E S Thomson delivers a tale of Gothick horror, which features a young medical apothecary trying to find who killed the senior physician at a gloomy and grotesque hospital for the mentally ill in Victorian London. Jem Flockhart is not what he seems, however. Mr Flockhart is actually a Miss, as he was born female, a surviving twin. For reasons that are not immediately clear, her father switched her with the stillborn brother at birth – a birth which was so traumatic that it killed the mother. Now an adult, helped by her lack of obvious feminine sexual characteristics, she has carved out for herself a persona as a respected medical gentleman and herbalist, a position which, given the prevailing nineteenth century attitude towards women in the medical profession, would have otherwise been unattainable.

Jem, and her companion Will Quartermain – who is unequivocally male – are summoned to view the body of Doctor Rutherford who is found with his ears cut off and stuffed in his mouth, a surgical implement jammed fatally into his brain, and his lips and eyes sewn shut with crudely executed surgical stitches. Amid the carnage, there is no shortage of suspects. The other doctors attached to the asylum are jealous of Rutherford’s eminence, but scathing about his obsession that phrenology – the study of the contours of the skull – is the only true means of understanding mental illness.

As I got further into the book, I was beginning to wonder just what the point was of having Jem Flockhart cross-dressing, as it didn’t seem to have any real bearing on events. Just at the point when I was about to dismiss the idea as a conceit, Thomson delivered a beautifully written scene which made sense of Flockhart’s subterfuge, and added extra poignancy to the relationship between Jem and Will.

As I got further into the book, I was beginning to wonder just what the point was of having Jem Flockhart cross-dressing, as it didn’t seem to have any real bearing on events. Just at the point when I was about to dismiss the idea as a conceit, Thomson delivered a beautifully written scene which made sense of Flockhart’s subterfuge, and added extra poignancy to the relationship between Jem and Will.

We learn that Jem has a disfiguring strawberry birthmark on her face, and Thomson writes with conviction on this issue, as her postscript to the story tells of how she suffered a temporary disfigurement herself, and how she came to be acutely aware of how people looked at her. I can say that this was a gripping read which drew me in to the extent that I finished the book in just a few sessions. The smells, sensations, sounds and social sensitivities of 1850s London are dramatically recreated, and provide much of the novel’s punch. Thomson has an eye for visceral horror and disease that David Cronenberg would approve of, and every time Jem Flockhart takes us into the room of one of the poorer denizens of London, we are inclined to hold our noses and be very careful where we put our feet.

Subtle, the book is not, but it is a dazzling, whirling, swirling riotous melodrama, which leaves little to the imagination. We have, in no particular order, people buried alive, heads being boiled in cauldrons, the shrieking, gibbering and cackling of the insane, a lunatic who keeps cockroaches as pets, the stench and degradation of prison transport ships, club-footed mad-women and the ghastly nineteenth century version of Britain’s Got Talent – the public execution.

Thomson also brings us some larger-than-life characters, none larger than the monstrous Dr Mothersole:

“His face was as smooth as a pebble, his mouth a crimson rosebud between porcelain cheeks. His head had not a single hair upon it and his lashes and brows were entirely absent, giving him a curious appearance, doll-like, and yet half complete….”

Also, very much to her credit, Thomson occasionally has her tongue firmly in her cheek. Why else would the dreadful and bestial Bedlam where most of the action takes place be called Angel Meadow, and what better name for a brothel keeper than Mrs Roseplucker? And what else are we to make of two of the charities patronised by Dr Mothersole, The Truss Society for the Relief of the Ruptured Poor, and The Limbless Costermongers Benevolent Fund ? I loved every page of this book. It is hugely entertaining and, unless something extraordinary happens, will be in the running for one of my books of the year. It is out now, and published by Constable.

A 15 year-old girl, Tania Mills, walks out of her front door and out of the lives of her parents, her family and her friends. She becomes just another statistic. Just another missing person for the police to make a dutiful attempt to appear involved. Just another file, first of all gathering dust on a shelf, and then occupying a tiny space on someone’s hard drive.

