A tad early for a Valentine, but hey ho . . . . . . .

She loves me, she loves me not . . . .

In the pink . . .

THE LOVE DETECTIVE: THE NEXT LEVEL is written by Angela Dyson, published by Matador, and is out now.

THE LOVE DETECTIVE: THE NEXT LEVEL is written by Angela Dyson, published by Matador, and is out now.

The impossibly geriatric constabulary codgers Arthur Bryant and John May return for another journey into London’s darkside in pursuit of those who kill. This time, the killer appears to be armed with a trocar – an obscure but deadly surgical instrument originally intended to penetrate the body allowing gases or fluid to escape. From the undergrowth of a copse on Hampstead Heath, and the unforgiving undertow of the Thames, via an exclusive multi-story apartment complex, to the pedestrian walkway of a Thames bridge, the victims seems to have nothing in common except the time of their demise – the deadly hour of 4.00 am.

Bryant and May – and the rest of the Peculiar Crimes Unit – have been threatened with closure before, but this time their impatient and disapproving police bosses mean business. The PCU, both collectively and individually flounder around trying to work out what connects the corpses, and who is expertly wielding the trocar. Like Andrew Marvell’s ‘Time’s Winged Chariot’, the accountants and political schemers of the Metropolitan Police are ‘hurrying near’, and failure to catch this killer will certainly mean that the shambolic HQ of the Peculiar Crimes Unit on Caledonian Road will soon be in need of new tenants.

Bryant and May – and the rest of the Peculiar Crimes Unit – have been threatened with closure before, but this time their impatient and disapproving police bosses mean business. The PCU, both collectively and individually flounder around trying to work out what connects the corpses, and who is expertly wielding the trocar. Like Andrew Marvell’s ‘Time’s Winged Chariot’, the accountants and political schemers of the Metropolitan Police are ‘hurrying near’, and failure to catch this killer will certainly mean that the shambolic HQ of the Peculiar Crimes Unit on Caledonian Road will soon be in need of new tenants.

Don’t be misled by the jokes, delightful cultural references, and Arthur’s frequent put-downs of the PCU’s hapless boss, most of which go over Raymond Land’s head but, fortunately, not ours. Physicists will probably say that their world has different rules, but in literature light can only exist relative to darkness, and Fowler does not allow the chiffon gaiety within the Peculiar Crimes Unit to disguise a dystopian London woven from a much darker thread. He says:

“Approaching midnight, the black and grey striped concourse of King’s Cross Station remained almost as busy as it had been during the day. Some Italian students appeared to be having a picnic under the station canopy. A homeless girl ms on her knees next to a lengthy cardboard message explaining her circumstances. A Jamaican family dressed in home-made ecclesiastical vestments were warning everyone that hell awaited sinners. A phalanx of bachelorettes in tiny silver dresses, strappy shoes and bunny ears marched past, heading to their next destination like soldiers on a final tour of duty. Inside the station, tourists were still lurking round the Harry Potter trolley that had been originally set there as a joke by the station guards, then monetized when queues appeared. As flinty-eyed and mean as it had ever been, London was good at making everyone pay.”

If a better paragraph about London has been written in recent years, I have yet to read it

Fowler’s London is a place where the same streets, courtyards, alleys and highways have been walked for centuries; Roman legionaries, Norman functionaries, medieval merchants, Tudor politicians, Restoration poets, Georgian gamblers, Victorian philanthropists, Great War Tommies, and now City spivs with their dreams and nightmares spinning about in front of them on their smartphones – all have played their part in treading history down beneath their feet into a compressed and powerful seam of memory. This memory, whether they know it or not, affects the lives of those who live, work, lust, learn and – ultimately – die in London. Other writers, notably Peter Ackroyd, have been drawn to this lodestone and tapped into its power. Some authors have taken up the theme but befuddled readers with too much arcane psychogeography. Fowler gets it right. Every single time. With every sentence of every paragraph of every chapter.

Bryant is neither Mr Pastry, Charles Pooter nor Mr Bean. He is as sharp as a tack despite such running gags as his coat pockets being full of fluff covered boiled sweets long since disappeared from English shelves. If we knew no better, we might describe him as having a personality disorder somewhere on the autism spectrum, but there are precious moments in The Lonely Hour where the old man brings himself up short with the realisation that he is, most of the time, chronically selfish.

Thanks to Bryant’s genius, the mystery is solved and the killer brought to justice, but these are certainly the grimmest days ever for the PCU, and as this brilliantly entertaining story reaches its conclusion, Fowler (right) slowly but irrevocably turns the tap marked Darkness to its fully open position. The Lonely Hour is published by Doubleday and is out now.

