Author Leona Deakin

Dr Augusta Bloom is a psychologist who specialises in the criminal mind. Her business partner is Marcus Jameson, a former British intelligence agent. Bloom is often employed by the police as a consultant when a particular case demands her particular skill-set. The killers Bloom is requested to track down have struck twice, leaving only burnt matches as a clue. I use the plural ‘killers’ advisedly, as we know they are a team, but Bloom and the police have yet to discover this.

Dr Augusta Bloom is a psychologist who specialises in the criminal mind. Her business partner is Marcus Jameson, a former British intelligence agent. Bloom is often employed by the police as a consultant when a particular case demands her particular skill-set. The killers Bloom is requested to track down have struck twice, leaving only burnt matches as a clue. I use the plural ‘killers’ advisedly, as we know they are a team, but Bloom and the police have yet to discover this.

As with the previous novels, there are two parallel plots in The Imposter. One involves Seraphine Walker who is, if you will, Moriarty to Bloom’s Holmes. Walker, despite being clinically psychopathic, is not overtly criminal, but has recruited all kinds of people who most certainly are. She heads up an organisation which, to those who enjoy a good conspiracy theory, is rather like a fictional World Economic Forum, peopled by shadowy but powerful influencers from across the globe, united by a hidden agenda The relationship between Bloom and Walker has an added piquancy because they were once doctor and patient. The backstory also involves someone we met in a previous novel – the disgraced former Foreign Secretary Gerald Porter, a ruthless man who is now happily bent on evil, unimpeded by the constraints of being a government minister with the eyes of the world on him.

Augusta Bloom is an interesting creation. She is a loner, and not someone who finds personal relationships easy, not with Marcus Jameson nor with her notional boss, DCI Mirza, who is deeply sceptical about Bloom’s insights. When the police finally join all the dots, they realise that rather than two killings, there have probably been as many as eleven, which ramps up the pressure on Bloom and Jameson. Leona Deakin, (right) as one might expect from a professional psychologist, has constructed an complex relationship between Bloom, Walker and Jameson. As readers, we are not spoon-fed any moral certainties about the trio. Rather, we infer that their boundaries are, perhaps, elastic. As John Huston (as Noah Cross) said in Chinatown:

Augusta Bloom is an interesting creation. She is a loner, and not someone who finds personal relationships easy, not with Marcus Jameson nor with her notional boss, DCI Mirza, who is deeply sceptical about Bloom’s insights. When the police finally join all the dots, they realise that rather than two killings, there have probably been as many as eleven, which ramps up the pressure on Bloom and Jameson. Leona Deakin, (right) as one might expect from a professional psychologist, has constructed an complex relationship between Bloom, Walker and Jameson. As readers, we are not spoon-fed any moral certainties about the trio. Rather, we infer that their boundaries are, perhaps, elastic. As John Huston (as Noah Cross) said in Chinatown:

“You see, Mr. Gittes, most people never have to face the fact that at the right time and the right place, they’re capable of anything.”

Each of the trio – Bloom, Jameson and Walker – has a certain dependence on the two others, but Deakin keeps it open and enigmatic, leaving all plot options open to her. This symbiotic relationship has led to Augusta Bloom taking an industry – standard test to discover if she is herself a *psychopath. To her relief, although she is marking her own paper, she doesn’t tick enough boxes.

*Psychopathy, sometimes considered synonymous with sociopathy, is characterized by persistent antisocial behavior, impaired empathy and remorse, and bold, disinhibited, and egotistical traits.

Finally, Bloom cracks the mystery, Mirza and Jameson see the light, and we readers realise that Leona Deakin has been pulling the wool over our eyes for nearly 300 pages. There is a tense and violent finale, and this clever and engaging novel ends with us looking forward to the next episode in this excellent series.

The Imposter is published by Penguin and is available in paperback and Kindle now. For reviews of the three previous novels in the series, click the links below.

