I have a close friend who keeps himself fit by walking London suburbs searching charity shops for rare – and sometimes valuable – crime novels. On one particular occasion he was spectacularly successful with a rare John le Carré first edition, but he is ever alert to particular fads and enthusiasms of mine. Since I “discovered” PM Hubbard, thanks to a tip-off from none other than Phil Rickman, my friend has been on the lookout for for anything by this English writer (1910 – 1980) and his latest find, A Hive of Glass is a Panther Crimeband paperback, published in 1966. This was a year after Michael Joseph published the first edition (left), and Hubbard fans could have bought the paperback for the princely sum of 3s/6d (about 16.5p in modern money).

I have a close friend who keeps himself fit by walking London suburbs searching charity shops for rare – and sometimes valuable – crime novels. On one particular occasion he was spectacularly successful with a rare John le Carré first edition, but he is ever alert to particular fads and enthusiasms of mine. Since I “discovered” PM Hubbard, thanks to a tip-off from none other than Phil Rickman, my friend has been on the lookout for for anything by this English writer (1910 – 1980) and his latest find, A Hive of Glass is a Panther Crimeband paperback, published in 1966. This was a year after Michael Joseph published the first edition (left), and Hubbard fans could have bought the paperback for the princely sum of 3s/6d (about 16.5p in modern money).

In his best works Hubbard gives us an ostensibly benevolent rural England; small towns, pretty villages, ancient woodlands, the warm stone of village churches and old parkland (always with a time-weathered manor or house at its centre). This England, however, invariably has something menacing going on behind the façade. Not simply, it must be said, in a cosy Midsomer Murders fashion, but in a much more disturbing way. Hubbard doesn’t engage with the overtly supernatural, but he teases us with suggestions that there might – just might – be something going on, an uneasy sense of what Hamlet was referring to in his celebrated remark to Horatio in Hamlet (1.5.167-8)

In A Hive of Glass, a gentleman of undisclosed means, Jonnie Slade, pursues his lifelong interest in antique glassware. He is an auctioneers’ and dealer’ worst nightmare, with an encyclopaedic knowledge of styles, techniques – and market value. He becomes aware of an important piece of sixteenth century glass – to the uninitiated, not much more than a glass saucer – whose provenance includes the crucial involvement of none other than Gloriana herself. Looking to find more information on the tazza, made by the legendary Giacomo Verzelini, he visits an elderly man whose knowledge of the period is legendary, only to find him dead in his study. With only a couple of amateurish photographs and a diary entry to guide him, Slade drives out of London to the remote village of Dunfleet.

In Dunfleet he meets a young woman called Claudia. Their erotically charged relationship is central to the story, as is the fact that she is the niece of Elizabeth Barton, the elderly woman in whose house the tazza is hidden. Even to himself, Slade’s motives are unclear. Does he want to steal the tazza? Does he just want to confirm its location? Does he suspect Claudia of attempting to defraud her aunt?

Seldom, however, can a treasure have been protected by two more menacing guardians in Aunt Elizabeth and her maid-of-all-work Coster. Remember Blind Pew, one of the more terrifying villains of literature? Remember Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and the decades that it was hidden from sight? With a freedom that simply would not escape the censor today, Hubbard (right) taps into our visceral fear of abnormality and disability. Hubbard has created two terrifying women and a dog which is makes Conan Doyles celebrated hound Best In Show. The dog first:

Seldom, however, can a treasure have been protected by two more menacing guardians in Aunt Elizabeth and her maid-of-all-work Coster. Remember Blind Pew, one of the more terrifying villains of literature? Remember Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and the decades that it was hidden from sight? With a freedom that simply would not escape the censor today, Hubbard (right) taps into our visceral fear of abnormality and disability. Hubbard has created two terrifying women and a dog which is makes Conan Doyles celebrated hound Best In Show. The dog first:

“It was pinky-white all over and looked quite naked and scrofulous. Even from sideways its eyes were almost invisible behind puckered pink lids. It waddled and wheezed like a fat dog, but you could see most of the bones under the hanging skin. Its smell went past me as it it walked.”

