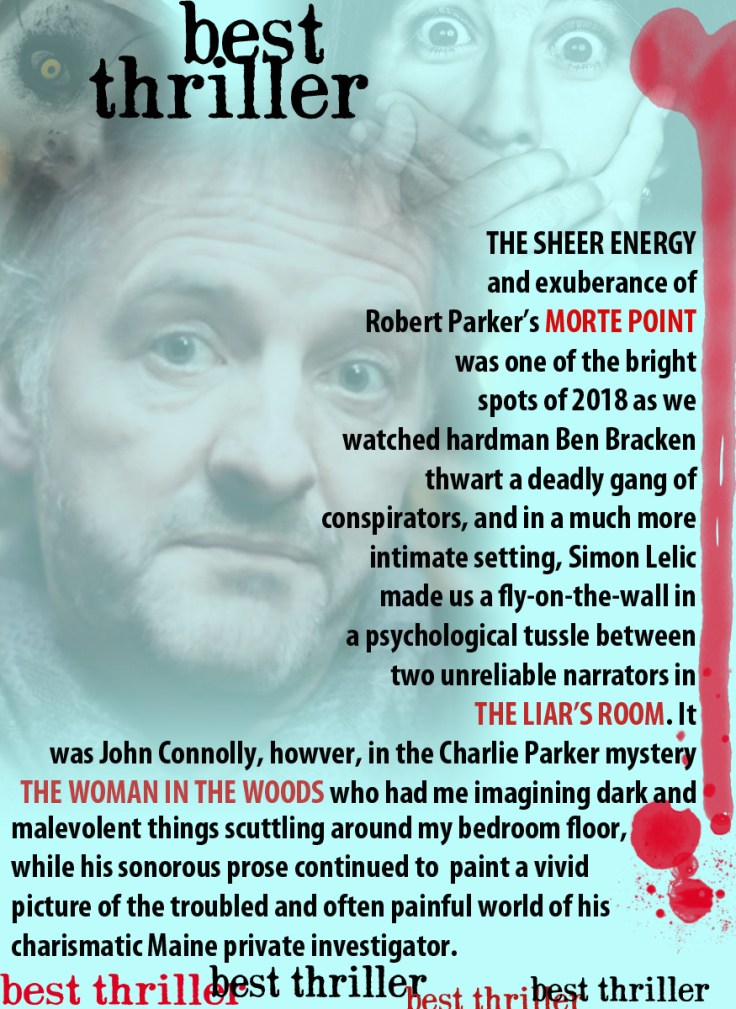

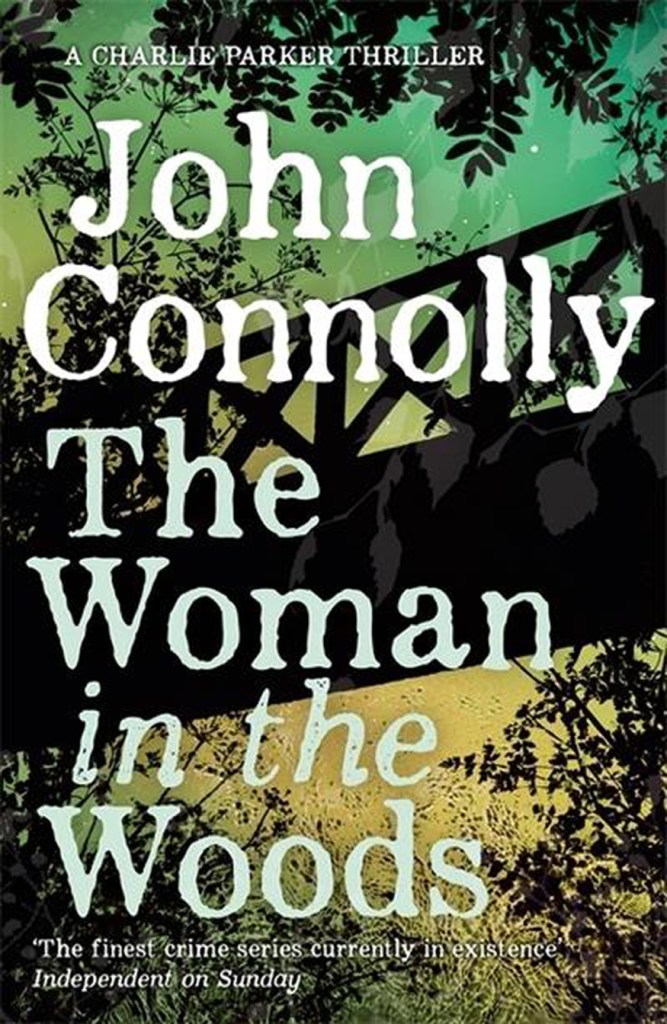

For more detail about why The Woman In The Woods is the Fully Booked Best Thriller 2018, click on the link: https://fullybooked2017.com/2018/04/17/the-woman-in-the-woods-between-the-covers/

AT THE APPROPRIATELY NAMED DEAD DOLLS HOUSE in Islington, the inventive folks at publishers Bonnier Zaffre launched Stacy Halls’ novel The Familiars with not so much a flourish as a brilliant visual fanfare.

AT THE APPROPRIATELY NAMED DEAD DOLLS HOUSE in Islington, the inventive folks at publishers Bonnier Zaffre launched Stacy Halls’ novel The Familiars with not so much a flourish as a brilliant visual fanfare.

The novel was at the centre of a vigorous bidding war and, having won it, Bonnier Zaffre celebrated in style. The book is set in seventeenth century Lancashire, and the drama plays out under the lowering and forbidding bulk of Pendle Hill. If that rings a bell, then so it should. The Pendle Witch Trials were a notorious example of superstition and bigotry overwhelming justice. Ten supposed witches were found guilty and executed by hanging.

Stacey Halls takes the real life character of Fleetwood Shuttleworth, still a teenager, yet mistress of the forbidding Gawthorpe Hall. Despite being only 17, she has suffered multiple miscarriages, but is pregnant again. When a young midwife, Alice Grey, promises her a safe delivery, the two women – from such contrasting backgrounds – are drawn into a dangerous social upheaval where a thoughtless word can lead to the scaffold.

