Like most of the other novels in this excellent Imperial War Museum series of republications (see the end of this review) Warriors For The Working Day is semi-autobiographical. Peter Elstob (left) was a tank commander as part of the 11th Armoured Division. His own service closely mirrors that of Michael Brook, the central character in the novel.

Elstob vividly captures the intense claustrophobia of being part of a tank crew, and the awareness that they were sitting inside a potential bomb:

“Uncertainty and a preoccupation with defence ran through the troop like a shiver and reminded them that they were imprisoned in large, slow moving steel boxes full of explosive and gallons of readily inflammable petrol.”

Brook and his comrades are fighting an enemy who is frequently invisible and most probably using a better machine than theirs. An understanding the technology of tank warfare in 1944 is crucial to getting closer to the mindset of the men in the novel.

For the greater part of the book, Brook and his crew are in a Sherman tank. These were American, produced in vast numbers, and relatively easy to repair and maintain. The main danger came from the 8.8cm Flak artillery piece, originally designed as an anti-aircraft weapon, but utterly lethal when used as an anti-tank gun, particularly when firing armour-piercing rounds, which would cut into a Sherman like a knife through butter. The enemy tanks – Panzers – would have included the formidable Tiger, with its hugely superior firepower and armour plate. Luckily for the Allies, the German tanks were fewer in number and probably over-engineered, making repairs in the field very difficult.

The relentless movement of the narrative follows the tanks as they break out of Normandy and head north-east towards the old battle grounds of the Great War, through the debacle of Operation Market Garden and then, in the depths of winter, to face what was Hitler’s last throw of the dice in what became known as The Battle of The Bulge. The final episode of the saga sees Brook and his weary colleagues crossing The Rhine and fighting the Germans on their own soil.

Along the way, Brook gains new friends but loses old ones, while learning something about the nature of battle fatigue:

“Most of them were unaware that anything much was wrong with them, for they were uncomplicated men not given to introspection. They knew they were frightened, but they knew that everyone else was frightened too, and had come to realise that wars are fought by a few frightened men facing each other – the sharp end of the sword …’

Violent death is ubiquitous and frequent, but has to be dealt with:

“‘I’ve just been talking to the Q – Tim Cadey’s dead.’

He told them because he had to tell them. They said the conventional things for a minute or two and then changed the subject. It was not the time to recall the small details of Tim Cadey, or ‘Tich’ Wilson, his driver, or Owen and his singing. It was best to try and forget them all immediately.”

In their progress into Germany, Brook and his crew pass a mysterious wired enclosure surrounded by tall watchtowers:

‘‘They certainly don’t intend to let their prisoners escape,’ said Bentley. ‘What’s the name of this place, Brookie?’

Brook reached for the map on top of the wireless and found their route. ‘That village the Tiger was in front of was called Walle … and the town up ahead is Bergen, so this must be …Belsen. Yes, that’s right, it’s called Belsen.’

‘Never ‘eard of it, ‘ said Geordie, jokingly. ‘But I wouldn’t want to live ‘ere.'”

Warriors For The Working Day is a deeply compassionate and moving account of men at war, simply told, but without bitterness or rancour; it is the work of a man who was there, and knew the tears, the laughter, the bravery – and the human frailty.

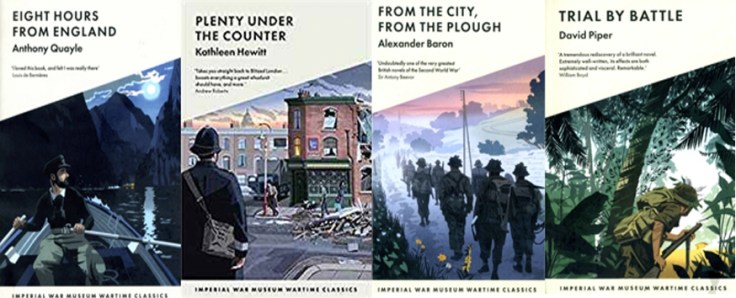

To read my reviews of other books in this series, click on the image below.

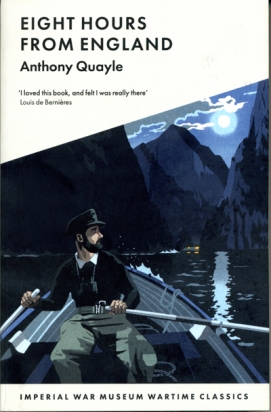

To many of us who grew up in the 1950s Anthony Quayle was to become one of a celebrated group of theatrical knights, along with Olivier, Gielgud, Richardson and Redgrave. Until recently I had no idea that he was also wrote two novels based on his experiences in WW2. The first of these, Eight Hours From England was first published in 1945 and is the fourth and final reprint in the impressive series from the Imperial War Museum.