Thanks to Bryant’s genius, the mystery is solved and the killer brought to justice, but these are certainly the grimmest days ever for the PCU, and as this brilliantly entertaining story reaches its conclusion, Fowler (right) slowly but irrevocably turns the tap marked Darkness to its fully open position. The Lonely Hour is published by Doubleday and is out now.

London. 1873. It would be another fourteen years before a gentleman calling himself a Consulting Detective would make his first appearance in Beeton’s Christmas Annual, but Matthew Grand and James Batchelor are just that – people consult them, and they try to detect things. That is pretty much where any resemblance to the residents of 221B Baker Street ends. Neither Grand nor Batchelor is nice but dim, nor is either given to bashing out a melancholy bit of Mendelssohn on a Stradivarius. Matthew Grand, though, has seen military service; rather than battling the followers of Sher Ali Khan in Afghanistan, he has had the chastening experience of fighting his fellow Americans during the War Between The States a decade earlier. While James Batchelor is an impecunious former member of The Fourth Estate, his colleague comes from wealthy New Hampshire stock.

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery:

The River Thames plays a central part in The Ring. Although Joseph Bazalgette’s efforts to clean it up with his sewerage works were almost complete, the river was still a bubbling and noxious body of dirty brown effluent, not helped by the frequent appearance of human bodies bobbing along on its tides. In this case, however, we must say that the bodies come in instalments, as someone has been chopping them to bits. PC Crossland makes the first grisly discovery:

“… he knew exactly what the white thing was. It was the left side of what had once been a human being, sliced neatly at the hip and below the breast. There was no arm. No head. No legs.”

Trow gives us a Gilbertian cast of comedy coppers, in this case the River Police, led by the elephantine Inspector Bliss. While Bliss and his minions are trying to put together a case – and also the various limbs and organs of an unfortunate woman – Grand and Batchelor are visited by Selwyn Byng, an unseemly and ramshackle character, who believes his wife has been abducted, and has the ransom note to prove it. Byng may look cartoonish, and lack moral fibre; “Where’s your stiff upper lip?” “Underneath this loose flabby chin!” (quoted with due reverence to Tony Hancock and Kenneth Williams) but he has a bob or two, and so our detectives take on the search for the missing Emilia Byng.

It occurs to me that in dismissing any resemblance between H&W and G&B I am missing out one very important personage, and that is the housekeeper. The much revered Mrs Hudson is felt, rather than seen or heard, but Mrs Rackstraw is another matter entirely. The formidable woman dominates the apartment supposedly ruled over by the two young gentlemen:

“Mrs Rackstraw had been brought up in a God-fearing household and didn’t really hold with young gentlemen of their calibre not going to church. Had they been asked, both Grand and Batchelor would have preferred the constant nagging; her frozen silence and the way the boiled eggs bounced in their cups as she slammed them down on the table was infinitely worse.”

MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

MJ Trow (right) has been entertaining us for over thirty years with such series at the Inspector Lestrade novels and the adventures of the semi-autobiographical school master detective Peter Maxwell. Long-time readers will know that jokes are never far away, even when the pages are littered with sudden death, violence and a profusion of body parts. Grand and Batchelor eventually solve the mystery of what happened to Emilia Byng, both helped and hindered by the ponderous ‘Daddy’ Bliss and a random lunatic, recently escaped from Broadmoor. Trow writes with panache and a love of language equalled by few other British writers. His grasp of history is unrivalled, but he wears his learning lightly. The Ring is a bona fide crime mystery, but the gags are what lifts the narrative from the ordinary to the sublime:

“They adjusted their chairs and faced the wall. Mr and Mrs Gladstone stared back at them from their sepia photographs, jaws of granite and eyes of steel. Since he was the famous politician and she was merely loaded and fond of ice-cold baths, he sat in the chair and she stood at his shoulder, restraining him, if the rumours were true, from hurtling out of Number Ten in search of fallen women.”

The Fully Booked review of The Island, the previous Grand and Batchelor mystery, is here. The Ring is published by Severn House, and will be out on 28th September.

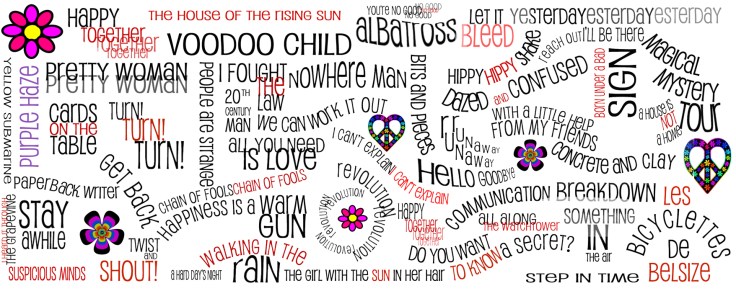

If a more extraordinary duo of fictional detectives exists than Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May, then I have yet to discover them. The peculiar pair return in Hall of Mirrors for their fifteenth outing, and this time not only are they far from their beloved London, but we see a pair of much younger coppers on their beat in the 1960s. Fowler’s take on the period is typified by each of the fifty chapters of the novel bearing the title of a classic pop hit. We are also reminded of the strange fashions of the day.