Back to modern London. Francesca Russell, now Publicity Director at Bonnier Zaffre, has masterminded many a good book launch, and she and her colleagues were on song at The Dead Dolls House. We were able to mix our own  witchy tinctures using a potent combination of various precious oils. I went for Frankincense with a dash of Patchouli. I managed to smear it everywhere and such was its potency that my wife was convinced that I had been somewhere less innocent than a book launch.

witchy tinctures using a potent combination of various precious oils. I went for Frankincense with a dash of Patchouli. I managed to smear it everywhere and such was its potency that my wife was convinced that I had been somewhere less innocent than a book launch.

We were encouraged to give a nod to the novel’s title, and draw a picture of our own particular familiar, and pin it to a board for all to see. I decided to buck the trend towards foxes, cats and toads, and went for a fairly liberal interpretation of that modern icon, the spoilt and decidedly bratty Ms Peppa Pig.

The absolute highlight and masterstroke of the evening was, however, a brief dramatisation of a scene from the novel. Gemma Tubbs was austere and elegant as Fleetwood, while Amy Bullock, with her Vermeer-like simple beauty, brought Alice to life.

That’s the good news, and I have a copy of the novel. The bad news is that it isn’t out on general release until February 2019. Here’s wishing everyone a happy winter, and I hope you all survive another one. If you need an incentive to get through the long hours of cold, darkness and northern gloom, The Familiars should fit the bill. It will be published by Bonnier Zaffre and can be pre-ordered here.

