PART TWO

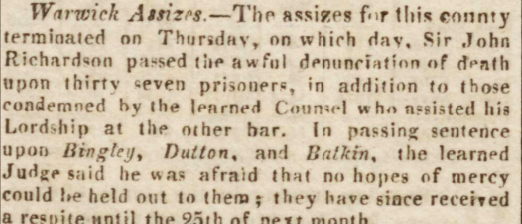

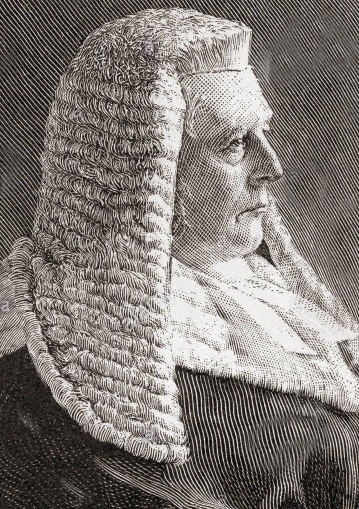

On 6th April 1863, Henry Carter, aged 20, was hanged for the murder of his sweetheart, 18 year-old Alice Hinkley, in December the previous year. The murder occurred in Bissell Street, Birmingham, and was relatively unusual for a ‘domestic’, as it involved a firearm, in this case a double-barrelled pistol. When the case came to Warwick Spring Assizes Carter’s defence was that the pistol had been discharged accidentally, but the jury was having none of it. They found him guilty, but with a recommendation to mercy. Mr Justice Willes (left) donned the black cap, and told Carter”

On 6th April 1863, Henry Carter, aged 20, was hanged for the murder of his sweetheart, 18 year-old Alice Hinkley, in December the previous year. The murder occurred in Bissell Street, Birmingham, and was relatively unusual for a ‘domestic’, as it involved a firearm, in this case a double-barrelled pistol. When the case came to Warwick Spring Assizes Carter’s defence was that the pistol had been discharged accidentally, but the jury was having none of it. They found him guilty, but with a recommendation to mercy. Mr Justice Willes (left) donned the black cap, and told Carter”

“I must implore you not to entertain any fond hope that the recommendation can save your life from the consequences of so awful and dreadful an act.”

He was right to be pessimistic. Home Secretary Sir George Grey was disinclined to be merciful, and Henry Carter was hanged. The newspaper reported thus:

“Yesterday morning Henry Carter was executed at the County Gaol, Warwick, in the presence of an immense assemblage of persons. It will be remembered that the culprit was tried at the recent assizes on the 28th ult. before Mr. Justice Willes, for the wilful murder of a young woman named Alice Hinkley, to whom he was paying his addresses, at Birmingham. He admitted when taken into custody that he had shot the unhappy girl. The execution took place at ten minutes after ten o’clock, and it is understood that the culprit confessed his crime ; but as Warwick is one of the gaols from which the press is rigorously excluded, any details are impossible to be given.”

Another account had more detail:

“Henry Carter, brass-founder, aged about twenty, was executed in front of the County Gaol at Warwick, on Thursday, for shooting with a pistol Birmingham, on the 4th of December last, his sweetheart. Alice Hinkley. The facts of the case have been recently reported. Carter had been Sunday-school teacher at Car’s Lane chapel, Birmingham, and spent the chief part of his time since his condemnation in religions devotions. On Thursday week a petition was forwarded the Secretary of State praying for commutation sentence, the grounds of Carter’s youth. An intimation that the the law must take its course was received on Saturday, and the warrant for execution once made out.

The services of Smith* of Dudley, Palmer’s executioner, were retained as hangman. The ceremony commenced shortly before ten o’clock on Thursday morning, when the prisoner attended prayers in the chapel of the gaol, then formed one of the procession of the prison officials to the pinioning room, and thence on to the scaffold. He was asked whether the pistol went off accidentally, and he said, “No. There was no quarrel between us while talking. I shook her hand, and kissed her before parting, and then shot her. It was through jealousy.” On reaching the scaffold in his prison dress he addressed the crowd below, warning them not to give way to similar feelings lest they should meet the fate which he was about to receive. and which, he well deserved. He then repeated a prayer from a book entitled “The Prisoner’s Memorial,” after which the bolt was removed and the drop fell. Death ensued almost instantly.”

