This is a welcome return for my favourite crime solving partnership in current fiction – 1960s Brighton reporter Colin Crampton and his delightful Australian girlfriend Shirley Goldsmith. Shirley discovers via an enigmatic letter – promising unidentified riches – that a long lost relative, Hobart Birtwhistle, has fetched up in the delightfully named Sussex village of Muddles Green, just a short spin away from Brighton in Colin’s rakish MGB. Unfortunately, when the couple arrive at half-uncle Hobart’s cottage, any avuncular reunion is prevented by the fact that the old chap is dead in his study chair, with a nasty head wound and throttle marks around his throat.

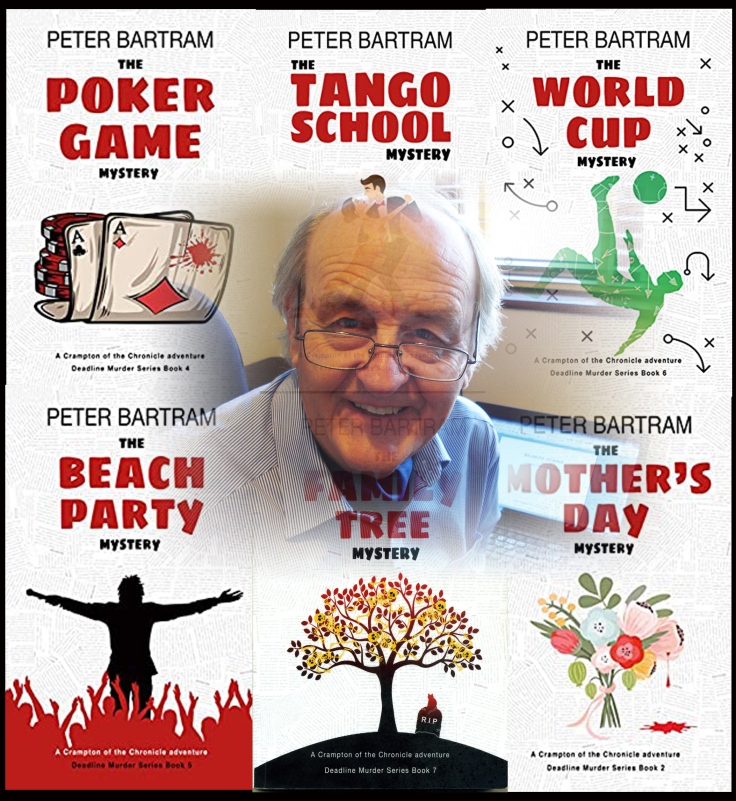

Colin and Shirley conduct their own investigation into Hobart’s murder and, as ever, it takes them far and wide, involving – amongst others – a tetchy history don with expertise in Australia’s gold rush, an eccentric Scottish lord and a team of women cricketers, not forgetting a most improbable but highly entertaining encounter with Ronnie Kray. Peter Bartram (perhaps an older real life version of Colin Crampton) never strays far away from the bedrock of these mysteries – the smoky offices and noisy print rooms of the Evening Chronicle. Crampton’s boss – the editor, Frank Figgis, perpetually wreathed in a haze of Woodbines smoke, also has a job for his chief crime reporter. Figgis, foe reasons of his own, has written a memoir, almost certainly full of dirty secrets featuring colleagues and bosses. But it has gone missing. Has the befuddled Figgis mislaid it, or has it been stolen? Figgis makes it clear that the recovery of the missing ‘blockbuster’ is to be Crampton’s chief focus.

Unfortunately, the killing of Hobart Birtwhistle is not the last in a fatal sequence that seems connected with the complex genealogy of Shirley’s obscure relatives – and a huge gold nugget discovered back in the day in Australia. Thanks to the research of the Scottish aristocrat (the real life Arthur ‘Boofy’ Gore), Shirley learns something that may well prove to be ‘to her advantage’, but may also put her name to the top of the killer’s list.

Former journalists do not always have the required skills to write good novels. Penning a 1000 word front page exclusive is not the same as writing a 300 page book. Novel readers need to be engaged long term – they don’t have the option of switching to the sports news on the back pages. Peter Bartram makes the transition with no apparent effort – he retains his journalist’s skill of boiling a narrative down to its essentials, while fleshing out the story with delightful characterisation and period detail.

Bartram’s genius lies partly in not taking himself too seriously as he tugs at our nostalgic heartstrings by recreating an impeccably convincing mid-1960s milieu, but – more potently – in having created two utterly adorable main characters who, if we couldn’t actually be them, we would at least love to have known them. At my age, current events beyond my control make me daily more choleric, and wishing for the days of common sense and decency, long since gone. But then I can retreat into a beautiful book like this, and be taken back to a kinder time, a time I understood and felt part of.

