The guns that began their incessant thunder in August 1914 are, at last, silent. The German field army has surrendered, the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet lies at anchor in Scapa Flow, and Wilhelm himself has abdicated. In Paris, the great, the good – but more importantly, the victorious – are assembling to pick the bones out of five years of carnage. Meanwhile, we meet the Rutherford family. Their home is in Thurso, on the stormy north eastern coast of Scotland. Jack is just one of nearly 900,000 British men to have paid what was poetically called ‘the supreme sacrifice’. His sisters are both now in France: Corran is with a charity in Dieppe, bringing some sort of education to young soldiers who have had academic opportunities denied them for the last five years. Stella is in Paris, having been engaged as one of the hundreds of typists needed to record the decisions and arguments in the drama shortly to be played out at Versailles. Alex is still on Royal Navy duties, with his ship keeping a watchful eye on a war that is still being fought between Russian Bolsheviks and the Tsarists they overthrew.The novel follows the lives and loves of the Rutherford girls.

Flora Johnston handles the historical background well. It is now widely acknowledged that the Treaty of Versailles did not end the war between Germany and her enemies. It merely put it in on hold for twenty years. There was not to be a new world, or anything remotely like the ‘land fit for heroes’ that optimists imagined, either in Britain or France,and certainly not in Germany. In vain did US President Wilson strive for some kind of settlement that would be for all time. Who can blame France – with 1.4 million dead, thousands of villages reduced to rubble, its industry shattered and a priceless architectural heritage destroyed – for wanting to make Germany pay?

We see 1919 through many different eyes, and this is a story skillfully told. Arthur, Corran’s teacher colleague is embittered by the sacrifices his own parents made to educate him, and white-knuckled with anger that, back home, his own family, protesting against the lack of jobs, are faced with baton charges by police. Rob Campbell, once Corran’s intended fiancée, is worn down and traumatised by his work as a battlefield surgeon. His fondest hope is purely escapist, and it is that one day he might be able to relive his glory days on the rugby pitch. But with so many of his fellow players rotting under the French and Belgian soil, what hope does he have?

The game of rugby is a powerful motif in this story. in an England-Scotland game in March 1914 the thirty young men are at the peak of fitness, chests bursting with pride. Too many of those chests would, in the coming turmoil, simply become targets for German bullets and shell fragments. On New Year’s Day 1920, the first game of any consequence to follow the war was played, between France and Scotland. It is a small and hesitant step forward, but there are too many missing names of the teamsheets.

The story is a remarkable blend of history, romance and social observation. Flora Johnston is a fly on the wall at a bitter ceremony in a young man’s bedroom that must have been repeated countless times across Britain and, indeed, France, and Germany:

“She felt again the overwhelming sadness of sorting through Jack’s possessions yesterday. All over the country there were houses like this, filled with the ephemera of hundreds of thousands of lives that had unexpectedly ceased to exist. Clothes and footballs, bicycles and egg collections, razors and comics and diaries and gramophone records. So much of it: surely far too much for the nations attics or rubbish heaps or junk shops to absorb.”

The Peacemakers of Paris reaches out to so many different readers. WW1 buffs who appreciated Birdsong and Pat Barker’s trilogy will find something here. Those who like romance, a hint of heartbreak, but an optimistic ending will also be happy. Most importantly, anyone who enjoys a novel which is well researched with convincing characters will not be disappointed. Published by Allison & Busby, the book is available now.

