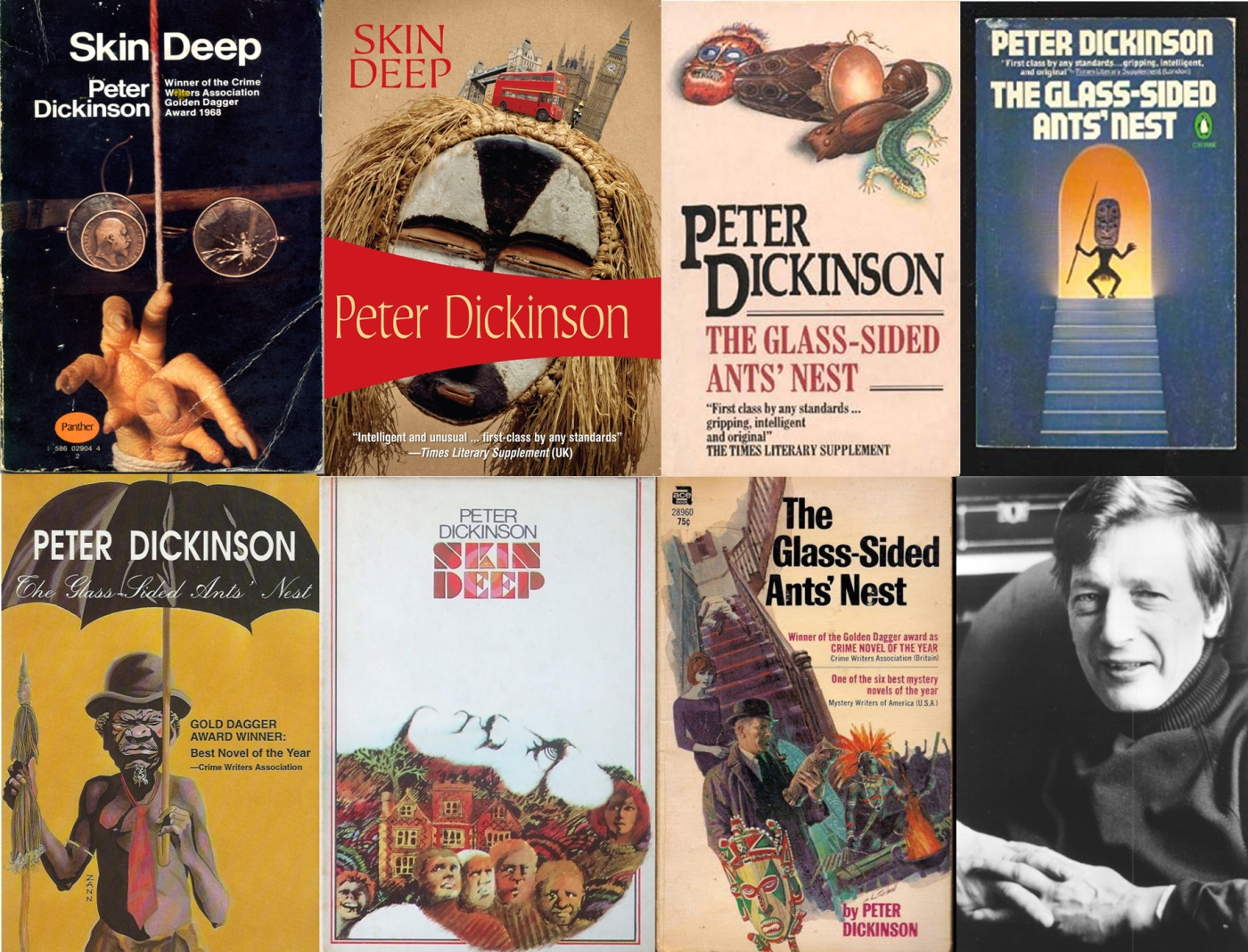

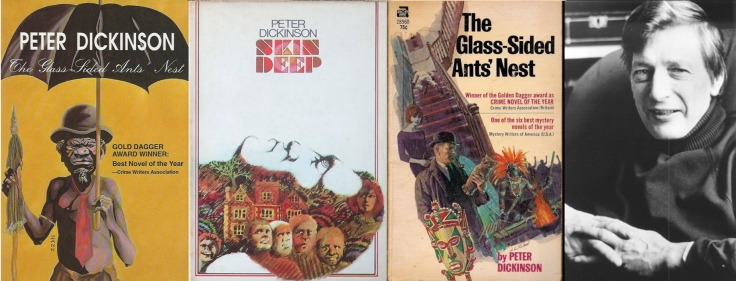

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson.

