One of my sons was at Leeds University, and my impression of the city during visits either to move house or to bring food and supplies, was of a place very much sure of itself, embracing the past while relishing a vibrant future. But this was largely Headingly, the university quarter, full of bookshops, trendy cafes and largely peopled by the offspring of comfortable middle class people like me and my wife.

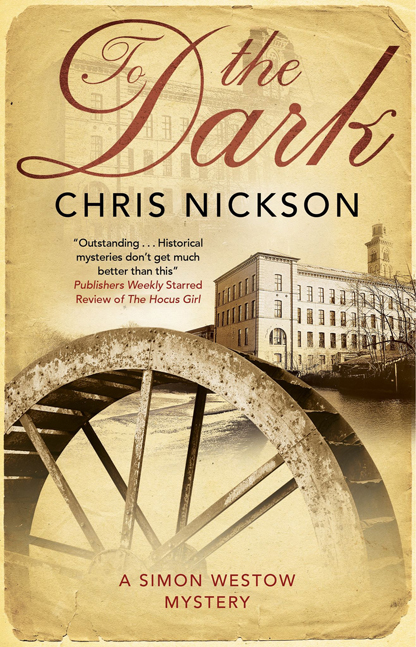

Chris Nickson’s Leeds is a very different place. In the Tom Harper novels (click link) and in this, the latest account of the career of Simon Westow, thief-taker, things are very, very different. This is Georgian England (1823, in this case) and Westow – in an age before a regular police force – earns his living recovering stolen property, for a percentage of its value. He has no judicial authority, save that of his quick wits, his fists and- occasionally – his knife. Recovering from a debilitating illness, Westow is back on the streets, and is juggling with several different investigations. A man has been hauled out of the river. His throat has been fatally slashed, and one of his hands has been hacked off. His brother hires Westow to answer ‘who?’ and ‘why?’.

Chris Nickson’s Leeds is a very different place. In the Tom Harper novels (click link) and in this, the latest account of the career of Simon Westow, thief-taker, things are very, very different. This is Georgian England (1823, in this case) and Westow – in an age before a regular police force – earns his living recovering stolen property, for a percentage of its value. He has no judicial authority, save that of his quick wits, his fists and- occasionally – his knife. Recovering from a debilitating illness, Westow is back on the streets, and is juggling with several different investigations. A man has been hauled out of the river. His throat has been fatally slashed, and one of his hands has been hacked off. His brother hires Westow to answer ‘who?’ and ‘why?’.

A rich and powerful Leeds entrepreneur called Arden sets Westow the task of recovering a pair of valuable candlesticks, stolen from his son. But when the investigation is concluded, all too easily, Westow is forced to wonder if he is not being used as a dupe in some larger scheme. To add to his workload, Westow sets out to avenge the deaths of two lads, apparently starved then beaten to death by brutal overseers at a Leeds factory owned by a mysterious man named Seaton.

Westow’s assistant is a deceptively fragile young woman called Jane. Raped by her father and then thrown out on the street by her mother, she has learned to survive by cunning – and a fatal ability to use a knife, without a second thought, or her dreams being haunted by her victims. She has, to some extent, ‘come in from the cold’ as she no longer lives on the street, but with an elderly lady of infinite kindness.

As Leeds is cut off from the rest of the world by deep snow, there are more deaths, but few answers. The only thing that is clear in Westow’s mind is that there is that – for whatever reason – a blood covenant exists between Arden and Seaton. Two rich and powerful men who have the rudimentary criminal justice system within Leeds at their beck and call. Two men who want ruin – and death – to come to Westow and those he loves.

Before we reach a terrifying finale at a remote farm in the hills beyond Leeds, Nickson demonstrates why he is such a good – and impassioned – novelist. He burns with an anger at the decades of of injustice, hardship and misery inflicted on working people by the men who built industrial Leeds, and made their fortunes on the broken bodies of the poor strugglers who lived such dark lives in the insanitary terraces that clustered around the mills and foundries. In terms of modern politics, Chris Nickson and I are worlds apart and there is, of course, a separate debate to be had about the long term effects of the industrial revolution, but it would be a callous person who could remain unmoved by the accounts of the human wreckage caused by the huge technological upheavals of the 18th and 19th centuries.

