SO FAR: On the night of Saturday 3rd March 1907, In a drink-fueled fit of rage, 33 year-old Edwin James Moore has set his mother on fire at their home, 13 Oxford Street. She is pronounced dead at the scene.

While the doctor, police, neighbours and the other members of the Moore family crowded into 13 Oxford Street, what had become of the central character in this drama, Edwin James Moore? With skin hanging from his hands and arms after trying – and failing – to extinguish the flames that killed his mother, he was taken by one of the neighbours to a nearby chemist to have his burns dressed, but it was clear the damage was severe, and he was taken to the Warneford Hospital, was treated further treated for his wounds and kept in overnight.

In the drama of the moment, the cries of young Bertie Moore (“Help! Murder!”) had been temporarily disregarded, and it was assumed that there had been a terrible accident, but when the proverbial dust settled and Police Sergeant Rainbow spoke to the distressed child, it was clear that Fanny Moore’s death was something other than a misfortune. On the Sunday morning, Rainbow visited Edwin Moore in hospital, and put it to him that he had killed his mother. Moore replied, indignantly:

“No, never. I tried to put out the fire and burnt my coat in doing it.”

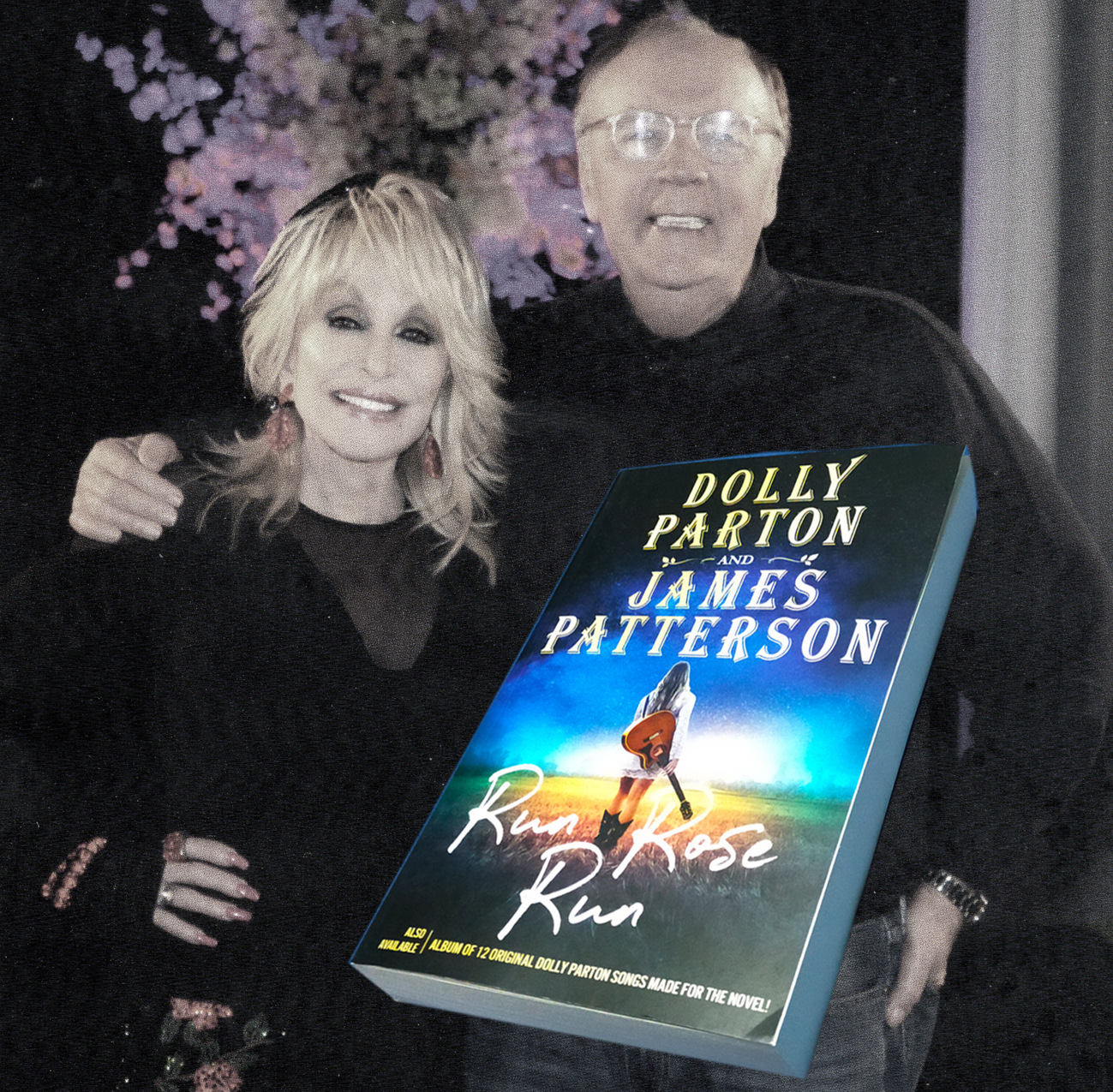

Despite his denial, Moore was arrested and appeared before Leamington magistrates, where he continued to deny that he had caused his mother’s death. The magistrates were unconvinced, and sent him to be tried at the next Warwick Assizes on a charge of wilful murder. Meanwhile, the Moore family had a final melancholy duty to perform.

The County Assizes were a major civic event. The Great and the Good put on their best finery to celebrate this most emphatic and visible reminder to the common folk that British justice was a solemn affair, and those who fell foul of it were in a very dark place indeed. The local paper reported:

“WARWICKSHIRE WINTER ASSIZES. The Warwickshire Winter Assizes were opened at the Shire Hall, Warwick, Friday morning, before Mr. Justice Phillimore. His Lordship arrived in the town on Thursday afternoon, and was met by the High Sheriff (Sir William Jaffray) and the Sheriff’s Chaplain (the Rev. J. Thompson;. GRAND JURY: the following were sworn upon the Grand Jury : Lord Algernon Percy foreman), Mr. H. Lakin, Mr F. E. Muntz, Major F. Hood Gregory, Capt. F. Gerard, Mr. D. S. Greig, Mr. F. Stanger Leathes, Major H. Chesshyre Molyneus, Major Gibsone, Major Armstrong, Mr A. Kay, Mr R. W. Lindsay, .Mr A. Sabin Smith, Mr. J. Booth, Mr. W. E. Everitt, G Anson-Yeld, Mr. E. C. Gray-Hatherell, Mr. A. Batchelor, Mr. Savory, Mr. P. S. Danby, Mr. S. Flavel and Captain K. Oliver-Bellasis.”

