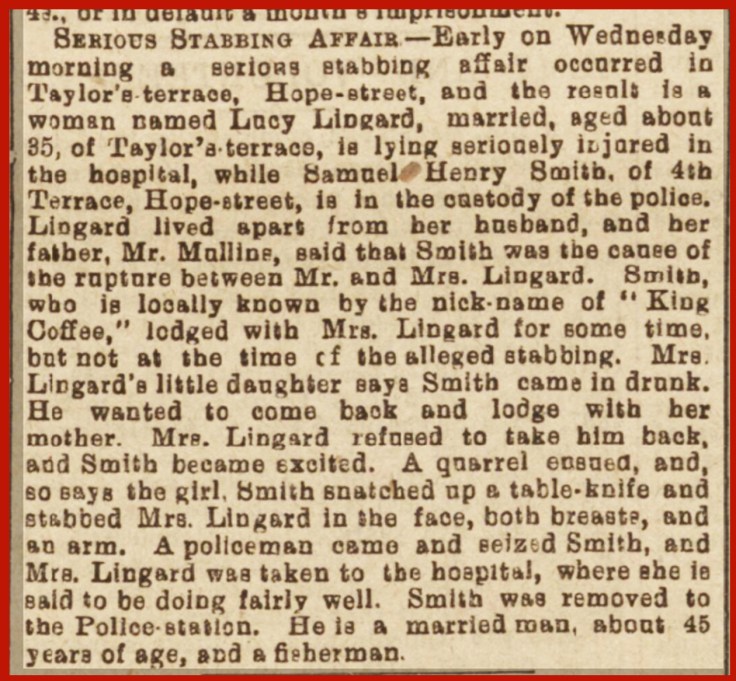

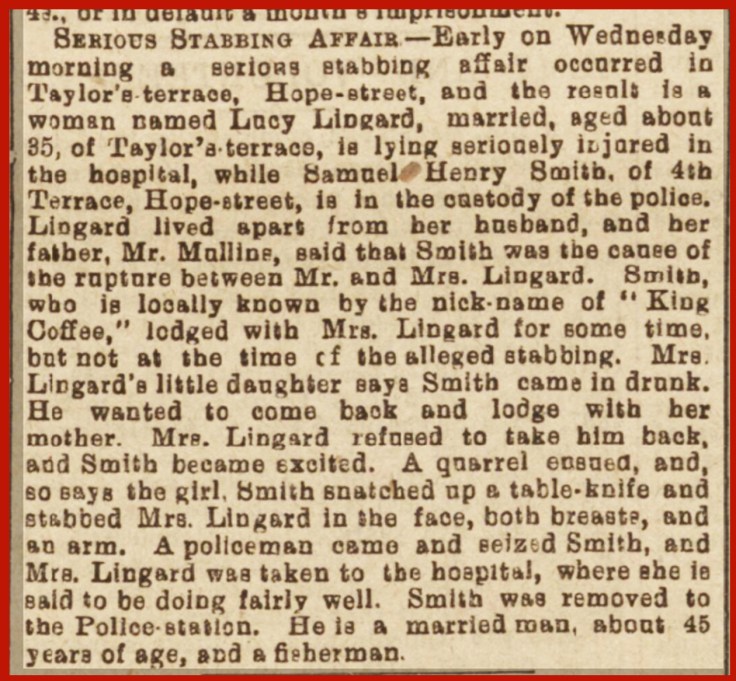

SO FAR: Grimsby, 18th November 1902. Lucy Lingard is separated from her husband John. She and her children live in Hope Street, and she has been in a relationship with Samuel Harold Smith (Harry), a trawlerman. He has returned from sea, and the couple have spent the afternoon and evening drinking and arguing. Smith has hit Lucy several times, but they return to their house, both drunk. A newspaper reported what happened next.