There is. of course, a noble tradition of writers who exposed social injustice nearer to their own times – Charles Dickens, Charles Kingsley, Robert Tressell and John Steinbeck, to name but a few, but we shouldn’t dismiss Nickson’s anger because of the distance between his books and the events he describes. As he walks the streets of modern Leeds, he clearly feels every pang of hunger, every indignity, every broken bone and every hopeless dawn experienced by the people whose blood and sweat made the city what it is today. That he can express this while also writing a bloody good crime novel is the reason why he is, in my opinion, one of our finest contemporary writers. The Blood Covenant is published by Severn House and is out now.

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians.

A trip to Scunthorpe might not be too high on many people’s list of literary pilgrimages, but we are calling in for a very good reason, and that is because it was the probable setting for one of the great crime novels, which was turned into a film which regularly appears in the charts of “Best Film Ever”. I am talking about Jack’s Return Home, better known as Get Carter. Hang on, hang on – that was in Newcastle wasn’t it? Yes, the film was, but director Mike Hodges recognised that Newcastle had a more gritty allure in the public’s imagination than the north Lincolnshire steel town, which has long been the butt of gags in the stage routine of stand-up comedians. the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

the river to attend Art college in Hull before moving to London to work as an animator. His novels brought him great success but little happiness, and after his marriage broke up, he moved back to Lincolnshire to live with his mother. By then he was a complete alcoholic and he died of related causes in 1982. His final novel GBH (1980) – which many critics believe to be his finest – is played out in the bleak out-of-season Lincolnshire coastal seaside resorts which Lewis would have known in the sunnier days of his childhood. In case you were wondering about how Jack’s Return Home is viewed in the book world, you can pick up a first edition if you have a spare £900 or so in your back pocket.