Percy, Lakin, Flavel – just three names that still resonate locally today, and several others who, if you Google them, remain clearly at the heart of the British establishment more than a century after they convened to decide the fate of Edwin James Moore. It is pointless to speculate whether a rough former soldier was ever going to get the benefit of the doubt after being accused of murdering the woman who brought him into the world and watched over him during his childhood. The jury system in 1907 was what it was. The trial was very brief, and on Monday 11th March Mr Justice Phillimore had little hesitation when he instructed the jury, who found Moore guilty of murder. Phillimore (left) donned the symbolic black cap, and sent Edwin James Moore back to his gloomy cell in Warwick Prison on Cape Road (below) to await the visit of the hangman.

In an age when the wheels of justice turned extremely slowly, the downfall of Edwin James Moore was extremely swift. By my reckoning, the interval between that fateful Saturday night and his death on the morning of 6th April, at the hands of (below, with newspaper report) John Ellis – whose day job was a newsagent and hairdresser in Rochdale – was just thirty-three days. To borrow the obligatory final words of the sentencing judge, “May God have mercy on his soul.”

Number 13 Oxford Street is a narrow three-story terraced house used these days, I believe, for student accommodation. It was advertised recently as a six bedroom let, a snip (!) at £3,360 pcm. The Bank of England inflation calculator tells me that in 1891, Edward Moore and his family would have been paying just under £26 a month. He had a large family comprising his wife Fanny Adelaide (36) and children Edwin James Moore (16), Fanny A Moore (14), William A Moore (13), Joseph C Moore (11), Rose Hannah Moore (10), Percy E Moore (8), Leonard J Moore (7) and Ernest F Moore (4).

Number 13 Oxford Street is a narrow three-story terraced house used these days, I believe, for student accommodation. It was advertised recently as a six bedroom let, a snip (!) at £3,360 pcm. The Bank of England inflation calculator tells me that in 1891, Edward Moore and his family would have been paying just under £26 a month. He had a large family comprising his wife Fanny Adelaide (36) and children Edwin James Moore (16), Fanny A Moore (14), William A Moore (13), Joseph C Moore (11), Rose Hannah Moore (10), Percy E Moore (8), Leonard J Moore (7) and Ernest F Moore (4).

