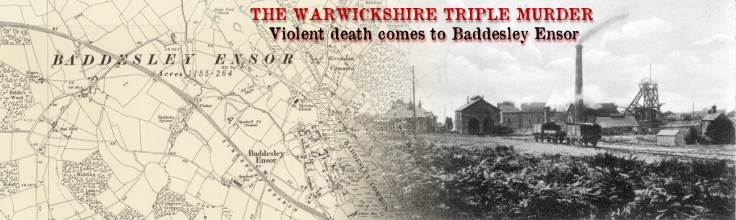

SO FAR: It is Sunday 24th August 1902, and in the colliery village of Badley Ensor, the Chetwynd family live on Watling Street Road. The household consists of widow Eliza Chetwynd (62) her son Joseph (24) daughter Eliza (21) and Eliza’s eleven week old son, who had not yet been named. The baby’s father, George Place (29) also lives there, but there is a tense atmosphere, as Place had just been served with am Affiliation Summons, which made him legally responsible for the upkeep of the child.

The events of that fateful Sunday morning were reported thus in a local newspaper:

Late on Saturday evening, after leaving a public-house in Wilnecote, Place told two men that he intended to do for the three of them (meaning the women and the child), and showed the men a six-chambered revolver and a packet of cartridges. He got to his lodgings shortly after midnight, and it was a curious circumstance that at ten minutes past one in the morning Mrs. Chetwynd saw a neighbour, Mrs. Shilton, and told her she was afraid Place was going to do something to them, for he had a revolver and had got a knife to open a packet of cartridges.

Late on Saturday evening, after leaving a public-house in Wilnecote, Place told two men that he intended to do for the three of them (meaning the women and the child), and showed the men a six-chambered revolver and a packet of cartridges. He got to his lodgings shortly after midnight, and it was a curious circumstance that at ten minutes past one in the morning Mrs. Chetwynd saw a neighbour, Mrs. Shilton, and told her she was afraid Place was going to do something to them, for he had a revolver and had got a knife to open a packet of cartridges.

The four rooms of the house were all occupied. The victims slept together in one bed in the room the right on the ground floor; the kitchen on the same floor was occupied by the son of Mrs. Chetwynd, who slept on a sofa ; Place slept in one room on the upper floor; and Jesse Chetwynd, another son of Mrs. Chetwynd, with his wife, who had come from Upper Baddesley for the night, used the other room.

At about a quarter to six in the morning Place came downstairs and entering the room where the women and child were asleep, deliberately shot each of them through the head, the bullets entering the right side of the head. The baby was in its mother’s arms at the time. The older woman must have had her hand up to her head, for two of her fingers had been wounded by the bullet. Jesse Chetwynd rushed downstairs on hearing the reports, and found Place sitting on the doorstep with the revolver in his hand. Place had neither hat nor jacket on. Jesse Chetwynd said to him ” Whatever have you been doing ” but Place made no reply.

The other son, Joseph, said Place had threatened him. and that Jesse’s coming down saved him from being shot. The poor old woman and the child died almost immediately, but the daughter lay unconscious for about four hours, when she succumbed. The old lady was heard to exclaim “Oh !” when Mrs. Jackson, a neighbour, went in. The murderer walked, away quietly from the scene of the tragedy. He took the the public road to Atherstone, and was followed by Samuel Shilton, whom gave up the revolver and 14 cartridges. On the way, Place said to Shilton, ” If you hadn’t come after me I would been comfortable at the bottom of the canal.”

The rest of this grim tale almost tells itself. George Place, apparently unrepentant throughout, was taken through the usual procedure of Coroner’s inquest, Magistrates’ court, and then sent to the Autumn Assizes at Warwick in December. Presiding over the court was Richard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, and the trial was brief. Despite the obligatory plea from Place’s defence team that he was insane when he pulled the trigger three times in that Baddesely Ensor cottage, the jury were having none of it, and the judge donned the black cap, sentencing George Place to death by hanging. The trial was at the beginning of December, the date fixed for the execution was fixed for 13th December, but George Place did not meet his maker until 30th December. It is idle to speculate about quite what kind of Christmas Place spent in his condemned cell, but for some reason, during his incarceration, he had converted to Roman Catholicism. It seems he left this world with more dignity than he had allowed his three victims. The executioner was Henry Pierrepoint.

The rest of this grim tale almost tells itself. George Place, apparently unrepentant throughout, was taken through the usual procedure of Coroner’s inquest, Magistrates’ court, and then sent to the Autumn Assizes at Warwick in December. Presiding over the court was Richard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, and the trial was brief. Despite the obligatory plea from Place’s defence team that he was insane when he pulled the trigger three times in that Baddesely Ensor cottage, the jury were having none of it, and the judge donned the black cap, sentencing George Place to death by hanging. The trial was at the beginning of December, the date fixed for the execution was fixed for 13th December, but George Place did not meet his maker until 30th December. It is idle to speculate about quite what kind of Christmas Place spent in his condemned cell, but for some reason, during his incarceration, he had converted to Roman Catholicism. It seems he left this world with more dignity than he had allowed his three victims. The executioner was Henry Pierrepoint.