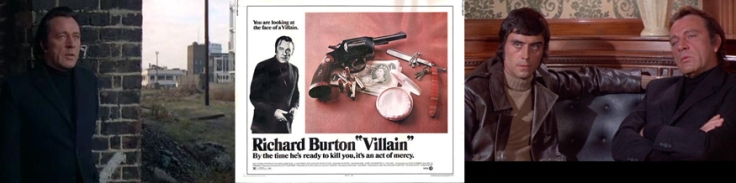

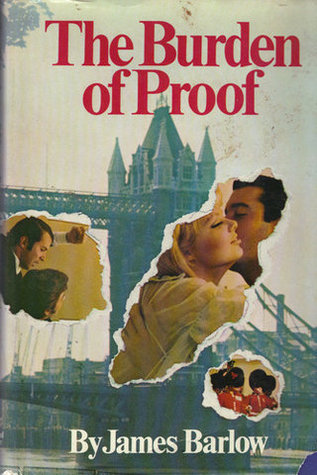

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson. Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

This is a curious and quite unsettling book which does not fit comfortably into any crime fiction pigeon-hole. I don’t want to burden it with a flattering comparison with which other readers may disagree, but it did remind me of John Fowles’s intriguing and mystifying cult novel from the 1960s, The Magus. I am showing my age here and, OK, The Gilded Ones is about a quarter of the length of The Magus, it’s set in 1980s London rather than a Greek island and the needle on the Hanky Panky Meter barely flickers. However we do have a slightly ingenuous central character who serves a charismatic, powerful and magisterial master and there is a nagging sense that, as readers, we are having the wool pulled over our eyes. There is also an uneasy feeling of dislocated reality and powerful sensory squeezes, particularly of sound and smell. Author Brooke Fieldhouse (left) even gives us female twins who are not, sadly, as desirable as Lily and Rose de Seitas in the Fowles novel.

This is a curious and quite unsettling book which does not fit comfortably into any crime fiction pigeon-hole. I don’t want to burden it with a flattering comparison with which other readers may disagree, but it did remind me of John Fowles’s intriguing and mystifying cult novel from the 1960s, The Magus. I am showing my age here and, OK, The Gilded Ones is about a quarter of the length of The Magus, it’s set in 1980s London rather than a Greek island and the needle on the Hanky Panky Meter barely flickers. However we do have a slightly ingenuous central character who serves a charismatic, powerful and magisterial master and there is a nagging sense that, as readers, we are having the wool pulled over our eyes. There is also an uneasy feeling of dislocated reality and powerful sensory squeezes, particularly of sound and smell. Author Brooke Fieldhouse (left) even gives us female twins who are not, sadly, as desirable as Lily and Rose de Seitas in the Fowles novel. Lloyd Lewis is the Magus-like figure. He is so thumpingly male that you can almost smell him, and he rules those around him, with one exception, with an almost feral ferocity. So who are ‘those around him’? Ever present psychologically, but eternally absent physically, is his late wife Freia, the subject of Pulse’s dream. Martinique is Patrick’s girlfriend, and loitering in the background are his children, step-child and office gofer Lauren. Lauren, who has “thousand-year-old eyes”, is of the English nobility, but quite what she is doing in the Georgian townhouse we only learn at the end of the book. The one person to whom Patrick defers is his Sicilian friend Falco. Equalling the Englishman’s sense of menace, the sinister Falco appears briefly but is, nonetheless, memorable.

Lloyd Lewis is the Magus-like figure. He is so thumpingly male that you can almost smell him, and he rules those around him, with one exception, with an almost feral ferocity. So who are ‘those around him’? Ever present psychologically, but eternally absent physically, is his late wife Freia, the subject of Pulse’s dream. Martinique is Patrick’s girlfriend, and loitering in the background are his children, step-child and office gofer Lauren. Lauren, who has “thousand-year-old eyes”, is of the English nobility, but quite what she is doing in the Georgian townhouse we only learn at the end of the book. The one person to whom Patrick defers is his Sicilian friend Falco. Equalling the Englishman’s sense of menace, the sinister Falco appears briefly but is, nonetheless, memorable.

