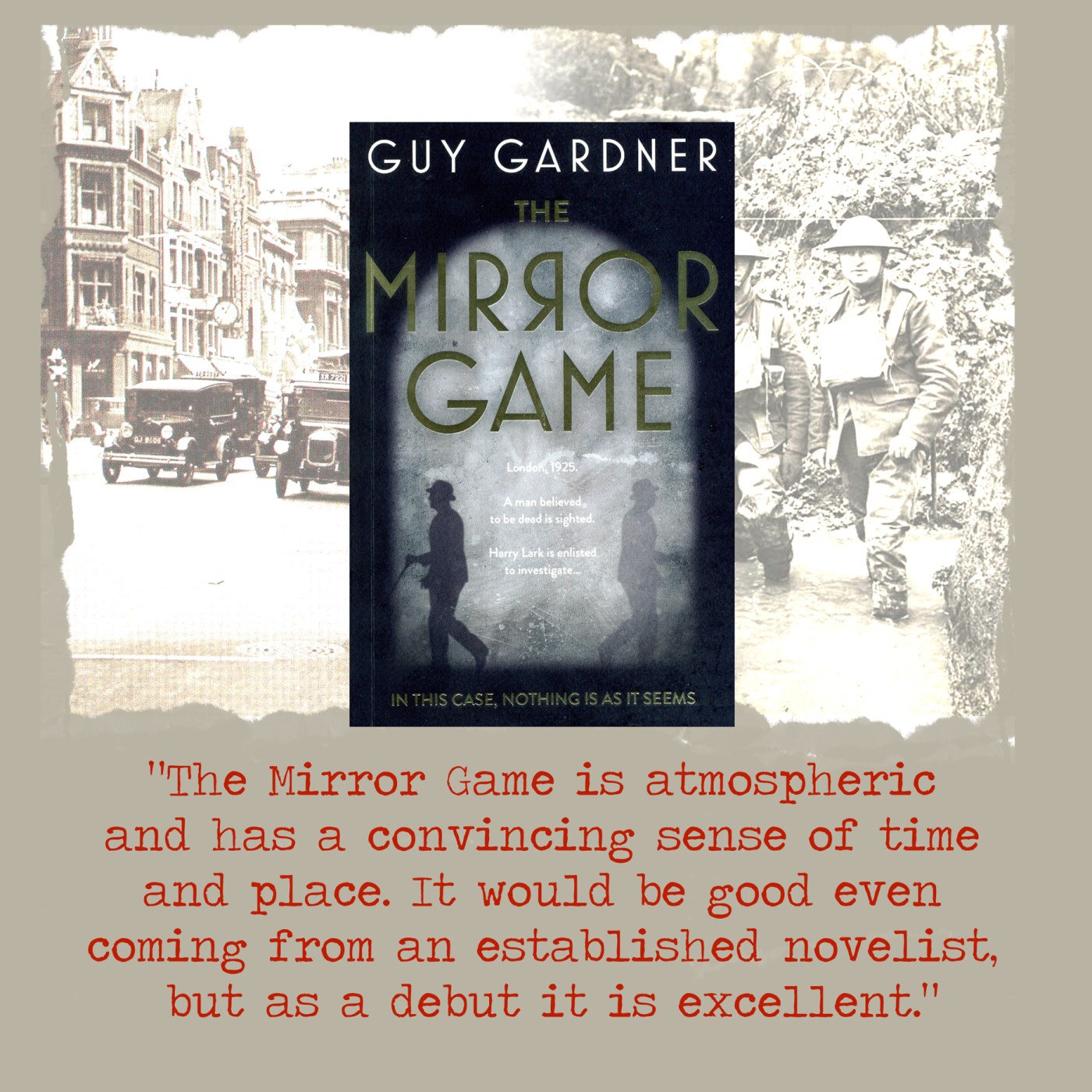

Even before I read the first page, this book ticked a number of important boxes for me, including:

1920s ✔️

London ✔️

Great War background ✔️

Beautifully imagined cover graphics ✔️

I’m happy to say my initial optimism was not to be shattered. So, what goes on? We are in 1925 and in a London that has borne relatively little structural damage from the recent war compared to what it was to suffer less that two decades later. The major damage, however is to the people and families of the city. Across Britain, the war has claimed the lives of 886,000 participants, mostly men between the ages of 18 and 40, and London has more than its fair share of widows, children without fathers and parents without sons.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate.