SO FAR – On January 13th 1926, Milly Crabtree, 25 year-old wife of Cecl Crabtree, is found battered to death at their home, Manor Farm in Ladbroke. 19 year-old George Sharpes is arrested for her murder. As is the way with these, things, the wheels of justice turn very slowly, and it was February before Sharpes came to face magistrates in Southam. The courtroom, normally used as a cinema (pictured above), was packed, and the onlookers were spellbound as a confession from George Sharpes was read to the court.

SO FAR – On January 13th 1926, Milly Crabtree, 25 year-old wife of Cecl Crabtree, is found battered to death at their home, Manor Farm in Ladbroke. 19 year-old George Sharpes is arrested for her murder. As is the way with these, things, the wheels of justice turn very slowly, and it was February before Sharpes came to face magistrates in Southam. The courtroom, normally used as a cinema (pictured above), was packed, and the onlookers were spellbound as a confession from George Sharpes was read to the court.

The magistrates wasted little time in stating that George Sharpes had a serious case to answer, and the case was moved on to be examined at the March Assizes in Warwick. The case was presided over by Mr Justice Shearman. The only possible line for the defence to take was that Sharpes was insane at the time at the time he committed the murder, and Sharpes’s mother was produced to state that her son had suffered an unfortunate childhood. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, however. Rejecting the claims that George Sharpes was insane, the judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death. The execution was fixed for April and, as was almost always the case, a petition was set up to ask for clemency. The case was taken to appeal, in front of Lord Chief Justice Avory, who was perhaps not the most welcome choice for Sharpes’s defence team. Avory, a notorious “hanging judge”, had been memorably described:

The magistrates wasted little time in stating that George Sharpes had a serious case to answer, and the case was moved on to be examined at the March Assizes in Warwick. The case was presided over by Mr Justice Shearman. The only possible line for the defence to take was that Sharpes was insane at the time at the time he committed the murder, and Sharpes’s mother was produced to state that her son had suffered an unfortunate childhood. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, however. Rejecting the claims that George Sharpes was insane, the judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death. The execution was fixed for April and, as was almost always the case, a petition was set up to ask for clemency. The case was taken to appeal, in front of Lord Chief Justice Avory, who was perhaps not the most welcome choice for Sharpes’s defence team. Avory, a notorious “hanging judge”, had been memorably described:

Manor Farm in Ladbroke dates back, according to the data on British Listed Buildings, to the mid 18th century. For architectural historians, it adds:

Manor Farm in Ladbroke dates back, according to the data on British Listed Buildings, to the mid 18th century. For architectural historians, it adds:

England, 1923. Like thousands upon thousands of other young women, Esme Nicholls is a widow. Husband Alec lies in a functional grave in a military cemetery in Flanders. His face remains in a few photographs, and in her memories. Left penniless, she ekes out a living by writing a nature-notes feature for a northern provincial newspaper, and serving as a personal assistant to an older widow, Mrs Pickering. Mrs P has the advantage of being able to visit her husband’s grave whenever she wants, as he was not a victim of the war.

England, 1923. Like thousands upon thousands of other young women, Esme Nicholls is a widow. Husband Alec lies in a functional grave in a military cemetery in Flanders. His face remains in a few photographs, and in her memories. Left penniless, she ekes out a living by writing a nature-notes feature for a northern provincial newspaper, and serving as a personal assistant to an older widow, Mrs Pickering. Mrs P has the advantage of being able to visit her husband’s grave whenever she wants, as he was not a victim of the war. Caroline Scott (right) treats us to a high summer in Cornwall, where every flower, rustle of leaves in the breeze and flit of insect is described with almost intoxicating detail. Readers who remember her previous novel When I Come Home Again will be unsurprised by this detail. In the novel, she references that greatest of all poet of England’s nature, John Clare, but I also sense something of Matthew Arnold’s poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis, so memorably set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Caroline Scott (right) treats us to a high summer in Cornwall, where every flower, rustle of leaves in the breeze and flit of insect is described with almost intoxicating detail. Readers who remember her previous novel When I Come Home Again will be unsurprised by this detail. In the novel, she references that greatest of all poet of England’s nature, John Clare, but I also sense something of Matthew Arnold’s poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis, so memorably set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