The Family Tree Mystery is published by The Bartram Partnership, and is available now. For more information on the Crampton of The Chronicle novels, click the image below.

It is 1965 and we are basking in the slightly faded grandeur of Brighton, on the south coast of England. The town has never quite recovered from its association, more than a century earlier, with the bloated decadence of The Prince Regent, and it shrugs its shoulders at the more recent notoriety bestowed by a certain crime novel brought to life on the big screen in 1947. Brighton has its present-day misdeeds too, and who better to write about it than the intrepid crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle, Colin Crampton?

It is 1965 and we are basking in the slightly faded grandeur of Brighton, on the south coast of England. The town has never quite recovered from its association, more than a century earlier, with the bloated decadence of The Prince Regent, and it shrugs its shoulders at the more recent notoriety bestowed by a certain crime novel brought to life on the big screen in 1947. Brighton has its present-day misdeeds too, and who better to write about it than the intrepid crime reporter for the Evening Chronicle, Colin Crampton? rampton is an enterprising and thoroughly likeable fellow, with a rather nice sports car and an even nicer girlfriend, in the very pleasing shape of Australian lass Shirley Goldsmith. Crampton is summoned to the office of his deputy editor Frank Figgis and, barely discernible amid the wreaths of smoke from his Woodbines, Figgis’s face is creased by more worry lines than usual. His problem? The Chronicle’s drama correspondent, Sidney Pinker, has been served with a libel writ for savaging, in print, a local theatrical agent called Daniel Bernstein.

rampton is an enterprising and thoroughly likeable fellow, with a rather nice sports car and an even nicer girlfriend, in the very pleasing shape of Australian lass Shirley Goldsmith. Crampton is summoned to the office of his deputy editor Frank Figgis and, barely discernible amid the wreaths of smoke from his Woodbines, Figgis’s face is creased by more worry lines than usual. His problem? The Chronicle’s drama correspondent, Sidney Pinker, has been served with a libel writ for savaging, in print, a local theatrical agent called Daniel Bernstein.

inker, by the way, is very much in the John Inman school of caricature luvvies, so those with an over-sensitive approach had better look away now. His pale green shirts, flowery cravats and patronage of certain Brighton nightspots are pure (politically incorrect) comedy.

inker, by the way, is very much in the John Inman school of caricature luvvies, so those with an over-sensitive approach had better look away now. His pale green shirts, flowery cravats and patronage of certain Brighton nightspots are pure (politically incorrect) comedy. Bernstein’s murder is seen as very much open-and-shut by the Brighton coppers, but Crampton does not believe that Pinker has the mettle to commit physical violence. Instead, his investigation takes him into the rather sad world of stand-up comedians. Today, our stand-up gagsters can become millionaire celebrities, but back in 1965, the old style joke tellers with their catchphrases and patter were becoming a thing of the past, as TV satire was breaking new ground and reaching new audiences. Crampton believes that the murder of Bernstein is connected to the agent’s former association with Max Miller and, crucially, the possession of Miller’s fabled Blue Book, said to contain all of The Cheeky Chappy’s best material – and a few jokes considered too rude for polite company.

Bernstein’s murder is seen as very much open-and-shut by the Brighton coppers, but Crampton does not believe that Pinker has the mettle to commit physical violence. Instead, his investigation takes him into the rather sad world of stand-up comedians. Today, our stand-up gagsters can become millionaire celebrities, but back in 1965, the old style joke tellers with their catchphrases and patter were becoming a thing of the past, as TV satire was breaking new ground and reaching new audiences. Crampton believes that the murder of Bernstein is connected to the agent’s former association with Max Miller and, crucially, the possession of Miller’s fabled Blue Book, said to contain all of The Cheeky Chappy’s best material – and a few jokes considered too rude for polite company. here have been occasions – and I am not alone – when I have used the term cosy in a book review, meaning no ill-will by it, but perhaps suggesting a certain lack of seriousness or an avoidance of the grim details of crime. Are the Colin Crampton books cosy? Perhaps.You will search in vain for explorations of the dark corners of the human psyche, any traces of bitterness or the consuming powers of grief and anger. What you will find is humour, clever plotting, a warm sense of nostalgia and – above all – an abundance of charm. A dictionary defines that word as “the power or quality of delighting, attracting, or fascinating others.” Remember, though, that the word has another meaning, that of an apparently insignificant trinket, but one which brings the wearer a sense of well-being and even, perhaps, the power to produce something magical.

