SO FAR: Lincoln, May 1903. Sarah and Leonard Patchett have a troubled marriage. She works as a housekeeper in Lincoln, while he is a bricklayer in Gainsborough. At the end of May, he has traveled to Lincoln to see her. They have a daughter, Rachel, a few weeks short of her second birthday, and she lives with her mother at the house of John King in Spencer Street. Sarah is John King’s housekeeper. On the evening of Tuesday 26th May, Patchett has pleaded with his wife to come back to him, but she only agrees to walk with him to the railway station where he says he will catch a train back to Gainsborough.

After the evening of 26th May, Sarah Patchett is never seen alive again. The last sighting of her was recording in a court statement:

“Mr. J. H. Gadd, livery stable proprietor, stated that about seven o’clock on the night of Tuesday, May 26th, he was driving to his field in Boultham Lane in the company with one of his men. His man called his attention to a man and woman standing at the gate to the second field in Boultham Lane. The woman looked sad and distressed, and the man was in a leaning position with his foot on the lower bar of the gate. As he passed, the man turned round, and he caught full view of his face. On Saturday he identified the body the deceased as that of the woman saw the gate the previous evening.”

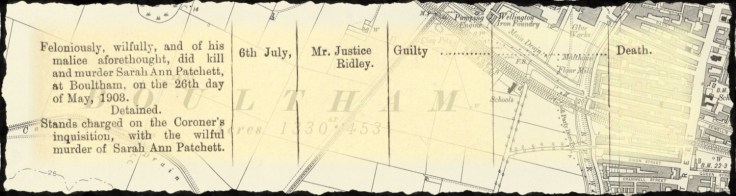

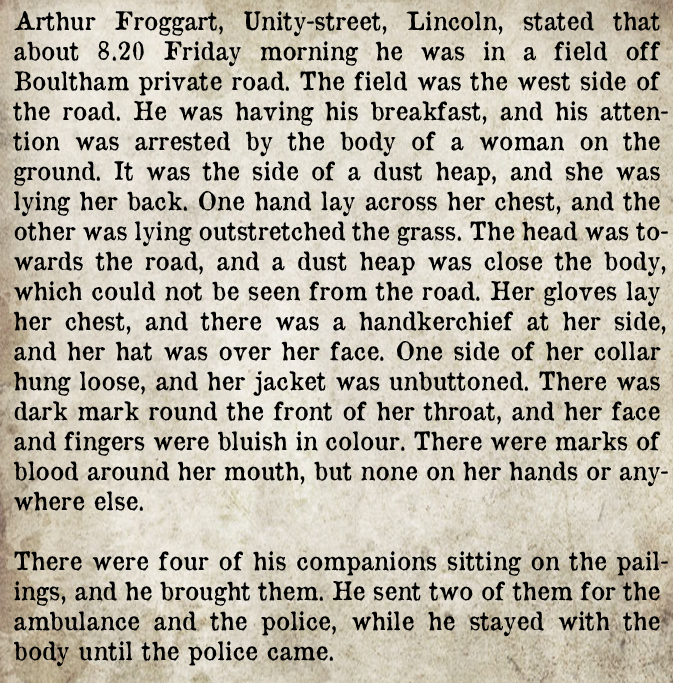

Sarah Patchett’s body was found in a field just west of the Boultham Park carriage road on the morning of 29th May. She had been strangled. When a coroner’s inquest was convened at Bracebridge, the details are still chilling over a century later:

It might be of interest to show where Sarah Patchett was murdered. As far as I can tell, her body was found about 100 yards from the Boultham Board School on the west side of what was then the private carriage road leading to Boultham Hall. Now, of course, the ground where her body lay for three days (red circle) is long since built over. The graphic below may be helpful.