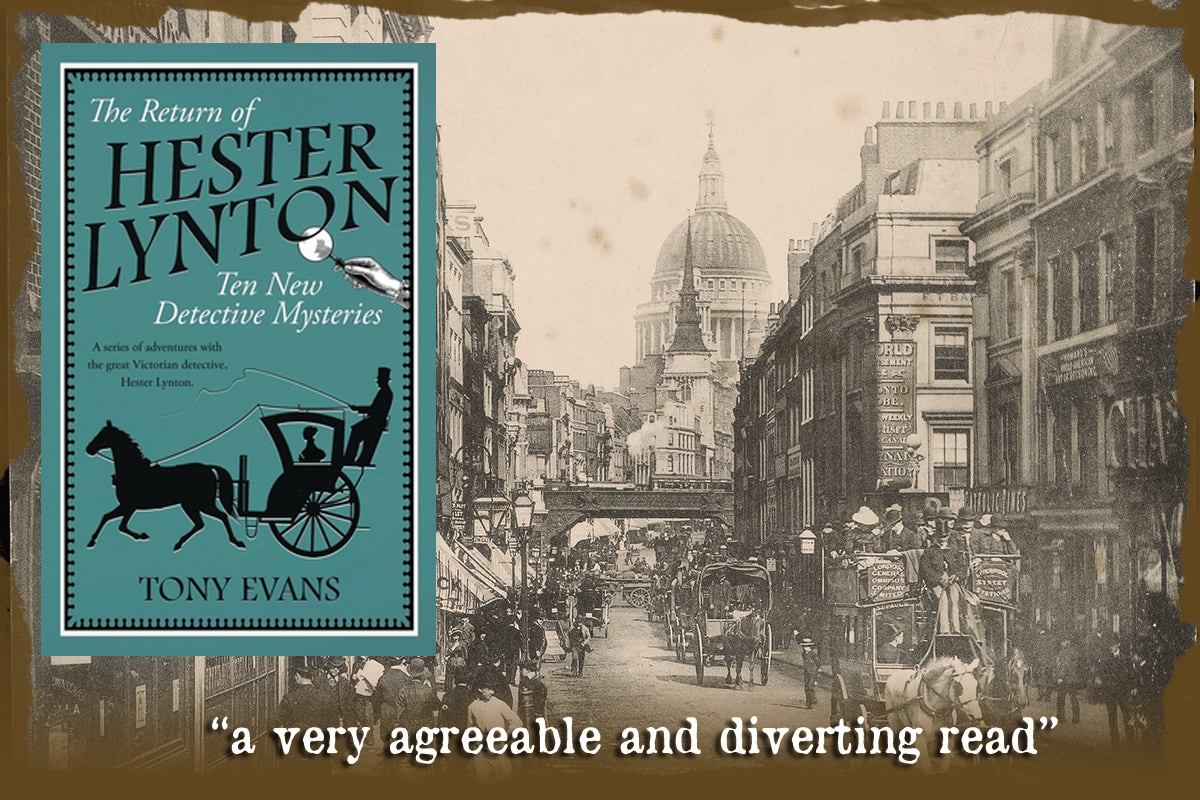

A rich widower, a self made industrialist, dies and leaves his fortune to be divided between his two nephews. One is a down-at-heel schoolmaster, the other a disreputable roué. The lucky man has to solve a cypher set by their late uncle. The good guy brings the cypher to Hester and Ivy. They solve the conundrum with by way of a knowledge of 18th century first editions, a journey to explore an ancient English church, and by breaking in to a family mausoleum.

A rich widower, a self made industrialist, dies and leaves his fortune to be divided between his two nephews. One is a down-at-heel schoolmaster, the other a disreputable roué. The lucky man has to solve a cypher set by their late uncle. The good guy brings the cypher to Hester and Ivy. They solve the conundrum with by way of a knowledge of 18th century first editions, a journey to explore an ancient English church, and by breaking in to a family mausoleum. Here, Tony Evans (right) indulges in the first of two shameless – but entertaining – instances of name-dropping. Our two sleuths, weary after a succession of difficult investigations, are enjoying some well-earned R & R in the resort of Whitby. So who do they meet? Think Irish writer and man of the theatre, blood, fangs …..? Gotcha! They are engaged by a fellow holidaymaker, a certain Mr B. Stoker to investigate the disappearance of a housemaid. She has been induced to leave her present employment to go and work for a rather dodgy doctor. Much skullduggery ensues, the housemaid is saved, and Mr Stoker says, “Hmm – this gives me an idea for a story.”

Here, Tony Evans (right) indulges in the first of two shameless – but entertaining – instances of name-dropping. Our two sleuths, weary after a succession of difficult investigations, are enjoying some well-earned R & R in the resort of Whitby. So who do they meet? Think Irish writer and man of the theatre, blood, fangs …..? Gotcha! They are engaged by a fellow holidaymaker, a certain Mr B. Stoker to investigate the disappearance of a housemaid. She has been induced to leave her present employment to go and work for a rather dodgy doctor. Much skullduggery ensues, the housemaid is saved, and Mr Stoker says, “Hmm – this gives me an idea for a story.”