Detective Inspector Eden Brooke, Jim Kelly’s 1940s Cambridge copper returns for his third case, in The Night Raids. Those readers who met Brooke in The Great Darkness and The Mathematical Bridge (the links will take you to my reviews) will know that he is cultured, educated, but afflicted with an aversion to bright light as a result of horrific treatment by his Turkish captors during The Great War. One consequence is that he must wear spectacles with special lenses; another is that finds sleep both difficult and troubled, in that when he when he can find repose, his dreams are stark and threatening. He lives in Cambridge with his wife Claire and two grown up children, of whom Joy is a nurse like her mother, while Luke is in the army. We learn that he is currently training with Special Forces. Because of his condition, Brooke is something of what used to be called a night owl. He is most at ease when he is outside, enveloped in the still watches of the night, and he has regular ports of call such as an all-night tea stall, a friend who is an air-raid observer, and a college porter.

Cambridge sits on the Western edge of the Fen Country – formerly a vast expanse of freshwater peat bog, meres and ever-changing rivers. By the time in which the book is set, the Fen had long since been tamed by numerous arrow-straight drainage channels and sluices, but in the Eden Brooke stories it sits out there, beyond the lights of the town, like a huge dark and silent presence. Water is, in fact, an essential theme of these novels. Brooke himself swims in the river for exercise and contemplation; it is also a place where people die, sometimes by their own hand, but also at the hands of others.

In Night Raids we see some of the story through the eyes of a crew of a German Heinkel bomber. Their mission is to destroy an essential bridge over the river; the bridge, crucially, carries the railway taking vital men and munitions to the east coast, where invasion is a daily expectation.The bombers come over at night, and have so far failed to destroy the bridge. What they have done, however, is unload some of their bombs on residential areas of the town, and inside one of the terraced houses wrecked by the raid, Brooke finds the body of an elderly woman. Her death is clearly attributable to Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe, but the fact that her left ring finger and middle finger have been removed with a hacksaw cannot, sadly be laid at the door of the Reichsmarschall.

In Night Raids we see some of the story through the eyes of a crew of a German Heinkel bomber. Their mission is to destroy an essential bridge over the river; the bridge, crucially, carries the railway taking vital men and munitions to the east coast, where invasion is a daily expectation.The bombers come over at night, and have so far failed to destroy the bridge. What they have done, however, is unload some of their bombs on residential areas of the town, and inside one of the terraced houses wrecked by the raid, Brooke finds the body of an elderly woman. Her death is clearly attributable to Hermann Goering’s Luftwaffe, but the fact that her left ring finger and middle finger have been removed with a hacksaw cannot, sadly be laid at the door of the Reichsmarschall.

When one of the dead woman’s granddaughters goes missing, along with her naturalised Italian boyfriend, Brooke can only look on in frustration as the case becomes more complex, and threatens to spin out of control. In what seems to be a totally unconnected incident, Brooke has discovered that someone – either intentionally or by accident – has released a pollutant into the river, possibly as a result of black market skullduggery. Once again, the river itself becomes a key element in the story. A body is discovered submerged near a fish farm which breeds pike, a delicacy served at High Table in some of the colleges. Bodies in rivers are commonplace in crime fiction, but this is as haunting and macabre as anything I have ever read:

“Boyle bent down to see if he could feel her breath between the blue lips, but the slightly bloated flesh, and the glazed eyes, told Brooke that she’d been dead for several days. The still-flowing blood told a lie. The pike had nibbled at the flesh but these wounds were puckered and bleached. The blood ran from black leeches which dotted her neck and legs, secreting their magic enzyme, which had stopped the blood from clotting. They stood back in silence as the cold corpse bled.”

Jim Kelly is one of our finest writers. Were I ever to be asked what my Desert Island third book choice would be, after the Bible and a complete Shakespeare, it would be a complete works of Jim Kelly. In The Night Raids he conjures up a narrative tour de force which combines the Cambridge murders, an exploitative criminal gang and the malevolent intentions of the Luftwaffe – into a dramatic and breathtaking final act. The Night Raids is published by Allison & Busby and is out now.