Harry’s search takes him to Harcourt’s father who throws him out on his ear. He then visits an exclusive gentleman’s club, where he asks one too many questions, and is beaten within an inch of his life by thugs in the pay of someone powerful. Helped by an old friend, retired policeman Bob Clements, he learns that Adrian Harcourt was listed as being killed in a firefight near a ruined French village, when the company he commanded were slaughtered. There were a mere handful of survivors, one of which was the son of an influential London gangster, Alec Ivers.

Harry Lark begins to get the sense that something terrible caused the death of most of Harcourt’s company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

As he tries to learn the truth Harry himself takes both mental and physical batterings, while there are a string of deaths around the fringes of the affair. His growing love for Ferderica seems to be reciprocated, but then they both receive a huge shock which turns the case on its head.

Author Guy Gardner’s day job – or, more likely, night job – was jazz pianist, but now he teaches piano at home in Dorset and is planning to write more novels. He also says he enjoys a glass of single malt, so I raise a glass of my favourite, Lagavulin, in his honour!

The book is certainly not short on action, intriguing characters and plot twists but, unsurprisingly, Guy Gardner is at his best when describing the occasions when music (Ferderica is a violinist, and Harry is a music journalist) is woven into the story. The Mirror Game is atmospheric and has a convincing sense sense of time and place. It would be good even coming from an established novelist, but as a debut it is excellent. It is published by The Book Guild, and is available now.