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

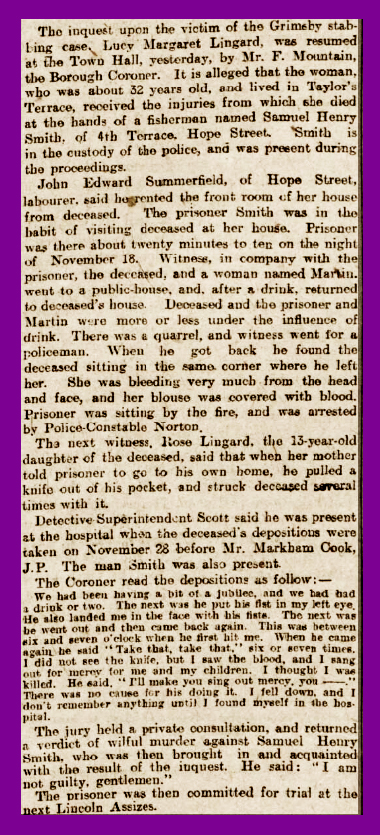

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

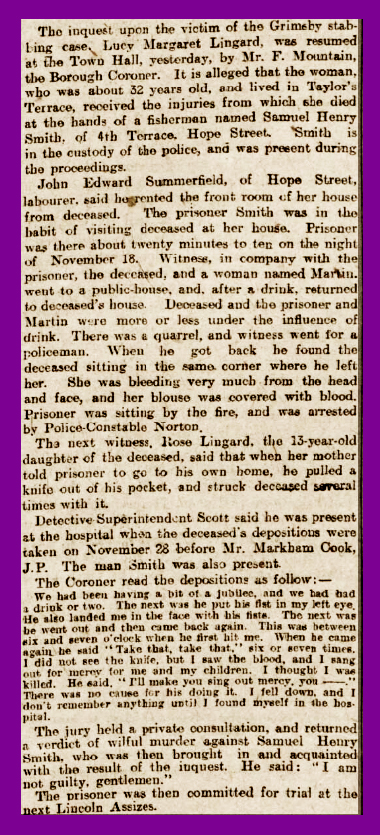

“Dr Harold Freeth, house surgeon at the Hospital, gave evidence to the effect that the deceased died in the Hospital from exhaustion, following on from injuries, which he described. There were eleven incised wounds in all, chiefly on the chest and the left arm. One of the most serious wounds was that on the upper side of the left breast, and penetrated through the first rib into the chest cavity. The deceased had lost a great deal of blood. Witness had made a post-mortem examination. The wound which penetrated the chest had set up acute inflammation, and there was also inflammation of the pericardium. In reply to a juryman, the witness said the deceased’s organs were quite healthy before the injuries were inflicted.”

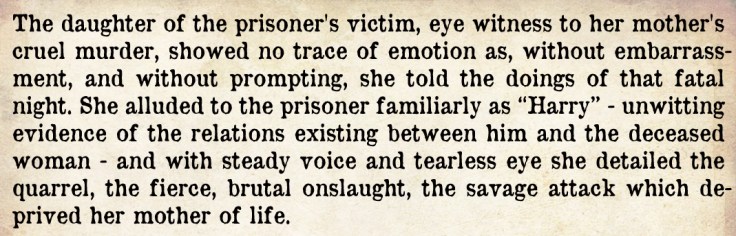

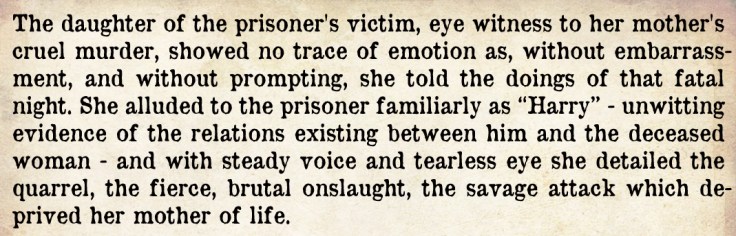

Bizarrely, despite the eye-witness testimony of Lucy Lingard’s daughter, who had witnessed the attack, and the fact that he had admitted his guilt when arrested, Smith pleaded not guilty. Another newspaper reported on young Rose’s demeanour.