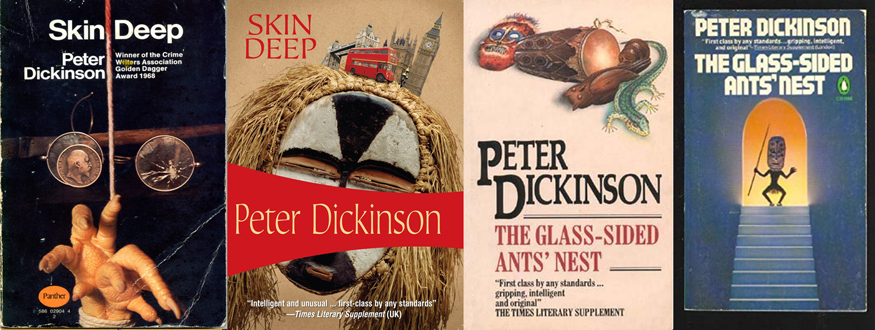

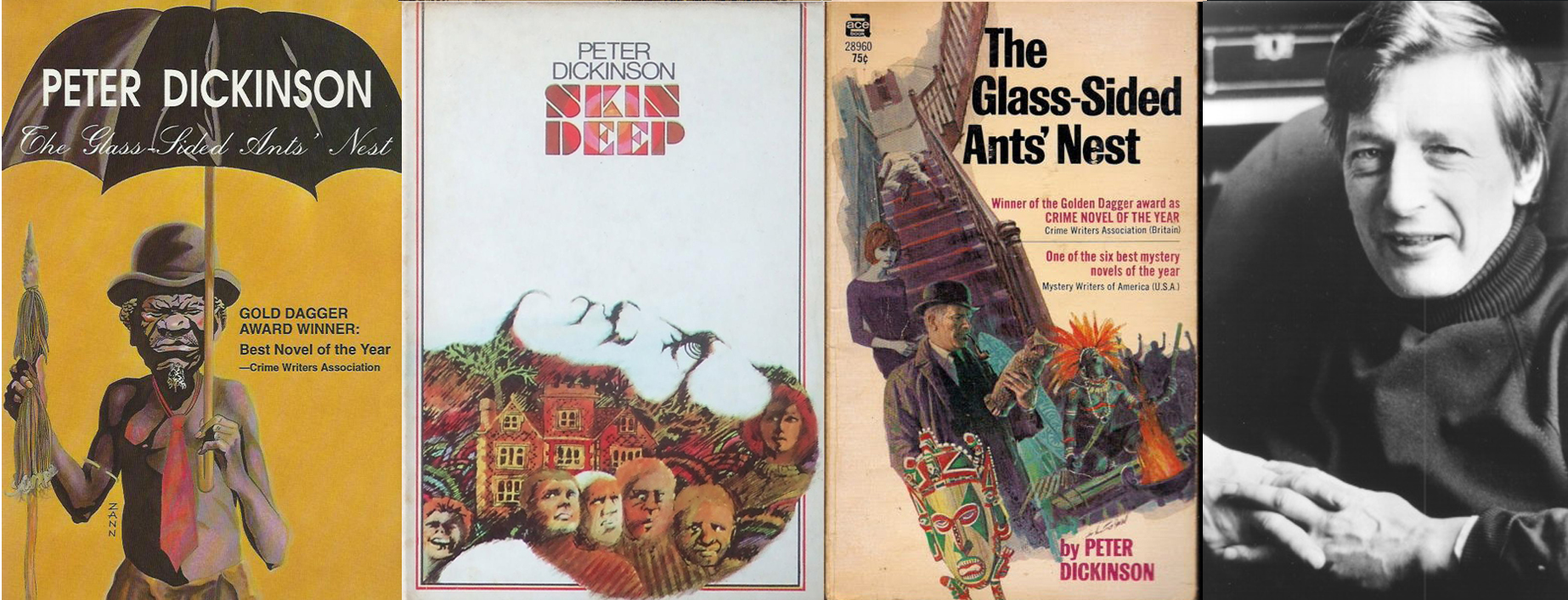

In June 1968 USA publishers Harper & Row released a book titled The Glass Sided Ants’ Nest. The novel, by Peter Malcolm de Brissac Dickinson, aka Peter Dickinson, was simultaneously published in Britain by Hodder & Stoughton as Skin Deep and won a CWA Gold Dagger in that year. Both titles are still available

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir Derek Raymond, who was there from 1944 until 1948.