Attached to the vile animal is blind Aunt Elizabeth:

“On the end of the lead came a long black glove and behind it Claudia’s Aunt Elizabeth. I had no idea, seeing her through a curtained window like that, how tall she was. She must have been all of six foot and her elaborately coiled hair put as much on her height as a policeman’s helmet…Her feet were as big as the rest of her. The skin was grey but clear and glossy and her smile, as she passed me, came back almost under her ear.”

Aunt Elizabeth’s maid, Coster, is equally terrifying. She is stone deaf, huge, and mutters to herself in a constant high-pitched monotone:

“She was a tall soldierly woman, with a frame much too big for that little thin, continuous voice. She wore a bunchy black skirt with a long apron over it and some sort of blue and white blouse over her great square top half. As it was, I could hear a continuous stream of sound, inflected and articulated like speech, but defying my analysis.:

I would have turned tail and ran as far from this trio of horrors as fast as my legs could carry me, but Slade is made of sterner stuff, and he stays to discover the hiding place of the Verzelini tazza, but not without considerable cost to his own sanity and sense of well-being.

A Hive of Glass is available as a Murder Room reprint, or you can search charity shops for an original version. For more on PM Hubbard and his novels, follow this link.

Mr Bulmer is a uniquely repulsive little man who manages a dry cleaning shop in Mayfair, and uses the opportunity of searching through the jackets and trouser pockets of wealthy individuals to service his own very profitable blackmail industry. His malignant little sideline has provided him with a regular income – and driven at least one of his victims to suicide. When he seizes upon what he sees as the opportunity of a lifetime, he is unaware that is about to be snared by his own hook. John Bingham, in addition to being a writer of distinction, was also a highly placed official in British Intelligence operations.

Mr Bulmer is a uniquely repulsive little man who manages a dry cleaning shop in Mayfair, and uses the opportunity of searching through the jackets and trouser pockets of wealthy individuals to service his own very profitable blackmail industry. His malignant little sideline has provided him with a regular income – and driven at least one of his victims to suicide. When he seizes upon what he sees as the opportunity of a lifetime, he is unaware that is about to be snared by his own hook. John Bingham, in addition to being a writer of distinction, was also a highly placed official in British Intelligence operations. Crispin, aka Robert Bruce Montgomery, is best known for his Gervase Fen novels but here he spins a delightfully black tale of a struggling writer whose hospitality is impinged upon by a pair of runaways, both seeking a new life away from their spouses. Crispin intersperses the narrative with vivid accounts of a writer desperately searching for the words which will bring his latest novel to life. Sadly for the would-be lovers, their fate is to be organic fertiliser for Mr Bradley’s vegetable plot.

Crispin, aka Robert Bruce Montgomery, is best known for his Gervase Fen novels but here he spins a delightfully black tale of a struggling writer whose hospitality is impinged upon by a pair of runaways, both seeking a new life away from their spouses. Crispin intersperses the narrative with vivid accounts of a writer desperately searching for the words which will bring his latest novel to life. Sadly for the would-be lovers, their fate is to be organic fertiliser for Mr Bradley’s vegetable plot. Davidson’s internationally themed thrillers were his bread and butter, but we must not forget that he was a writer of immense sensitivity with a wide range of influences. His own upbringing as a child of a hard-scrabble Polish-Jewish family might have made it unlikely that he would compose a chilling tale of murder on the banks of s Scottish river frequented only by rich Englishmen with the money to buy the rights to snare incoming salmon. A man whose sexual abilities have been devastated by a potentially fatal illness plans revenge on a friend whose libido remains undiminished. The denouement takes place on the banks of Scotland’s sacred salmon river – the Spey.

