It’s 7.00pm on a Thursday in September 1964 and a goodly proportion of the British population are settling down in front of their television sets to watch one of the most popular shows of the time.

The programme, Double Your Money, starts with a catchy tune that ends with lyrics – “double your money and try to get rich” – that leave no doubt what the show is about. The credit titles fade and a thin man with a cheesy grin, popping eyes, and a faintly transatlantic accent, steps in front of the cameras.

Hughie Green was one of a group of 1960s TV presenters who made their names as game show hosts. By today’s standards, most of the shows seem corny. In Double Your Money, the contestant would answer a question on the subject of their choice – sport and spelling were two favourites – to win £1. If they got it right, they’d move on to a £2, then £4 question all the way up to £32. If they answered that correctly, some had an opportunity to move on to the “Treasure Trail” where they could win up to £1,000 – equivalent to £18,600 in today’s money.

Most of these shows turned up on ITV – commercial television started broadcasting in Britain in 1955 – because the publically-funded BBC didn’t think it right to give away licence-payers’ money in cash prizes. The BBC stuck to more cerebral game shows, like University Challenge, which first broadcast in 1962 and was based on a US television show called College Bowl.

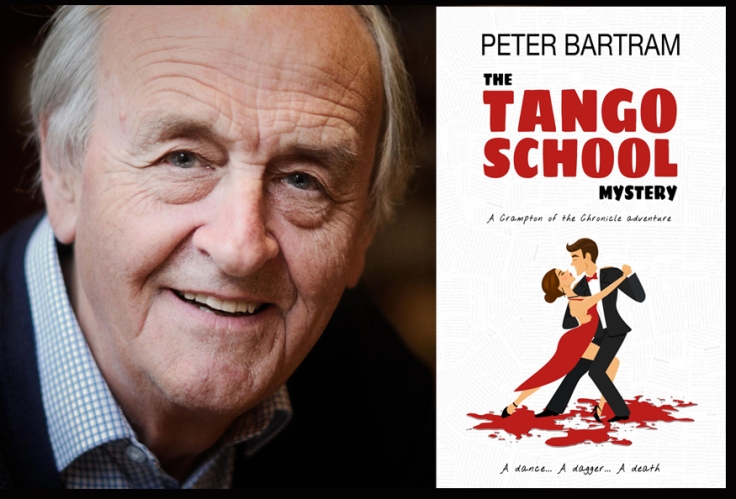

One thing is certain, Colin Crampton, crime reporter on the Brighton Evening Chronicle, and his girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith would not have been among the 15 million people tuning into Double Your Money. They were too busy chasing the killers in The Tango School Mystery.

It meant they would also have missed other top game shows of the time, such as Take Your Pick, hosted by Michael Miles, a character with all the on-screen charm of a second-hand car salesman. A car – definitely not second-hand – would sometimes be the star prize on the show.

To get a shot at winning a prize, contestants had to answer three out of four general knowledge questions. They would then pick the key to one of 10 boxes. Seven contained good prizes, such as a TV set or holiday, while three held booby prizes. Before they got to open the box, Miles would try to buy the key back off the contestant in a kind of reverse Dutch auction. Most players resisted and ended up with whatever the box had to offer.

As the 1960s progressed, TV companies sought more and more inventive formulae for their game shows. Criss Cross Quiz was based on the US show Tic Tac Dough. It was presented first by Jeremy Hawk and then by Barbara Kelly. Two contestants played a game of nought and crosses. Each took turns to answer a question to get a nought or a cross in a square. They won £20 for every square they filled or £40 for the centre square. The winner – the first to get three noughts or crosses in a row – became the champion and took on another challenger.

The Golden Shot involved contestants, either at home on the telephone or an isolation booth in the studio, directing a blindfolded cameraman with a crossbow bolted to his camera. The contestant could see the target on the TV screen and directed the cameraman with instructions like “left a bit”, or “down then stop” et until they’d lined up the target and gave the order to fire.

On one occasion, a contestant took part from a telephone box. He was watching the screen on a television in a shop window. Half way through his directions to the cameraman the shop TV was turned off.

But it wasn’t only big-prize game shows that pulled in viewers during the Swinging Sixties. Panel games, such as What’s My Line and Call My Bluff, were popular, especially with older viewers. But other game shows, such as Concentration, Jokers Wild and Password, are long forgotten. Which only goes to prove that even among game shows there were winners and losers.

Peter Bartram’s new Colin Crampton mystery is out now, and a full review of the book will be on here very shortly!

Leave a comment