A 15 year-old girl, Tania Mills, walks out of her front door and out of the lives of her parents, her family and her friends. She becomes just another statistic. Just another missing person for the police to make a dutiful attempt to appear involved. Just another file, first of all gathering dust on a shelf, and then occupying a tiny space on someone’s hard drive.

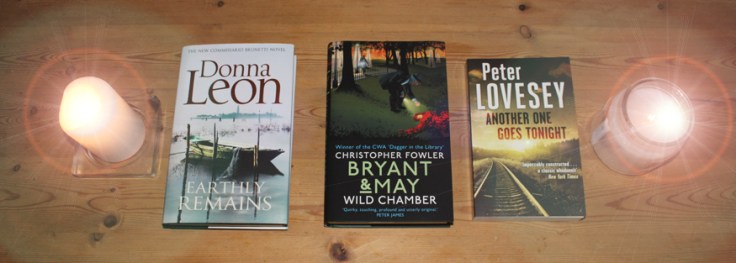

To London, and most elderly pair of investigators currently still working. Existing fans of Arthur Bryant and John May have come to expect quirky humour, clever wordplay, an unrivaled knowledge of the topography and history of London, and a Betjeman-esque poetry of description which sometimes appears humdrum, but is often very profound. Christopher Fowler loves jokes that involve popular culture and brand names, and readers of a certain age will know that even the naming of the two elderly investigators is a little gem of a joke. The cobwebby pair work for the Peculiar Crimes Unit, an esoteric (and purely fictional) branch of the Metropolitan Police. They are constantly under threat of being pensioned off, but their investigations always take them to mysterious parts of London (usually entirely factual). Arthur Bryant – as usual – baffles and exasperates his colleagues, but in this tale his arcane knowledge of London helps the Unit solve the open air version of The Locked Room Mystery. The title? This is from Fowler’s erudite and entertaining website.

To London, and most elderly pair of investigators currently still working. Existing fans of Arthur Bryant and John May have come to expect quirky humour, clever wordplay, an unrivaled knowledge of the topography and history of London, and a Betjeman-esque poetry of description which sometimes appears humdrum, but is often very profound. Christopher Fowler loves jokes that involve popular culture and brand names, and readers of a certain age will know that even the naming of the two elderly investigators is a little gem of a joke. The cobwebby pair work for the Peculiar Crimes Unit, an esoteric (and purely fictional) branch of the Metropolitan Police. They are constantly under threat of being pensioned off, but their investigations always take them to mysterious parts of London (usually entirely factual). Arthur Bryant – as usual – baffles and exasperates his colleagues, but in this tale his arcane knowledge of London helps the Unit solve the open air version of The Locked Room Mystery. The title? This is from Fowler’s erudite and entertaining website.

This week’s award for the most menacing title must go to Peter Lovesey (right) and his Somerset and Avon copper, Peter Diamond. More used to solving high profile murder cases, Diamond is not best pleased when he is called in to investigate an apparent motoring accident. Tragically, a police vehicle, speeding late at night to a possible crime scene, spins off the road, killing one of the officers. Hours later, Diamond discovers that the officer is not the only victim. On an adjacent embankment, undiscovered by the emergency teams, is the rider of a motorised trike. The man is close to death, but Diamond administers CPR successfully enough for the victim to be taken to hospital, where he remains in a critical condition. Diamond, however, is not able to sit back and bask in the warm knowledge that he has carried out a valuable public service. His bosses are desperate that the whole RTA is not blamed on the police force, but what causes Diamond the most anxiety is the emerging likelihood that the man whose life he saved is almost certainly a serial killer.