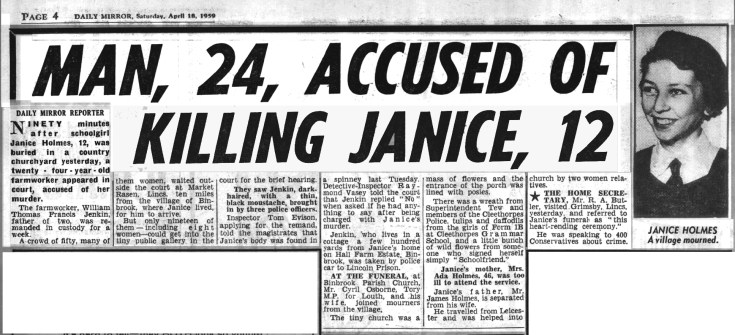

FOR MORE TRUE CRIME STORIES FROM WARWICKSHIRE, CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW

For those new to this wonderful series, here’s the back story. Enora Andressen is an actress in her early forties. She has won fame, if not fortune, by starring in what used to be known as ‘art films’ – often European produced and of a literary nature. She has a twenty-something son, Malo, the product of a one-night-fling with a former drug boss, Harold ‘H’ Prentice. ‘H’ and Enora have become reunited, after a fashion, but it is not a sexual relationship. In the previous novel, ‘H’ is stricken with Covid, and barely survives. That story is told in

For those new to this wonderful series, here’s the back story. Enora Andressen is an actress in her early forties. She has won fame, if not fortune, by starring in what used to be known as ‘art films’ – often European produced and of a literary nature. She has a twenty-something son, Malo, the product of a one-night-fling with a former drug boss, Harold ‘H’ Prentice. ‘H’ and Enora have become reunited, after a fashion, but it is not a sexual relationship. In the previous novel, ‘H’ is stricken with Covid, and barely survives. That story is told in

Central character Ronin Nash is a Scot who found himself in America, did a spell in the armed forces, and then worked as an FBI agent. When he is sidelined as a scapegoat in a kidnap case which went tragically wrong, he retreats to a lakeside log cabin hideaway, but is recruited by his former boss to join a new outfit, the Inter-agency Investigation Bureau. He is sent to the small town of Finchley in upstate New York to find out the investigate the discovery of three dead bodies in an abandoned mine just outside the town.

Central character Ronin Nash is a Scot who found himself in America, did a spell in the armed forces, and then worked as an FBI agent. When he is sidelined as a scapegoat in a kidnap case which went tragically wrong, he retreats to a lakeside log cabin hideaway, but is recruited by his former boss to join a new outfit, the Inter-agency Investigation Bureau. He is sent to the small town of Finchley in upstate New York to find out the investigate the discovery of three dead bodies in an abandoned mine just outside the town.  We learn pretty quickly that something is not quite right in Finchley, but Nash spots this, and realises he is being played. He is smart enough to let the players assume he is ignorant of what is going on and the only question in his mind is just how many of the Sheriff’s Department – and other significant townsfolk – are in on the secret.

We learn pretty quickly that something is not quite right in Finchley, but Nash spots this, and realises he is being played. He is smart enough to let the players assume he is ignorant of what is going on and the only question in his mind is just how many of the Sheriff’s Department – and other significant townsfolk – are in on the secret.

Domestic noir is often notable for the fact that police investigations only play a tiny part in the plots, with the author concentrating mainly on the nasty things that people who live on bland suburban estates do to each other. The latest novel from Lisa Jewell (left) is different, in that one of the central characters is London copper DCI Samuel Owusu, who takes charge of an investigation prompted by the discovery of a bag on human bones washed up on the Thames mud.

Domestic noir is often notable for the fact that police investigations only play a tiny part in the plots, with the author concentrating mainly on the nasty things that people who live on bland suburban estates do to each other. The latest novel from Lisa Jewell (left) is different, in that one of the central characters is London copper DCI Samuel Owusu, who takes charge of an investigation prompted by the discovery of a bag on human bones washed up on the Thames mud. Ask any book reviewer with children – or grandchildren – what is the most painful crime plot they have to read and, if they are anything like me, they will say the trope of missing (presumed murdered) children. Still, it happens all too often in real life, and so it remains a legitimate subject for crime fiction. Dublin writer Andrea Mara (right) takes a stab at this most difficult of subjects in Hide and Seek.

Ask any book reviewer with children – or grandchildren – what is the most painful crime plot they have to read and, if they are anything like me, they will say the trope of missing (presumed murdered) children. Still, it happens all too often in real life, and so it remains a legitimate subject for crime fiction. Dublin writer Andrea Mara (right) takes a stab at this most difficult of subjects in Hide and Seek.