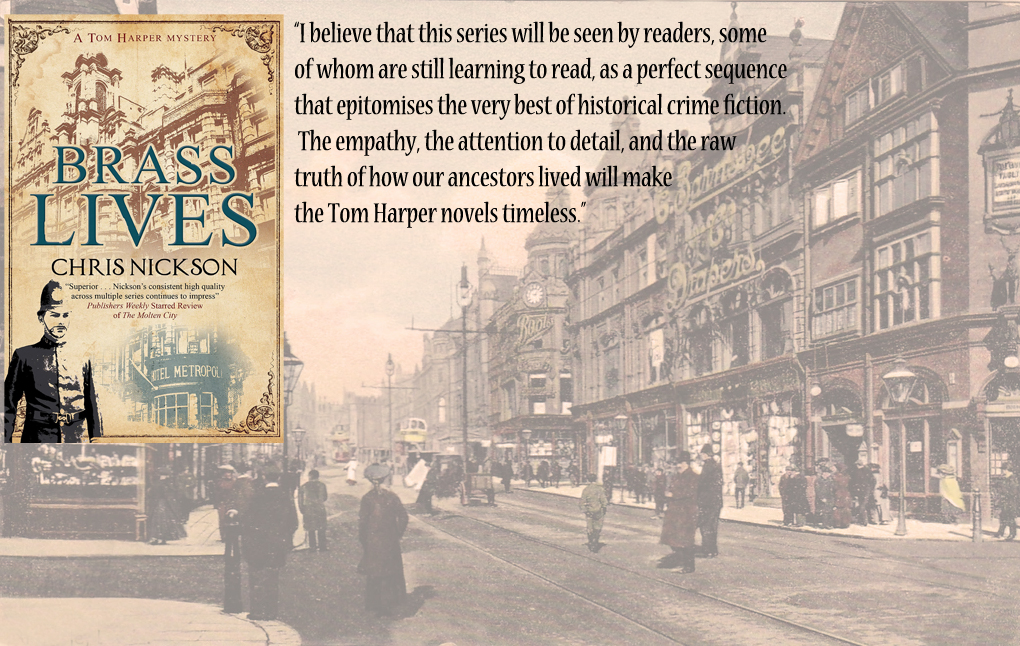

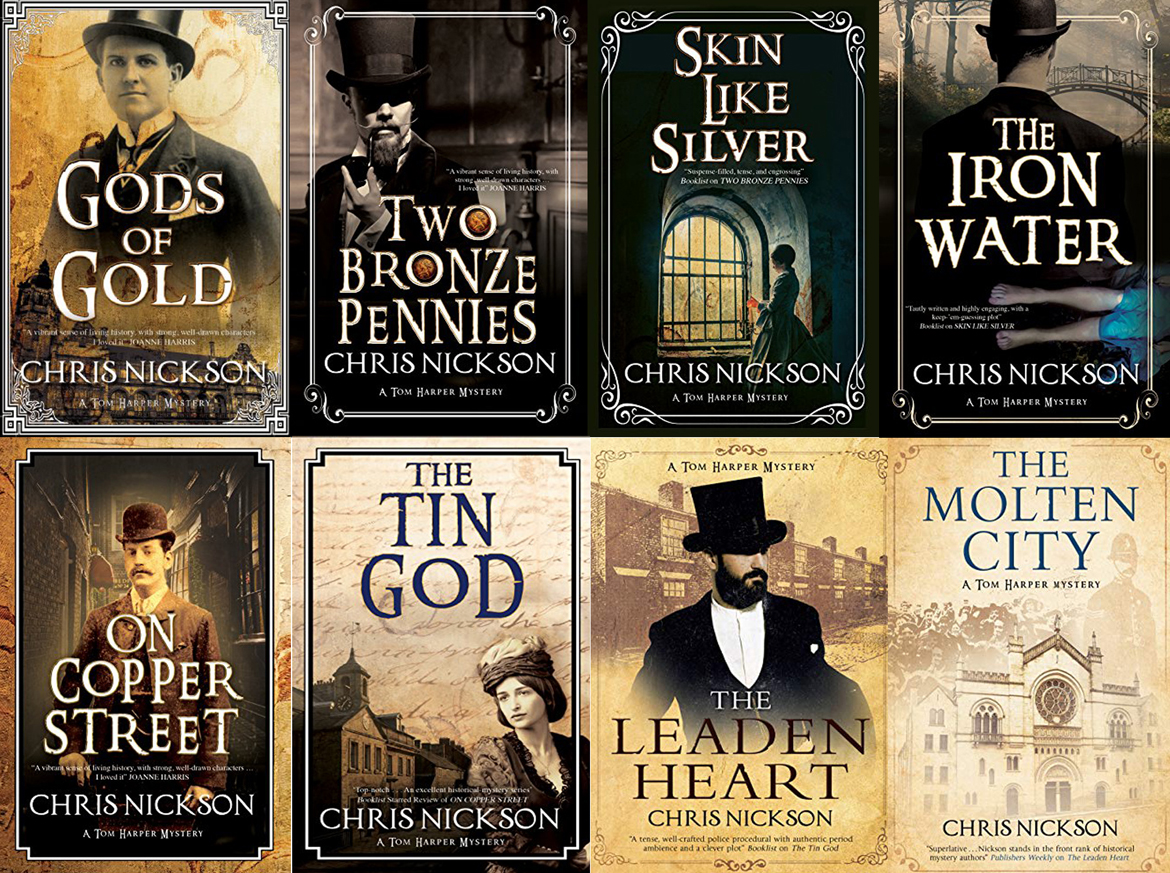

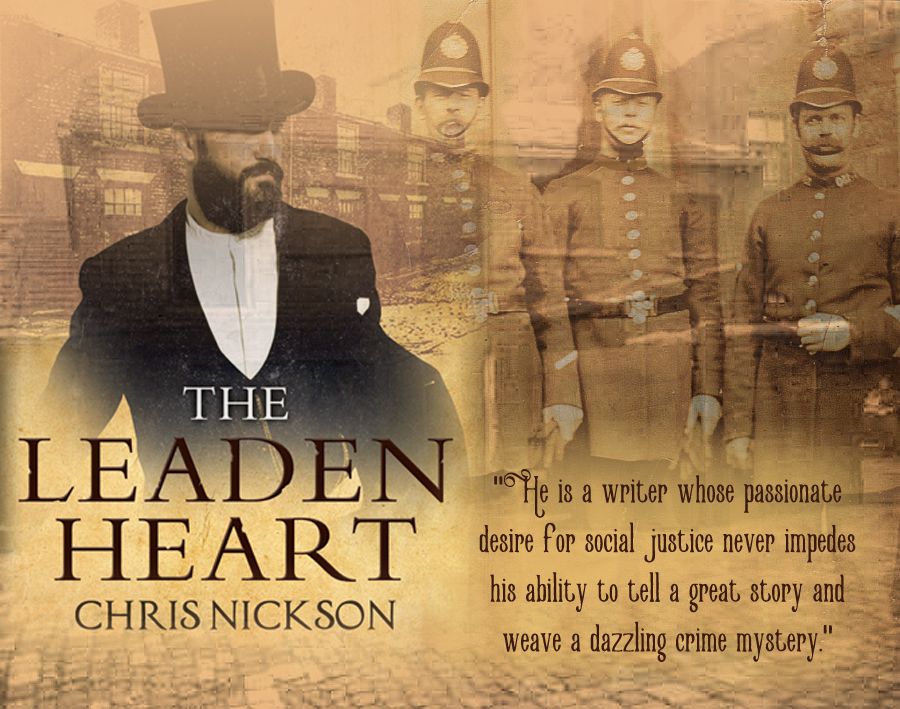

We first met Leeds policeman Tom Harper in Gods of Gold (2014) when he was a young CID officer, and the land was still ruled by Queen Victoria. Now, in The Molten City, Harper is a Superintendent and the Queen is seven years dead. ‘Bertie’ – Edward VII – is King, and England is a different place. Leeds, though, is still a thriving hub of heavy industry, pulsing with the throb of heavy machinery. And it remains grimy, soot blackened and with pockets of degradation and poverty largely ignored by the wealthy middle classes. But there are motor cars on the street, and the police have telephones. Other things are stirring, too. Not all women are content to remain second class citizens, and pressure is being put on politicians to consider giving women the vote. Sometimes this is a peaceful attempt to change things, but other women are prepared to go to greater lengths.

We first met Leeds policeman Tom Harper in Gods of Gold (2014) when he was a young CID officer, and the land was still ruled by Queen Victoria. Now, in The Molten City, Harper is a Superintendent and the Queen is seven years dead. ‘Bertie’ – Edward VII – is King, and England