FOR MORE ON JIM KELLY CLICK THIS LINK

eing a middle class British father and grandfather, the concept of abandoning a newly born baby is totally beyond my experience of life and (the fault is perhaps mine) my comprehension. The fact is, however, that since Adam had his way with Eve, biology has trumped human intention, and babies have come into the world unloved and unwanted. Thankfully, there have been charitable institutions over the centuries which have done their best to provide some kind of home for foundlings. Abandoning babies is not something consigned to history: modern Germany has its Babyklappe, and Russia its Колыбель надежды – literally hatches – rather like an old fashioned bank deposit box – built into buildings where babies can be left. Back in time, Paris had its Maison de la Couche pour les Enfants Trouvés while in Florence the Ospedale degli Innocenti is one of the gems of early Renaissance architecture. London had its Foundling Hospital, and it is the centre of The Foundling, the new novel by Stacey Halls.

eing a middle class British father and grandfather, the concept of abandoning a newly born baby is totally beyond my experience of life and (the fault is perhaps mine) my comprehension. The fact is, however, that since Adam had his way with Eve, biology has trumped human intention, and babies have come into the world unloved and unwanted. Thankfully, there have been charitable institutions over the centuries which have done their best to provide some kind of home for foundlings. Abandoning babies is not something consigned to history: modern Germany has its Babyklappe, and Russia its Колыбель надежды – literally hatches – rather like an old fashioned bank deposit box – built into buildings where babies can be left. Back in time, Paris had its Maison de la Couche pour les Enfants Trouvés while in Florence the Ospedale degli Innocenti is one of the gems of early Renaissance architecture. London had its Foundling Hospital, and it is the centre of The Foundling, the new novel by Stacey Halls. Bess Bright is a Shrimp Girl. Her father gets up at the crack of dawn to buy Essex shrimps from Billingsgate Market, and Bess puts the seafood in the brim of a broad hat and, clutching a tiny tankard to measure them out, she walks the streets of

Bess Bright is a Shrimp Girl. Her father gets up at the crack of dawn to buy Essex shrimps from Billingsgate Market, and Bess puts the seafood in the brim of a broad hat and, clutching a tiny tankard to measure them out, she walks the streets of  elling shrimps from the brim of your hat is not an occupation destined to provide sufficient funds to keep a growing child, and so Bess presents herself and baby Clara at

elling shrimps from the brim of your hat is not an occupation destined to provide sufficient funds to keep a growing child, and so Bess presents herself and baby Clara at

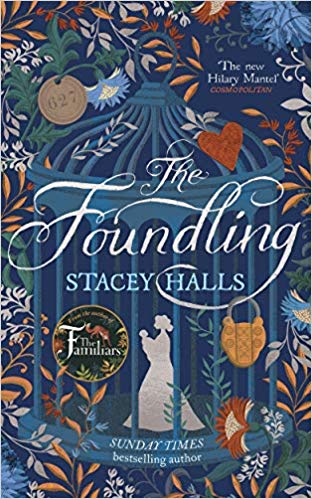

ow – and where – Bess finds her missing daughter is for you to discover, but I promise that The Foundling is ingenious, delightful, and the author’s skills as a storyteller are magnetic. The attention to detail and the period authenticity are things to be wondered at, but what elevates this novel above the humdrum is how Stacey Halls conjures up our sheer emotional investment in the characters, each one beautifully observed. Art lovers will recognise the painter – and the title – of the picture below and, were he alive to read it, the great observer of London life would thoroughly approve of The Foundling, which is published by Manilla Press and is out on

ow – and where – Bess finds her missing daughter is for you to discover, but I promise that The Foundling is ingenious, delightful, and the author’s skills as a storyteller are magnetic. The attention to detail and the period authenticity are things to be wondered at, but what elevates this novel above the humdrum is how Stacey Halls conjures up our sheer emotional investment in the characters, each one beautifully observed. Art lovers will recognise the painter – and the title – of the picture below and, were he alive to read it, the great observer of London life would thoroughly approve of The Foundling, which is published by Manilla Press and is out on