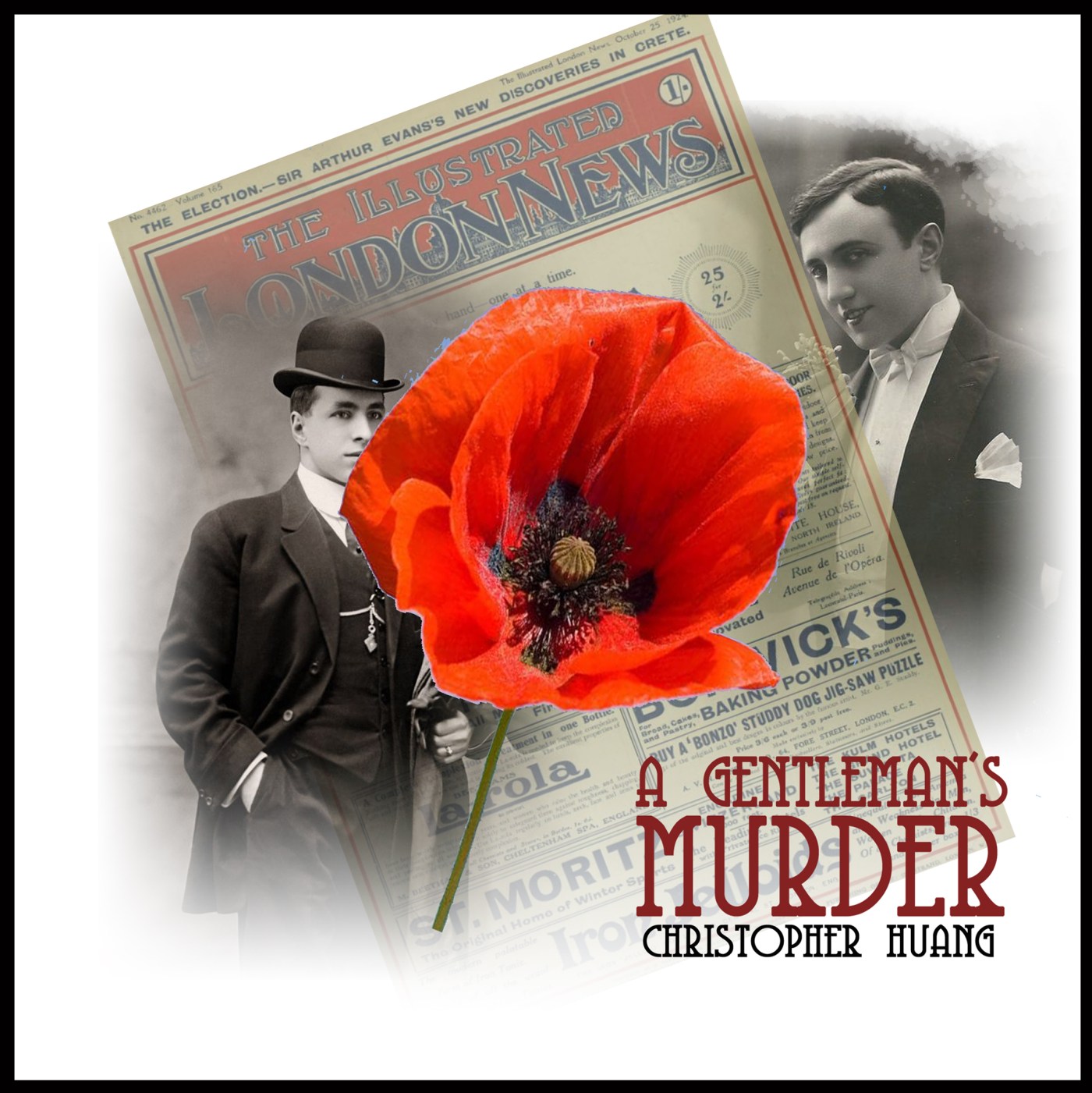

Eric Peterkin is one such and, although he carries his rank with pride, he is just a little different, and he is viewed with some disdain by certain fellow members and simply tolerated by others. Despite generations of military Peterkins looking down from their portraits in the club rooms, Eric is what is known, in the language of the time, a half-caste. His Chinese mother has bequeathed him more than enough of the characteristics of her race for the jibe, “I suppose you served in the Chinese Labour Corps?” to become commonplace.

Eric Peterkin is one such and, although he carries his rank with pride, he is just a little different, and he is viewed with some disdain by certain fellow members and simply tolerated by others. Despite generations of military Peterkins looking down from their portraits in the club rooms, Eric is what is known, in the language of the time, a half-caste. His Chinese mother has bequeathed him more than enough of the characteristics of her race for the jibe, “I suppose you served in the Chinese Labour Corps?” to become commonplace. Christopher Huang (right) was born and raised in Singapore where he served his two years of National Service as an Army Signaller. He moved to Canada where he studied Architecture at McGill University in Montreal. Huang currently lives in Montreal.. Judging by this, his debut novel, he also knows how to tell a story. He gives us a fascinating cast of gentleman club members, each of them worked into the narrative as a murder suspect. We have Mortimer Wolfe – “sleek, dapper and elegant, hair slicked down and gleaming like mahogany”, club President Edward Aldershott, “Tall, prematurely grey and with a habit of standing perfectly still …like a bespectacled stone lion,” and poor, haunted Patrick “Patch” Norris with his constant, desperate gaiety.