If a more extraordinary duo of fictional detectives exists than Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May, then I have yet to discover them. The peculiar pair return in Hall of Mirrors for their fifteenth outing, and this time not only are they far from their beloved London, but we see a pair of much younger coppers on their beat in the 1960s. Fowler’s take on the period is typified by each of the fifty chapters of the novel bearing the title of a classic pop hit. We are also reminded of the strange fashions of the day.

“Two young men in Second World War army uniforms painted with ‘Ban The Bomb’ slogans were arguing with a pair of Chelsea Pensioners who clearly didn’t take kindly to military outfits being worn by trendy pacifists. They were briefly joined by a girl wearing a British sailor’s uniform with a giant iridescent fish on her head.”

In attempt to keep them out of trouble, our heroes are given the task of being minders to an important witness in a fraud trial, but Monty Hatton-Jones is due at a country weekend party deep in rural Kent, and so John and Arthur must accompany him to Tavistock Hall. What follows is a delicious take on the Golden Age country house mystery, with improbable murders, secret passages, an escaped homicidal maniac and suspects galore. Things are complicated by nearby military manoeuvres involving the British army and their French counterparts. Fowler (above) reprises the great gag from Dr Strangelove – “Gentlemen – you can’t fight in here. This is the War Room!” Captain Debney, the British Commanding Officer is having a bad day.

“The menu for tonight’s hands Across The Water dinner has already gone up the Swanee. We had terrible trouble getting hold of courgettes, and now I hear there’s no custard available. I don’t want anything else going wrong. These are international war games. We can’t afford to have anyone hurt.”

The urbane John May is quite at home in the faded grandeur of Tavistock Hall, but Arthur is like a fish out of water. He also has an aversion to the countryside.

“It appeared to be the perfect Kentish evening, pink with mist and fresh with the scent of the wet grass. Bryant looked at it with a jaundiced eye. There was mud everywhere, the cows stank, and were all those trees really necessary? As a child he had been terrified of the bare, sickly elm in his street with a branch that scarped at his bedroom window like a witch’s hand and sent him under the blankets.”

As usual with the B & M books, the jokes come thick and fast, but we are reminded that Fowler is a perceptive and eloquent commentator on the human condition. Arthur investigates the local parish church as its rector, Revd Trevor Patethric is a house guest – and suspect.

“Bryant pushed open the church door and entered. He had never felt comfortable in the houses of God, associating them with gruelling rites of childhood: saying farewell to dead grandfathers, and the observance of distant, obscure ceremonies involving hushed prayers, peculiarly phrased bible passages, muffled tears and shamed repentance.”

Eventually, of course, the pair – mostly through Arthur’s twisted thought processes – solve the crimes. Prior to revealing his theories on the murder to the assembled guests, however, Bryant has a slight misfortune with a missing painting hidden in a very unswept chimney. Covered in soot, he somehow lacks the gravitas of a Poirot or a Marple.

“Bryant had made a desultory attempt to wipe his face, but the result was more monstrous than before. He rose before them now, a lunatic lecturer in the physics of murder.”

Reading a crime novel shouldn’t be about being educated, but Hall of Mirrors teaches us many things. Those who didn’t already know will learn that Christopher Fowler is a brilliant writer. He is, in my view, out on his own in the way he weaves a magic carpet from a dazzling array of different threads: there is uniquely English humour, the sheer joy of the eccentricities of our language and landscape, labyrinthine plotting, and an array of arcane cultural references which will surely have Betjeman beaming down from heaven. Those of us who, smugly perhaps, consider ourselves as old Bryant & May hands will also now know the origins of Arthur’s malodorous scarf and also his cranky, clanky Mini.

Amidst the gags, the fizzing dialogue and the audacious plot twists Fowler waves his magic wand, and with the lightest of light touches dusts a page near the very end with poignancy and great compassion. Look out for the section that ends:

“Bryant looked in his mirror to try and catch another glimpse of them, but they had disappeared, ghosts of a London yet to come.”

And do you want to know the best five words of the entire book? I’ll tell you:

Hall of Mirrors is published by Quercus, and is available from 22nd March.