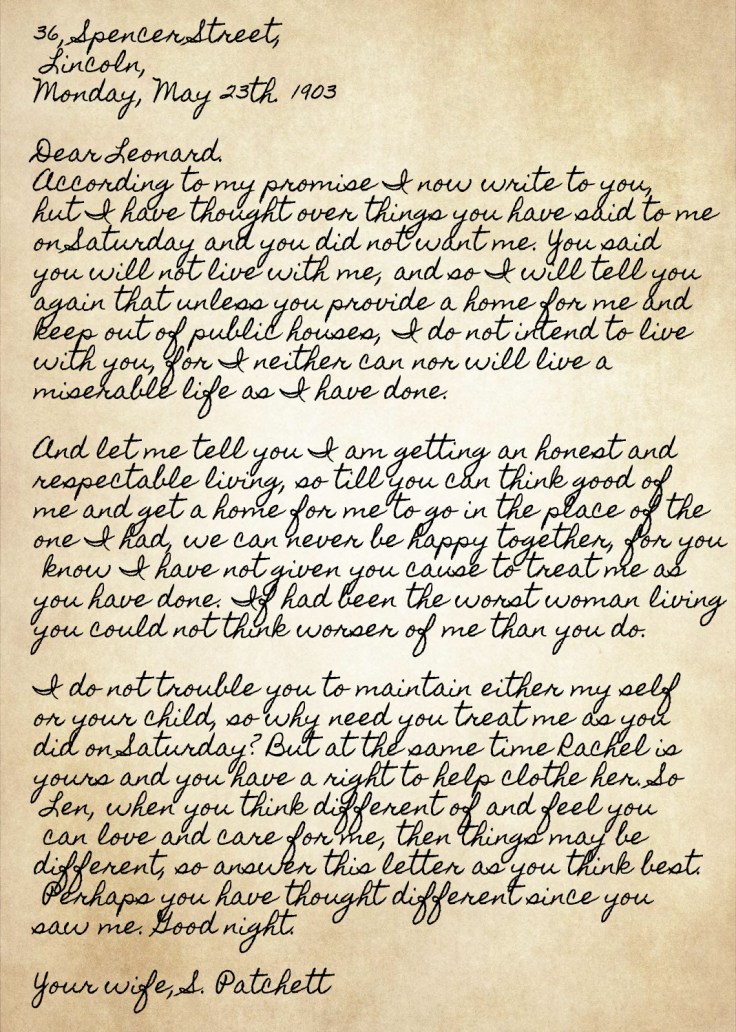

Leonard Patchett was arrested and held in custody. When he was searched, a letter from his wife was found in his jacket. I have made a facsimile (below)

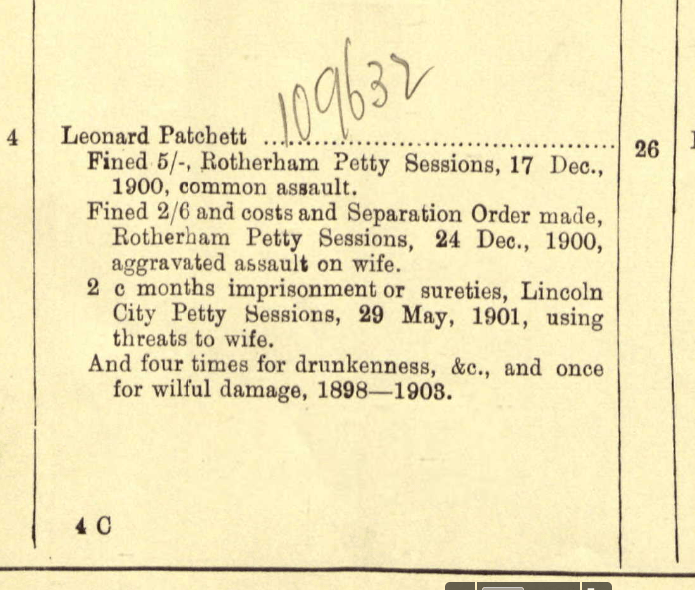

At the coroner’s inquest, the magistrates’ court and the subsequent Assizes at Lincoln, Patchett insisted he was innocent and, to be fair, the evidence against him was purely circumstantial. Unguarded remarks he made after his wife’s death painted a very different picture, however. When asked, back at the Gainsborough building site, if he was going up to work on the scaffold, he said, “The next scaffold I will be on will be the scaffold at Lincoln with a rope around my neck.”