Christopher Huang (right) was born and raised in Singapore where he served his two years of National Service as an Army Signaller. He moved to Canada where he studied Architecture at McGill University in Montreal. Huang currently lives in Montreal.. Judging by this, his debut novel, he also knows how to tell a story. He gives us a fascinating cast of gentleman club members, each of them worked into the narrative as a murder suspect. We have Mortimer Wolfe – “sleek, dapper and elegant, hair slicked down and gleaming like mahogany”, club President Edward Aldershott, “Tall, prematurely grey and with a habit of standing perfectly still …like a bespectacled stone lion,” and poor, haunted Patrick “Patch” Norris with his constant, desperate gaiety.

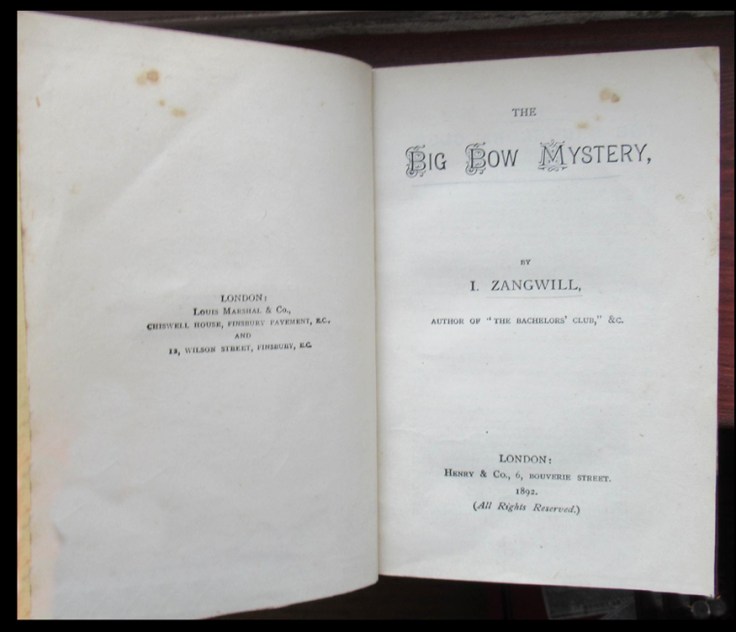

The ‘Bow’ in the title is not some fabric adornment, but the working class district in East London. If you were born within earshot of its church bells, then you were said to be a true Cockney. It’s December, and the nineteenth century is on its last legs. A dense morning fog, aided and abetted by the smoke of a million coal fires, swirls around the mean streets.

The ‘Bow’ in the title is not some fabric adornment, but the working class district in East London. If you were born within earshot of its church bells, then you were said to be a true Cockney. It’s December, and the nineteenth century is on its last legs. A dense morning fog, aided and abetted by the smoke of a million coal fires, swirls around the mean streets. The formidable lady has overslept, but after lighting the downstairs fire, she remembers to wake one of the lodgers. Arthur Constant is an idealist, and a campaigner for workers’ rights. She bangs on his bedroom door, then makes the day’s first pot of tea. Taking a tray upstairs, she calls again. Still no response. She peeps through the keyhole, but the key is firmly in place. As she pounds on the door once again, she has a premonition that something is very, very wrong. So she summons her neighbour, the redoubtable retired detective Mr George Grodman. He batters down the door, which was locked and bolted from the inside, and is forced to cover Mrs Drabdump’s eyes from the horrors within…

The formidable lady has overslept, but after lighting the downstairs fire, she remembers to wake one of the lodgers. Arthur Constant is an idealist, and a campaigner for workers’ rights. She bangs on his bedroom door, then makes the day’s first pot of tea. Taking a tray upstairs, she calls again. Still no response. She peeps through the keyhole, but the key is firmly in place. As she pounds on the door once again, she has a premonition that something is very, very wrong. So she summons her neighbour, the redoubtable retired detective Mr George Grodman. He batters down the door, which was locked and bolted from the inside, and is forced to cover Mrs Drabdump’s eyes from the horrors within… Some contemporary critics were puzzled and irritated by Zangwill’s satirical style. They felt that there was no place for comedy in the tale of a young man, dead in his bed, his throat cut from ear to ear. The exchanges in the court scenes between pompous officials and outspoken ‘low life’ types on the jury are delightfully reminiscent of similar encounters between Mr Pooter and disrespectful tradesmen in that classic of English humour, The Diary of A Nobody.

Some contemporary critics were puzzled and irritated by Zangwill’s satirical style. They felt that there was no place for comedy in the tale of a young man, dead in his bed, his throat cut from ear to ear. The exchanges in the court scenes between pompous officials and outspoken ‘low life’ types on the jury are delightfully reminiscent of similar encounters between Mr Pooter and disrespectful tradesmen in that classic of English humour, The Diary of A Nobody.