FOR MORE FICTION WITH A GREAT WAR BACKGROUND, CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW

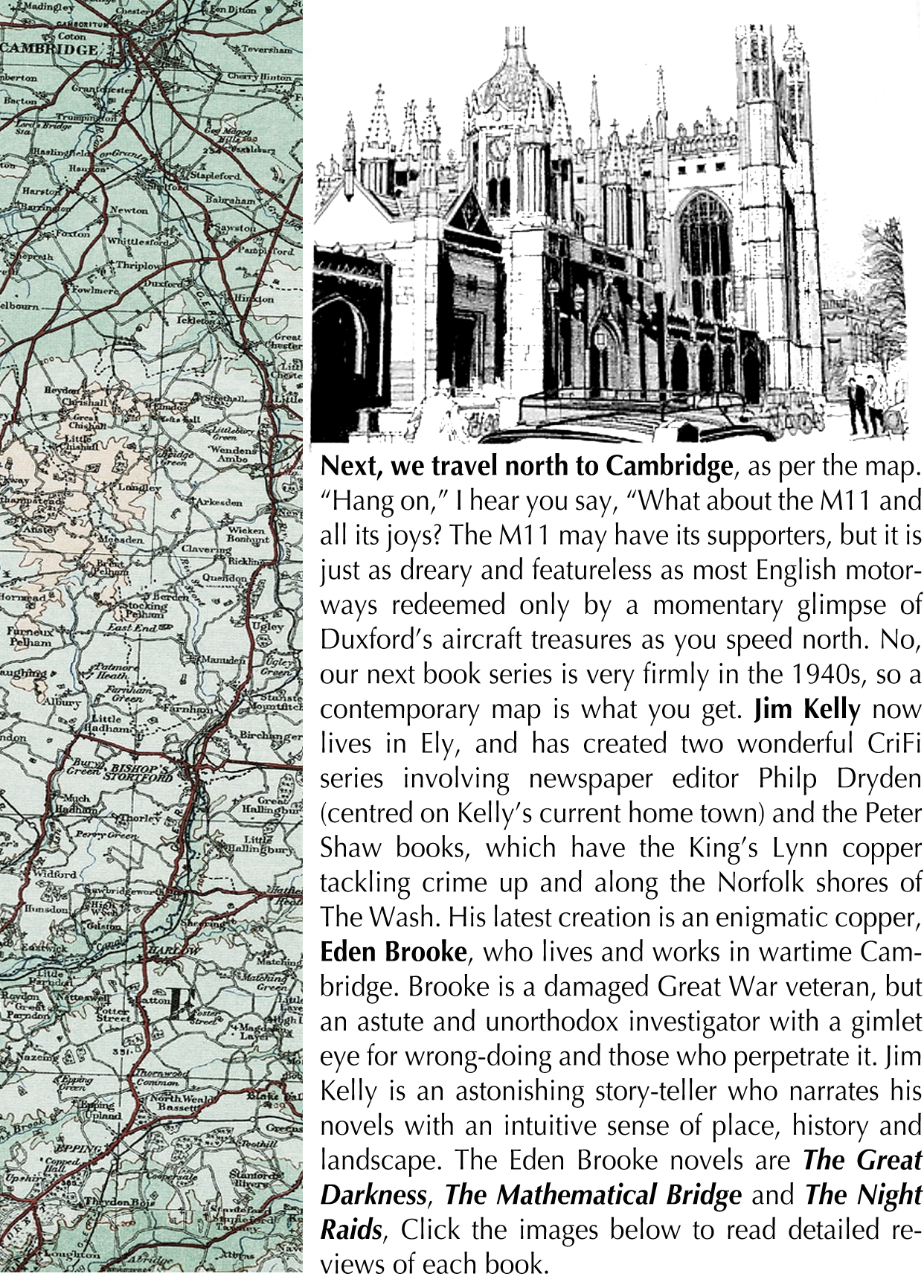

Jim Eldridge (left) and his aristocratic Detective Chief Inspector Edgar Saxe-Coburg are working their way around the best hotels in 1940s London, investigating murder We have had

Jim Eldridge (left) and his aristocratic Detective Chief Inspector Edgar Saxe-Coburg are working their way around the best hotels in 1940s London, investigating murder We have had  Lurking in the background of this tale is a man who is less than noble, but with more power than all the kings and queens sheltering in London’s best hotel suites. Henry ‘Hooky’ Morton is a London gangster who is building his empire on black market scams, the most profitable of which is his manipulation of the petrol market. We think of fuel supply – or lack of it – as a very modern problem, but in 1940, having fuel to put in your car was crucial to many organisations. Hooky Morton has a problem, though. Someone has infiltrated his gang, and is making him look stupid. Then, Hooky does something really, really stupid and, no nearer identifying the garotte killer or their motives, Saxe-Coburg becomes involved in investigating what is, for any copper, the worst crime of all.

Lurking in the background of this tale is a man who is less than noble, but with more power than all the kings and queens sheltering in London’s best hotel suites. Henry ‘Hooky’ Morton is a London gangster who is building his empire on black market scams, the most profitable of which is his manipulation of the petrol market. We think of fuel supply – or lack of it – as a very modern problem, but in 1940, having fuel to put in your car was crucial to many organisations. Hooky Morton has a problem, though. Someone has infiltrated his gang, and is making him look stupid. Then, Hooky does something really, really stupid and, no nearer identifying the garotte killer or their motives, Saxe-Coburg becomes involved in investigating what is, for any copper, the worst crime of all.

On his trail is a grotesque cartoon of a copper – DCI Dave Hicks. He lives at home with his dear old mum, has a prodigious appetite for her home-cooked food, is something of a media whore (he does love his press conferences) and has a shaky grasp of English usage, mangling idioms like a 1980s version of Mrs Malaprop.

On his trail is a grotesque cartoon of a copper – DCI Dave Hicks. He lives at home with his dear old mum, has a prodigious appetite for her home-cooked food, is something of a media whore (he does love his press conferences) and has a shaky grasp of English usage, mangling idioms like a 1980s version of Mrs Malaprop. “A fuchsia -pink shirt with outsize wing collar, over-tight lime green denim jeans, a brand new squeaky-clean leather jacket and, just for good measure, a black beret with white trim.”

“A fuchsia -pink shirt with outsize wing collar, over-tight lime green denim jeans, a brand new squeaky-clean leather jacket and, just for good measure, a black beret with white trim.”

