In the thirteenth episode of what is a genuinely impressive series, David Mark’s Hull copper Aector McAvoy returns, along with the established cast – his wife Roisin and their two children, and his boss, Detective Superintendent Trish Pharoah. McAvoy is, as the name suggests, a Scottish exile, and he is built like the proverbial brick you-know-what. Despite his forbidding appearance, McAvoy is a peaceable and studious man, shy with other people, but perceptive and with an attention to detail that matches his formidable appearance.

The book begins with a flashback to an attempt by young men to carry out what seems to be a robbery in an isolated rural property. It ends in horrific violence, matched only by the destructive storm that rages over the heads of the ill-advised and ill-prepared group. Cut to the present day, and another storm has lashed Humberside, bringing down power lines, flooding homes, and uprooting trees. One such tree, an ancient ash, reveals something truly awful – a human body, mostly decayed, entwined within its roots in a macabre embrace.

The book begins with a flashback to an attempt by young men to carry out what seems to be a robbery in an isolated rural property. It ends in horrific violence, matched only by the destructive storm that rages over the heads of the ill-advised and ill-prepared group. Cut to the present day, and another storm has lashed Humberside, bringing down power lines, flooding homes, and uprooting trees. One such tree, an ancient ash, reveals something truly awful – a human body, mostly decayed, entwined within its roots in a macabre embrace.

McAvoy is called to the scene, and it doesn’t take too much evidence – in this case a pair of fashionable trainers – for McAvoy to deduce that this body has been put into the ground in living memory. What is astonishing, however, is that two Roman coins have been nailed into the victim’s eyes. The gentle policeman can only hope and pray that this act was not done while the victim was still alive. To make matters more disturbing, the fragile bones of two babies are also found.

The body is soon identified as that of a university student who went missing in the 1990s, but what on earth was he doing in this remote spot, and who had cause to kill and maim him in such a fashion? The owners of the adjacent property are interviewed, but add nothing to the investigation. Pharoah and McAvoy discover that the case may be linked to the trade in ancient artifacts discovered by illegal metal detectorists – nighthawks – and there is disturbing evidence that a notorious Manchester gangster – convicted of horrific torture just a few years earlier – may be involved on the fringes of the case.