This week’s award for the most menacing title must go to Peter Lovesey (right) and his Somerset and Avon copper, Peter Diamond. More used to solving high profile murder cases, Diamond is not best pleased when he is called in to investigate an apparent motoring accident. Tragically, a police vehicle, speeding late at night to a possible crime scene, spins off the road, killing one of the officers. Hours later, Diamond discovers that the officer is not the only victim. On an adjacent embankment, undiscovered by the emergency teams, is the rider of a motorised trike. The man is close to death, but Diamond administers CPR successfully enough for the victim to be taken to hospital, where he remains in a critical condition. Diamond, however, is not able to sit back and bask in the warm knowledge that he has carried out a valuable public service. His bosses are desperate that the whole RTA is not blamed on the police force, but what causes Diamond the most anxiety is the emerging likelihood that the man whose life he saved is almost certainly a serial killer.

The random murder of an innocent man? Not exactly. Mahmud Irani was part of a gang of men who groomed, raped and abused a number of white teenage girls. He served a jail term which many believe was too short, considering his crimes.

The random murder of an innocent man? Not exactly. Mahmud Irani was part of a gang of men who groomed, raped and abused a number of white teenage girls. He served a jail term which many believe was too short, considering his crimes.

Jill Dando was an elegant woman, a typical English Rose with more than a little of the Princess Diana about her. As on-screen partner to Nick Ross in BBC’s Crimewatch, she had become one of the best known faces in living rooms across the country. Dando had spent the night with her fiancee in Chiswick, West London, but as she turned the key to enter her own house in nearby Gowan Avenue, Fulham (right), she was attacked. The investigative journalist Bob Woffinden describes what he believes happened next.

Jill Dando was an elegant woman, a typical English Rose with more than a little of the Princess Diana about her. As on-screen partner to Nick Ross in BBC’s Crimewatch, she had become one of the best known faces in living rooms across the country. Dando had spent the night with her fiancee in Chiswick, West London, but as she turned the key to enter her own house in nearby Gowan Avenue, Fulham (right), she was attacked. The investigative journalist Bob Woffinden describes what he believes happened next. In a move which seems more bizarre as every day passes, police arrested a man named Barry George (left) for the killing. George had extensive mental problems, was a fantasist, and had form as being a total indaquate who was obsessed with celebrities. He was convicted of Jill Dando’s muder on 2nd July 2001 but, beyond the jury at his trial, and a few desperate police officers, no-one really believed that he was the killer. After a retrial, he was acquitted of the killing in August 2008. To say he was a loser is misleading, because since his acquittal he has won substantial damages from various newspapers and media outlets. How much of this money has been retained by the wronged man is uncertain: what is more likely is that opportunist lawyers and publicists have trousered much of the loot as a reward for their services.

In a move which seems more bizarre as every day passes, police arrested a man named Barry George (left) for the killing. George had extensive mental problems, was a fantasist, and had form as being a total indaquate who was obsessed with celebrities. He was convicted of Jill Dando’s muder on 2nd July 2001 but, beyond the jury at his trial, and a few desperate police officers, no-one really believed that he was the killer. After a retrial, he was acquitted of the killing in August 2008. To say he was a loser is misleading, because since his acquittal he has won substantial damages from various newspapers and media outlets. How much of this money has been retained by the wronged man is uncertain: what is more likely is that opportunist lawyers and publicists have trousered much of the loot as a reward for their services.

With a father, Leif Gustav Willy Persson a Swedish criminologist and novelist who was a professor in criminology at the Swedish National Police Board, it is hardly surprising that

With a father, Leif Gustav Willy Persson a Swedish criminologist and novelist who was a professor in criminology at the Swedish National Police Board, it is hardly surprising that

Barbara Nadel (right) is best known for her long running and highly successful crime series set in Istanbul, featuring the established cast of Çetin İkmen, a chain-smoking and hard-drinking detective on the Istanbul police force, and his colleagues Mehmet Süleyman, Balthazar Cohen and Armenian pathologist Arto Sarkissian.

Barbara Nadel (right) is best known for her long running and highly successful crime series set in Istanbul, featuring the established cast of Çetin İkmen, a chain-smoking and hard-drinking detective on the Istanbul police force, and his colleagues Mehmet Süleyman, Balthazar Cohen and Armenian pathologist Arto Sarkissian.