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

“The Lincolnshire Assizes were resumed yesterday before Justice Kennedy. Samuel Henry Smith, aged 45, fisherman, was indicted for the wilful murder of Lucy Margaret Lingard. at Grimsby, on the 18th November last. Mr Etherington Smith and Mr Lawrence appeared for the prosecution, and at the request of the Judge Mr Bonner undertook the defence. The case was sordid one. The deceased woman lived apart from her husband at 3, Taylor’s Terrace, Hope Street, Grimsby, and the accused had been in the habit of staying with her. On November 18th last the couple were out together during the afternoon, and on their return had some words, and the prisoner struck the woman. Afterwards they again went out, and when they returned late at night with a lodger and another woman, they were the worse for drink. The quarrel was resumed after a time, and, according to the evidence of the woman’s thirteen-year-old daughter, the accused took out a knife, and, rushing at the deceased, stabbed her several times. She died in the hospital on the following Sunday. On the prisoner’s behalf, Mr Bonner suggested that the jury would be justified in finding him guilty of manslaughter. The crime was undoubtedly due to drink, and he submitted that at the time of its commission the prisoner was not in condition to exercise any discretion as to the result of what he was doing. The jury found the prisoner guilty of Wilful Murder,” and he was sentenced to death.”

Smith’s legal team had applied to the Home Secretary, Viscount Chilston, for a reprieve, but he was not minded to be merciful. Likewise a petition set up by residents of Smith’s home town, Brixham, was ignored. On Tuesday 10th March, Samuel Henry Smith was marched to the scaffold by the executioner, William Billington (left). The role of state executioners was often kept within families. Just as the Pierrepoint family had several hangmen – Henry, Thomas and Albert, William Billington took over the job – along with brothers John and Thomas – when their father, James, died in 1901. Newspaper reporters, at this time, were still officially allowed to witness executions first hand, but in practice, most prison governors (and the hangmen) preferred if they didn’t, due to sensationalised and lurid accounts of the prisoners’ last moments. Whether the reporter from the LIncolnshire Chronicle saw the end of Samuel Henry Smith with his own eyes, or simply used his imagination, we do not know:

“According to recent Home Office regulations the black flag is not now displayed and all that told of the end was the tolling of the prison bell just after hour had struck. Inside the Prison, where there were only officials, the scene was impressively quiet. Wm. Billington the executioner, and his brother John, had arrived on the previous night. Early on the fateful morn the Rev. C.H. Scott visited the condemned man, who listened to his ministrations with attention and apparent gratitude. At ten minutes to eight o’clock County Under-Sheriff (Mr. Chas. Scorer) entered the cell, and approaching Smith requested him to prepare for execution. To all appearance he remained quite calm, and with a steady voice intimated that he was prepared to meet his death. Quietly he submitted himself to the executioner for the necessary pinioning process, and walked unfalteringly to the scaffold, and within two minutes all was over. Billington allowed a drop of 7ft. 3in. To the witnesses death appeared to be absolutely instantaneous and there was scarce a motion of the rope after the body disappeared from sight in the space below the drop.”

All that remained was for Samuel Henry Smith’s body to be buried in the gaol cemetery, along with dozens of other executed killers, and his name to be entered in the official record book.