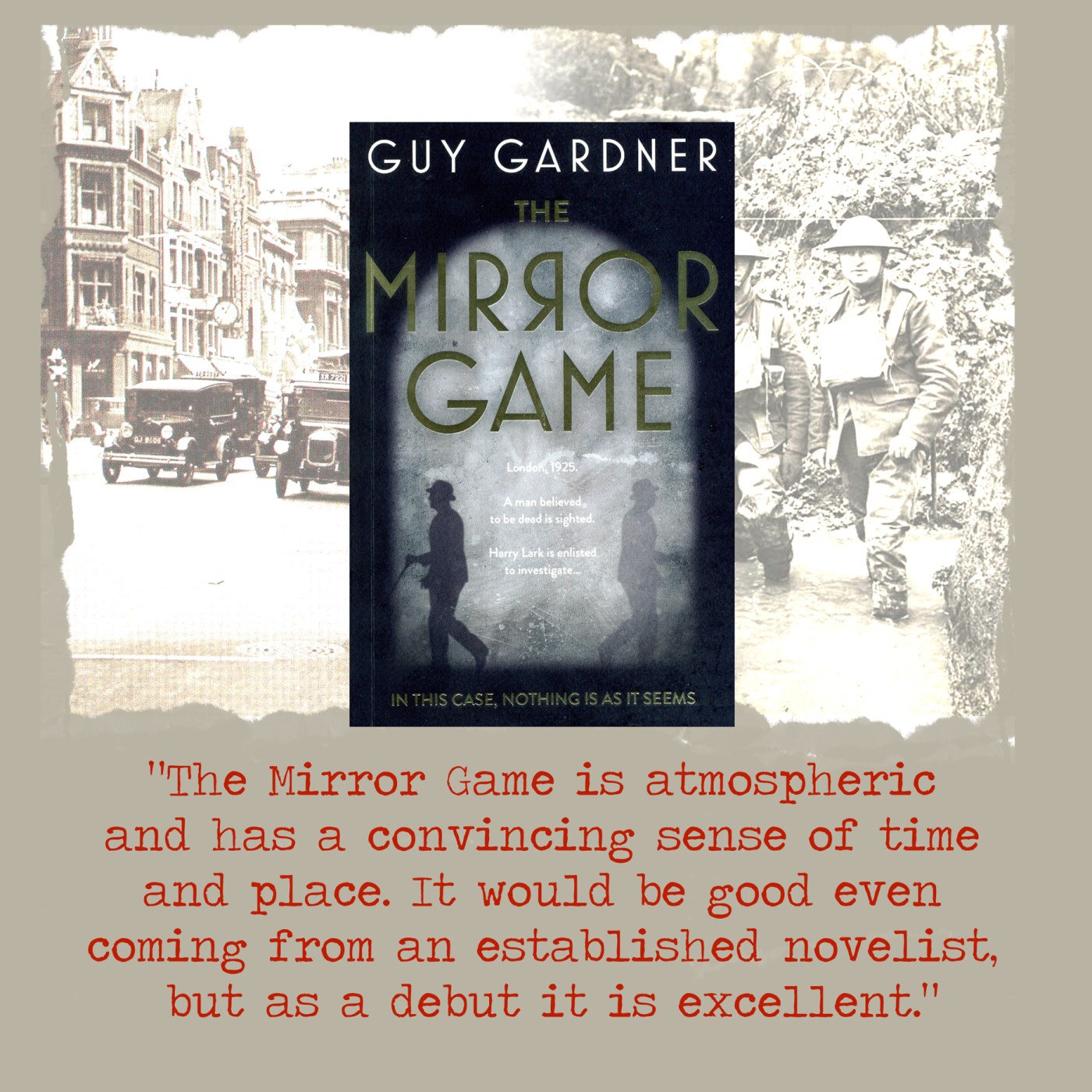

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate. company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

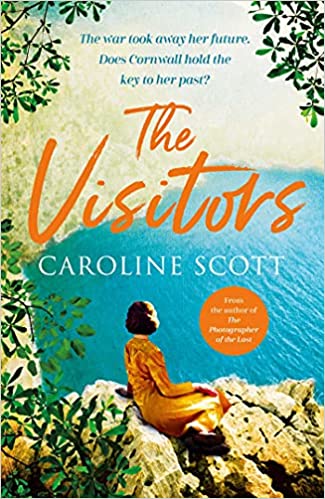

England, 1923. Like thousands upon thousands of other young women, Esme Nicholls is a widow. Husband Alec lies in a functional grave in a military cemetery in Flanders. His face remains in a few photographs, and in her memories. Left penniless, she ekes out a living by writing a nature-notes feature for a northern provincial newspaper, and serving as a personal assistant to an older widow, Mrs Pickering. Mrs P has the advantage of being able to visit her husband’s grave whenever she wants, as he was not a victim of the war.

England, 1923. Like thousands upon thousands of other young women, Esme Nicholls is a widow. Husband Alec lies in a functional grave in a military cemetery in Flanders. His face remains in a few photographs, and in her memories. Left penniless, she ekes out a living by writing a nature-notes feature for a northern provincial newspaper, and serving as a personal assistant to an older widow, Mrs Pickering. Mrs P has the advantage of being able to visit her husband’s grave whenever she wants, as he was not a victim of the war. Caroline Scott (right) treats us to a high summer in Cornwall, where every flower, rustle of leaves in the breeze and flit of insect is described with almost intoxicating detail. Readers who remember her previous novel When I Come Home Again will be unsurprised by this detail. In the novel, she references that greatest of all poet of England’s nature, John Clare, but I also sense something of Matthew Arnold’s poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis, so memorably set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Caroline Scott (right) treats us to a high summer in Cornwall, where every flower, rustle of leaves in the breeze and flit of insect is described with almost intoxicating detail. Readers who remember her previous novel When I Come Home Again will be unsurprised by this detail. In the novel, she references that greatest of all poet of England’s nature, John Clare, but I also sense something of Matthew Arnold’s poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis, so memorably set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