Incidentally, I don’t think there are many Old Etonian authors around these days, but Dickinson (left) was there from 1941 to 1946, and it is tempting to wonder if he ever rubbed shoulders in those years with another Eton scholar by the name of Robert William Arthur Cook, better known to us as the Godfather of English Noir Derek Raymond, who was there from 1944 until 1948.

Skin Deep introduces us to London copper, Superintendent Jimmy Pibble, who was to feature in several subsequent mysteries. Already, Dickinson sets out his stall. Writers more ready to twang the purse strings of the book buying public might name their hero something more suggestive of intrigue and danger, like Jack Powers, Max Stead, Dan Ruger, Will Stark or Tom Caine. But Jimmy Pibble? He sounds more like a walk-on player in a Carry On film. But this, we soon learn, is Dickinson’s little joke, perhaps at the expense of lesser writers or less demanding readers. Pibble is highly intelligent, sensitive, but no-one’s pushover and, despite several bitterly ironic turns of events, nothing in the story is played for laughs.

The stage set of Skin Deep is brilliantly bizarre. Even the modern maestro of wonderfully eccentric plots, the Right Honorable Member for King’s Cross, Mr Christopher Fowler, might have baulked at this one. In a sturdily-built but nondescript London suburb, Flagg Terrace, live the exiled sole survivors of an ancient New Guinean tribe, the Kus. They survived a massacre by Japanese invaders in 1943 and have relocated to London. These folk, some crippled by genetic ailments, have transformed their home into a strange replica of their home village. The men lead separate lives from the women, and they practice a religion which is a perplexing blend of missionary Christianity and their native beliefs. Flagg Terrace has not been gentrifird:

“The tide of money had washed around it. The hordes of conquering young executives, sweeping down like Visigoths from the east and driving the cowering and sullen aboriginals into the remoter slums of Acton, had left it alone. Neither taste nor wealth could assail its inherent dreadfulness.”

When Aaron, the leader of the Ku folk, is found dead, battered to death with a carved wooden owl, Pibble is given the task of discovering the killer. He is clearly regarded by his more conventional superiors as a good copper, but something of an oddball, and someone to be kept as away as possible from high profile cases.

To say that the Kus are an odd lot is an understatement. Among the residents are Dr Eve Ku, a distinguished anthropologist. She is married to Paul Ku, but she can only be referred to as ‘he’ due to her countryfolk’s distinctive take on gender politics. Robin Ku is, on the one hand a rather clever teenager who has an alter-ego as a Ku drummer, beating the traditional slit drums as an accompaniment to sexually charged tribal rituals. Add into the mix Bob Caine, a neighbour of the Ku’s. He is what John Betjeman called “a thumping great crook”, but he is a sinister fraudster who was not only implicated in the Japanese destruction of the Ku people, but has serious connections to organised crime in the here-and-now.

Skin Deep is a wonderful example of literary crime fiction in which the author doesn’t write down to his audience, but skillfully uses language to evoke mood, ambience and atmosphere. Dickinson’s ear for dialogue is attuned to the slightest inflection so that we instantly know how is talking, without the need for clumsy prompts. Jimmy Pibble is a delightful character with a gentle streak of misanthropy in his soul. His idea of a good pub is:

“…a back street nook kept by a silent old man who lived for the quality of his draught beer. It would be empty when Pibble used it, save for two genial dotards playing dominoes.”

Pibble’s view of the policeman’s lot is similarly sanguine:

“That was the whole trouble with police work. You come plunging in, a jagged Stone Age knife, to probe the delicate tissues of people’s relationships, and of course you destroy far more than you discover. And even what you discover will never be the same as it was before you came; the nubbly scars of your passage will remain.”

Don’t be misled into thinking that there is anything remotely Golden Age or cosy about this book. It is often darkly reflective, and Aaron’s killer is both unmasked and punished in one tragic moment of unfortunate misjudgment by Jimmy Pibble. There were to be five more novels featuring the distinctive detective:

A Pride of Heroes (1969); US: The Old English Peep-Show

The Seals (1970); US: The Sinful Stones

Sleep and His Brother (1971)

The Lizard in the Cup (1972)

One Foot in the Grave (1979)

Peter Dickinson was also a successful and widely admired author of children’s books. He died in 2015 at the age of 88. Click the link to read an obituary.