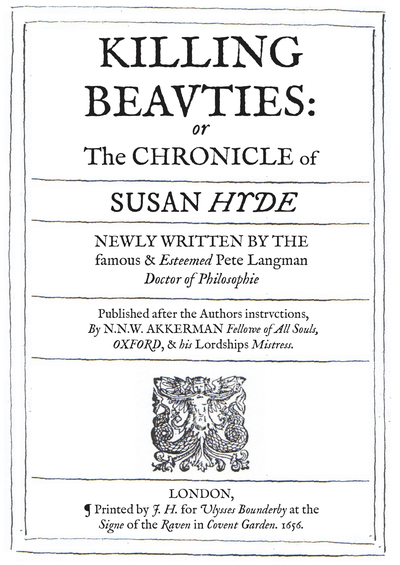

The idea of the female spy has attracted writers and dramatists over the years with its unbeatable combination of danger and sexual allure. Pete Langman comes to the party with his enjoyable new novel, Killing Beauties set in the England of 1655. Remember those old historical movies that began with a dramatic piece of text scrolling over the opening titles, giving us a lurid and enticing potted background to whatever we were about to watch? The blurb for Killing Beauties might say something like,

The idea of the female spy has attracted writers and dramatists over the years with its unbeatable combination of danger and sexual allure. Pete Langman comes to the party with his enjoyable new novel, Killing Beauties set in the England of 1655. Remember those old historical movies that began with a dramatic piece of text scrolling over the opening titles, giving us a lurid and enticing potted background to whatever we were about to watch? The blurb for Killing Beauties might say something like,  he beautiful woman is Susan Hyde, whose brother Sir Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon is principle advisor to the King in exile. With the aid of another young woman, Diane Jennings, Susan – and other members of the secret society known as Les Filles d’Ophelie – work with The Sealed Knot, coordinating underground Royalist activity in England and preparing for a general uprising against the Protectorate. Readers may be aware that the modern version of The Sealed Knot is a popular organisation of English Civil War re-enactors, but their historical namesakes were in deadly earnest, and organised two major rebellions before Charles II was finally crowned in 1661.

he beautiful woman is Susan Hyde, whose brother Sir Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon is principle advisor to the King in exile. With the aid of another young woman, Diane Jennings, Susan – and other members of the secret society known as Les Filles d’Ophelie – work with The Sealed Knot, coordinating underground Royalist activity in England and preparing for a general uprising against the Protectorate. Readers may be aware that the modern version of The Sealed Knot is a popular organisation of English Civil War re-enactors, but their historical namesakes were in deadly earnest, and organised two major rebellions before Charles II was finally crowned in 1661. In order to succeed in her mission, Susan must use the deadliest weapon at her disposal – her sexuality. The beneficiary of her attention is none other than John Thurloe himself. Thurloe is a fascinating historical figure, and has featured in several other novels, most notably in the Thomas Challoner series by Susanna Gregory, and in the SG MacLean’s Seeker stories. I reviewed MacLean’s

In order to succeed in her mission, Susan must use the deadliest weapon at her disposal – her sexuality. The beneficiary of her attention is none other than John Thurloe himself. Thurloe is a fascinating historical figure, and has featured in several other novels, most notably in the Thomas Challoner series by Susanna Gregory, and in the SG MacLean’s Seeker stories. I reviewed MacLean’s  ne of the problems facing writers of historical fiction is how to handle dialogue. We know how they wrote to each other in letters, but what were conversations like? Despite one or two of his characters occasionally lapsing into more recent vernacular, Langman negotiates this particular minefield successfully. Killing Beauties is an engaging and well researched piece of costume drama acted out on a turbulent and dangerous stage. It is published by Unbound

ne of the problems facing writers of historical fiction is how to handle dialogue. We know how they wrote to each other in letters, but what were conversations like? Despite one or two of his characters occasionally lapsing into more recent vernacular, Langman negotiates this particular minefield successfully. Killing Beauties is an engaging and well researched piece of costume drama acted out on a turbulent and dangerous stage. It is published by Unbound