What is happening then, in Murder Most Vile? All too often these days, I am a late arrival at the ball and this is the ninth in a series centred on a pair of investigators in 1950s England. Donald Langham is a London novelist, who runs an investigation agency with business partner Ralph Ryland. Langham’s wife, Maria Dupré, is a literary agent. Here, Langham is engaged by a rather unpleasant and misanthropic – but very rich – old man named Vernon Lombard. Lombard has a daughter and two sons, and the favourite one of the two boys, a feckless artist called Christopher, is missing.

What is happening then, in Murder Most Vile? All too often these days, I am a late arrival at the ball and this is the ninth in a series centred on a pair of investigators in 1950s England. Donald Langham is a London novelist, who runs an investigation agency with business partner Ralph Ryland. Langham’s wife, Maria Dupré, is a literary agent. Here, Langham is engaged by a rather unpleasant and misanthropic – but very rich – old man named Vernon Lombard. Lombard has a daughter and two sons, and the favourite one of the two boys, a feckless artist called Christopher, is missing.

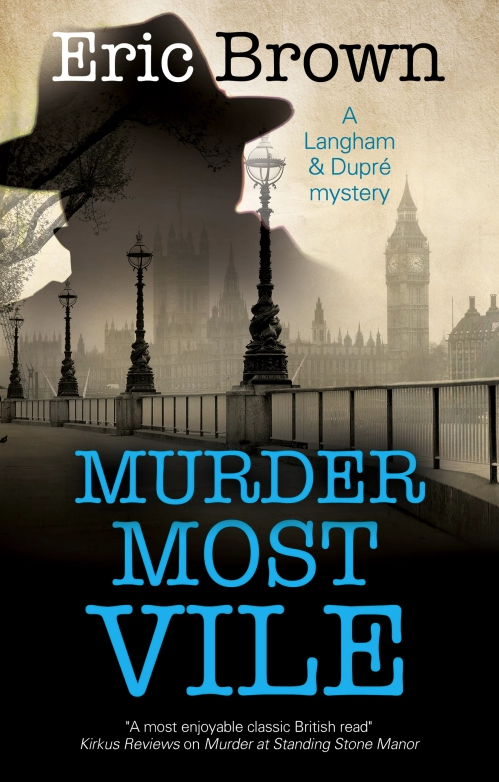

A rich widower, a self made industrialist, dies and leaves his fortune to be divided between his two nephews. One is a down-at-heel schoolmaster, the other a disreputable roué. The lucky man has to solve a cypher set by their late uncle. The good guy brings the cypher to Hester and Ivy. They solve the conundrum with by way of a knowledge of 18th century first editions, a journey to explore an ancient English church, and by breaking in to a family mausoleum.

A rich widower, a self made industrialist, dies and leaves his fortune to be divided between his two nephews. One is a down-at-heel schoolmaster, the other a disreputable roué. The lucky man has to solve a cypher set by their late uncle. The good guy brings the cypher to Hester and Ivy. They solve the conundrum with by way of a knowledge of 18th century first editions, a journey to explore an ancient English church, and by breaking in to a family mausoleum. Here, Tony Evans (right) indulges in the first of two shameless – but entertaining – instances of name-dropping. Our two sleuths, weary after a succession of difficult investigations, are enjoying some well-earned R & R in the resort of Whitby. So who do they meet? Think Irish writer and man of the theatre, blood, fangs …..? Gotcha! They are engaged by a fellow holidaymaker, a certain Mr B. Stoker to investigate the disappearance of a housemaid. She has been induced to leave her present employment to go and work for a rather dodgy doctor. Much skullduggery ensues, the housemaid is saved, and Mr Stoker says, “Hmm – this gives me an idea for a story.”

Here, Tony Evans (right) indulges in the first of two shameless – but entertaining – instances of name-dropping. Our two sleuths, weary after a succession of difficult investigations, are enjoying some well-earned R & R in the resort of Whitby. So who do they meet? Think Irish writer and man of the theatre, blood, fangs …..? Gotcha! They are engaged by a fellow holidaymaker, a certain Mr B. Stoker to investigate the disappearance of a housemaid. She has been induced to leave her present employment to go and work for a rather dodgy doctor. Much skullduggery ensues, the housemaid is saved, and Mr Stoker says, “Hmm – this gives me an idea for a story.”