What did he mean when he said to Mrs Iremonger, “I will have her before the night is out”? Did he mean he would come and take his daughter, Rachel, or was it a threat to the life of his wife ?

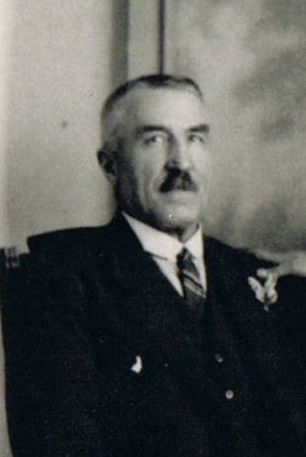

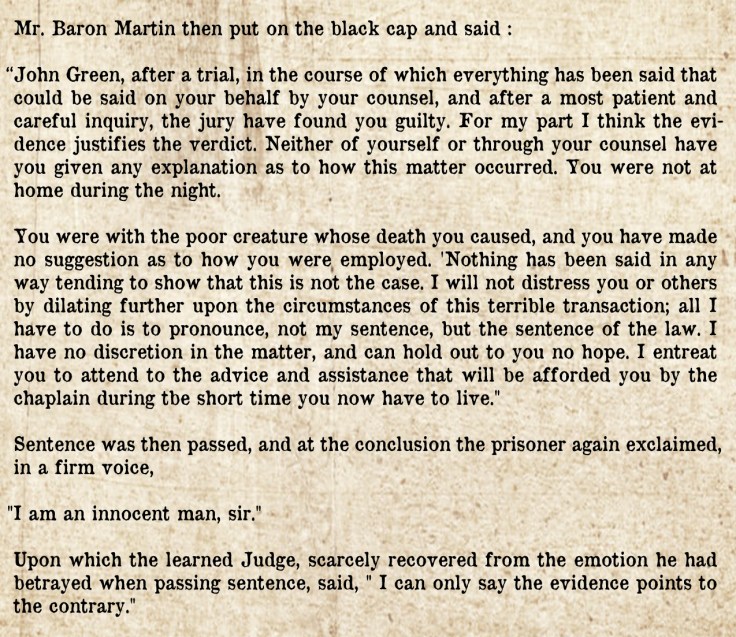

On Monday 6th July, Leonard Patchett was tried for murder at LIncoln, before Mr Justice Ridley (left). Patchett insisted he was innocent but the jury did not agree. The newspapers reported the inevitable conclusion:

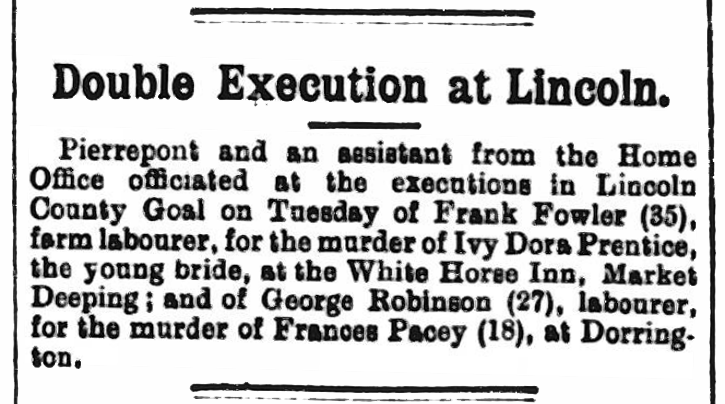

“The jury took twelve minutes to consider their decision, and returned into Court with a verdict of “Guilty.” The prisoner heard the sentence apparently unmoved, and in reply to the question as to whether he had anything to say why sentence of death should not passed, replied firmly: “No, but I am perfectly innocent.” The Judge then put on the black cap and said he was bound to agree with the verdict the jury had given. It had been clearly established that the prisoner’s was the hand that strangled the unfortunate woman. The judge recommended him to try to make his peace with Almighty God during the few days of life that remained to him. Sentence of death was then passed. Prisoner received the solemn sentence without the slightest feeling, and then calmly turned round, and walked down the steps to the cells. His sister, who was in an adjoining room, fainted on hearing the sentence. The execution will take place in Lincoln Gaol.”