here have been occasions – and I am not alone – when I have used the term cosy in a book review, meaning no ill-will by it, but perhaps suggesting a certain lack of seriousness or an avoidance of the grim details of crime. Are the Colin Crampton books cosy? Perhaps.You will search in vain for explorations of the dark corners of the human psyche, any traces of bitterness or the consuming powers of grief and anger. What you will find is humour, clever plotting, a warm sense of nostalgia and – above all – an abundance of charm. A dictionary defines that word as “the power or quality of delighting, attracting, or fascinating others.” Remember, though, that the word has another meaning, that of an apparently insignificant trinket, but one which brings the wearer a sense of well-being and even, perhaps, the power to produce something magical.

I have become a great fan of the Crampton of the Chronicle mysteries. Despite having multifarious murders and diverse dirty deeds, they are breezy, funny, beautifully written and they have a definite feel-good factor. Peter Bartram (left) is an old newspaper hand himself, and the background of a 1960s newsroom in a provincial newspaper is as authentic as it can get. Colin Crampton’s latest journey into the criminal underworld of Brighton is The Comedy Club Mystery. The cover blurb tells us:

I have become a great fan of the Crampton of the Chronicle mysteries. Despite having multifarious murders and diverse dirty deeds, they are breezy, funny, beautifully written and they have a definite feel-good factor. Peter Bartram (left) is an old newspaper hand himself, and the background of a 1960s newsroom in a provincial newspaper is as authentic as it can get. Colin Crampton’s latest journey into the criminal underworld of Brighton is The Comedy Club Mystery. The cover blurb tells us: “When theatrical agent Daniel Bernstein sues the Evening Chronicle for libel, crime reporter Colin Crampton is called in to sort out the problem.

“When theatrical agent Daniel Bernstein sues the Evening Chronicle for libel, crime reporter Colin Crampton is called in to sort out the problem.

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson.

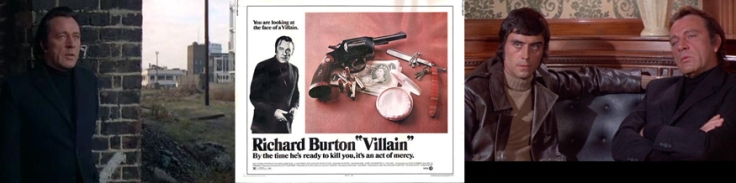

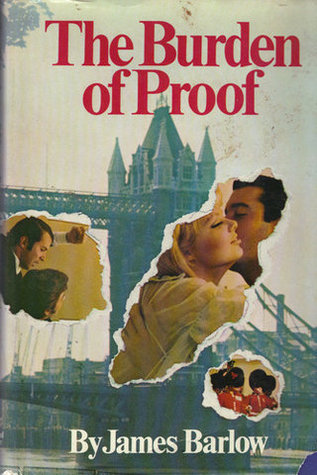

James Barlow was a Birmingham-born novelist who served as an air gunner with the RAF in WWII. Invalided out of service when he contracted tuberculosis, he faced a long convalescence. He began writing at this time, and after he worked in his native city as, of all things, a water rates inspector, he made the decision to write for a living. His first novel, The Protagonists, was published in 1956, but made little impact. It wasn’t until Term of Trial (1961) that he began to make a decent living from writing, and then more because film director Peter Glenville saw the cinematic potential in the story of an alcoholic school teacher whose career is threatened when he is accused of improper behaviour with a female pupil. The subsequent film had a star-studded cast including Sir Laurence Olivier, Simone Signoret, Sarah Miles, Terence Stamp, Hugh Griffith, Dudley Foster, Thora Hird and Alan Cuthbertson. Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

Term of Trial was a powerful and controversial film, but clearly had nothing to do with crime fiction. Barlow’s 1968 novel The Burden of Proof was another matter. By the time it was published, the Kray twins’ days as despotic rulers of London’s gangland were numbered. They were arrested on 8th May in that year and the rest, as they say, is history. The Burden of Proof is centred on a Ronnie Kray-style gangster, Vic Dakin. Dakin is psychotic homosexual, devoted equally to his dear old mum and a succession of pliant boyfriends, while finding time to be at the hub of a violent criminal network.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

In the city which is portrayed as little more than a moral sewer, we have the vile Dakin and his criminal associates; we have an earnest and incorruptible copper, Bob Matthews who Barlow sets up – along with Bob’s mild-mannered and decent wife Mary – as the apotheosis of what England used to be before the plague took hold. We have Gerald Draycott, a dishonest and manipulative MP who flirts with the dangerous world of gambling clubs, casinos, girls-for-hire and drugs-for-sale, but still dreams of becoming a cabinet minister.