Something we do all too rarely on Fully Booked, mea culpa, is to feature articles and reviews by guest writers. I am delighted that an old mate of mine, Stuart Radmore (we go back to the then-down-at-heel Melbourne suburbs of Carlton and Parkville in the 1970s, where he was a law student and I was teaching art at Wesley College) has written this feature on a writer who, as an individual, never actually existed. Stuart’s knowledge of crime fiction is immense, and so I will let him take up the story.

Something we do all too rarely on Fully Booked, mea culpa, is to feature articles and reviews by guest writers. I am delighted that an old mate of mine, Stuart Radmore (we go back to the then-down-at-heel Melbourne suburbs of Carlton and Parkville in the 1970s, where he was a law student and I was teaching art at Wesley College) has written this feature on a writer who, as an individual, never actually existed. Stuart’s knowledge of crime fiction is immense, and so I will let him take up the story.

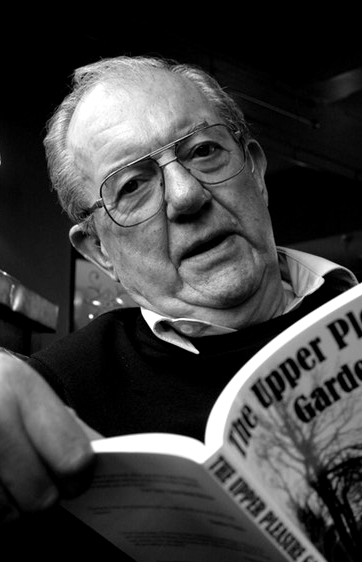

P.B Yuill was the transparent alias of Gordon Williams and Terry Venables, who in the early to mid 1970s wrote a number of novels together. Gordon Williams (1934-2017) and pictured below, started out as a straight novelist, but over time would turn his hand to almost anything literary – thrillers, SF screenplays, even ghosted footballer’s memoirs. Terry Venables (b. 1943) was at this time described as “top football star already worth over £150,000 in transfer fees”.

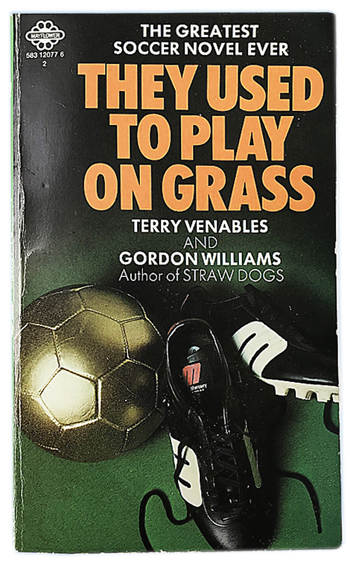

Their first joint outing (published under their own names) was They Used To Play On Grass (1971). Described, not incorrectly, on the paperback cover as “the greatest soccer novel ever”, it’s still an enjoyable read, with each man’s contribution being pretty obvious.

Their first joint outing (published under their own names) was They Used To Play On Grass (1971). Described, not incorrectly, on the paperback cover as “the greatest soccer novel ever”, it’s still an enjoyable read, with each man’s contribution being pretty obvious.

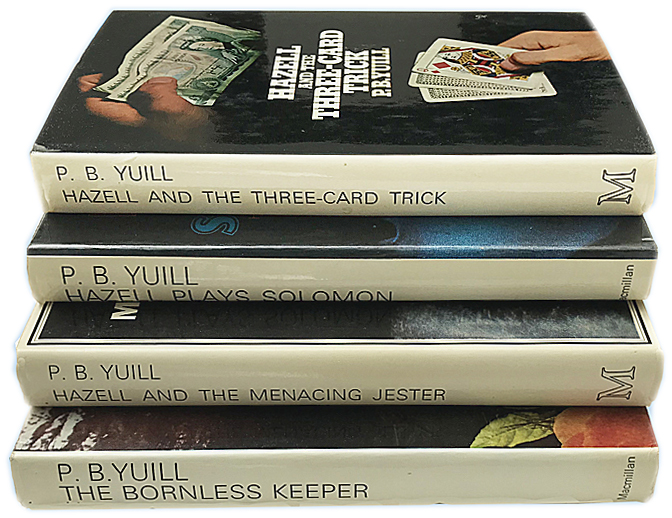

Next up was The Bornless Keeper (1974), published under the name of PB Yuill. A credible horror/thriller, set in modern times.