s she gazes up at her bedroom ceiling, Lily Bell daydreams of becoming an actress. She is, to be sure, beautiful enough, with her long almost-white blond hair and her flawless complexion, but for the stepdaughter of a struggling artist in the London of 1851, her dreams of becoming Ophelia, Juliet or Desdemona are just foolish fantasies. Until the day her penniless stepfather receives a visit from one of his creditors, a mysterious self-styled Professor – Erasmus Salt. Salt is actually a theatrical showman, with a macabre interest in that overwhelming Victorian obsession, communicating with the dead. He offers Alfred Bell respite from the debt in return for Lily accompanying Salt and his spinster sister Faye to become the star of a new production, in which he will convince audiences that he has raised the dead.

s she gazes up at her bedroom ceiling, Lily Bell daydreams of becoming an actress. She is, to be sure, beautiful enough, with her long almost-white blond hair and her flawless complexion, but for the stepdaughter of a struggling artist in the London of 1851, her dreams of becoming Ophelia, Juliet or Desdemona are just foolish fantasies. Until the day her penniless stepfather receives a visit from one of his creditors, a mysterious self-styled Professor – Erasmus Salt. Salt is actually a theatrical showman, with a macabre interest in that overwhelming Victorian obsession, communicating with the dead. He offers Alfred Bell respite from the debt in return for Lily accompanying Salt and his spinster sister Faye to become the star of a new production, in which he will convince audiences that he has raised the dead. Despite her misgivings, Lily is intrigued by what appears to be a chance to achieve her ambition. After all, Salt’s theatrical illusion may be faintly sinister, but who knows what career doors it might unlock? Bell, despite the tears and misgivings of his wife, cannot get Lily out of the door fast enough, and soon the girl is on her way south, to the seaside town of Ramsgate, where Salt’s production is due to be presented at The New Tivoli theatre.

Despite her misgivings, Lily is intrigued by what appears to be a chance to achieve her ambition. After all, Salt’s theatrical illusion may be faintly sinister, but who knows what career doors it might unlock? Bell, despite the tears and misgivings of his wife, cannot get Lily out of the door fast enough, and soon the girl is on her way south, to the seaside town of Ramsgate, where Salt’s production is due to be presented at The New Tivoli theatre. y now we, as readers, know much more about Salt than does the hapless Lily. Having experience a terrible trauma in his youth, the balance of his mind has been disturbed; he may also be a murderer, and his obsession with the dead could be leading further than simply the creation of a melodramatic theatrical illusion.

y now we, as readers, know much more about Salt than does the hapless Lily. Having experience a terrible trauma in his youth, the balance of his mind has been disturbed; he may also be a murderer, and his obsession with the dead could be leading further than simply the creation of a melodramatic theatrical illusion.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle. One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master.

One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master. hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her.

hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her. ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly.

ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly. Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

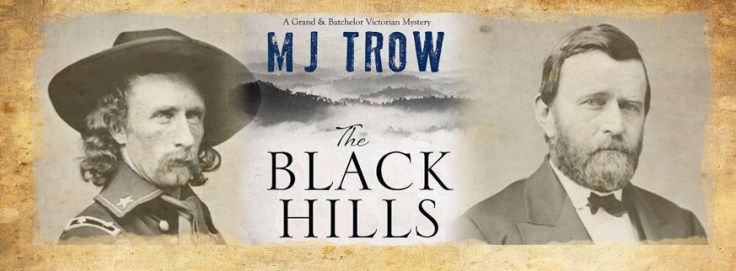

e may not have been the first to do so, but George MacDonald Fraser entertained many of us with the idea of writing novels where we get to meet actual key players from history. His archetypal bounder Harry Flashman, himself nicked from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, rubbed shoulders and crossed swords with a variety of celebrities, including Otto von Bismarck, Abraham Lincoln, and Emperor Franz Joseph. The late Philip Kerr narrowed things down as he introduced us to Heinrich Himmler, Reinhardt Heydrich and Joseph Goebbels in his Bernie Gunther novels.