To many of us who grew up in the 1950s Anthony Quayle was to become one of a celebrated group of theatrical knights, along with Olivier, Gielgud, Richardson and Redgrave. Until recently I had no idea that he was also wrote two novels based on his experiences in WW2. The first of these, Eight Hours From England was first published in 1945 and is the fourth and final reprint in the impressive series from the Imperial War Museum.

Of the three classic reprints which feature overseas action Eight Hours From England is the bleakest by far. The books by Alexander Baron and David Piper bear solemn witness to the deaths of brave men, sometimes heroic but often simply tragic: the irony is that Overton and his men do not, as far as I can recall, actually fire a shot in anger. No Germans are killed as a result of their efforts; the Allied cause is not advanced by the tiniest fraction; their heartbreaking struggle is not against the swastika and all it stands for, but against a brutally inhospitable terrain, bitter weather and, above all, the distrust, treachery and embedded criminality of many of the Albanians they encounter.

Of the three classic reprints which feature overseas action Eight Hours From England is the bleakest by far. The books by Alexander Baron and David Piper bear solemn witness to the deaths of brave men, sometimes heroic but often simply tragic: the irony is that Overton and his men do not, as far as I can recall, actually fire a shot in anger. No Germans are killed as a result of their efforts; the Allied cause is not advanced by the tiniest fraction; their heartbreaking struggle is not against the swastika and all it stands for, but against a brutally inhospitable terrain, bitter weather and, above all, the distrust, treachery and embedded criminality of many of the Albanians they encounter.

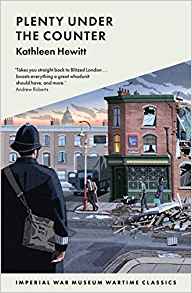

his 1943 novel by Kathleen Hewitt is the third in the excellent series of Imperial War Museum reprints of wartime classics, but couldn’t be more different from the first two,

his 1943 novel by Kathleen Hewitt is the third in the excellent series of Imperial War Museum reprints of wartime classics, but couldn’t be more different from the first two,  A jolly murder? Well, of course. Fictional murders can be range from brutal to comic depending on the genre, and although the corpse found in the back garden of Mrs Meake’s lodging house – 15 Terrapin Road – is just as dead as any described by Val McDermid or Michael Connelly, the mood is set by the chief amateur investigator, a breezy and frightfully English RAF pilot called David Heron on recuperation leave from his squadron, and his elegantly witty lady friend Tess. He is from solid county stock:

A jolly murder? Well, of course. Fictional murders can be range from brutal to comic depending on the genre, and although the corpse found in the back garden of Mrs Meake’s lodging house – 15 Terrapin Road – is just as dead as any described by Val McDermid or Michael Connelly, the mood is set by the chief amateur investigator, a breezy and frightfully English RAF pilot called David Heron on recuperation leave from his squadron, and his elegantly witty lady friend Tess. He is from solid county stock: eaders will not need a degree in 20th century social history to recognise that the book’s title refers to the methods used by shopkeepers to circumvent the official rationing of food and fancy goods. More sinister is the presence – both in real life and in the book – of criminals who exploit the shortages to make serious money playing the black market and for whom deadly violence is just a way of life.

eaders will not need a degree in 20th century social history to recognise that the book’s title refers to the methods used by shopkeepers to circumvent the official rationing of food and fancy goods. More sinister is the presence – both in real life and in the book – of criminals who exploit the shortages to make serious money playing the black market and for whom deadly violence is just a way of life.

The story rattles along in fine style as the hours tick by before David has to return to the war. He has two pressing needs. One is to buy the special licence which will enable him to marry Tess, and the other is to find the Terrapin Road murderer. Hewitt (right) is too good a writer to leave her story lightly bobbing about on the bubbles of wartime champagne (probably a toxic mix of white wine and ginger ale) and she darkens the mood in the last few pages, leaving us to ponder the nature of tragedy and self-sacrifice.

The story rattles along in fine style as the hours tick by before David has to return to the war. He has two pressing needs. One is to buy the special licence which will enable him to marry Tess, and the other is to find the Terrapin Road murderer. Hewitt (right) is too good a writer to leave her story lightly bobbing about on the bubbles of wartime champagne (probably a toxic mix of white wine and ginger ale) and she darkens the mood in the last few pages, leaving us to ponder the nature of tragedy and self-sacrifice.

