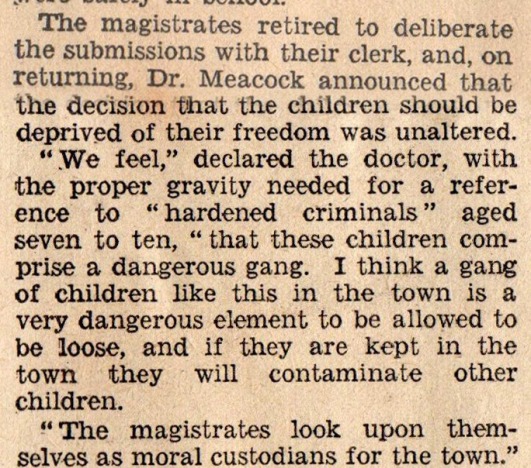

The story so far. “SCHOOLBOY GANGSTERS ROUNDED UP!” screamed the local papers. According to Dr Meacock, who chaired the Special Children’s Court, the boys,

“constituted a centre of vice in the town,and they must be dealt with drastically.”

Those of you who follow my posts will remember that Dr Meacock was at the very heart of the controversy surrounding the life and death of Dr Horace Dimock, twenty years earlier, an unfortunate situation which resulted in the infamous riots. So, who were these five desperadoes, and what were the Industrial Schools to which they were to be packed off, until they reached the age of 16?

Firstly the names of the boys. I received this information from the County Record Office. I imagine they are all now deceased, but at the time their names would not have been available in the press, for legal reasons. They were:

Horace Stephen Freear, age 7

Frederick Hunt, age 8

Stanley Johnson, age 9

Harry Rivett, age 10

Harry Worth, age 10

Their sentence? To spend the years in an Industrial School, until they reached the age of 16. For Worth and Rivett – a 6 year sentence; for Johnson, 7 years; Hunt would serve 8 years, and Freear a staggering 9 years.

The words ‘Industrial School’ have a vaguely worthy ring to them. There’s a suggestion that they were places where youngsters could learn a trade, benefit from a healthy lifestyle, and be taught the errors of whatever ways had led them to become inmates. Older readers will remember the words ‘Reform School’ and ‘Borstal’. These days we skip around the truth with phrases like ‘Young Offenders Institution’, but the fact remains that Industrial schools were usually grim places which probably served as training grounds for future lawbreakers. The industrial schools were invariably grim and forbidding places but it doesn’t seem that one existed in Cambridgeshire, with the nearest one being in Suffolk.

To their eternal credit, there were those in Wisbech who thought the sentence handed down to these boys was excessive. To use modern parlance, they may well have been “thieving little scrotes”, but even so, this was a draconian sentence, even by the standards of 1933. Spearheaded by a Baptist minister, the Reverend R N Armitage (pictured below), a fund was started to appeal the boys’ sentence.

Then, the big guns turned on Dr Meacock and the other people alongside him who actually were magistrates. It seems that Meacock had no business being in that court, and with the benefit of hindsight, it seems that the infamous Old Pals’ Act was alive and well in Wisbech. The popular national periodical, John Bull, said its piece. After repeating the findings of the magistrates, the journal then let rip.

The case of the Five Little Martyrs is not simply one of a wrong being righted. It has a curiously modern feel to it, with its far-reaching echoes of relatively minor misdeeds being met by extravagant punishment. The boys were clearly beyond parental control. and their group had a velocity and dynamic all of its own. Yes, the hauls from their thieving – ten bob, some pig serum, cycle lamps and a packet of Aspros (remember them?) seem comical.

The case of the Five Little Martyrs is not simply one of a wrong being righted. It has a curiously modern feel to it, with its far-reaching echoes of relatively minor misdeeds being met by extravagant punishment. The boys were clearly beyond parental control. and their group had a velocity and dynamic all of its own. Yes, the hauls from their thieving – ten bob, some pig serum, cycle lamps and a packet of Aspros (remember them?) seem comical.

However, you only need to follow local Facebook groups nowadays to read accounts of similar misdemeanours, on the same streets as the Infamous Five frequented, to read violently worded responses from people who feel that ‘feral youths‘ (a term not yet invented in 1933) are making their lives a misery. The people who ran Wisbech in 1933 – in particular Dr Meacock – don’t emerge from this saga with any honour. Sadly, some things never change.

I write as someone who lives in Wisbech, and I can tell you that in 2020, eighty seven years on from the events I describe in this feature, modern day versions of Dr Meacock are alive and well, still with theirhands on the tiller.

So, what became of The Five Little Martyrs? The records tell us that a Horace Stephen Freear died in 1978, and that a Frederick Hunt died in 1971. Of the others, no-one knows what they did with their lives after they, briefly, became national figures.

The floral tributes included the following:

The floral tributes included the following: A century or more later, what do we make of the affair? What happened to the participants who survived? Reading contemporary accounts, it is difficult to believe that Horace Dimock was a totally innocent party. It would have been perfectly possible for him to have won the hearts of his patients, many of them from the poorer side of society, at the same time as conducting a hate campaign against those fellow professionals against whom he bore a grudge. The less lurid of the postcards allegedly sent by Dr Dimock were reproduced in the press, along with detailed evidence by so-called handwriting experts.

A century or more later, what do we make of the affair? What happened to the participants who survived? Reading contemporary accounts, it is difficult to believe that Horace Dimock was a totally innocent party. It would have been perfectly possible for him to have won the hearts of his patients, many of them from the poorer side of society, at the same time as conducting a hate campaign against those fellow professionals against whom he bore a grudge. The less lurid of the postcards allegedly sent by Dr Dimock were reproduced in the press, along with detailed evidence by so-called handwriting experts.

In Wisbech this was a problem

In Wisbech this was a problem

So, the people’s favourite,

So, the people’s favourite,