Thus begins a thoroughly intriguing murder mystery, steeped in the religious politics of the time. For over one hundred and fifty years, religion had defined politics. Henry VIII and his daughters had burned their ‘heretics’, and although the strife between Charles I and Parliament was mainly to do with authority and representation, many of Oliver Cromwell’s adherents were strident in their opposition to the ways of worship practiced by the Church if England. Now, Charles II is King. He is reputed to have sired many ‘royal bastards’ but none that could succeed to the throne, and the next in line, his brother James, has converted to Catholicism. In most of modern Britain the schism between Catholics and Protestants is just a memory, but we only have to look across the Irish Sea for evidence of the bitter passions that can still divide society.

Thus begins a thoroughly intriguing murder mystery, steeped in the religious politics of the time. For over one hundred and fifty years, religion had defined politics. Henry VIII and his daughters had burned their ‘heretics’, and although the strife between Charles I and Parliament was mainly to do with authority and representation, many of Oliver Cromwell’s adherents were strident in their opposition to the ways of worship practiced by the Church if England. Now, Charles II is King. He is reputed to have sired many ‘royal bastards’ but none that could succeed to the throne, and the next in line, his brother James, has converted to Catholicism. In most of modern Britain the schism between Catholics and Protestants is just a memory, but we only have to look across the Irish Sea for evidence of the bitter passions that can still divide society.