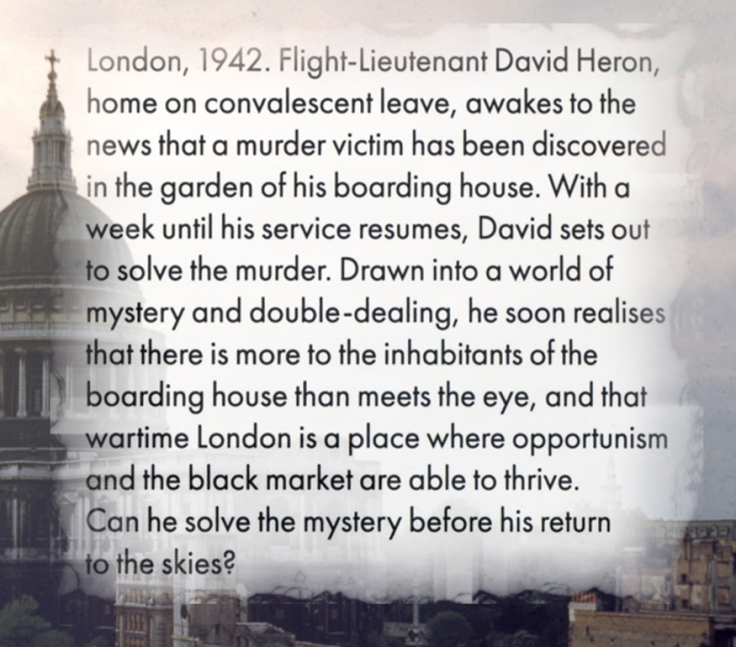

his is not a conventional crime novel. There are victims, for sure, and perpetrators of terrible acts which still, when described, take the breath away in their depravity and cold, organised manifestation of evil. English academic Martin Goodman (right)

his is not a conventional crime novel. There are victims, for sure, and perpetrators of terrible acts which still, when described, take the breath away in their depravity and cold, organised manifestation of evil. English academic Martin Goodman (right)  has written a starkly brilliant account of Nazi oppression in Central Europe in the late 1930s. He achieves his broad sweep by, paradoxically focusing on the fine detail. One family. One teenage boy, Otto Schalmek. One fateful knock on the door while Vienna and most of Austria are waving flags to welcome ‘liberation’ in the shape of the Anschluss.

has written a starkly brilliant account of Nazi oppression in Central Europe in the late 1930s. He achieves his broad sweep by, paradoxically focusing on the fine detail. One family. One teenage boy, Otto Schalmek. One fateful knock on the door while Vienna and most of Austria are waving flags to welcome ‘liberation’ in the shape of the Anschluss. The Schalmek family are Jewish. That is all that needs to be said. The family becomes just a few lines on a ledger – immaculately kept – which records the ‘resettlement’ of Jewish families. Otto is taken to Dachau and then to Birkenau. His ability as a cellist precedes him, and he is sent to play in the house of Birchendorf, the camp Commandant. His wife Katja is the artistic one, and her husband merely seeks to keep her entertained by using Schalmek as a kind of performing monkey who plays Bach suites on the cello in between sanding floors and mopping up shit in the latrines.

The Schalmek family are Jewish. That is all that needs to be said. The family becomes just a few lines on a ledger – immaculately kept – which records the ‘resettlement’ of Jewish families. Otto is taken to Dachau and then to Birkenau. His ability as a cellist precedes him, and he is sent to play in the house of Birchendorf, the camp Commandant. His wife Katja is the artistic one, and her husband merely seeks to keep her entertained by using Schalmek as a kind of performing monkey who plays Bach suites on the cello in between sanding floors and mopping up shit in the latrines. oodman’s book spans the years and the continents. Having been shown the shattering of the Schalmek family we go from the Nuremburg trials to late 1940s Canada and then, via Sydney in the 1960s, on to 1990s California, where Katja’s grand-daughter Rosa, an eminent writer and musicologist, seeks an audience with the elusive and very private genius Otto Schalmek. Rosa Cline is determined to write the definitive biography of Otto Schalmek, but their relationship takes an unexpected turn.