e may not have been the first to do so, but George MacDonald Fraser entertained many of us with the idea of writing novels where we get to meet actual key players from history. His archetypal bounder Harry Flashman, himself nicked from Tom Brown’s Schooldays, rubbed shoulders and crossed swords with a variety of celebrities, including Otto von Bismarck, Abraham Lincoln, and Emperor Franz Joseph. The late Philip Kerr narrowed things down as he introduced us to Heinrich Himmler, Reinhardt Heydrich and Joseph Goebbels in his Bernie Gunther novels. One of the enjoyable conceits of the series is the comparison of how the two men behave when out of their cultural comfort zone. Grand is no gnarled backwoodsman, as his parents are wealthy New Hampshire patricians, but there is generally more fun to be had when Batchelor is trying to navigate the social niceties – or lack of them – in America. Trow, like MacDonald Fraser and Kerr, is a shameless name-dropper and we are not many pages into The Black Hills before we have bumped into George Armstrong Custer and broken into The White House to have a conversation with its current occupant, Ulysses Simpson Grant.

One of the enjoyable conceits of the series is the comparison of how the two men behave when out of their cultural comfort zone. Grand is no gnarled backwoodsman, as his parents are wealthy New Hampshire patricians, but there is generally more fun to be had when Batchelor is trying to navigate the social niceties – or lack of them – in America. Trow, like MacDonald Fraser and Kerr, is a shameless name-dropper and we are not many pages into The Black Hills before we have bumped into George Armstrong Custer and broken into The White House to have a conversation with its current occupant, Ulysses Simpson Grant. I readily put my hand up. When I read the words The Black Hills, the first image that flashed before my eyes was that of Doris Day in her buckskins and with her blonde bob under a troopers’ hat. Yes, my age is showing, but the 1953 film Calamity Jane starring Doris Day in the title role featured great songs like The Deadwood Stage, Secret Love and The Black Hills of Dakota. Trow is pretty much of my generation. He was a couple of years behind me at a minor public school (but don’t hold that against either of us). Never one to miss a trick, he features Calamity Jane in The Black Hills but, my oh my, Doris Day she ain’t. Short, pug-ugly and a stranger to personal hygiene, Jane Cannery is a fixture at Fort Abraham Lincoln. She is rarely sober and earns her living by washing the long johns of the Seventh Cavalry men who guard the frontier. She is notoriously quick on the draw with her Navy Colt, and the soldiers take care to give her a wide berth when she is in one of her moods.

I readily put my hand up. When I read the words The Black Hills, the first image that flashed before my eyes was that of Doris Day in her buckskins and with her blonde bob under a troopers’ hat. Yes, my age is showing, but the 1953 film Calamity Jane starring Doris Day in the title role featured great songs like The Deadwood Stage, Secret Love and The Black Hills of Dakota. Trow is pretty much of my generation. He was a couple of years behind me at a minor public school (but don’t hold that against either of us). Never one to miss a trick, he features Calamity Jane in The Black Hills but, my oh my, Doris Day she ain’t. Short, pug-ugly and a stranger to personal hygiene, Jane Cannery is a fixture at Fort Abraham Lincoln. She is rarely sober and earns her living by washing the long johns of the Seventh Cavalry men who guard the frontier. She is notoriously quick on the draw with her Navy Colt, and the soldiers take care to give her a wide berth when she is in one of her moods.

t was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Britain had anything like an organised police force. The Hocus Girl is set well before that time, and even a developing community like Leeds relied largely on local Constables and The Watch – both institutions being badly paid, unsupported and mostly staffed by elderly individuals who would dodder a mile to avoid any form of trouble or confrontation. There were, however, men known as Thieftakers. The title is self-explanatory. They were men who knew how to handle themselves. They were employed privately, and were outside of the rudimentary criminal justice system.