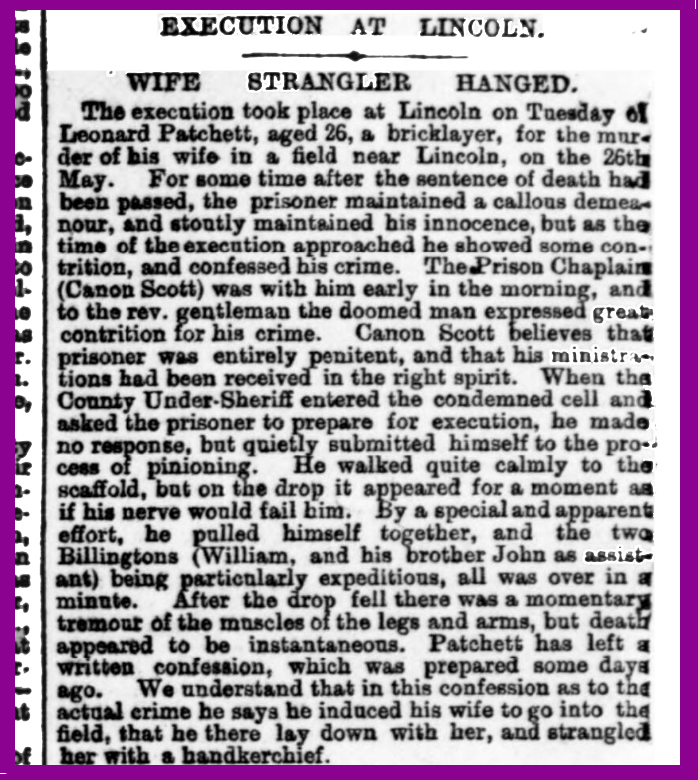

And so it did:

Sarah Ann Patchett was buried in Canwick Road cemetery, while the body of her husband joined those of other hanged murderers in the little graveyard within the walls of the Lucy Tower at Lincoln Castle. There is one link to this terrible tale which takes us into relatively recent times (albeit fifty years ago). Rachel Ceciia Patchett was raised in various children’s homes and, by then known as Rachel Patchett-Smith, married James Newman in 1934. She died in 1972, and was buried at St Peter’s, Pilning, Gloucestershire. My thank to Mandy Freeman for the information about Rachel.

FOR MORE LINCOLNSHIRE MURDER CASES, CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW

The plot hinges around a series of dire events in the life of Jo Howe’s boss, Detective Chief Superintendent Phil Cooke. Already trying to keep his mind on the job while his wife is dying of cancer, fate deals him another cruel blow when his son Harry, a promising professional footballer, is murdered, seemingly a casualty in a drug turf war. He steps down, but then comes into contact with a shadowy group of apparent vigilantes, who tell him that Harry was not the clean-cut sporting hero portrayed in the local media – he was heavily into performance enhancing drugs. The vigilantes – whose business plan is to provide a highly illegal alternative police force, where customers pay for the quick results that the Sussex Constabulary seem unable to provide – blackmail Phil into standing in the election of Police and Crime Commissioner. He is forced to agree, and is elected.