Davidson’s internationally themed thrillers were his bread and butter, but we must not forget that he was a writer of immense sensitivity with a wide range of influences. His own upbringing as a child of a hard-scrabble Polish-Jewish family might have made it unlikely that he would compose a chilling tale of murder on the banks of s Scottish river frequented only by rich Englishmen with the money to buy the rights to snare incoming salmon. A man whose sexual abilities have been devastated by a potentially fatal illness plans revenge on a friend whose libido remains undiminished. The denouement takes place on the banks of Scotland’s sacred salmon river – the Spey. Colin Dexter? Cue Oxford, an irascible senior policeman, pints of English beer and crossword puzzles? Think on. When this story was published, Dexter was already four books into his Inspector Morse series, but the TV adaptations were still six years away. In this tale, Dexter takes us to, of all places, rural America, where a coach load of middle-aged and elderly tourists take a rest stop at the eponymous wayside hotel. The action is centred around a game of vingt-et-un, designed to empty the wallets of the gullible travellers. Dexter describes a scam-within-a -scam -but saves until the last few paragraphs a chilling finale in which the scammer becomes the scammed.

Colin Dexter? Cue Oxford, an irascible senior policeman, pints of English beer and crossword puzzles? Think on. When this story was published, Dexter was already four books into his Inspector Morse series, but the TV adaptations were still six years away. In this tale, Dexter takes us to, of all places, rural America, where a coach load of middle-aged and elderly tourists take a rest stop at the eponymous wayside hotel. The action is centred around a game of vingt-et-un, designed to empty the wallets of the gullible travellers. Dexter describes a scam-within-a -scam -but saves until the last few paragraphs a chilling finale in which the scammer becomes the scammed. People might forget that Antonia Fraser, as well as being the daughter of Lord Longford the widow of Harold Pinter and a superb historical biographer, is no slouch when it comes to crime fiction. Here, she taps into that strange love affair that English people have with their dogs. Richard Gavin is a successful barrister (is there ever another sort?) who has kept his upper lip stiff and tremble-free during the death of his first wife, and remarried. The new lady of the Gavin household is Paulina – young. bright and adorable. Her judgment, however is brought into question, when her decision to put an aged, smelly and incontinent spaniel out of its misery coincides with Richard opening an ominous letter from his London doctor.

People might forget that Antonia Fraser, as well as being the daughter of Lord Longford the widow of Harold Pinter and a superb historical biographer, is no slouch when it comes to crime fiction. Here, she taps into that strange love affair that English people have with their dogs. Richard Gavin is a successful barrister (is there ever another sort?) who has kept his upper lip stiff and tremble-free during the death of his first wife, and remarried. The new lady of the Gavin household is Paulina – young. bright and adorable. Her judgment, however is brought into question, when her decision to put an aged, smelly and incontinent spaniel out of its misery coincides with Richard opening an ominous letter from his London doctor. This is the most shocking and slap-in-the-face story in the collection. I would go as far as to suggest that it would not have been written – let alone published – today, with our heightened awareness of child abuse and domestic violence. As an account of casual violence, domestic cruelty, alcohol abuse – and the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic church – it makes for uncomfortable reading. Highsmith’s misanthropy can never have been more glaringly or honestly displayed. her publisher wrote:

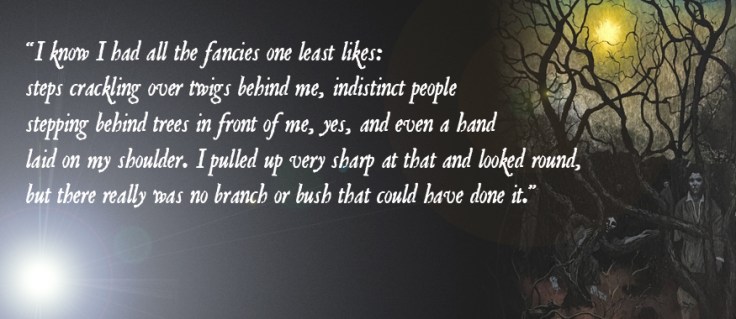

This is the most shocking and slap-in-the-face story in the collection. I would go as far as to suggest that it would not have been written – let alone published – today, with our heightened awareness of child abuse and domestic violence. As an account of casual violence, domestic cruelty, alcohol abuse – and the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic church – it makes for uncomfortable reading. Highsmith’s misanthropy can never have been more glaringly or honestly displayed. her publisher wrote: Like Hubbard’s longer works, which are examined in this feature, a dream-like quality pervades this story, but the dreams are not necessarily pleasant ones. The first words are:

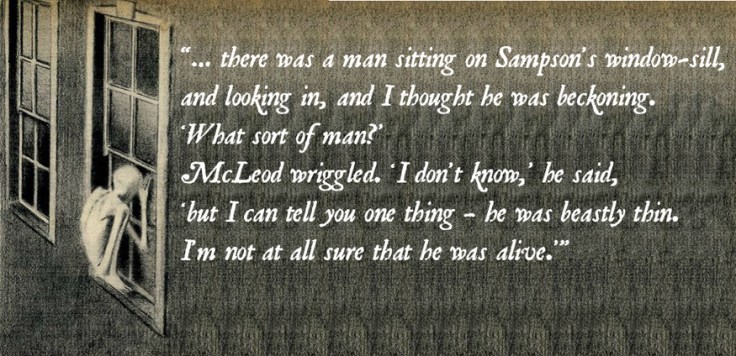

Like Hubbard’s longer works, which are examined in this feature, a dream-like quality pervades this story, but the dreams are not necessarily pleasant ones. The first words are: This exquisite masterpiece tells of a nameless girl, an orphan, who is brought up in a loveless terraced house in east London, the home of her Uncle Victor and Aunt Gladys. Her only joy is the adjacent cemetery which becomes a place of mystical and endless attraction:

This exquisite masterpiece tells of a nameless girl, an orphan, who is brought up in a loveless terraced house in east London, the home of her Uncle Victor and Aunt Gladys. Her only joy is the adjacent cemetery which becomes a place of mystical and endless attraction:

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure. The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

Flush As May (1963) takes its title from a soliloquy by Hamlet, and Hubbard sets the piece in an ostensibly idyllic rural England, contemporary with the time of the novel’s publication. Margaret Canting is an Oxford undergraduate staying in the nearby village of Lodstone She takes it upon herself to see in May Morning, not by carolling from the top of a church tower, but with a dawn stroll. Her idyll is interrupted when she finds the corpse of a man, sleeping his final sleep against the grassy bank at the edge of a field.

Flush As May (1963) takes its title from a soliloquy by Hamlet, and Hubbard sets the piece in an ostensibly idyllic rural England, contemporary with the time of the novel’s publication. Margaret Canting is an Oxford undergraduate staying in the nearby village of Lodstone She takes it upon herself to see in May Morning, not by carolling from the top of a church tower, but with a dawn stroll. Her idyll is interrupted when she finds the corpse of a man, sleeping his final sleep against the grassy bank at the edge of a field.

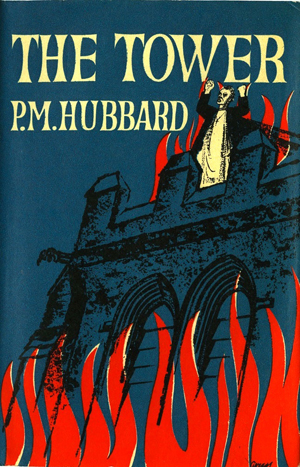

The Tower (1968) begins with Hubbard tipping his hat in a gentlemanly fashion in the direction of a lady. The lady is none other than Dorothy L Sayers. Her masterpiece (other opinions are available), The Nine Tailors, begins with Bunter and Lord Peter abandoning their car in a snowy ditch outside a remote Fenland village. So it is that John Smith, the central character in The Tower, finds his car refusing to travel an inch further on an inky black night, a mile or so outside the village of Coyle. That, however is pretty much where the homage ends. Coyle is a far more sinister place that Fenchurch St Peter, and its vicar, Father Freeman, is infinitely less benevolent than dear old Reverend Venables.

The Tower (1968) begins with Hubbard tipping his hat in a gentlemanly fashion in the direction of a lady. The lady is none other than Dorothy L Sayers. Her masterpiece (other opinions are available), The Nine Tailors, begins with Bunter and Lord Peter abandoning their car in a snowy ditch outside a remote Fenland village. So it is that John Smith, the central character in The Tower, finds his car refusing to travel an inch further on an inky black night, a mile or so outside the village of Coyle. That, however is pretty much where the homage ends. Coyle is a far more sinister place that Fenchurch St Peter, and its vicar, Father Freeman, is infinitely less benevolent than dear old Reverend Venables.