t was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Britain had anything like an organised police force. The Hocus Girl is set well before that time, and even a developing community like Leeds relied largely on local Constables and The Watch – both institutions being badly paid, unsupported and mostly staffed by elderly individuals who would dodder a mile to avoid any form of trouble or confrontation. There were, however, men known as Thieftakers. The title is self-explanatory. They were men who knew how to handle themselves. They were employed privately, and were outside of the rudimentary criminal justice system. Such a man is Simon Westow. He is paid, cash in hand, to recover stolen goods, by whatever means necessary. His home town of Leeds is changing at an alarming rate as mechanised cloth mills replace the cottage weavers, and send smoke belching into the sky and chemicals into the rivers. We first met Westow in The Hanging Psalm, and there we were also introduced to young woman called Jane. She is a reject, a loner, and she is also prone to what we now call self-harm. She is a girl of the streets, but not in a sexual way; she knows every nook, cranny, and ginnel of the city; as she shrugs herself into her shawl, she can become invisible and anonymous. Her sixth sense for recognising danger and her capacity for violence – usually via a wickedly honed knife – makes her an invaluable ally to Westow. I have spent many enjoyable hours reading the author’s books, and it is my view that Jane is the darkest and most complex character he has created. In many ways The Hocus Girl is all about her.

Such a man is Simon Westow. He is paid, cash in hand, to recover stolen goods, by whatever means necessary. His home town of Leeds is changing at an alarming rate as mechanised cloth mills replace the cottage weavers, and send smoke belching into the sky and chemicals into the rivers. We first met Westow in The Hanging Psalm, and there we were also introduced to young woman called Jane. She is a reject, a loner, and she is also prone to what we now call self-harm. She is a girl of the streets, but not in a sexual way; she knows every nook, cranny, and ginnel of the city; as she shrugs herself into her shawl, she can become invisible and anonymous. Her sixth sense for recognising danger and her capacity for violence – usually via a wickedly honed knife – makes her an invaluable ally to Westow. I have spent many enjoyable hours reading the author’s books, and it is my view that Jane is the darkest and most complex character he has created. In many ways The Hocus Girl is all about her. he 1820s were a time of great domestic upheaval in Britain. The industrial revolution was in its infancy but was already turning society on its head. The establishment was wary of challenge, and when Davey Ashton, a Leeds man with revolutionary ideas is arrested, Simon Westow – a long time friend – comes to his aid. As Ashton languishes in the filthy cell beneath Leeds Moot Hall, Westow discovers that he is treading new ground – political conspiracy and the work of an agent provocateur.

he 1820s were a time of great domestic upheaval in Britain. The industrial revolution was in its infancy but was already turning society on its head. The establishment was wary of challenge, and when Davey Ashton, a Leeds man with revolutionary ideas is arrested, Simon Westow – a long time friend – comes to his aid. As Ashton languishes in the filthy cell beneath Leeds Moot Hall, Westow discovers that he is treading new ground – political conspiracy and the work of an agent provocateur.

fter her success with

fter her success with  Zosha Nash (left), formerly Head of Development at The Foundling Museum explained, the care and love bestowed on the children was remarkable, even by modern standards. Their life expectancy exceeded that of many children at the time, and all were taught to read and write. The hospital was also famously associated with Handel, and it was in the chapel that Messiah was performed for the first time in England

Zosha Nash (left), formerly Head of Development at The Foundling Museum explained, the care and love bestowed on the children was remarkable, even by modern standards. Their life expectancy exceeded that of many children at the time, and all were taught to read and write. The hospital was also famously associated with Handel, and it was in the chapel that Messiah was performed for the first time in England

ix years after leaving her, Bess Bright returns to claim her daughter, to be greeting with the shattering news that Clara is no longer there. She has been claimed – just a day after Bess left her – by a woman correctly identifying the child’s token, a piece of scrimshaw, half a heart engraved with letters. The authorities are baffled, but convinced that a major fraud has been perpetrated. Bess’s shock turns to a passionate determination to find Clara.

ix years after leaving her, Bess Bright returns to claim her daughter, to be greeting with the shattering news that Clara is no longer there. She has been claimed – just a day after Bess left her – by a woman correctly identifying the child’s token, a piece of scrimshaw, half a heart engraved with letters. The authorities are baffled, but convinced that a major fraud has been perpetrated. Bess’s shock turns to a passionate determination to find Clara.