The plot hinges around a series of dire events in the life of Jo Howe’s boss, Detective Chief Superintendent Phil Cooke. Already trying to keep his mind on the job while his wife is dying of cancer, fate deals him another cruel blow when his son Harry, a promising professional footballer, is murdered, seemingly a casualty in a drug turf war. He steps down, but then comes into contact with a shadowy group of apparent vigilantes, who tell him that Harry was not the clean-cut sporting hero portrayed in the local media – he was heavily into performance enhancing drugs. The vigilantes – whose business plan is to provide a highly illegal alternative police force, where customers pay for the quick results that the Sussex Constabulary seem unable to provide – blackmail Phil into standing in the election of Police and Crime Commissioner. He is forced to agree, and is elected. Graham Bartlett (right) was a police officer for thirty years and mainly policed the city of Brighton and Hove, rising to become a Chief Superintendent and its police commander, so it is no accident that this is a grimly authentic police procedural. It is also very topical as, away from the violence and entertaining mayhem, it focuses on the seemingly insoluble problem of the divide between the public’s expectations of policing, and what the force is actually able – or willing – to deliver. Bartlett doesn’t over-politicise his story but, reading between the lines – and I may be mistaken – I suspect he may feel that, with ever more limited resources, the police should not be so keen to divert valuable time and resources away from their core job of catching criminals. My view. and it may not be his, is that effusive virtue signaling by police forces in support of this or that social justice trend does them – nor most of us – no favours at all.

Graham Bartlett (right) was a police officer for thirty years and mainly policed the city of Brighton and Hove, rising to become a Chief Superintendent and its police commander, so it is no accident that this is a grimly authentic police procedural. It is also very topical as, away from the violence and entertaining mayhem, it focuses on the seemingly insoluble problem of the divide between the public’s expectations of policing, and what the force is actually able – or willing – to deliver. Bartlett doesn’t over-politicise his story but, reading between the lines – and I may be mistaken – I suspect he may feel that, with ever more limited resources, the police should not be so keen to divert valuable time and resources away from their core job of catching criminals. My view. and it may not be his, is that effusive virtue signaling by police forces in support of this or that social justice trend does them – nor most of us – no favours at all.

