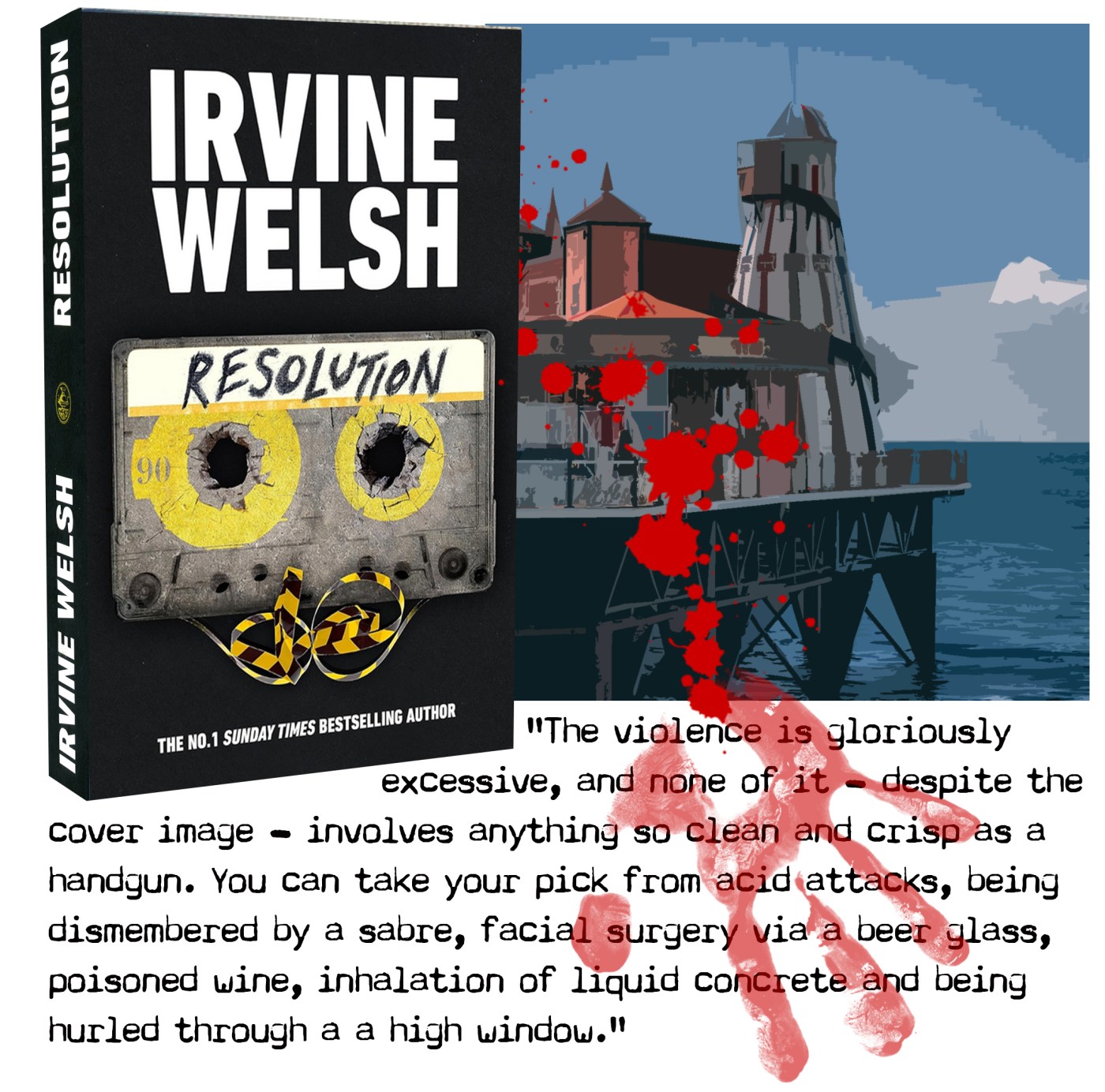

Edinburgh copper Ray Lennox last appeared a couple of years ago in The Long Knives. Now, he has quit the force and, given his predilections, is in a strange place on what might be thought foreign soil – England’s south coast, a partner in a security firm based in Horsham, with his customer base ranging from the gay green madness of Brighton, to the villas of Eastbourne, where the silence is only punctuated by the quiet hum of wheelchair tyres and the creak of zimmer frames.