I have a close friend who keeps himself fit by walking London suburbs searching charity shops for rare – and sometimes valuable – crime novels. On one particular occasion he was spectacularly successful with a rare John le Carré first edition, but he is ever alert to particular fads and enthusiasms of mine. Since I “discovered” PM Hubbard, thanks to a tip-off from none other than

I have a close friend who keeps himself fit by walking London suburbs searching charity shops for rare – and sometimes valuable – crime novels. On one particular occasion he was spectacularly successful with a rare John le Carré first edition, but he is ever alert to particular fads and enthusiasms of mine. Since I “discovered” PM Hubbard, thanks to a tip-off from none other than  Seldom, however, can a treasure have been protected by two more menacing guardians in Aunt Elizabeth and her maid-of-all-work Coster. Remember Blind Pew, one of the more terrifying villains of literature? Remember Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and the decades that it was hidden from sight? With a freedom that simply would not escape the censor today, Hubbard (right) taps into our visceral fear of abnormality and disability. Hubbard has created two terrifying women and a dog which is makes Conan Doyles celebrated hound Best In Show. The dog first:

Seldom, however, can a treasure have been protected by two more menacing guardians in Aunt Elizabeth and her maid-of-all-work Coster. Remember Blind Pew, one of the more terrifying villains of literature? Remember Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and the decades that it was hidden from sight? With a freedom that simply would not escape the censor today, Hubbard (right) taps into our visceral fear of abnormality and disability. Hubbard has created two terrifying women and a dog which is makes Conan Doyles celebrated hound Best In Show. The dog first:

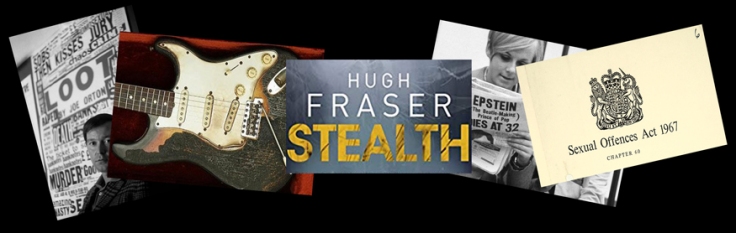

It is 1964, and Alec Douglas-Home’s Conservative government is on its last legs. The sex scandals which brought down his predecessor Harold Macmillan may have faded, but another one threatens to be just as explosive. Holborne is persuaded to defend a teenage boy accused of murdering one of the Krays’ stooges, but the fact that the youngster is what we would now call a rent boy sees Holborne accused of bringing his chambers into disrepute.

It is 1964, and Alec Douglas-Home’s Conservative government is on its last legs. The sex scandals which brought down his predecessor Harold Macmillan may have faded, but another one threatens to be just as explosive. Holborne is persuaded to defend a teenage boy accused of murdering one of the Krays’ stooges, but the fact that the youngster is what we would now call a rent boy sees Holborne accused of bringing his chambers into disrepute. Charles Holborne is a powerful and attractive central figure, but he is far from perfect. His chaotic private life reveals both passion and weakness. His judgement of human character also leaves something to be desired, as Simon Michael (right) shows, with a delicious and unexpected plot twist in the final pages of the novel. Corrupted is published by Urbane Publications

Charles Holborne is a powerful and attractive central figure, but he is far from perfect. His chaotic private life reveals both passion and weakness. His judgement of human character also leaves something to be desired, as Simon Michael (right) shows, with a delicious and unexpected plot twist in the final pages of the novel. Corrupted is published by Urbane Publications

Colin’s day has already been bad enough. He has been summoned to the office of Frank Figgis, the News Editor, and given a daunting task. The newspaper’s Editor, Pope by name (dubbed “His Holiness”, naturally) has a brother called Gervaise. Gervaise is in trouble. He has been mixing with some rather unsavoury characters, namely the adherents of Sir Oscar Maundsley, the aristocratic former fascist leader. Interned by Churchill during the war, he now dreams of Making Britain Great Again.

Colin’s day has already been bad enough. He has been summoned to the office of Frank Figgis, the News Editor, and given a daunting task. The newspaper’s Editor, Pope by name (dubbed “His Holiness”, naturally) has a brother called Gervaise. Gervaise is in trouble. He has been mixing with some rather unsavoury characters, namely the adherents of Sir Oscar Maundsley, the aristocratic former fascist leader. Interned by Churchill during the war, he now dreams of Making Britain Great Again.