Falling Creatures by Katherine Stansfield will appeal to those who like a good period drama, a dead body or two, an atmospheric setting and a sense of Gothic looming over everything. 1844? Tick. Beautiful girl found with throat cut? Tick. Bodmin Moor, beloved of Arthur Conan Doyle and Daphne du Maurier? Tick. Mists, marshes and malevolent men? Tick. The author grew up on Bodmin Moor, and her debut novel The Visitor, won the Holyer an Gof Fiction Prize in 2014. You can find out more about the author (pictured left) by visiting her website

Falling Creatures by Katherine Stansfield will appeal to those who like a good period drama, a dead body or two, an atmospheric setting and a sense of Gothic looming over everything. 1844? Tick. Beautiful girl found with throat cut? Tick. Bodmin Moor, beloved of Arthur Conan Doyle and Daphne du Maurier? Tick. Mists, marshes and malevolent men? Tick. The author grew up on Bodmin Moor, and her debut novel The Visitor, won the Holyer an Gof Fiction Prize in 2014. You can find out more about the author (pictured left) by visiting her website

But all is not well. Arthur Bryant is physically sound enough, but his encyclopaedic mind is starting to betray him. He is suffering episodes of serious dislocation. He causes havoc in what he thinks is an academic library when he’s actually in the soft furnishings department of British Home Stores. While soaking up the ambiance of a Thames-side crime scene, all he can sense are the sights, sounds and smells of the early 20th century docks. John May and the more sprightly members of the PCU have to keep Arthur virtually under lock and key, for his own protection.

But all is not well. Arthur Bryant is physically sound enough, but his encyclopaedic mind is starting to betray him. He is suffering episodes of serious dislocation. He causes havoc in what he thinks is an academic library when he’s actually in the soft furnishings department of British Home Stores. While soaking up the ambiance of a Thames-side crime scene, all he can sense are the sights, sounds and smells of the early 20th century docks. John May and the more sprightly members of the PCU have to keep Arthur virtually under lock and key, for his own protection.

It’s always fun to come late to an established series that has many established followers, if only to see what all the fuss is about. I had covered Catherine Berlin in writing brief news grabs, but House of Bones was to be my first proper read. There is a wonderfully funereal atmosphere throughout the book. Sometimes this is literal, as at the beginning:

It’s always fun to come late to an established series that has many established followers, if only to see what all the fuss is about. I had covered Catherine Berlin in writing brief news grabs, but House of Bones was to be my first proper read. There is a wonderfully funereal atmosphere throughout the book. Sometimes this is literal, as at the beginning:

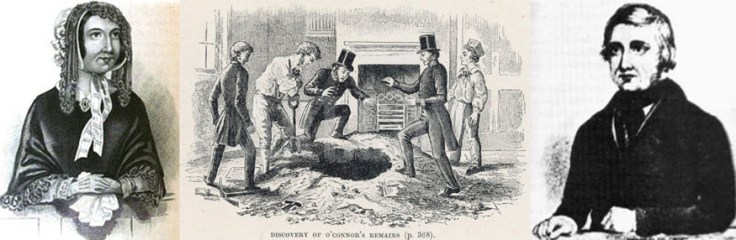

This is the tale of a ghastly pair of opportunists in Victorian London. Frederick Manning turned a blind eye to his wife, Marie, while she dispensed her favours to a rich customs official, Patrick O’Connor. The pair prepared a grave for him under their kitchen floor, and having murdered him, tried to escape with all his money. Inevitably, they were caught, and provided yet another job for William Calcraft, the Lord High Executioner.

This is the tale of a ghastly pair of opportunists in Victorian London. Frederick Manning turned a blind eye to his wife, Marie, while she dispensed her favours to a rich customs official, Patrick O’Connor. The pair prepared a grave for him under their kitchen floor, and having murdered him, tried to escape with all his money. Inevitably, they were caught, and provided yet another job for William Calcraft, the Lord High Executioner.