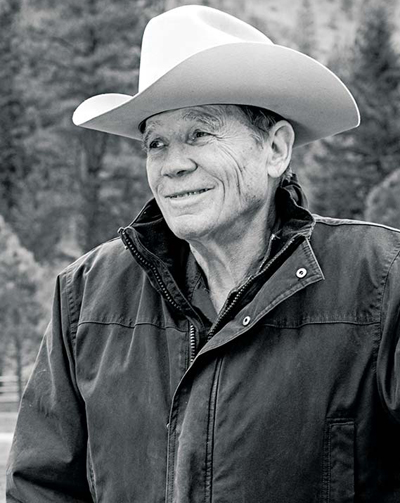

Is it tempting fate to wonder who is the oldest living crime writer? James Lee Burke (below) is now 83, but writing better than ever. A Private Cathedral is another episode in the tempestuous career of Louisiana cop Dave Robicheaux and the force of nature that is is his friend Clete Purcel. Ostensibly about a simmering war between two gangster families, it goes to places untouched by any of the previous twenty two novels.

All the old familiar elements are there – Dave, as ever, battles with drink:

“No, I didn’t want to simply drink. I wanted to swallow pitchers of Jack Daniels and soda and shaved ice and bruised mint, and chase them with frosted mug beer and keep the snakes under control with vodka and Collins mix and cherries and orange slices, until my rockets had a three-day supply of fuel and I was on the far side of the moon.”

Then there are the astonishing and vivid descriptions of the New Iberia landscape, the explosive violence, and Louisiana’s dark history. But this novel has a villain unlike any other James Lee Burke has created before. We have met some pretty evil characters over the years, but they have been human and mortal. Robicheaux, long prone to seeing visions of dead Confederate soldiers, is now faced with an adversary called Gideon, who is also from another world, but with human powers to wreak terrible violence.

The Shondell and the Balangie families manipulate, pervert and use people. Robicheaux suspects that seventeen year-old Isolde Balangie has, to be blunt, been pimped out by her father to Mark Shondell. A ‘friendly fire’ casualty is a talented young singer, Johnny Shondell, Mark’s nephew. Ever present, bubbling away beneath the surface of the Bayou Teche is the past. At one point, we even get to walk past the great man’s house, so why not use his most celebrated quote?

The Shondell and the Balangie families manipulate, pervert and use people. Robicheaux suspects that seventeen year-old Isolde Balangie has, to be blunt, been pimped out by her father to Mark Shondell. A ‘friendly fire’ casualty is a talented young singer, Johnny Shondell, Mark’s nephew. Ever present, bubbling away beneath the surface of the Bayou Teche is the past. At one point, we even get to walk past the great man’s house, so why not use his most celebrated quote?

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

William Faulkner, Requiem For A Nun

The past involves Mafia hits, grievances nursed and festering over generations, and the sense that the Louisiana shoreline has been witness to countless abuses over the years, from the brutality of slavery through to the rape of nature to which abandoned and rotting stumps of oil rigs bear vivid testimony.

Music – usually sad or poignantly optimistic – is always ringing in our ears in the Robicheaux books. Sometimes it is Dixieland jazz, sometimes blues and sometimes the bitter sweet bounce of Cajun songs. At one point, the young singer Johnny takes his guitar and plays:

“He sat down on the bench and made an E chord and rippled the plectrum across the strings. The he sang ‘Born to Be with You’ by the Chordettes. The driving rhythm of the music and the content of the lyrics were like a wind sweeping across a sandy beach.”

In A Private Cathedral, the plot is not over-complex. It is Dave and Clete – The Bobbsy Twins – against the forces of darkness. Burke gives us what is necessary to ensure the narrative drive, but everything is consumed by the poetry. Sometimes it is the poetry of violence and passion; more tellingly, it is the poetry of valiant despair, the light of decency and honour, guttering out in the teeth of a malignant gale which forces Dave and Clete to bend and stumble, but never quite crack and fall.

A Private Cathedral is published by Orion and is out now. For more on James Lee Burke and Dave Robicheaux, click here.

ccasionally I miss out on ARCs and book proofs, and so when I realised the magisterial James Lee Burke had written another Dave Robicheaux novel, and that I was not on the publicist’s mailing list, I went and bought a Kindle version. Just shy of ten quid, but never has a tenner been better spent.

ccasionally I miss out on ARCs and book proofs, and so when I realised the magisterial James Lee Burke had written another Dave Robicheaux novel, and that I was not on the publicist’s mailing list, I went and bought a Kindle version. Just shy of ten quid, but never has a tenner been better spent. To be blunt, JLB is getting on a bit, and one wonders how long he can carry on writing such brilliant books. In the last few novels featuring the ageing New Iberia cop, there has been a definite autumnal feel, and The New Iberia Blues is no exception. Like his creator, Dave Robicheaux is not a young man, but boy, is he ever raging against the dying of the light.