oodman’s book spans the years and the continents. Having been shown the shattering of the Schalmek family we go from the Nuremburg trials to late 1940s Canada and then, via Sydney in the 1960s, on to 1990s California, where Katja’s grand-daughter Rosa, an eminent writer and musicologist, seeks an audience with the elusive and very private genius Otto Schalmek. Rosa Cline is determined to write the definitive biography of Otto Schalmek, but their relationship takes an unexpected turn. is a distinctive and beautifully written novel, full of irony, heartbreak and a scholarly brilliance in the way it portrays the human devastation of Hitler’s assault on the Jews. Yes, there is the almost obligatory account of the depravity and sheer horror of the camps, but Goodman also brings a sense of great intimacy and a telling focus on the small personal tragedies and discomforts – an interrupted family meal, a tearful and hurried “goodbye”, and a new grandchild never to be cuddled by grandparents. Crime fiction? Probably not, in the scheme of things. Thrilling, often painful, and full of psychological insight? Certainly. J SS Bach is published by

is a distinctive and beautifully written novel, full of irony, heartbreak and a scholarly brilliance in the way it portrays the human devastation of Hitler’s assault on the Jews. Yes, there is the almost obligatory account of the depravity and sheer horror of the camps, but Goodman also brings a sense of great intimacy and a telling focus on the small personal tragedies and discomforts – an interrupted family meal, a tearful and hurried “goodbye”, and a new grandchild never to be cuddled by grandparents. Crime fiction? Probably not, in the scheme of things. Thrilling, often painful, and full of psychological insight? Certainly. J SS Bach is published by

In this febrile atmosphere are many men and women who have memories of “the last lot”. One such is the latest creation from Jim Kelly, (left) Detective Inspector Eden Brooke. He saw service in The Great War, but were someone to wonder if his war had been ‘a good war’, they would soon discover that he had suffered dreadful privations and abuse as a prisoner of the Turks, and that the most physical legacy of his experiences is that his eyesight has been permanently damaged. He wears a selection of spectacles with lenses tinted to block out different kinds of light which cause him excruciating pain. For him, therefore, the nightly blackout is more of a blessing than a hindrance.

In this febrile atmosphere are many men and women who have memories of “the last lot”. One such is the latest creation from Jim Kelly, (left) Detective Inspector Eden Brooke. He saw service in The Great War, but were someone to wonder if his war had been ‘a good war’, they would soon discover that he had suffered dreadful privations and abuse as a prisoner of the Turks, and that the most physical legacy of his experiences is that his eyesight has been permanently damaged. He wears a selection of spectacles with lenses tinted to block out different kinds of light which cause him excruciating pain. For him, therefore, the nightly blackout is more of a blessing than a hindrance.

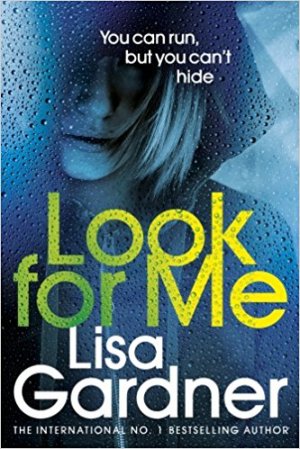

Look For Me is a return to active duty for Boston Detective D D Warren. In the twelfth book of an obviously popular series, Gardner brings back a character – Flora Dane – from an earlier book, Find Her, in which Dane was a resilient but haunted survivor of kidnap and abduction. Now, Dane’s thirst for vengeance on her tormentor is a mixed blessing for Warren who is faced with a murder scene of almost unimaginable violence. Four members of the same family lie slaughtered in the family home, a refuge transformed into a charnel house. But where is the fifth member of the family? Has the sixteen year-old girl escaped, or is her disappearance the prelude to an even greater evil? Look For Me is published by Century, part of the Penguin Random House group, and will be available in early February 2018. You can pre-order a copy

Look For Me is a return to active duty for Boston Detective D D Warren. In the twelfth book of an obviously popular series, Gardner brings back a character – Flora Dane – from an earlier book, Find Her, in which Dane was a resilient but haunted survivor of kidnap and abduction. Now, Dane’s thirst for vengeance on her tormentor is a mixed blessing for Warren who is faced with a murder scene of almost unimaginable violence. Four members of the same family lie slaughtered in the family home, a refuge transformed into a charnel house. But where is the fifth member of the family? Has the sixteen year-old girl escaped, or is her disappearance the prelude to an even greater evil? Look For Me is published by Century, part of the Penguin Random House group, and will be available in early February 2018. You can pre-order a copy  Polish history in the twentieth century shows us a region constantly in the thick of conflict between rival military forces. It was the scene of many of the battles on the Eastern Front during WWI, and Poland suffered hugely at the hands of the Nazis during WWII. The very worst concentration camps set up by Hitler were on what is now Polish territory. Then, post-war, came what was, to all intents and purposes, a Russian occupation. Peter Haden’s novel Jan actually deals with a real person, his uncle, Jan Janicki and his exploits both before and during the Nazi occupation of his homeland. The novel tells of a flight from desperate domestic poverty, the humiliation of working for the ruthless German invaders, but then a determination to fight back, which sees Jan laying his life on the line to support the Polish resistance movement. Jan is published by Matador, and is available from