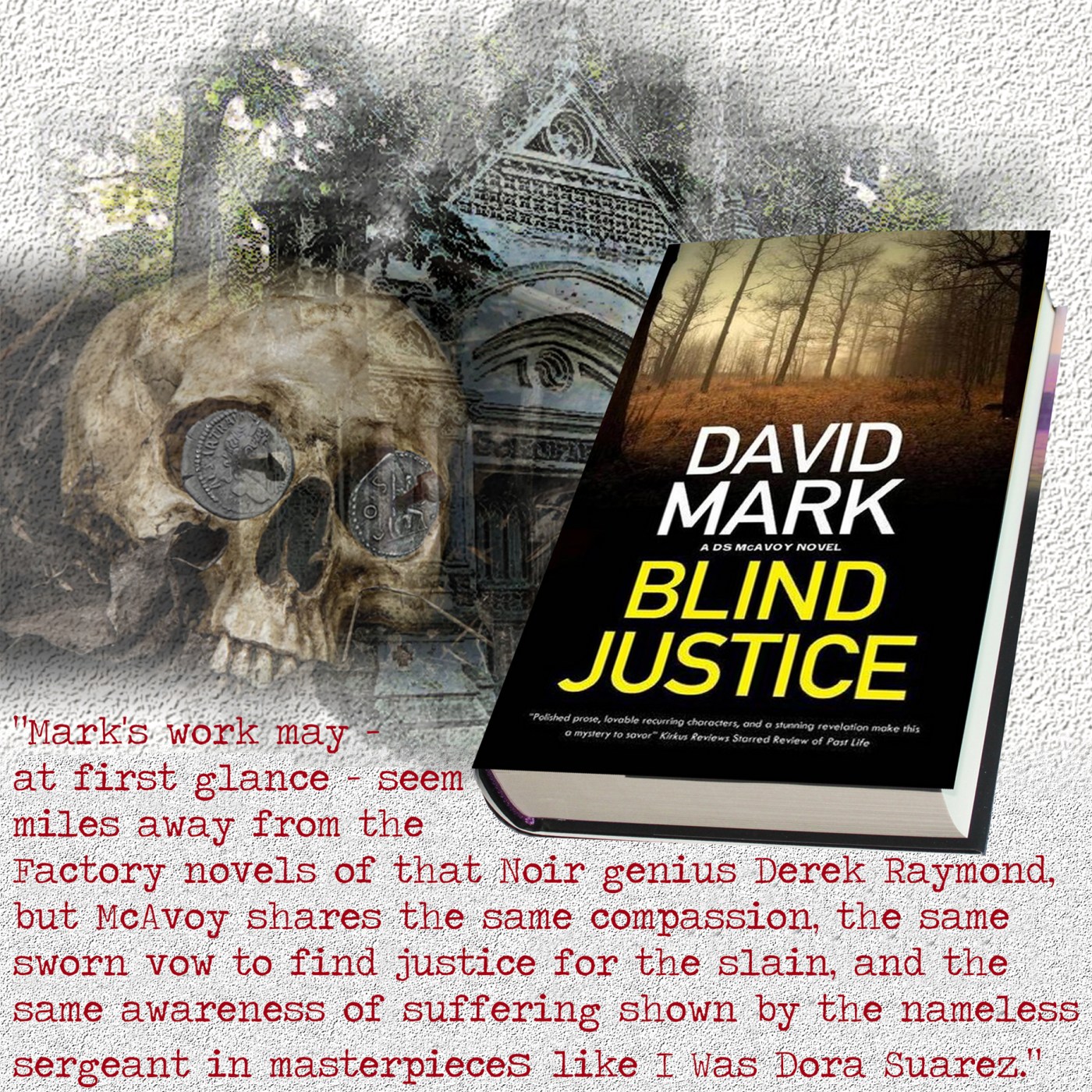

David Mark (right) writes with a sometimes frightening intensity as dark events swirl around Aector McAvoy. The big man, gentle and hesitant though he may seem, is, however, like a rock. He is one of the most original creations in a very crowded field of fictional British coppers, and his capacity to bear pain for others – particularly in this episode his son Fin and Trish Pharoah – is movingly described. Mark’s work may – at first glance – seem miles away from the Factory novels of that Noir genius Derek Raymond, but McAvoy shares the same compassion, the same sworn vow to find justice for the slain, and the same awareness of suffering shown by the nameless sergeant in masterpieces like I Was Dora Suarez.

David Mark (right) writes with a sometimes frightening intensity as dark events swirl around Aector McAvoy. The big man, gentle and hesitant though he may seem, is, however, like a rock. He is one of the most original creations in a very crowded field of fictional British coppers, and his capacity to bear pain for others – particularly in this episode his son Fin and Trish Pharoah – is movingly described. Mark’s work may – at first glance – seem miles away from the Factory novels of that Noir genius Derek Raymond, but McAvoy shares the same compassion, the same sworn vow to find justice for the slain, and the same awareness of suffering shown by the nameless sergeant in masterpieces like I Was Dora Suarez.

The terrifying climax to Blind Justice is also straight out of the Derek Raymond playbook and is not for the squeamish, but vivid and visceral. Where David Mark does differ from his illustrious predecessor is that he allows McAvoy the redemption and respite denied to Raymond’s sergeant with his dead child and mad wife, and it comes in the shape of his intriguing part-gypsy wife and their children.

If I read a better book all year, be sure that I will let you know. Blind Justice is published by Severn House and will be out on 31st March.

That reminiscence may seem unrelated to a book review, but it is relevant. When reviewing the latest book in a long and successful series it is tempting to think that all prospective readers will be fully up to speed with the quirks and history of the main characters. But that’s not so. Thankfully, people come to books at different times and for different reasons, so a paragraph about Edinburgh copper DI Tony McLean won’t be wasted. If you already know, then just skip ahead.

That reminiscence may seem unrelated to a book review, but it is relevant. When reviewing the latest book in a long and successful series it is tempting to think that all prospective readers will be fully up to speed with the quirks and history of the main characters. But that’s not so. Thankfully, people come to books at different times and for different reasons, so a paragraph about Edinburgh copper DI Tony McLean won’t be wasted. If you already know, then just skip ahead.