is a different place. Leeds, though, is still a thriving hub of heavy industry, pulsing with the throb of heavy machinery. And it remains grimy, soot blackened and with pockets of degradation and poverty largely ignored by the wealthy middle classes. But there are motor cars on the street, and the police have telephones. Other things are stirring, too. Not all women are content to remain second class citizens, and pressure is being put on politicians to consider giving women the vote. Sometimes this is a peaceful attempt to change things, but other women are prepared to go to greater lengths.

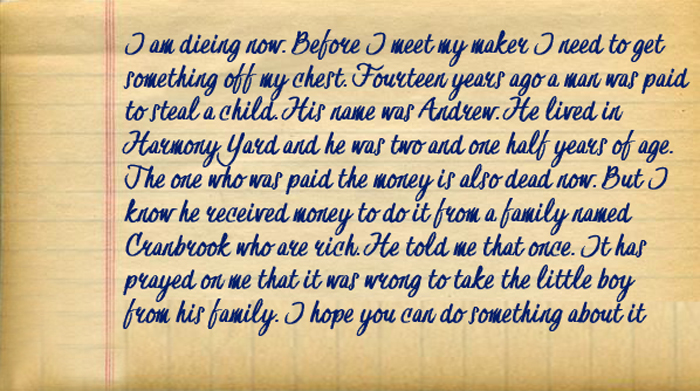

t was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Britain had anything like an organised police force. The Hocus Girl is set well before that time, and even a developing community like Leeds relied largely on local Constables and The Watch – both institutions being badly paid, unsupported and mostly staffed by elderly individuals who would dodder a mile to avoid any form of trouble or confrontation. There were, however, men known as Thieftakers. The title is self-explanatory. They were men who knew how to handle themselves. They were employed privately, and were outside of the rudimentary criminal justice system.