To be blunt, JLB is getting on a bit, and one wonders how long he can carry on writing such brilliant books. In the last few novels featuring the ageing New Iberia cop, there has been a definite autumnal feel, and The New Iberia Blues is no exception. Like his creator, Dave Robicheaux is not a young man, but boy, is he ever raging against the dying of the light. series of apparently ritualised killings baffles the police department, beginning with a young woman strapped to a wooden cross and set adrift in the ocean. This death is just the beginning, and Robicheaux – aided, inevitably, by the elemental force that is Cletus Purcel – struggles to find the killer as the manner of the subsequent deaths exceeds abbatoir levels of brutality. There is no shortage of suspects. A driven movie director deeply in hock to criminal backers, a preening and narcissistic former mercenary, a religious crazy man on the run from Death Row – you pays your money and you takes your choice. We even have the return of the bizarre and deranged contract killer known as Smiley – surely one of the most sinister and damaged killers in all crime fiction. Smiley is described as looking like a shapeless white caterpillar. Horrifically abused as a child, he is happiest when buying ice-creams for children – or killing bad people with Dranol or incinerating them with a flame thrower. Even Robicheaux’s new police partner, the fragrantly named Bailey Ribbons is not beyond suspicion.

series of apparently ritualised killings baffles the police department, beginning with a young woman strapped to a wooden cross and set adrift in the ocean. This death is just the beginning, and Robicheaux – aided, inevitably, by the elemental force that is Cletus Purcel – struggles to find the killer as the manner of the subsequent deaths exceeds abbatoir levels of brutality. There is no shortage of suspects. A driven movie director deeply in hock to criminal backers, a preening and narcissistic former mercenary, a religious crazy man on the run from Death Row – you pays your money and you takes your choice. We even have the return of the bizarre and deranged contract killer known as Smiley – surely one of the most sinister and damaged killers in all crime fiction. Smiley is described as looking like a shapeless white caterpillar. Horrifically abused as a child, he is happiest when buying ice-creams for children – or killing bad people with Dranol or incinerating them with a flame thrower. Even Robicheaux’s new police partner, the fragrantly named Bailey Ribbons is not beyond suspicion.

ith writing that is as potent and smoulderingly memorable as Burke’s, the plot is almost irrelevant, but in between heartbreakingly beautiful descriptions of the dawn rising over Bayou Teche, visceral anger at the damage the oil industry has done to a once-idyllic coast, and jaw-dropping portraits of evil men, Robicheaux patiently and doggedly pursues the killer, and we have a blinding finale which takes The Bobbsey Twins back to their intensely terrified – and terrifying – encounters in the jungles of Indo China.

ith writing that is as potent and smoulderingly memorable as Burke’s, the plot is almost irrelevant, but in between heartbreakingly beautiful descriptions of the dawn rising over Bayou Teche, visceral anger at the damage the oil industry has done to a once-idyllic coast, and jaw-dropping portraits of evil men, Robicheaux patiently and doggedly pursues the killer, and we have a blinding finale which takes The Bobbsey Twins back to their intensely terrified – and terrifying – encounters in the jungles of Indo China.

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands.

he racial element in South-set crime fiction over the last half century is peculiar in the sense that there have been few, if any, memorable black villains. There are plenty of bad black people in Walter Mosley’s novels, but then most of the characters in them are black, and they are not set in what are, for the purposes of this feature, our southern heartlands. Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend.

Black characters are almost always good cops or PIs themselves, like Virgil Tibbs in John Ball’s In The Heat of The Night (1965), or they are victims of white oppression. In the latter case there is often a white person, educated and liberal in outlook, (prototype Atticus Finch, obviously) who will go to war on their behalf. Sometimes the black character is on the side of the good guys, but intimidating enough not to need help from their white associate. John Connolly’s Charlie Parker books are mostly set in the northern states, but Parker’s dangerous black buddy Louis is at his devastating best in The White Road (2002) where Parker, Louis and Angel are in South Carolina working on the case of a young black man accused of raping and killing his white girlfriend. hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

hosts, either imagined or real, are never far from Charlie Parker, but another fictional cop has more than his fair share of phantoms. James Lee Burke’s Dave Robicheaux frequently goes out to bat for black people in and around New Iberia, Louisiana. Robicheaux’s ghosts are, even when he is sober, usually that of Confederate soldiers who haunt his neighbourhood swamps and bayous. I find this an interesting slant because where John Connolly’s Louis will wreak havoc on a person who happens to have the temerity to sport a Confederate pennant on his car aerial, Robicheaux’s relationship with his CSA spectres is much more subtle.