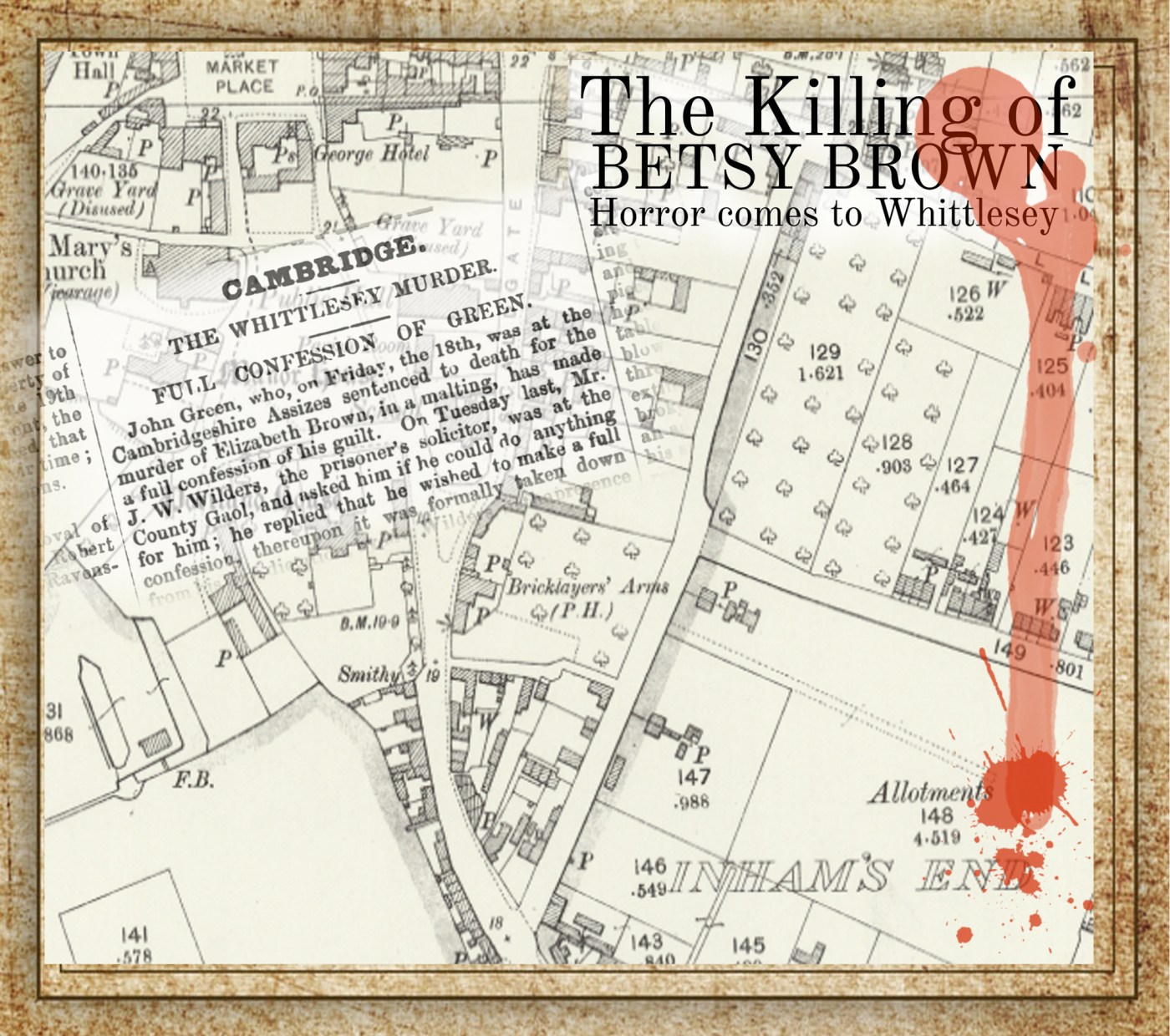

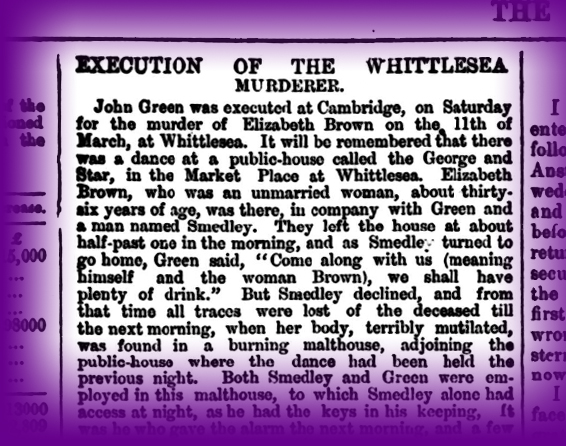

She (Brown) was at that time smoking a long pipe, and when we got into the furnace room, I drew a quart pitcher full of gin out of the bottle, and sat down on the settle and drank most of it, if not all of it, both of us smoking. We had sat down for half hour, when I wanted to have connection with her, but she would not. I pulled her off the settle. She kicked and knocked about, and got hold of my hair, and I tried and tried as long as I could to have connection with her, and when she would not, I hit her on the body with my fists, and she fell on the floor. I then kicked her on the body more than once. She did not scream out. I then felt so bad that I did not know what to do, as I felt I had killed her. I stooped down and got hold of her and shook her, and I found that she was really dead. I then drank hearty of some gin.

She (Brown) was at that time smoking a long pipe, and when we got into the furnace room, I drew a quart pitcher full of gin out of the bottle, and sat down on the settle and drank most of it, if not all of it, both of us smoking. We had sat down for half hour, when I wanted to have connection with her, but she would not. I pulled her off the settle. She kicked and knocked about, and got hold of my hair, and I tried and tried as long as I could to have connection with her, and when she would not, I hit her on the body with my fists, and she fell on the floor. I then kicked her on the body more than once. She did not scream out. I then felt so bad that I did not know what to do, as I felt I had killed her. I stooped down and got hold of her and shook her, and I found that she was really dead. I then drank hearty of some gin.