FOR MORE LINCOLNSHIRE MURDERS, CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Hope Street in Grimsby was cleared of its terraces in the late 1960s (pictured above, thanks to Hope Street History), but a late 19th century map shows back-to-back houses opening directly onto the street, and every so often there would courtyards, each open area being surrounded on three sides by further dwellings. For those interested in the history of Hope Street, there is a Facebook page that gives access to an excellent pdf document describing the history of the street. That link is

Hope Street in Grimsby was cleared of its terraces in the late 1960s (pictured above, thanks to Hope Street History), but a late 19th century map shows back-to-back houses opening directly onto the street, and every so often there would courtyards, each open area being surrounded on three sides by further dwellings. For those interested in the history of Hope Street, there is a Facebook page that gives access to an excellent pdf document describing the history of the street. That link is

One of Kennedy’s chief scalps was serial killer Pauline Tosh, who now faces spending the rest of her days in a remote high security jail. Out of the blue, Tosh requests a visit from the officer who ended her murderous career, and what she reveals sets off a search for a body. When it is discovered, and is revealed to be that of the long-since missing Freya Sutherland, what is in effect a massive cold-case-murder hunt is put into place.

One of Kennedy’s chief scalps was serial killer Pauline Tosh, who now faces spending the rest of her days in a remote high security jail. Out of the blue, Tosh requests a visit from the officer who ended her murderous career, and what she reveals sets off a search for a body. When it is discovered, and is revealed to be that of the long-since missing Freya Sutherland, what is in effect a massive cold-case-murder hunt is put into place. As with all good crime writers, Halliday (right) leads us up the garden path, and killers (plural) are actually found, but the solution is surprising and beautifully complex. Oh yes, I almost forgot. From his bio, GR Halliday is a lover of cats, so if you share his passion, there are cats in this story. Several of them.

As with all good crime writers, Halliday (right) leads us up the garden path, and killers (plural) are actually found, but the solution is surprising and beautifully complex. Oh yes, I almost forgot. From his bio, GR Halliday is a lover of cats, so if you share his passion, there are cats in this story. Several of them.