“Peacock Island lies just off the English south coast. But it could belong to an earlier century; its secret overgrown coverts, its strange historic legends are maintained and hidden by the rich old lady who lives there as a recluse.”.

If the tale now seems overfamiliar – the moody locals, the over-inquisitive visiting film crew, the one person who won’t be told not to go out alone – it’s partly because these elements, perhaps corny even then, have been over-used in too many slasher movies since. Although credited to P.B Yuill, the setting and theme of the novel reads as the work of Gordon Williams alone

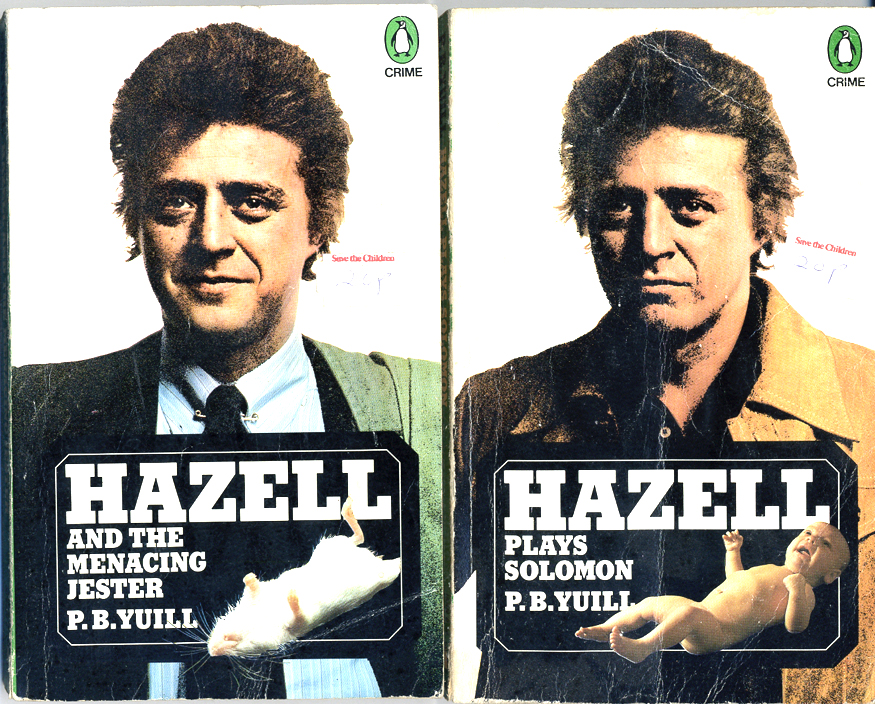

Now to Hazell. There are three Hazell novels, published by Macmillan in 1974, ’75 and ’76 – Hazell Plays Solomon, Hazell and the Three Card Trick, and Hazell and the Menacing Jester.

The premise of the first novel is original; James Hazell, ex-copper and self-described “biggest bastard who ever pushed your bell button” is hired by a London woman, now wealthy and living in the US, to confirm her suspicion that her child was switched for another shortly after its birth in an East London maternity hospital. Clearly, there can be no happy ending to such enquiries, and the story leads to dark places and deep secrets.

The next two novels are a little lighter in tone, but still deal with the grittier side of London life. In Three Card Trick a man has apparently suicided by jumping in front of a Tube train. His widow doesn’t accept this – there is the insurance to consider – and hires Hazell to prove her right.

In Menacing Jester we are on slightly more familiar PI ground; a millionaire and his wife are apparently the victims of a practical joker. Or is there something more sinister behind it?