The presiding judge was Sir Samuel Martin QC (1801-1883), Anglo-Irish Baron of the Exchequer (left). The first thing he did was to dismiss all charges against William Smedley. He said:

The presiding judge was Sir Samuel Martin QC (1801-1883), Anglo-Irish Baron of the Exchequer (left). The first thing he did was to dismiss all charges against William Smedley. He said:

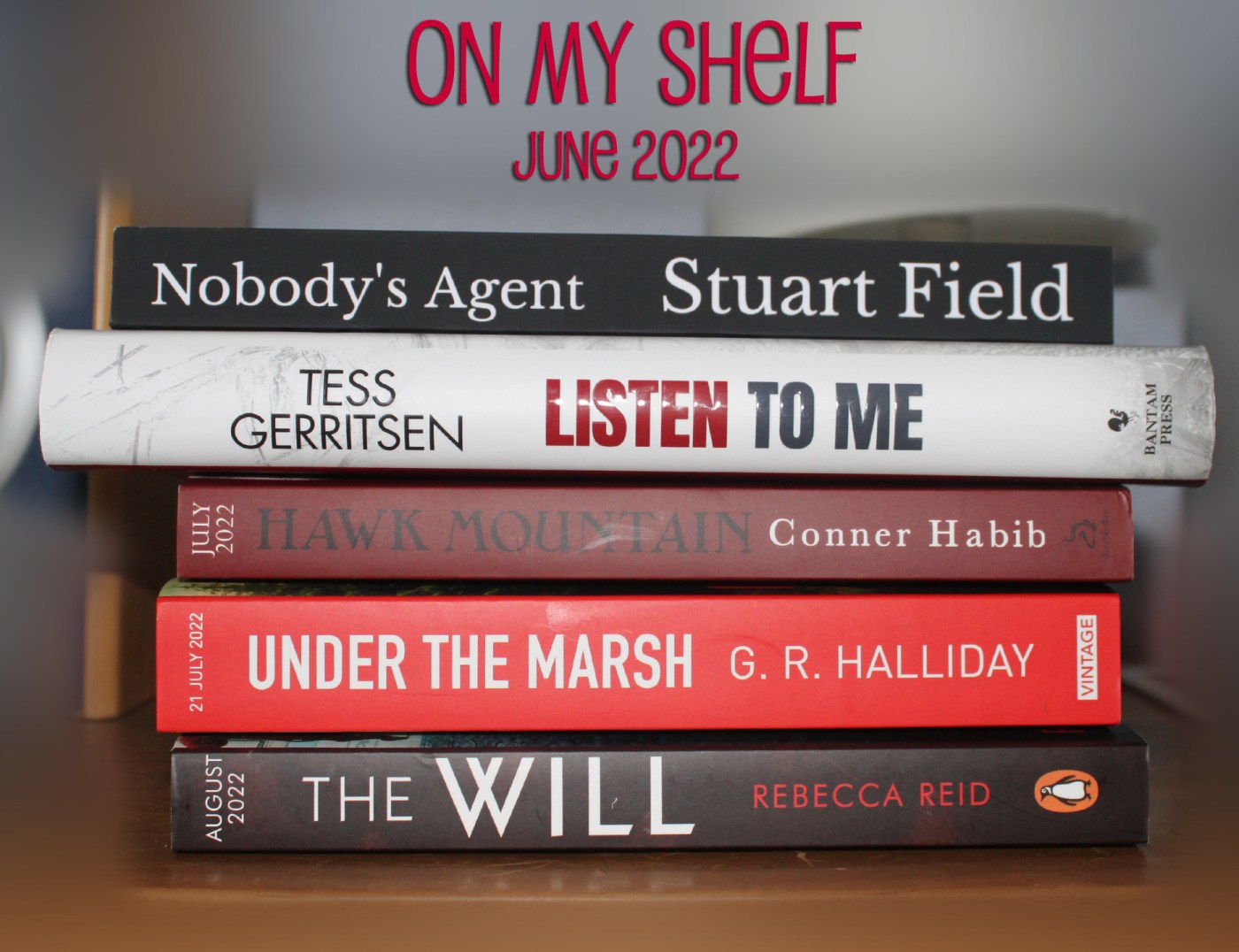

This thriller is set in Finchley – not Mrs Thatcher’s old baileywick but a fictional (I believe) small town in upstate New York, where three bodies are discovered in an old mine. The local Sheriff is out of his depth, and asks the FBI for help. They persuade a former agent, Ronin Nash to take the case, but he discovers the town has a big secret which powerful people will go to any lengths to protect. The author tells us:

This thriller is set in Finchley – not Mrs Thatcher’s old baileywick but a fictional (I believe) small town in upstate New York, where three bodies are discovered in an old mine. The local Sheriff is out of his depth, and asks the FBI for help. They persuade a former agent, Ronin Nash to take the case, but he discovers the town has a big secret which powerful people will go to any lengths to protect. The author tells us: Detective Jane Rizzoli

Detective Jane Rizzoli Described as a literary thriller, Hawk Mountain tells the story of a thirty-something man – Todd – who is accidentally re-united with his high school tormentor. The Jack of old seems to be a reformed character, warm, radiant and sorry for his youthful misdemeanours. But is he? And was the chance reunion accidental at all? Cue a spiral of menace and entrapment which plumbs the very worst parts of the human psyche. Perhaps I don’t get out as much as I should, but I think this is the first thriller written by a former adult movie performer. He says:

Described as a literary thriller, Hawk Mountain tells the story of a thirty-something man – Todd – who is accidentally re-united with his high school tormentor. The Jack of old seems to be a reformed character, warm, radiant and sorry for his youthful misdemeanours. But is he? And was the chance reunion accidental at all? Cue a spiral of menace and entrapment which plumbs the very worst parts of the human psyche. Perhaps I don’t get out as much as I should, but I think this is the first thriller written by a former adult movie performer. He says: I missed From The Shadows, the first book in the DI Monica Kennedy series, but thoroughly