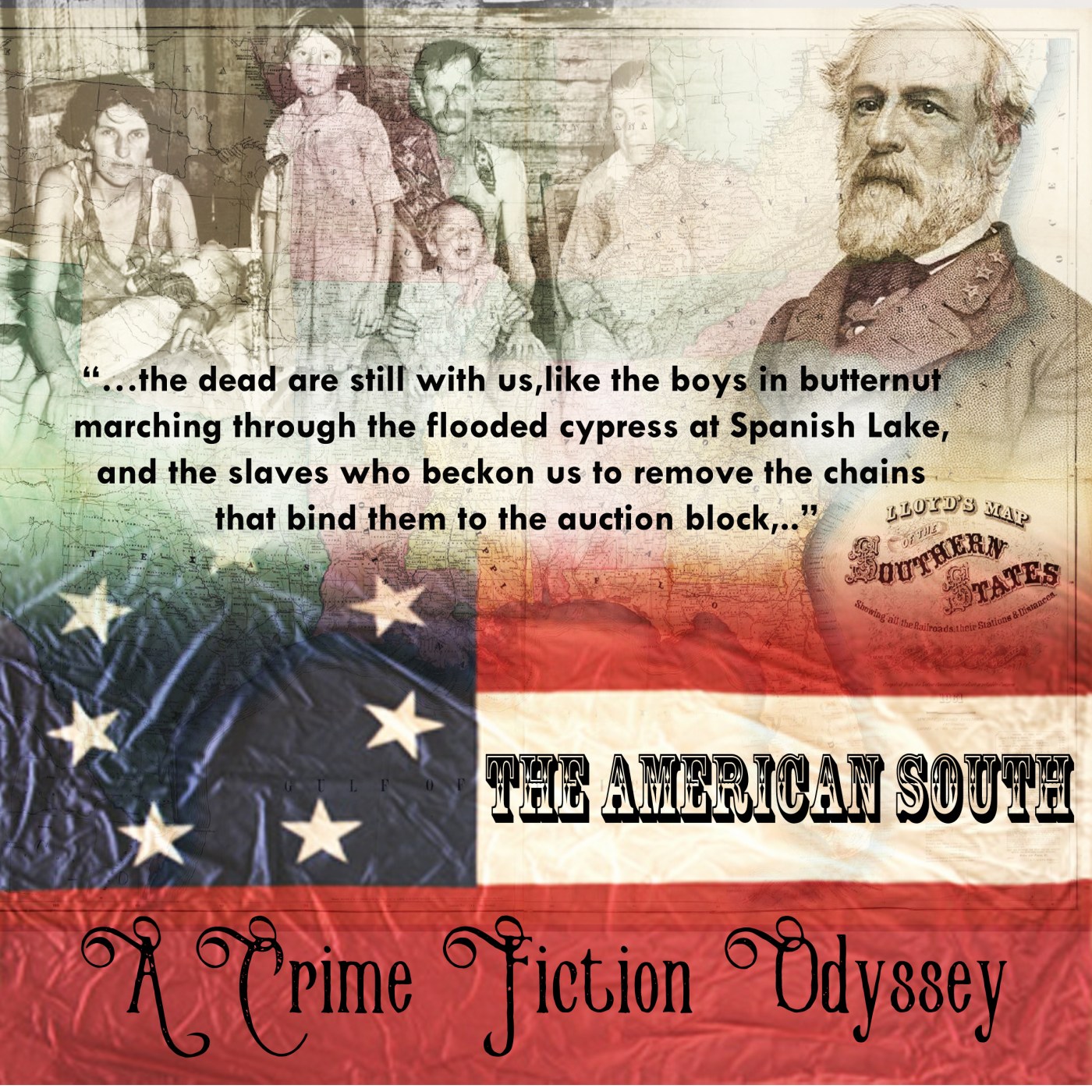

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes:

urke’s Louisiana is both intensely poetic and deeply political. In Robicheaux: You Know My Name he writes: Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

Elsewhere his rage at his own government’s insipid reaction to the devastation of Hurricane Katrina rivals his fury at generations of white people who have bled the life and soul out of the black and Creole population of the Louisian/Texas coastal regions. Sometimes the music he hears is literal, like in Jolie Blon’s Bounce (2002), but at other times it is sombre requiem that only he can hear:

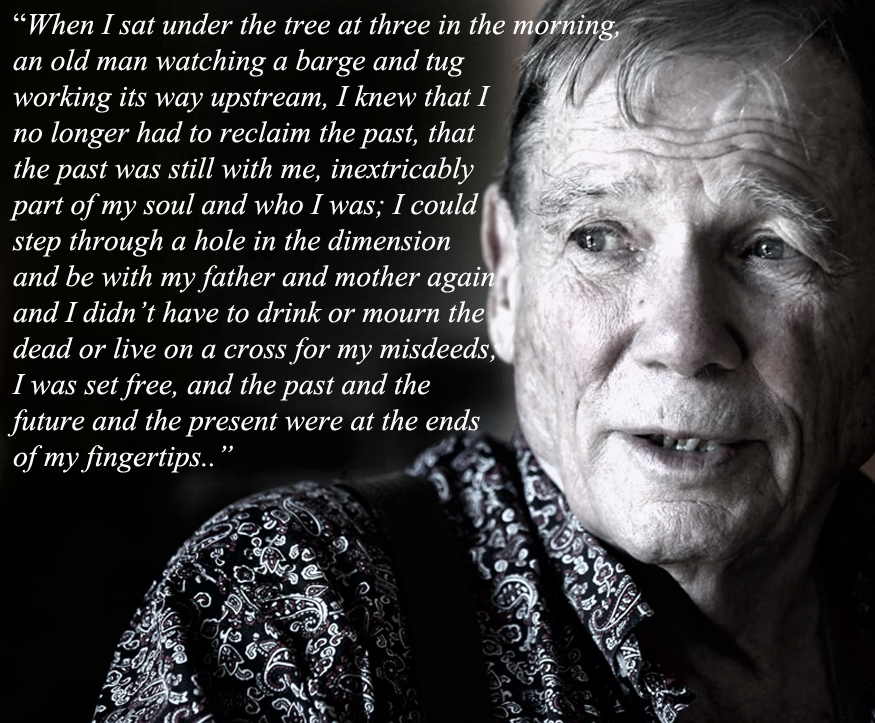

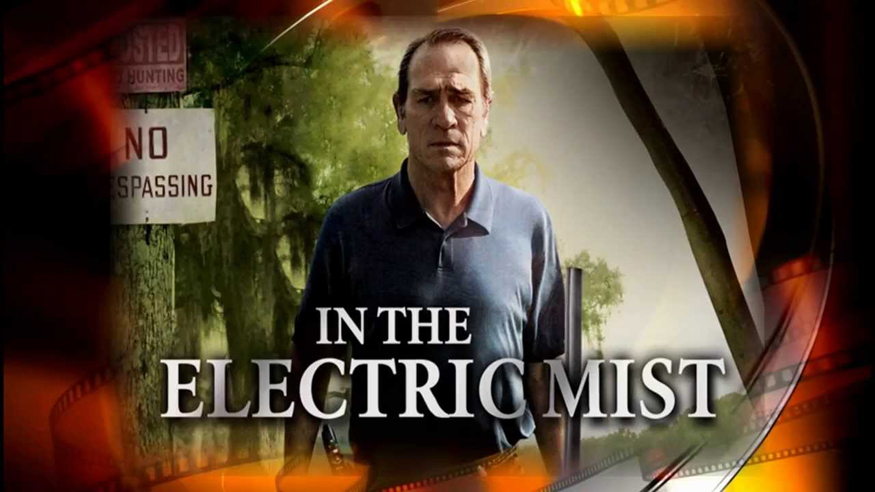

James Lee Burke (left) turned 81 in early December 2017. When I picture the face of his majestic but flawed hero, Dave Robicheaux, it is his creator’s face I see. The Robicheaux books have been filmed several times but the best one I have seen is In The Electric Mist (2009) starring Tommy Lee Jones, and Mr Jones is good a ringer for Mr Burke – and my vision of Robicheaux – as you will ever see.

James Lee Burke (left) turned 81 in early December 2017. When I picture the face of his majestic but flawed hero, Dave Robicheaux, it is his creator’s face I see. The Robicheaux books have been filmed several times but the best one I have seen is In The Electric Mist (2009) starring Tommy Lee Jones, and Mr Jones is good a ringer for Mr Burke – and my vision of Robicheaux – as you will ever see. “That weekend, southern Louisiana was sweltering, thunder cracking as loud as cannons in the night sky; at sunrise, the storm drains clogged with dead beetles that had shells as hard as pecans. It was the kind of weather we associated with hurricanes and tidal surges and winds that ripped tin roofs off houses and bounced them across sugarcane fields like crushed beer cans; it was the kind of weather that gave the lie to the sleepy Southern culture whose normalcy we so fiercely nursed and protected from generation to generation.”

“That weekend, southern Louisiana was sweltering, thunder cracking as loud as cannons in the night sky; at sunrise, the storm drains clogged with dead beetles that had shells as hard as pecans. It was the kind of weather we associated with hurricanes and tidal surges and winds that ripped tin roofs off houses and bounced them across sugarcane fields like crushed beer cans; it was the kind of weather that gave the lie to the sleepy Southern culture whose normalcy we so fiercely nursed and protected from generation to generation.”

HOME by Harlan Coben

HOME by Harlan Coben documentary – it’s a case of murder. Byron (right) reintroduces the characters she created in

documentary – it’s a case of murder. Byron (right) reintroduces the characters she created in