Polish history in the twentieth century shows us a region constantly in the thick of conflict between rival military forces. It was the scene of many of the battles on the Eastern Front during WWI, and Poland suffered hugely at the hands of the Nazis during WWII. The very worst concentration camps set up by Hitler were on what is now Polish territory. Then, post-war, came what was, to all intents and purposes, a Russian occupation. Peter Haden’s novel Jan actually deals with a real person, his uncle, Jan Janicki and his exploits both before and during the Nazi occupation of his homeland. The novel tells of a flight from desperate domestic poverty, the humiliation of working for the ruthless German invaders, but then a determination to fight back, which sees Jan laying his life on the line to support the Polish resistance movement. Jan is published by Matador, and is available from  From Poland to Italy, where much of A Time For Role Call by Doug Thompson (left) is set. Former Professor of Modern Italian language, history and literature, Doug Thompson draws on his intimate knowledge of Italy to write a lively novel with a feisty protagonist and colourful cast of supporting characters. Sally Jardine-Fell is recruited by the wartime Special Operations Executive to travel to Italy. Her mission? To insinuate herself into the life of none other than Count Galeazo Ciano, Foreign Minister to Il Duce – Benito Mussolini – himself. Inevitably, things do not go according to plan, and, despite both the war and Mussolini himself becoming consigned to history, events conspire against Sally, and she finds herself in a cell, charged with murder. A Time For Role Call is published by Matador, and is available

From Poland to Italy, where much of A Time For Role Call by Doug Thompson (left) is set. Former Professor of Modern Italian language, history and literature, Doug Thompson draws on his intimate knowledge of Italy to write a lively novel with a feisty protagonist and colourful cast of supporting characters. Sally Jardine-Fell is recruited by the wartime Special Operations Executive to travel to Italy. Her mission? To insinuate herself into the life of none other than Count Galeazo Ciano, Foreign Minister to Il Duce – Benito Mussolini – himself. Inevitably, things do not go according to plan, and, despite both the war and Mussolini himself becoming consigned to history, events conspire against Sally, and she finds herself in a cell, charged with murder. A Time For Role Call is published by Matador, and is available

Jack Grimwood’s Moskva sets out to convince us that there is room for one more tale of conflicted lives in a modern Russia full of paradox and uncertainty. The book came out in hardback earlier this year, and is now available in paperback, from Penguin. Does Grimwood, who made his name writing science fiction and fantasy novels, hit the spot?

Jack Grimwood’s Moskva sets out to convince us that there is room for one more tale of conflicted lives in a modern Russia full of paradox and uncertainty. The book came out in hardback earlier this year, and is now available in paperback, from Penguin. Does Grimwood, who made his name writing science fiction and fantasy novels, hit the spot? The breadth of this novel in terms of time sometimes makes it hard to work out who has done what to whom. Patience – and a spot of back-tracking – will pay dividends, however, and the narrative provides a salutary reminder of the sheer magnitude of the numbers of Russian dead in WWII, and the resultant near-psychosis about The West. To top-and-tail this review and answer the earlier question as to whether Jack Grimwood (right) “hits the spot”, I can give a resounding “Yes!”. Yes, the plot is complex, and yes, you will need your wits about you, but yes, it’s a riveting read; yes, Tom Fox is a flawed but engaging central character, and yes, Grimwood has sharp-elbowed his way into the line-up of novelists who have written convincing crime novels set in the enigma that is Russia.

The breadth of this novel in terms of time sometimes makes it hard to work out who has done what to whom. Patience – and a spot of back-tracking – will pay dividends, however, and the narrative provides a salutary reminder of the sheer magnitude of the numbers of Russian dead in WWII, and the resultant near-psychosis about The West. To top-and-tail this review and answer the earlier question as to whether Jack Grimwood (right) “hits the spot”, I can give a resounding “Yes!”. Yes, the plot is complex, and yes, you will need your wits about you, but yes, it’s a riveting read; yes, Tom Fox is a flawed but engaging central character, and yes, Grimwood has sharp-elbowed his way into the line-up of novelists who have written convincing crime novels set in the enigma that is Russia.