Tim Yates’s life

Tim Yates’s life

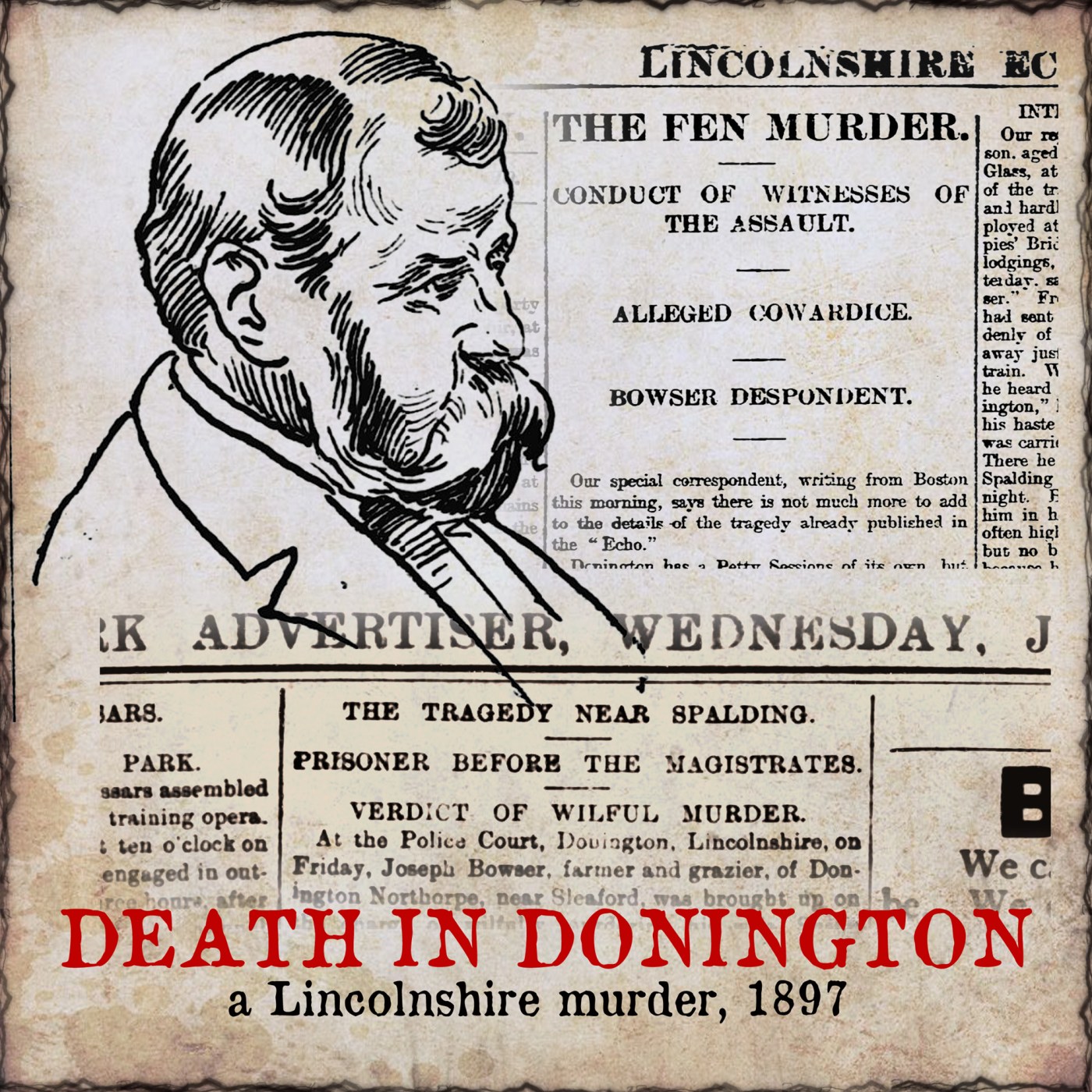

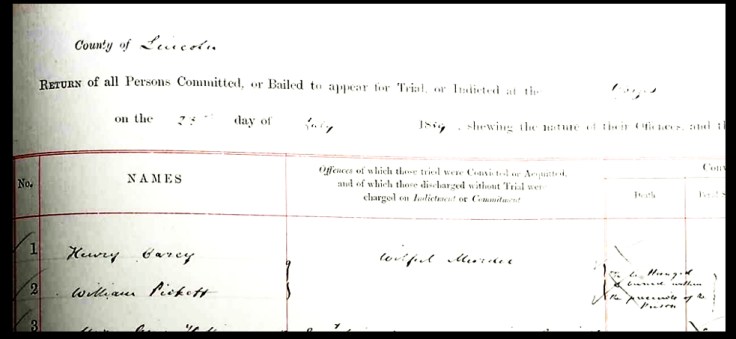

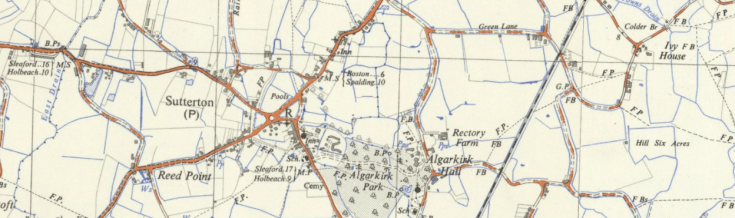

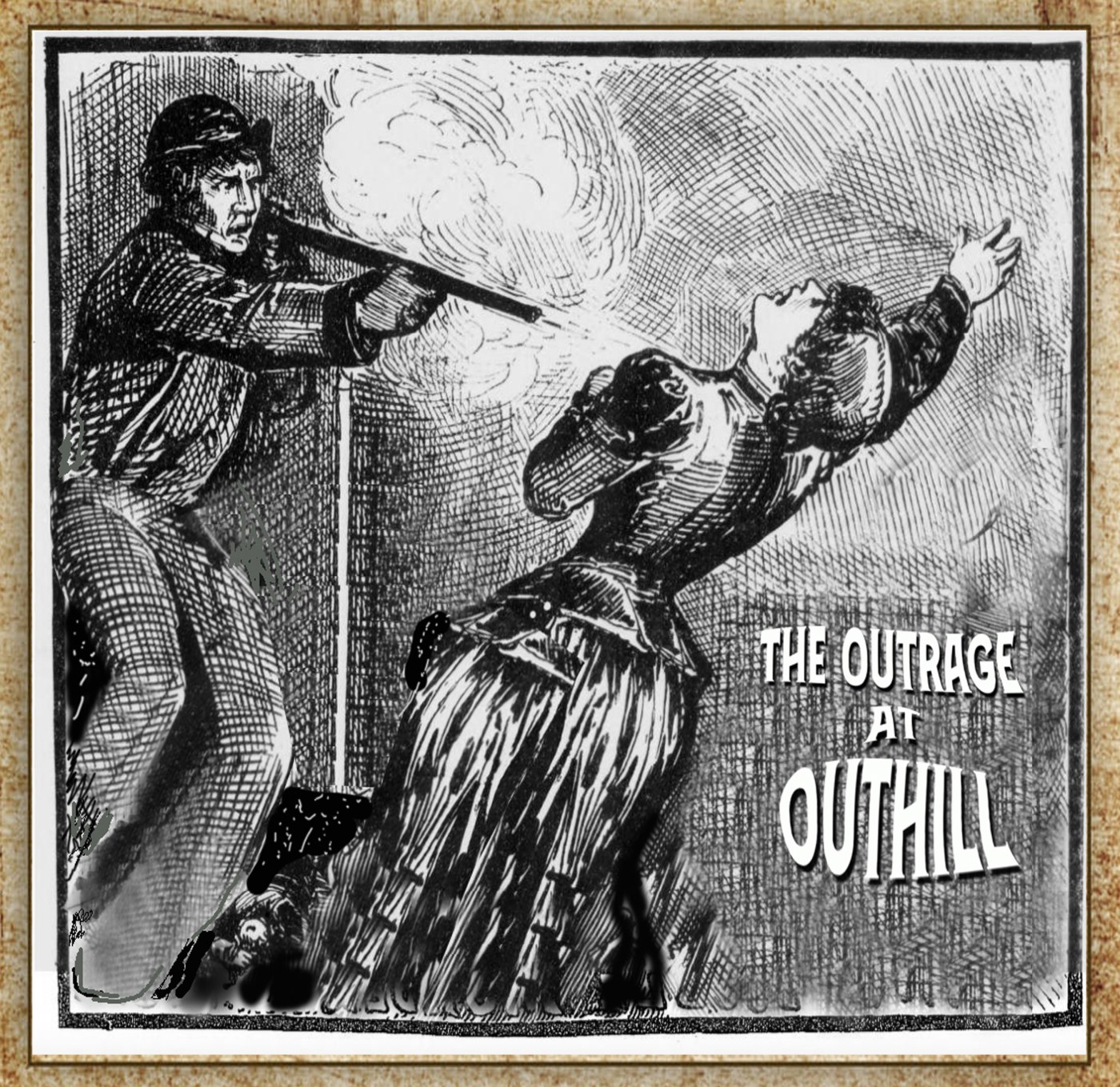

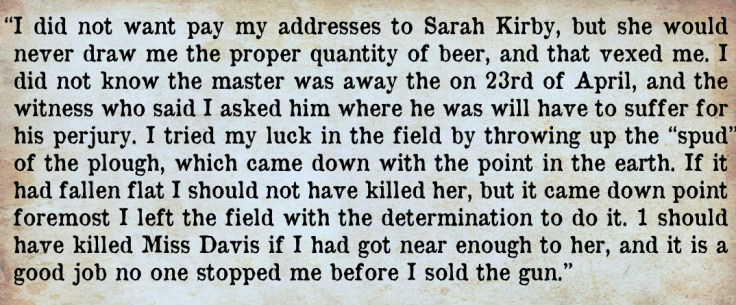

SO FAR: 23rd April, 1862, rural Warwickshire, and a 21 year old ploughman, George Gardner, employed by farmer Davis Edge at Outhill Farm, near Studley, has shot 24 year-old Sarah Kirby, employed by Edge as a domestic servant. Gardner’s peculiar state of mind before killing Sarah Kirby could almost be described as existential, in that it seemed to recognise neither logic nor the law – just his own obsession. He did, however, seem to have acknowledged the presence of chance. He had been uncertain that morning about killing Sarah Kirby, so he adopted a rural version of tossing a coin. Ploughmen used a hand-tool known as a “spud”. It was basically a