I missed From The Shadows, the first book in the DI Monica Kennedy series, but thoroughly  ‘The Reading of the Will’ used to be a standard trope in crime fiction years ago. Picture the scene, preferably in black and white. The fusty old solicitor addresses the family, gathered in the library of a stately old house. What he announces sets up the plot of the novel/film, and pitches different family members against each other. Rebecca Reid revives this chestnut, and gives it a modern slant, when the family of the recently deceased Cecily Mordaunt gather in Norfolk at Roxborough Hall, each hoping to leave the scene as significant beneficiaries of the old lady. Of course there is disappointment and joy – which will lead to chicanery and revenge. Rebecca Reid is a freelance journalist. She graduated from Royal Holloway’s Creative Writing MA in 2015. She is the author of Perfect Liars, Truth Hurts, Two Wrongs and The Power of Rude. The Will is her latest book, and joins two of the other novels in this post in being published

‘The Reading of the Will’ used to be a standard trope in crime fiction years ago. Picture the scene, preferably in black and white. The fusty old solicitor addresses the family, gathered in the library of a stately old house. What he announces sets up the plot of the novel/film, and pitches different family members against each other. Rebecca Reid revives this chestnut, and gives it a modern slant, when the family of the recently deceased Cecily Mordaunt gather in Norfolk at Roxborough Hall, each hoping to leave the scene as significant beneficiaries of the old lady. Of course there is disappointment and joy – which will lead to chicanery and revenge. Rebecca Reid is a freelance journalist. She graduated from Royal Holloway’s Creative Writing MA in 2015. She is the author of Perfect Liars, Truth Hurts, Two Wrongs and The Power of Rude. The Will is her latest book, and joins two of the other novels in this post in being published