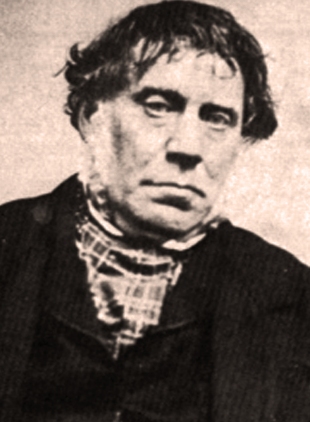

*George Smith (1805–1874, pictured right), popularly known as The Dudley Throttler , was an English hangman from 1840 until 1872. He was born in Rowley Regis in the West Midlands where he performed the majority of his executions. Although from a good family he became involved with gangs and petty crime in his early life, and was imprisoned in Stafford Gaol on several occasions for theft.

*George Smith (1805–1874, pictured right), popularly known as The Dudley Throttler , was an English hangman from 1840 until 1872. He was born in Rowley Regis in the West Midlands where he performed the majority of his executions. Although from a good family he became involved with gangs and petty crime in his early life, and was imprisoned in Stafford Gaol on several occasions for theft.

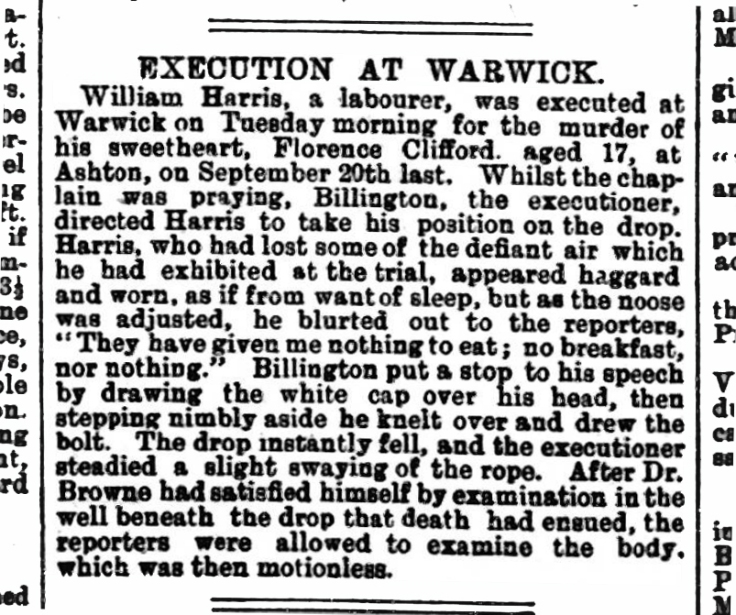

Carter was the last person to be publicly executed in Warwick, and the last to die in front of the old gaol. A new prison was built on Cape Road and the old gaol was converted into a militia barracks. There were to be seven more executions, the last being William Harris on 2nd January 1894. Harris, also known as Haynes, had murdered his girlfriend, Florence Clifford in Aston, Birmingham in September the previous year. The 17 year-old girl, tired of Harris’s brutal behaviour towards her, had decided to leave him, and went to her mother’s house to collect some clothes. Harris followed her there, and murdered her with an axe. He then went on the run, but gave himself up to Northamptonshire police. At his trial, he said:

“I wish I could have chopped the girl’s mother up, and then I should have been satisfied. I would have chopped her into mince-meat, and made sausages of her. I am ready for execution now.”

Defiant and unrepentant during his trial, Harris cut a sorrier figure when he went to the gallows.

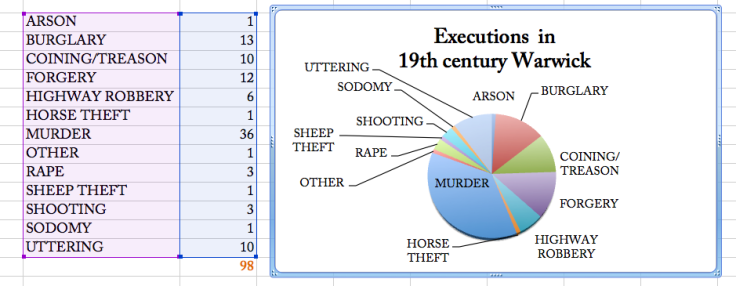

It is worth remembering that the death penalty was widely available for a large range of offences until penal reforms in 1835 saw the end of capital punishment for crimes other than murder or attempted murder. The chart below gives an analysis of executions in Warwick during the 19th century. “Uttering” was, basically what we would now call fraud, while “coining” was the crime of counterfeiting or otherwise interfering with currency. It was also considered to be high treason.