flat blade, usually mounted on a wooden handle, (left} and used for clearing earth from the blades of the plough. Gardner decided to toss the tool in the air, and if it landed blade first, then Sarah Kirby would die. It did, and so did the young woman.

SO FAR: 23rd April, 1862, rural Warwickshire, and a 21 year old ploughman, George Gardner, employed by farmer Davis Edge at Outhill Farm, near Studley, has shot 24 year-old Sarah Kirby, employed by Edge as a domestic servant. Gardner’s peculiar state of mind before killing Sarah Kirby could almost be described as existential, in that it seemed to recognise neither logic nor the law – just his own obsession. He did, however, seem to have acknowledged the presence of chance. He had been uncertain that morning about killing Sarah Kirby, so he adopted a rural version of tossing a coin. Ploughmen used a hand-tool known as a “spud”. It was basically a flat blade, usually mounted on a wooden handle, (left} and used for clearing earth from the blades of the plough. Gardner decided to toss the tool in the air, and if it landed blade first, then Sarah Kirby would die. It did, and so did the young woman.

Gardner had one further misfortune. His executioner was none other than George Smith (right), a former criminal and noted drunk, known – with rough humour – as The Dudley Throttler. This was to be a public execution, and a perfectly respectable form of cheap entertainment at the time. A reporter described the scene:

Gardner had one further misfortune. His executioner was none other than George Smith (right), a former criminal and noted drunk, known – with rough humour – as The Dudley Throttler. This was to be a public execution, and a perfectly respectable form of cheap entertainment at the time. A reporter described the scene: