For a good part of its long and curious history, it seems that The Peculiar Crimes Unit of London’s Metropolitan Police has been under threat. Civil servants and box-tickers without number have tried to close it down; it has endured bombs (courtesy of both the Luftwaffe and those closer to home); it has suffered plague and the eternal pestilence of whatever vile tobacco Arthur Bryant happens to stuffing into his pipe at any particular moment. The PCU has become:

“..like a flatulent elderly relative in a roomful of

millennials,a source of profound embarrassment..”

But now, yet another crisis seems to be the fatal straw that will break the back of the noble beast. Bryant’s partner John May (the sensible one) is on sick leave recovering from a near-fatal gunshot wound. Mr B has gone AWOL (trying to have his memoirs published), and the office has been invaded by a tight lipped (and probably ashen-faced) emissary from the Home Office who has instructions to observe what he sees and then report back to Whitehall.

The PCU creaks into arthritic action when Arthur Bryant puts his literary ambitions on hold, and links three apparently random deaths. A Romanian bookseller’s shop is torched, and he dies in police custody; a popular and (unusually) principled politician is grievously wounded, apparently by a pallet of citrus fruit falling from a lorry; a well-connected campaigning celebrity is stabbed to death on the steps of a notable London church. For Bryant, the game is afoot, and he draws on his unrivaled knowledge of London’s arcane history to convince his colleagues that the killer’s business is far from finished. His colleagues? Regular B&M fans will be relieved to know that, in the words of the 1917 American song (melody by Sir Arthur Sullivan) “Hail, Hail – The Gang’s All Here!”

An intern in the PCU? Yes, indeed, and in the words of Raymond Land;

“You may have noticed there’s an unfamiliar name attached to the recipients at the top of the page. Sidney Hargreaves is a girl. She’s happy to be called either Sid or Sidney because her name is, I quote, ‘non gender specific in an identity-based profession.’ It’s not for me to pass comment on gender, I got lost somewhere between Danny la Rue and RuPaul.”

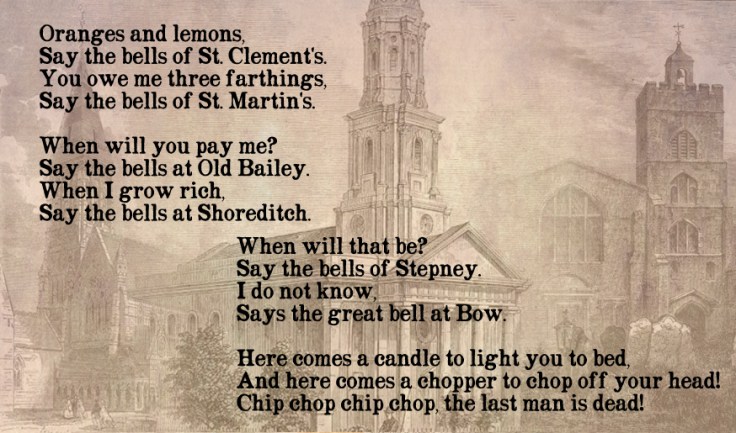

There are more deaths and Arthur Bryant is convinced that the killings are linked to the London churches immortalised in the old nursery rhyme, with its cryptic references:

But what links the victims to the killer? Beneath the joyous anarchy Arthur Bryant creates in the incomprehending digital world of modern policing, something very, very dark is going on. Fowler gives us hints, such as in this carefully selected verse between two sections of the book:

“The past is round us, those old spires

That glimmer o’er our head;

Not from the present are their fires,

Their light is from the dead.”

Also, underpinning the gags and joyfully sentimental cultural references there are moments of almost unbearable poignancy such as the moment when the two old men meet, as they always have done, on Waterloo Bridge, and think about loves won and lost and how things might have been.

There is no-one quite like Christopher Fowler among modern authors. He distills the deceptively probing gaze of John Betjeman, the sharp humour of George and Weedon Grossmith, the narrative drive of Arthur Conan Doyle and a knowledge of London’s darker corners and layers of history quite the equal of Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd, The result? A spirit that is as delicious as it is intoxicating. Oranges and Lemons is published by Doubleday and is out now.

More about the unique world of Arthur Bryant and John May can be found here, while anyone who would like to learn more about the origin of the rather sinister verse quoted earlier should click on the picture of its author, below, Letitia Elizabeth Landon.

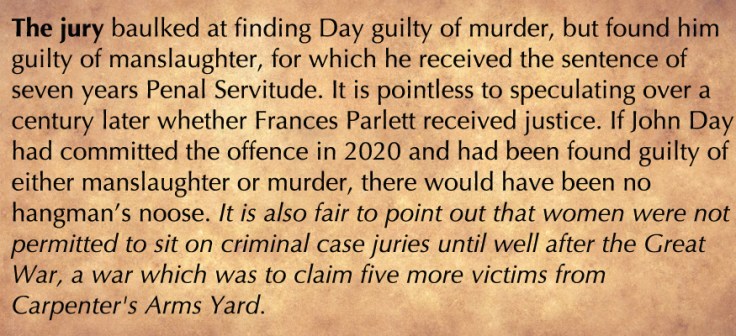

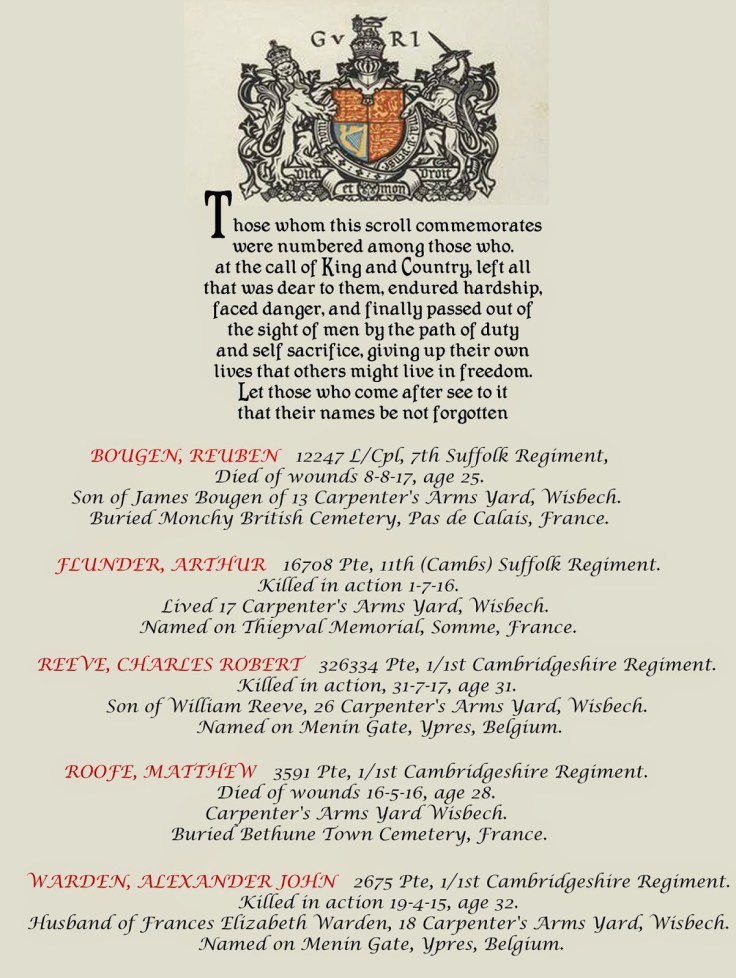

The photo on the right is of an existing Wisbech alley which, due to its central position has survived more or less intact, and gives us an idea of what the Yard might have looked like. Carpenter’s Arms Yard was earmarked for slum clearance in the late 1920s along with its near neighbour Ashworth’s Yard, and both were gone before the outbreak of World War II. What is now St Peter’s Road was probably more prosperous than either of the Yards, and its terraced houses were spared the redevelopments of the 1930s. It is tempting to look back and wish that more of old Wisbech had been preserved, but we would do well to remember that conditions in these old houses would be awful, even by standards of the time. Damp, insanitary and built on the cheap, these grim places contributed to the general poor health and high death rate of the time. The cemetery at the bottom of the slight slope of Carpenter’s Arms Yard was actually instituted as an overflow burial ground when a cholera epidemic struck the town earlier in the 19th century.

The photo on the right is of an existing Wisbech alley which, due to its central position has survived more or less intact, and gives us an idea of what the Yard might have looked like. Carpenter’s Arms Yard was earmarked for slum clearance in the late 1920s along with its near neighbour Ashworth’s Yard, and both were gone before the outbreak of World War II. What is now St Peter’s Road was probably more prosperous than either of the Yards, and its terraced houses were spared the redevelopments of the 1930s. It is tempting to look back and wish that more of old Wisbech had been preserved, but we would do well to remember that conditions in these old houses would be awful, even by standards of the time. Damp, insanitary and built on the cheap, these grim places contributed to the general poor health and high death rate of the time. The cemetery at the bottom of the slight slope of Carpenter’s Arms Yard was actually instituted as an overflow burial ground when a cholera epidemic struck the town earlier in the 19th century.

Fictional police officers come in an almost infinite number of guises. They can be lowly of rank, like Tony Parsons’ Detective Constable Max Wolfe, or very senior, such as Detective Superintendent William Lorimer, as imagined by Alex Gray. Male, female, tech-savvy, Luddite, happy family folk or embittered loners – there are plenty to choose from. So where does Peter Lovesey’s Peter Diamond fit into the matrix? As a Detective Superintendent, he pretty much only answers to the Assistant Chief Constable, but for newcomers to the well established series, what sort of a figure does he cut? Lovesey lets us know fairly early in The Finisher, the nineteenth in a series that began in 1991 with The Last Detective. Diamond is on plain clothes duty keeping a wary eye on a half marathon race in the historic city of Bath:

Fictional police officers come in an almost infinite number of guises. They can be lowly of rank, like Tony Parsons’ Detective Constable Max Wolfe, or very senior, such as Detective Superintendent William Lorimer, as imagined by Alex Gray. Male, female, tech-savvy, Luddite, happy family folk or embittered loners – there are plenty to choose from. So where does Peter Lovesey’s Peter Diamond fit into the matrix? As a Detective Superintendent, he pretty much only answers to the Assistant Chief Constable, but for newcomers to the well established series, what sort of a figure does he cut? Lovesey lets us know fairly early in The Finisher, the nineteenth in a series that began in 1991 with The Last Detective. Diamond is on plain clothes duty keeping a wary eye on a half marathon race in the historic city of Bath: There’s a dazzling array of characters to act out the drama. We have an earnest school teacher who forces herself to run the race in order to make good a lost donation to a charity; there is a statuesque Russian, wife of a cynical businessman, determined to lose weight and gain her husband’s respect; instant villainy is provided by a paroled serial seducer and sex-pest who has taken on a new role as personal trainer to the rich; at the bottom of the pond, so to speak, are a pair of feckless Albanian chancers who have escaped from an illegal work gang, and are trying to avoid the retribution of their controllers.

There’s a dazzling array of characters to act out the drama. We have an earnest school teacher who forces herself to run the race in order to make good a lost donation to a charity; there is a statuesque Russian, wife of a cynical businessman, determined to lose weight and gain her husband’s respect; instant villainy is provided by a paroled serial seducer and sex-pest who has taken on a new role as personal trainer to the rich; at the bottom of the pond, so to speak, are a pair of feckless Albanian chancers who have escaped from an illegal work gang, and are trying to avoid the retribution of their controllers.

Strangely though, Find Them Dead sees Roy Grace rather in the background. He binds the narrative together by his presence, of course he does, but he mostly takes a back seat in this tale of drug dealers, bent lawyers and jury-nobbling. He has returned to Sussex after a spell working with the Metropolitan Police in London. The sheer depth and depravity of London’s crime has been an eye-opener, but the south coast is not without its villains.

Strangely though, Find Them Dead sees Roy Grace rather in the background. He binds the narrative together by his presence, of course he does, but he mostly takes a back seat in this tale of drug dealers, bent lawyers and jury-nobbling. He has returned to Sussex after a spell working with the Metropolitan Police in London. The sheer depth and depravity of London’s crime has been an eye-opener, but the south coast is not without its villains.

This is a very different Rob Parker (left) from the previous novels of his that have come my way.

This is a very different Rob Parker (left) from the previous novels of his that have come my way.