His business partner is George Marsden, in some ways the antithesis of Lennox, in that he is English public school, suave, urbane, and speaks the esoteric language of the English middle classes. He is no man’s dupe, however, as we are given hints that he once served with the Special Boat Service.

Lennox is deeply in lust with a local chemistry lecturer, Carmel Devereux, some years his junior, and it is at a meet and greet party with potential wealthy sponsors of her research, that he is staggered to see the face of Mathew Cardingworth, a character from wounding nightmares. In an Edinburgh underpass, all those years ago, Cardingworth was one of a gang that captured Lennox and his teenage mate Les Brodie, and subjected them to grim sexual and physical abuse.

Fantasising about getting even with Cardingworth, Lennox actually meets him socially and then makes the error of accepting Cardingworth’s offer of a couple of tickets for the executive box at Brighton’s next Premiership home game against Liverpool. An even worse mistake is inviting Les Brodie down from Scotland, standing him the air fare as a treat. Whereas Lennox’s vengeance against his abuser have stayed firmly inside his head, Les Brodie is more volatile. He catches sight of Cardingworth as they drink their pints and graze at the buffet; it only takes seconds for Brodie to recognise his abuser, and he is just as quick to smash his glass on the bar counter and thrust it into Cardingworth’a face.

As his obsession with Cardingworth deepens, Lennox discovers that there is a tenuous – but intriguing link between the businessman and several youngsters who disappeared from the ‘care’ of Sussex Children’s Services. The fact that all local and national newspaper references to those years – print, microfiche and digital – have all disappeared. In another puzzle, at least for the reader, one of the non-Brighton, non-now narratives in the book is in the voice of an Englishman, perhaps a merchant seaman, who has killed a man in a Shanghai bar fight and been incarcerated sine die in a vile Chinese prison. He is clearly a deeply damaged and dangerous man, and he appears to be directing his story at Lennox, but who is he?

Lennox, as he peels back the layers of the recent past, all too late realises he is in way over his head, but with almost suicidal and terrier-like tenacity, he presses on regardless, perhaps echoing the thoughts of his famous fictional countryman, who mused:

“I am in blood

Stepped in so far, that, should I wade no more,

Returning were as tedious as go o’er”

Fans of Welsh will love this, and feel at home with how the story darts back and forth between various characters, the Scottish conversational vernacular, the violence, the sex – and the grim humour. There is one wonderful example of the latter when contractors installing a new security system in a retirement home fall foul of a particularly demented resident, and all hell breaks loose. The titular resolution does not happen until the final pages of the book and it occurs, ironically, in the same care home where the contractors came so comically to grief. The violence is gloriously excessive, and none of it – despite the cover image – involves anything so clean and crisp as a handgun. You can take your pick from acid attacks, being dismembered by a sabre, facial surgery via a beer glass, poisoned wine, inhalation of liquid concrete and being hurled through a a high window. Resolution is published by Jonathan Cape and will be out on 11th July.

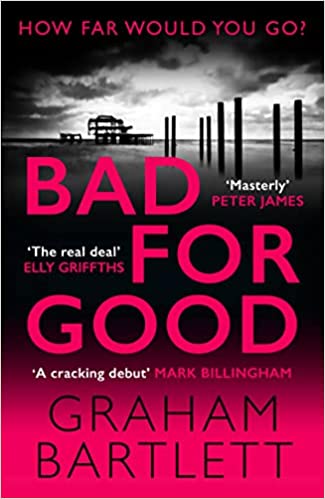

The plot hinges around a series of dire events in the life of Jo Howe’s boss, Detective Chief Superintendent Phil Cooke. Already trying to keep his mind on the job while his wife is dying of cancer, fate deals him another cruel blow when his son Harry, a promising professional footballer, is murdered, seemingly a casualty in a drug turf war. He steps down, but then comes into contact with a shadowy group of apparent vigilantes, who tell him that Harry was not the clean-cut sporting hero portrayed in the local media – he was heavily into performance enhancing drugs. The vigilantes – whose business plan is to provide a highly illegal alternative police force, where customers pay for the quick results that the Sussex Constabulary seem unable to provide – blackmail Phil into standing in the election of Police and Crime Commissioner. He is forced to agree, and is elected.

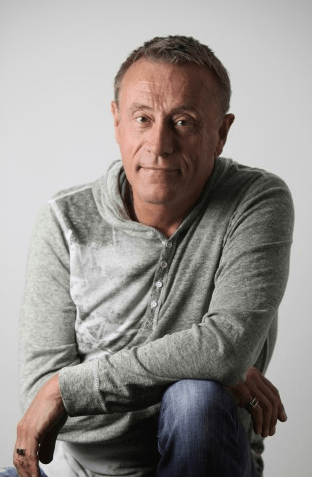

The plot hinges around a series of dire events in the life of Jo Howe’s boss, Detective Chief Superintendent Phil Cooke. Already trying to keep his mind on the job while his wife is dying of cancer, fate deals him another cruel blow when his son Harry, a promising professional footballer, is murdered, seemingly a casualty in a drug turf war. He steps down, but then comes into contact with a shadowy group of apparent vigilantes, who tell him that Harry was not the clean-cut sporting hero portrayed in the local media – he was heavily into performance enhancing drugs. The vigilantes – whose business plan is to provide a highly illegal alternative police force, where customers pay for the quick results that the Sussex Constabulary seem unable to provide – blackmail Phil into standing in the election of Police and Crime Commissioner. He is forced to agree, and is elected. Graham Bartlett (right) was a police officer for thirty years and mainly policed the city of Brighton and Hove, rising to become a Chief Superintendent and its police commander, so it is no accident that this is a grimly authentic police procedural. It is also very topical as, away from the violence and entertaining mayhem, it focuses on the seemingly insoluble problem of the divide between the public’s expectations of policing, and what the force is actually able – or willing – to deliver. Bartlett doesn’t over-politicise his story but, reading between the lines – and I may be mistaken – I suspect he may feel that, with ever more limited resources, the police should not be so keen to divert valuable time and resources away from their core job of catching criminals. My view. and it may not be his, is that effusive virtue signaling by police forces in support of this or that social justice trend does them – nor most of us – no favours at all.

Graham Bartlett (right) was a police officer for thirty years and mainly policed the city of Brighton and Hove, rising to become a Chief Superintendent and its police commander, so it is no accident that this is a grimly authentic police procedural. It is also very topical as, away from the violence and entertaining mayhem, it focuses on the seemingly insoluble problem of the divide between the public’s expectations of policing, and what the force is actually able – or willing – to deliver. Bartlett doesn’t over-politicise his story but, reading between the lines – and I may be mistaken – I suspect he may feel that, with ever more limited resources, the police should not be so keen to divert valuable time and resources away from their core job of catching criminals. My view. and it may not be his, is that effusive virtue signaling by police forces in support of this or that social justice trend does them – nor most of us – no favours at all.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