We have the advantage over the police in that we are introduced early on to the man who dropped the suitcase from the bridge into the mud. We are not sure if he is the actual slaughterman, or merely the butcher, but we do learn the whereabouts of the child’s head. The victim is soon identified as Maisie Lancaster, but a visit to her parents’ house brings MacIntosh into a collision with the metaphorical runaway car of one of his previous cases.

We have the advantage over the police in that we are introduced early on to the man who dropped the suitcase from the bridge into the mud. We are not sure if he is the actual slaughterman, or merely the butcher, but we do learn the whereabouts of the child’s head. The victim is soon identified as Maisie Lancaster, but a visit to her parents’ house brings MacIntosh into a collision with the metaphorical runaway car of one of his previous cases.

When the cops investigate the house from which the young man ran, they find the second corpse of the morning, with her throat slit. She is – or rather was – Cordi Gannet. She made a decent living producing lifestyle videos for YouTube, full of cod psychology and trite advice about life improvement strategies. Her psychology degree was apparently bought mail-order from an on-line university, and when Alex Delaware gets to the scene with Milo, he remembers that he was once involved in a child custody case where Cordi Gannet was introduced as an expert witness – with disastrous consequences.

When the cops investigate the house from which the young man ran, they find the second corpse of the morning, with her throat slit. She is – or rather was – Cordi Gannet. She made a decent living producing lifestyle videos for YouTube, full of cod psychology and trite advice about life improvement strategies. Her psychology degree was apparently bought mail-order from an on-line university, and when Alex Delaware gets to the scene with Milo, he remembers that he was once involved in a child custody case where Cordi Gannet was introduced as an expert witness – with disastrous consequences. Watching the Delaware-Sturgis partnership work on a case is fascinating. Yes, by my reckoning this is the 37th in the series. No, that’s not a typo. Thirty seven since their debut in When The Bough Breaks (1985). 1985. Blimey. Amongst other ground-breaking events in that year, I read that Playboy stopped stapling its centrefolds, the first episode of Eastenders was broadcast, and Freddie Mercury stole the show at Live Aid. But I digress.

Watching the Delaware-Sturgis partnership work on a case is fascinating. Yes, by my reckoning this is the 37th in the series. No, that’s not a typo. Thirty seven since their debut in When The Bough Breaks (1985). 1985. Blimey. Amongst other ground-breaking events in that year, I read that Playboy stopped stapling its centrefolds, the first episode of Eastenders was broadcast, and Freddie Mercury stole the show at Live Aid. But I digress.