t was not until the middle of the nineteenth century that Britain had anything like an organised police force. The Hocus Girl is set well before that time, and even a developing community like Leeds relied largely on local Constables and The Watch – both institutions being badly paid, unsupported and mostly staffed by elderly individuals who would dodder a mile to avoid any form of trouble or confrontation. There were, however, men known as Thieftakers. The title is self-explanatory. They were men who knew how to handle themselves. They were employed privately, and were outside of the rudimentary criminal justice system. Such a man is Simon Westow. He is paid, cash in hand, to recover stolen goods, by whatever means necessary. His home town of Leeds is changing at an alarming rate as mechanised cloth mills replace the cottage weavers, and send smoke belching into the sky and chemicals into the rivers. We first met Westow in The Hanging Psalm, and there we were also introduced to young woman called Jane. She is a reject, a loner, and she is also prone to what we now call self-harm. She is a girl of the streets, but not in a sexual way; she knows every nook, cranny, and ginnel of the city; as she shrugs herself into her shawl, she can become invisible and anonymous. Her sixth sense for recognising danger and her capacity for violence – usually via a wickedly honed knife – makes her an invaluable ally to Westow. I have spent many enjoyable hours reading the author’s books, and it is my view that Jane is the darkest and most complex character he has created. In many ways The Hocus Girl is all about her.

Such a man is Simon Westow. He is paid, cash in hand, to recover stolen goods, by whatever means necessary. His home town of Leeds is changing at an alarming rate as mechanised cloth mills replace the cottage weavers, and send smoke belching into the sky and chemicals into the rivers. We first met Westow in The Hanging Psalm, and there we were also introduced to young woman called Jane. She is a reject, a loner, and she is also prone to what we now call self-harm. She is a girl of the streets, but not in a sexual way; she knows every nook, cranny, and ginnel of the city; as she shrugs herself into her shawl, she can become invisible and anonymous. Her sixth sense for recognising danger and her capacity for violence – usually via a wickedly honed knife – makes her an invaluable ally to Westow. I have spent many enjoyable hours reading the author’s books, and it is my view that Jane is the darkest and most complex character he has created. In many ways The Hocus Girl is all about her. he 1820s were a time of great domestic upheaval in Britain. The industrial revolution was in its infancy but was already turning society on its head. The establishment was wary of challenge, and when Davey Ashton, a Leeds man with revolutionary ideas is arrested, Simon Westow – a long time friend – comes to his aid. As Ashton languishes in the filthy cell beneath Leeds Moot Hall, Westow discovers that he is treading new ground – political conspiracy and the work of an agent provocateur.

he 1820s were a time of great domestic upheaval in Britain. The industrial revolution was in its infancy but was already turning society on its head. The establishment was wary of challenge, and when Davey Ashton, a Leeds man with revolutionary ideas is arrested, Simon Westow – a long time friend – comes to his aid. As Ashton languishes in the filthy cell beneath Leeds Moot Hall, Westow discovers that he is treading new ground – political conspiracy and the work of an agent provocateur.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Nickson’s latest book introduces a new character, Simon Westow, who walks familiar streets – those of Leeds – but our man is living in Georgian times. England in 1820 was a kingdom of uncertainty. Poor, mad King George was dead, succeeded by his fat and feckless son, the fourth George. Veterans of the war against Napoleon, like many others in later years, found that their homeland was not a land fit for heroes. The Cato Street conspirators, having failed to assassinate the Cabinet, were executed.

Nickson’s latest book introduces a new character, Simon Westow, who walks familiar streets – those of Leeds – but our man is living in Georgian times. England in 1820 was a kingdom of uncertainty. Poor, mad King George was dead, succeeded by his fat and feckless son, the fourth George. Veterans of the war against Napoleon, like many others in later years, found that their homeland was not a land fit for heroes. The Cato Street conspirators, having failed to assassinate the Cabinet, were executed.