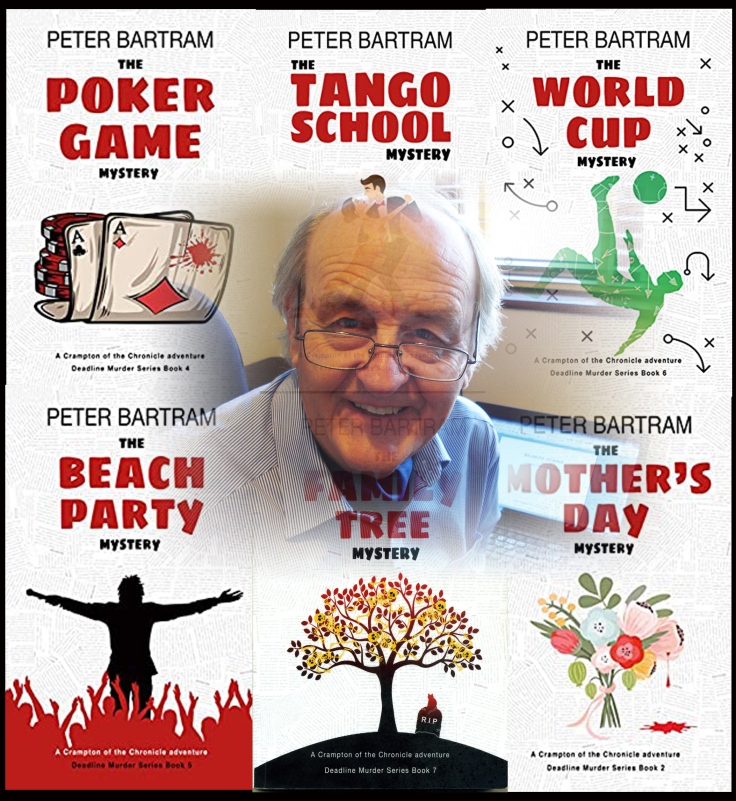

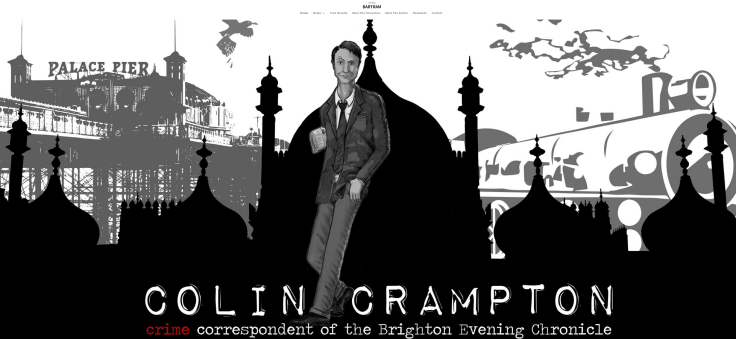

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle. One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master.

One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master. hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her.

hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her. ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly.

ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly. Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

It is 1965 and we are basking in the slightly faded grandeur of Brighton, on the south coast of England. The town has never quite recovered from its association, more than a century earlier, with the bloated decadence of The Prince Regent, and it shrugs its shoulders at the more recent notoriety bestowed by a certain crime novel brought to life on the big screen in 1947. Brighton has its present-day misdeeds too, and who better to write about it than the intrepid crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle, Colin Crampton?

It is 1965 and we are basking in the slightly faded grandeur of Brighton, on the south coast of England. The town has never quite recovered from its association, more than a century earlier, with the bloated decadence of The Prince Regent, and it shrugs its shoulders at the more recent notoriety bestowed by a certain crime novel brought to life on the big screen in 1947. Brighton has its present-day misdeeds too, and who better to write about it than the intrepid crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle, Colin Crampton? rampton is an enterprising and thoroughly likeable fellow, with a rather nice sports car and an even nicer girlfriend, in the very pleasing shape of Australian lass Shirley Goldsmith. Crampton is summoned to the office of his deputy editor Frank Figgis and, barely discernible amid the wreaths of smoke from his Woodbines, Figgis’s face is creased by more worry lines than usual. His problem? The Chronicle’s drama correspondent, Sidney Pinker, has been served with a libel writ for savaging, in print, a local theatrical agent called Daniel Bernstein.

rampton is an enterprising and thoroughly likeable fellow, with a rather nice sports car and an even nicer girlfriend, in the very pleasing shape of Australian lass Shirley Goldsmith. Crampton is summoned to the office of his deputy editor Frank Figgis and, barely discernible amid the wreaths of smoke from his Woodbines, Figgis’s face is creased by more worry lines than usual. His problem? The Chronicle’s drama correspondent, Sidney Pinker, has been served with a libel writ for savaging, in print, a local theatrical agent called Daniel Bernstein.

inker, by the way, is very much in the John Inman school of caricature luvvies, so those with an over-sensitive approach had better look away now. His pale green shirts, flowery cravats and patronage of certain Brighton nightspots are pure (politically incorrect) comedy.

inker, by the way, is very much in the John Inman school of caricature luvvies, so those with an over-sensitive approach had better look away now. His pale green shirts, flowery cravats and patronage of certain Brighton nightspots are pure (politically incorrect) comedy. Bernstein’s murder is seen as very much open-and-shut by the Brighton coppers, but Crampton does not believe that Pinker has the mettle to commit physical violence. Instead, his investigation takes him into the rather sad world of stand-up comedians. Today, our stand-up gagsters can become millionaire celebrities, but back in 1965, the old style joke tellers with their catchphrases and patter were becoming a thing of the past, as TV satire was breaking new ground and reaching new audiences. Crampton believes that the murder of Bernstein is connected to the agent’s former association with Max Miller and, crucially, the possession of Miller’s fabled Blue Book, said to contain all of The Cheeky Chappy’s best material – and a few jokes considered too rude for polite company.