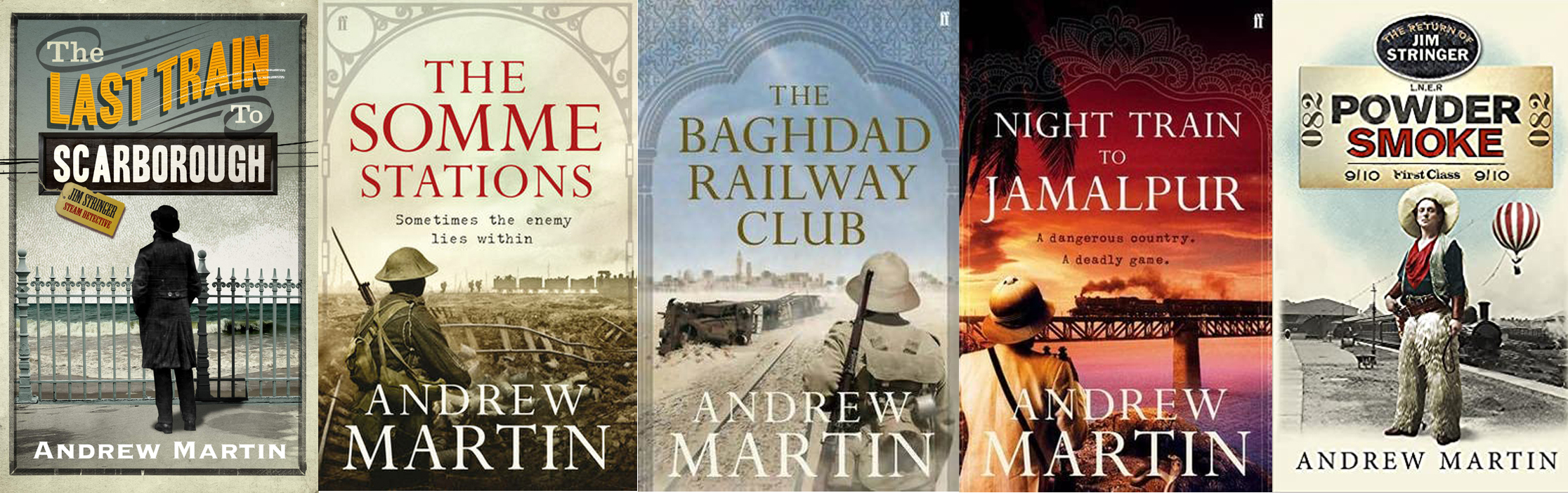

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants. Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

The team investigating the murder is led by Detective Inspector Isabel Blood, her Sergeant and a brace of DCs. They soon learn that the dead man is Kevin Spriggs, a middle-aged car mechanic, with a failed marriage behind him, an estranged son – and an argumentative temperament often fueled by drink. The murder raises many questions for Blood and her people. How did Spriggs and the person who killed him gain access to a locked house? Who hated Spriggs – admittedly not one of life’s natural charmers – enough to kill him? After all, he was something of a nobody, tolerated rather than loved by most people who knew him, but why this brutal – and mysterious – death?

The team investigating the murder is led by Detective Inspector Isabel Blood, her Sergeant and a brace of DCs. They soon learn that the dead man is Kevin Spriggs, a middle-aged car mechanic, with a failed marriage behind him, an estranged son – and an argumentative temperament often fueled by drink. The murder raises many questions for Blood and her people. How did Spriggs and the person who killed him gain access to a locked house? Who hated Spriggs – admittedly not one of life’s natural charmers – enough to kill him? After all, he was something of a nobody, tolerated rather than loved by most people who knew him, but why this brutal – and mysterious – death?

Investigating duos are always a reliable way to spin a police novel, and in this case we have Inspector Harvey Marmion and Sergeant Joe Keedy of the Metropolitan Police. Marmion is married to Ellen, with a son and daughter. Son Paul has been mentally damaged by his time on the Western Front, and has now disappeared leaving no clue as to his whereabouts, while daughter Alice – also a service police officer – is engaged to Keedy.

Investigating duos are always a reliable way to spin a police novel, and in this case we have Inspector Harvey Marmion and Sergeant Joe Keedy of the Metropolitan Police. Marmion is married to Ellen, with a son and daughter. Son Paul has been mentally damaged by his time on the Western Front, and has now disappeared leaving no clue as to his whereabouts, while daughter Alice – also a service police officer – is engaged to Keedy. Edward Marston

Edward Marston

The story begins with a murder, graphically described and, at this point in the review, it is probably pertinent to warn squeamish readers to return to the world of painless and tidy murders in Cotswold manor houses and drawing rooms, because death in this book is ugly, ragged, slow and visceral. The victim is a middle-aged woman who makes a living out of reading Tarot cards, tea leaves, crystal balls and other trinkets of the clairvoyance trade. She lives in an isolated cottage on the bleak shore of the Humber and, one evening, with a cold wind scouring in off the river, she tells one fortune too many.

The story begins with a murder, graphically described and, at this point in the review, it is probably pertinent to warn squeamish readers to return to the world of painless and tidy murders in Cotswold manor houses and drawing rooms, because death in this book is ugly, ragged, slow and visceral. The victim is a middle-aged woman who makes a living out of reading Tarot cards, tea leaves, crystal balls and other trinkets of the clairvoyance trade. She lives in an isolated cottage on the bleak shore of the Humber and, one evening, with a cold wind scouring in off the river, she tells one fortune too many. “She has found herself some mornings with little horseshoe grooves dug into the soft flesh of her palms. Sometimes her wrists and elbows ache until lunchtime. She sleeps like a toppled pugilist: a Pompeian tragedy. She sees such terrible things in the few snatched moments of unconsciousness.”

“She has found herself some mornings with little horseshoe grooves dug into the soft flesh of her palms. Sometimes her wrists and elbows ache until lunchtime. She sleeps like a toppled pugilist: a Pompeian tragedy. She sees such terrible things in the few snatched moments of unconsciousness.”

Nikki Hardcastle

Nikki Hardcastle