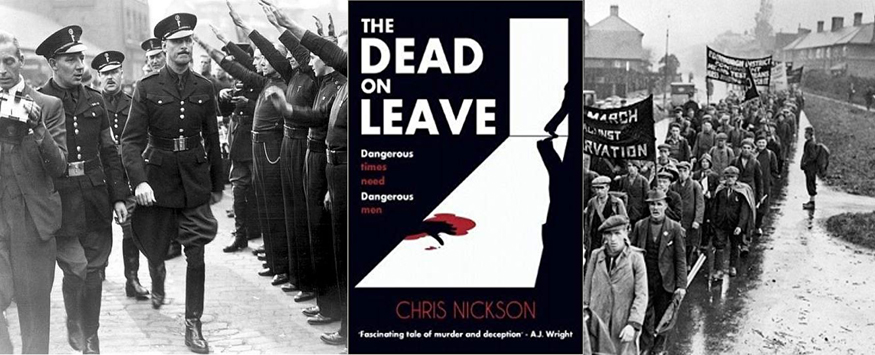

It appears the dead man is a would-be follower of Sir Oswald Mosley, charismatic leader of the British Union of Fascists and, after an appearance in Leeds by Mosley and his Blackshirts turns into a riot, it is tempting for the police to think that the murder is politically inspired. As Raven tries to make sense of the killing, he has his own demons to face. Like many other Yorkshiremen, Raven is a Great War veteran, even though his war was brief and horrific. Only able to see active service in the dog-days of the conflict, he was unlucky enough to be close to a fuel dump which was hit by a stray shell. There’s a line from a song about that war, which goes,

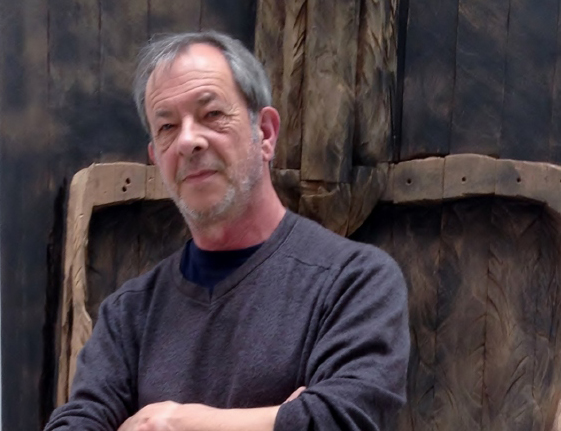

It appears the dead man is a would-be follower of Sir Oswald Mosley, charismatic leader of the British Union of Fascists and, after an appearance in Leeds by Mosley and his Blackshirts turns into a riot, it is tempting for the police to think that the murder is politically inspired. As Raven tries to make sense of the killing, he has his own demons to face. Like many other Yorkshiremen, Raven is a Great War veteran, even though his war was brief and horrific. Only able to see active service in the dog-days of the conflict, he was unlucky enough to be close to a fuel dump which was hit by a stray shell. There’s a line from a song about that war, which goes, The Dead On Leave is very bleak in places. Hope is in short supply among the working people in Leeds, and men have no qualms about building a wooden platform for Moseley to rant from, because a job is a job; consciences are a luxury way beyond the reach of folk whose families have empty bellies. Nickson (right) is a writer, with social justice at the front of his mind and he wears his heart on his sleeve. I doubt that he and I agree on much in today’s political world, but I can think of no modern British author who writes with such passion and fluency about historical social issues.

The Dead On Leave is very bleak in places. Hope is in short supply among the working people in Leeds, and men have no qualms about building a wooden platform for Moseley to rant from, because a job is a job; consciences are a luxury way beyond the reach of folk whose families have empty bellies. Nickson (right) is a writer, with social justice at the front of his mind and he wears his heart on his sleeve. I doubt that he and I agree on much in today’s political world, but I can think of no modern British author who writes with such passion and fluency about historical social issues.