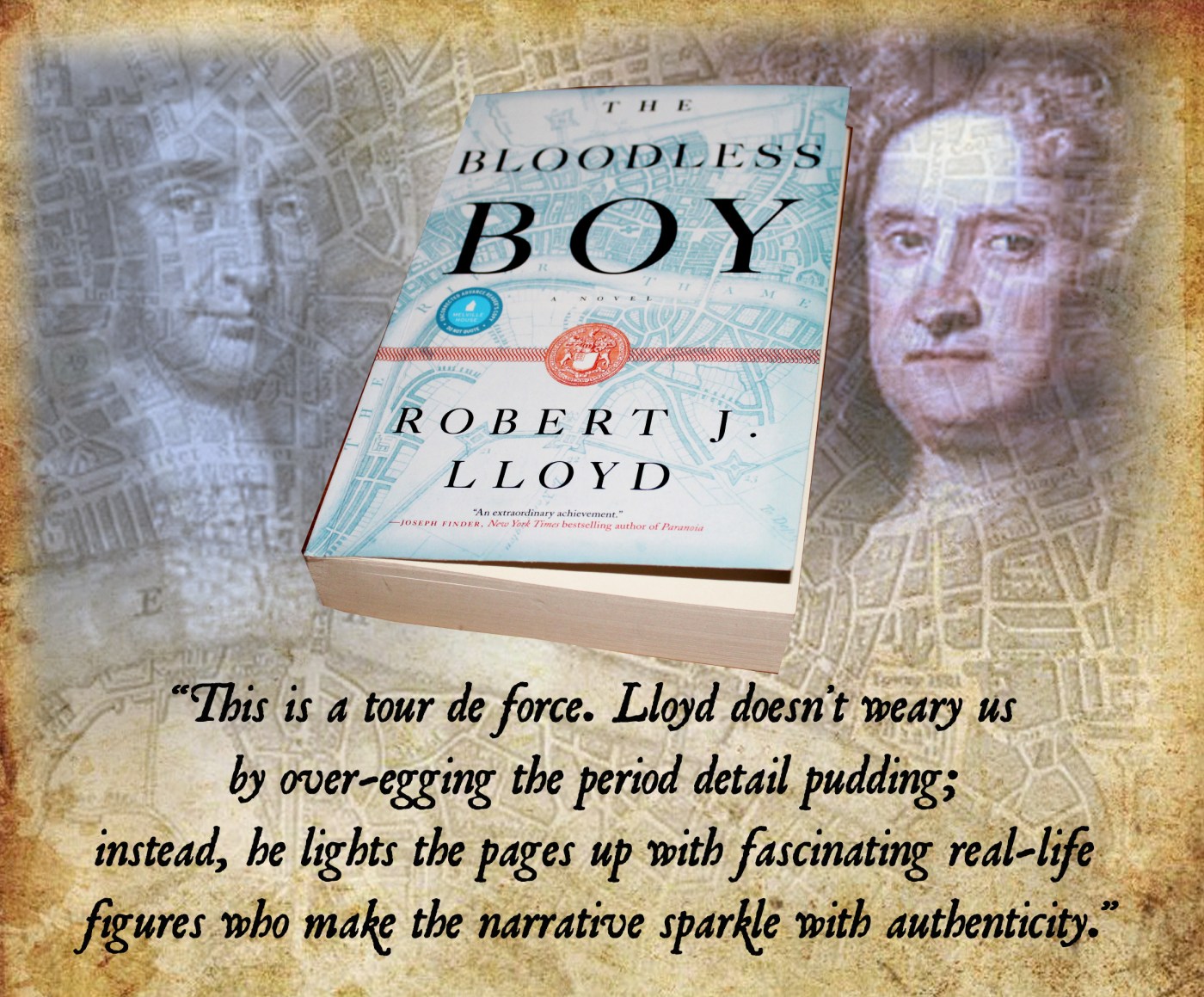

How on earth this superb novel spent many years floating around in the limbo of ‘independent publishing’ is beyond reason. While not quite in the ‘Decca rejects The Beatles‘ class of short sightedness, it is still baffling. The Bloodless Boy has everything – passion, enough gore to satisfy Vlad Drăculea, a sweeping sense of England’s history, a comprehensive understanding of 17th century science and a depiction of an English winter which will have you turning up the thermostat by a couple of notches. The characters – both real and fictional – are so vivid that they could be there in the room with you as you read the book.

How on earth this superb novel spent many years floating around in the limbo of ‘independent publishing’ is beyond reason. While not quite in the ‘Decca rejects The Beatles‘ class of short sightedness, it is still baffling. The Bloodless Boy has everything – passion, enough gore to satisfy Vlad Drăculea, a sweeping sense of England’s history, a comprehensive understanding of 17th century science and a depiction of an English winter which will have you turning up the thermostat by a couple of notches. The characters – both real and fictional – are so vivid that they could be there in the room with you as you read the book.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

There were nineteen B & M novels, beginning with Full Dark House in 2003, plus a quartet of graphic novels and short story collections. I say ‘were’, because although Christopher Fowler (left) is still with us, those who have read London Bridge Is Falling Down (2021) will know – and I am sorry if this is a spoiler – that old age and infirmity finally catches up with the venerable pair of detectives. Where to start to talk about this series? The author himself is, as far as I can judge, a modern and cosmopolitan fellow, but his love – and knowledge – of London is all embracing. Christopher Fowler is a one-off in contemporary writing, and completely individual, but speaking as an elderly chap with many years of reading behind me, I can best put him in context with great English writers of the last 150 years or so by looking at various aspects of the novels.

We are left to imagine what he looks like. He never uses violence as a matter of habit, but his inner rage fuels a temper which can destroy those who are unwise enough to provoke him. Why is he so bitter, so angry, so disgusted? Of himself, he says:

We are left to imagine what he looks like. He never uses violence as a matter of habit, but his inner rage fuels a temper which can destroy those who are unwise enough to provoke him. Why is he so bitter, so angry, so disgusted? Of himself, he says:

Investigating duos are always a reliable way to spin a police novel, and in this case we have Inspector Harvey Marmion and Sergeant Joe Keedy of the Metropolitan Police. Marmion is married to Ellen, with a son and daughter. Son Paul has been mentally damaged by his time on the Western Front, and has now disappeared leaving no clue as to his whereabouts, while daughter Alice – also a service police officer – is engaged to Keedy.

Investigating duos are always a reliable way to spin a police novel, and in this case we have Inspector Harvey Marmion and Sergeant Joe Keedy of the Metropolitan Police. Marmion is married to Ellen, with a son and daughter. Son Paul has been mentally damaged by his time on the Western Front, and has now disappeared leaving no clue as to his whereabouts, while daughter Alice – also a service police officer – is engaged to Keedy. Edward Marston

Edward Marston