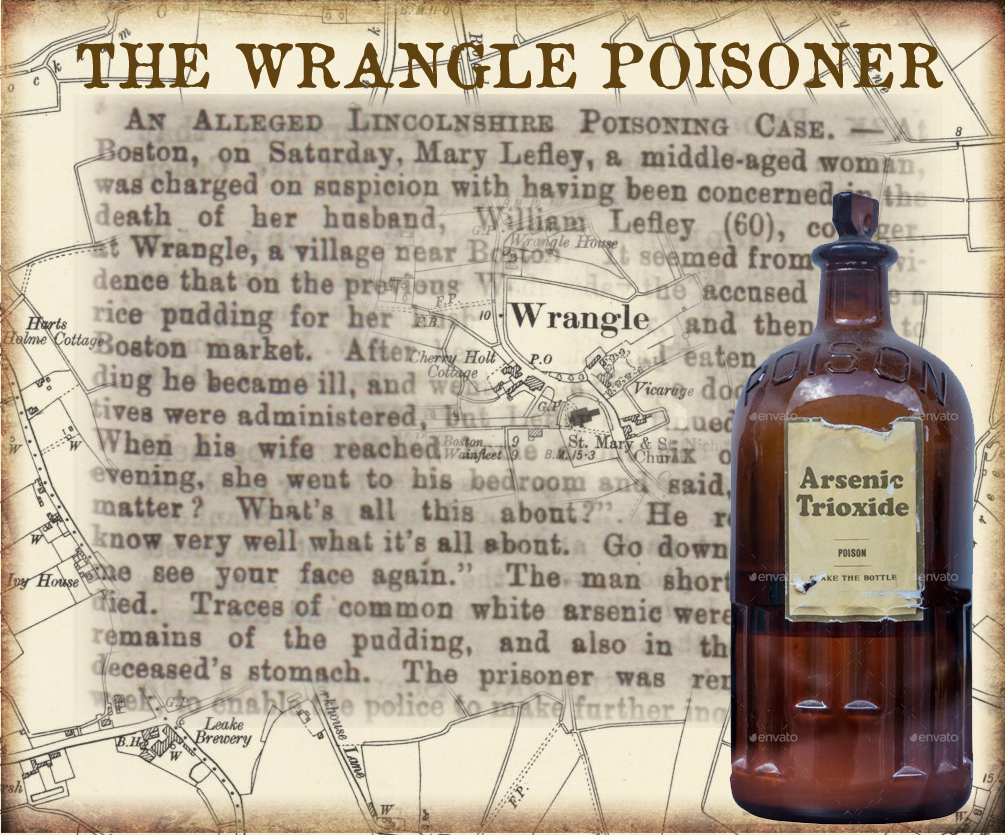

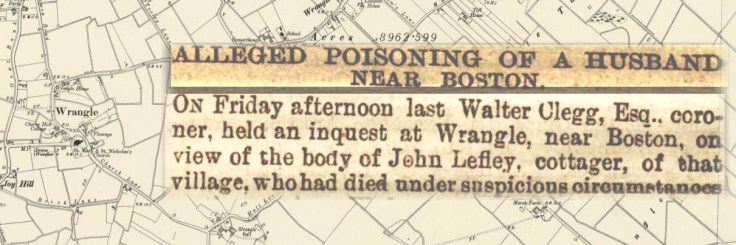

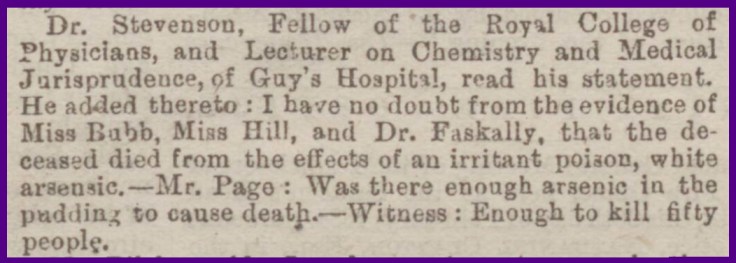

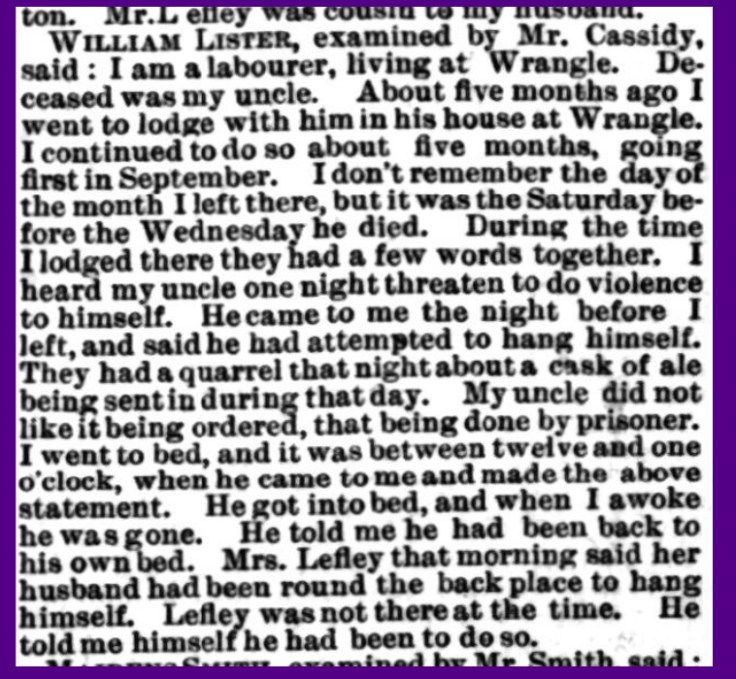

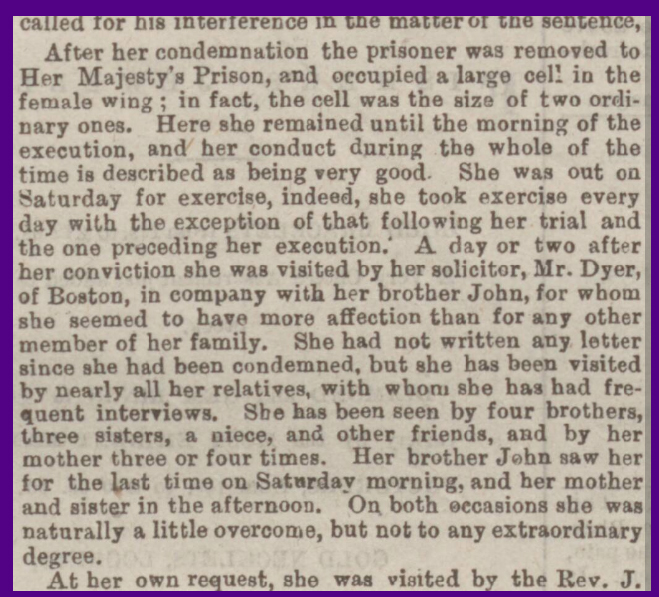

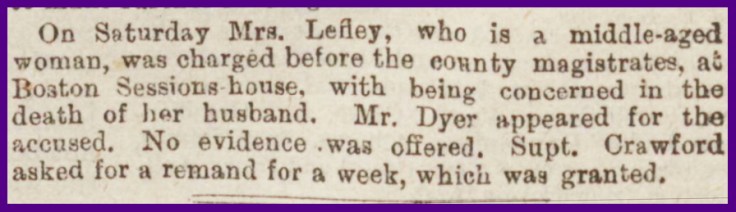

Based mainly on the question, “Who else could have done it?” Mary Lefley was sent for trial at the Lincoln Assizes. She was to appear before Mr Justice North. Mary’s defence barrister made the point:

Based mainly on the question, “Who else could have done it?” Mary Lefley was sent for trial at the Lincoln Assizes. She was to appear before Mr Justice North. Mary’s defence barrister made the point:

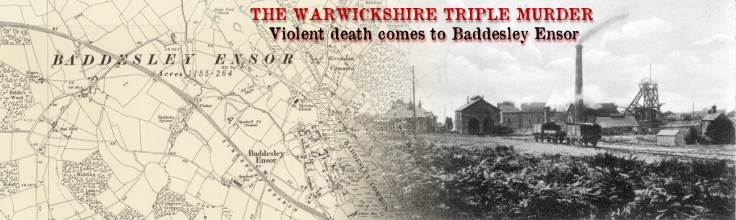

The rest of this grim tale almost tells itself. George Place, apparently unrepentant throughout, was taken through the usual procedure of Coroner’s inquest, Magistrates’ court, and then sent to the Autumn Assizes at Warwick in December. Presiding over the court was Richard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, and the trial was brief. Despite the obligatory plea from Place’s defence team that he was insane when he pulled the trigger three times in that Baddesely Ensor cottage, the jury were having none of it, and the judge donned the black cap, sentencing George Place to death by hanging. The trial was at the beginning of December, the date fixed for the execution was fixed for 13th December, but George Place did not meet his maker until 30th December. It is idle to speculate about quite what kind of Christmas Place spent in his condemned cell, but for some reason, during his incarceration, he had converted to Roman Catholicism. It seems he left this world with more dignity than he had allowed his three victims. The executioner was Henry Pierrepoint.

The rest of this grim tale almost tells itself. George Place, apparently unrepentant throughout, was taken through the usual procedure of Coroner’s inquest, Magistrates’ court, and then sent to the Autumn Assizes at Warwick in December. Presiding over the court was Richard Webster, 1st Viscount Alverstone, and the trial was brief. Despite the obligatory plea from Place’s defence team that he was insane when he pulled the trigger three times in that Baddesely Ensor cottage, the jury were having none of it, and the judge donned the black cap, sentencing George Place to death by hanging. The trial was at the beginning of December, the date fixed for the execution was fixed for 13th December, but George Place did not meet his maker until 30th December. It is idle to speculate about quite what kind of Christmas Place spent in his condemned cell, but for some reason, during his incarceration, he had converted to Roman Catholicism. It seems he left this world with more dignity than he had allowed his three victims. The executioner was Henry Pierrepoint.