All three novels contain plenty of sex, violence and local colour – card sharps, clip joint hostesses, Soho drinking dens – and the authors were clearly familiar with the more picturesque aspects of the London underworld and portray these with energy and humour. Readers looking for evidence of the “casual racism/sexism/whatever” of the 1970s will not come away empty-handed.

The authors were keen to develop the Hazell character into a possible TV series, and the later two books seem to be written with this in mind. This duly came to pass, via Thames Television, and the first series was broadcast in 1978, starring Nicholas Ball as a youthful James Hazell. Gordon Williams, with Venables (right) and other writers, was responsible for a number of the episodes (including ‘Hazell Plays Solomon’), and it remains a very watchable series. The second, and final, series broadcast in 1979/80 was not so successful. The hardness was gone, Hazell and Inspector ‘Choc’ Minty had become something of a double act and, while not outright comedy, it came close at times. It’s not surprising to learn that Leon Griffiths, one of the second series screenwriters, went on to create and develop the very successful series Minder later that year.

The authors were keen to develop the Hazell character into a possible TV series, and the later two books seem to be written with this in mind. This duly came to pass, via Thames Television, and the first series was broadcast in 1978, starring Nicholas Ball as a youthful James Hazell. Gordon Williams, with Venables (right) and other writers, was responsible for a number of the episodes (including ‘Hazell Plays Solomon’), and it remains a very watchable series. The second, and final, series broadcast in 1979/80 was not so successful. The hardness was gone, Hazell and Inspector ‘Choc’ Minty had become something of a double act and, while not outright comedy, it came close at times. It’s not surprising to learn that Leon Griffiths, one of the second series screenwriters, went on to create and develop the very successful series Minder later that year.

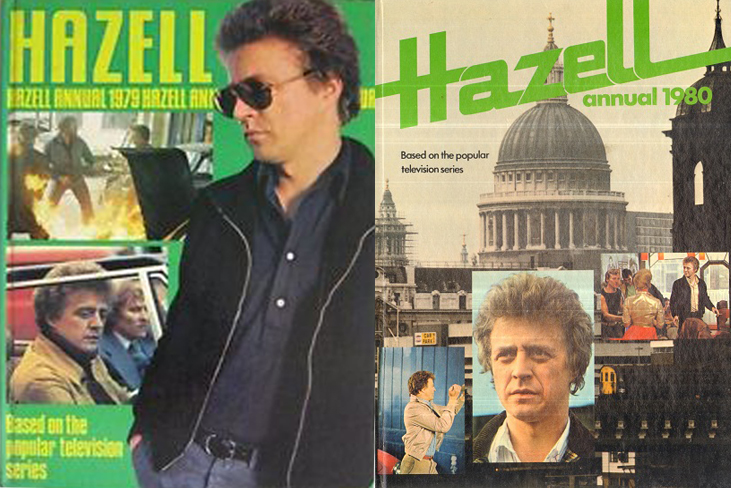

And that was about it. But there was to be a last hurrah for Hazell in print. Two Hazell annuals, “based on the popular television series”, appeared in 1978 and 1979. The tales in these books are surprisingly tough, bearing in mind the intended teenage readership. Hazell’s adventures are told via short stories and comic strips, and include strong-ish violence, blackmail and other criminality. While the contribution of “P. B Yuill” was probably nil, the stories are true to the feel of the first series of the TV programme.

To conclude: English fictional private eyes are a rare breed, and fewer still can claim to have begun as a literary, rather than television, creation. Hazell is among the best of these. The three novels rightly remain in print, and are eminently readable.

There is a postscript. There was one last appearance of P.B Yuill. In early 1981 ‘Arena’, a BBC2 documentary series, devoted a programme to the attempts of Williams and Venables to write a new Hazell adventure – tentatively entitled ‘Hazell and the Floating Voter’ – and it featured such worthies as John Bindon and Michael Elphick playing the part of Hazell. It’s never been broadcast since, and while it was pleasing to see the authors discussing the character of Hazell, in retrospect the programme seems like an excuse for a few days’ drinking on licence-payers’ money.