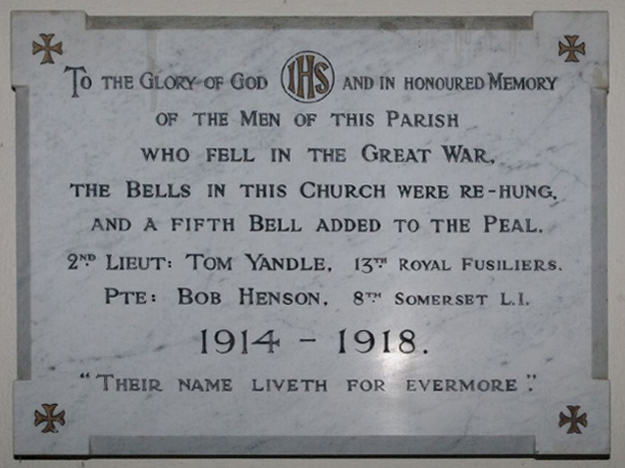

Robert’s regiment, The Somerset Light Infantry, has a distinguished history. It was founded in 1685 as part of King James II’s response to the Monmouth Rebellion. Under various titles it fought in every major conflict including the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, the Afghan Wars and the Boer War until it was finally merged with other regiments to become The Light Infantry in 1968.

Robert’s regiment, The Somerset Light Infantry, has a distinguished history. It was founded in 1685 as part of King James II’s response to the Monmouth Rebellion. Under various titles it fought in every major conflict including the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimean War, the Afghan Wars and the Boer War until it was finally merged with other regiments to become The Light Infantry in 1968.

The poet Vernon Scannell, himself a veteran of WW2 wrote a haunting poem he called The Great War. The closing lines are:

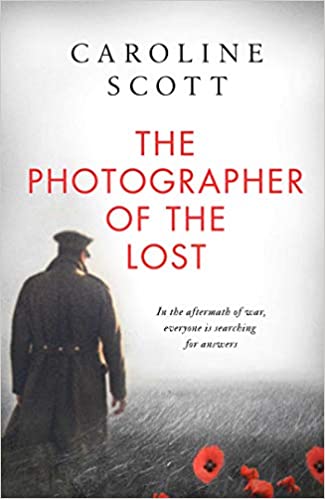

The poet Vernon Scannell, himself a veteran of WW2 wrote a haunting poem he called The Great War. The closing lines are: In her 2014 novel Those Measureless Fields she began her own personal exploration of what happened to the men and families who had to pick up the pieces of their lives after the Armistice. She followed this in 2019 with what was, for, me one of the books of the year,

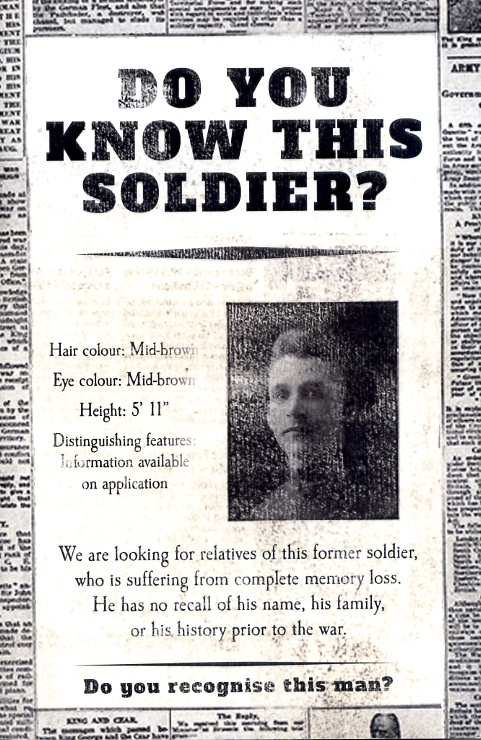

In her 2014 novel Those Measureless Fields she began her own personal exploration of what happened to the men and families who had to pick up the pieces of their lives after the Armistice. She followed this in 2019 with what was, for, me one of the books of the year,  At a rehabilitation centre in the Lake District, Haworth tries to find the key that will unlock Adam’s memory. James and his boss, Alec Shepherd, take a bold decision. They release a photograph of Adam, and what little they know of him, to the national press. This triggers a wave of mothers, wives and sisters who yearn for the impossible – a virtual resurrection of their lost son, husband and brother. From the tragic queue of broken hearted souls, three women seem to be the most convincing. They are Celia Daker, who believes that Adam is her missing son, Robert, Anna Mason, a young wife who dares to dream that she is no longer a widow, and Lucy Vickers a sister who is now bringing up the children of her lost brother.

At a rehabilitation centre in the Lake District, Haworth tries to find the key that will unlock Adam’s memory. James and his boss, Alec Shepherd, take a bold decision. They release a photograph of Adam, and what little they know of him, to the national press. This triggers a wave of mothers, wives and sisters who yearn for the impossible – a virtual resurrection of their lost son, husband and brother. From the tragic queue of broken hearted souls, three women seem to be the most convincing. They are Celia Daker, who believes that Adam is her missing son, Robert, Anna Mason, a young wife who dares to dream that she is no longer a widow, and Lucy Vickers a sister who is now bringing up the children of her lost brother.