Bernstein’s murder is seen as very much open-and-shut by the Brighton coppers, but Crampton does not believe that Pinker has the mettle to commit physical violence. Instead, his investigation takes him into the rather sad world of stand-up comedians. Today, our stand-up gagsters can become millionaire celebrities, but back in 1965, the old style joke tellers with their catchphrases and patter were becoming a thing of the past, as TV satire was breaking new ground and reaching new audiences. Crampton believes that the murder of Bernstein is connected to the agent’s former association with Max Miller and, crucially, the possession of Miller’s fabled Blue Book, said to contain all of The Cheeky Chappy’s best material – and a few jokes considered too rude for polite company. here have been occasions – and I am not alone – when I have used the term cosy in a book review, meaning no ill-will by it, but perhaps suggesting a certain lack of seriousness or an avoidance of the grim details of crime. Are the Colin Crampton books cosy? Perhaps.You will search in vain for explorations of the dark corners of the human psyche, any traces of bitterness or the consuming powers of grief and anger. What you will find is humour, clever plotting, a warm sense of nostalgia and – above all – an abundance of charm. A dictionary defines that word as “the power or quality of delighting, attracting, or fascinating others.” Remember, though, that the word has another meaning, that of an apparently insignificant trinket, but one which brings the wearer a sense of well-being and even, perhaps, the power to produce something magical.

here have been occasions – and I am not alone – when I have used the term cosy in a book review, meaning no ill-will by it, but perhaps suggesting a certain lack of seriousness or an avoidance of the grim details of crime. Are the Colin Crampton books cosy? Perhaps.You will search in vain for explorations of the dark corners of the human psyche, any traces of bitterness or the consuming powers of grief and anger. What you will find is humour, clever plotting, a warm sense of nostalgia and – above all – an abundance of charm. A dictionary defines that word as “the power or quality of delighting, attracting, or fascinating others.” Remember, though, that the word has another meaning, that of an apparently insignificant trinket, but one which brings the wearer a sense of well-being and even, perhaps, the power to produce something magical.

In The Mother’s Day Mystery, Crampton discovers the body of a schoolboy who has evidently been knocked off his bike and fatally injured. What on earth was Spencer Hooke doing away from his dormitory in Steyning Grammar School at the dead of night, cycling along a lonely and windswept clifftop road? In pursuing this conundrum, Crampton whisks us into a world of stage vicars, seedy pub landlords, archetypal leather-elbowed schoolmasters and impecunious toffs. There are jokes a-plenty, and Bartram indulges himself – and those of us who are, similarly, in the autumn of our years – with many a knowing cultural reference that might puzzle younger readers. He takes us into a wonderful sweet shop, the kind which can nowadays only be found in museum recreations:

In The Mother’s Day Mystery, Crampton discovers the body of a schoolboy who has evidently been knocked off his bike and fatally injured. What on earth was Spencer Hooke doing away from his dormitory in Steyning Grammar School at the dead of night, cycling along a lonely and windswept clifftop road? In pursuing this conundrum, Crampton whisks us into a world of stage vicars, seedy pub landlords, archetypal leather-elbowed schoolmasters and impecunious toffs. There are jokes a-plenty, and Bartram indulges himself – and those of us who are, similarly, in the autumn of our years – with many a knowing cultural reference that might puzzle younger readers. He takes us into a wonderful sweet shop, the kind which can nowadays only be found in museum recreations: Anyone who is a student of English humour will soon see that Bartram is part of a long and distinguished tradition of comic writers who find meat and drink in the absurdities of English life and social structures. In the world of crime fiction, however, comedy does not always sit well with murder and bloodshed. The great and sadly under-appreciated

Anyone who is a student of English humour will soon see that Bartram is part of a long and distinguished tradition of comic writers who find meat and drink in the absurdities of English life and social structures. In the world of crime fiction, however, comedy does not always sit well with murder and bloodshed. The great and sadly under-appreciated