Swadling Street in Leamington is an unassuming thoroughfare, with houses which were built on the old Shrubland Estate between the wars. It was named after a Leamington councillor of the 1920s, and in 1931 it boasted twenty addresses. In January 1949, number 6 was occupied by Edward Sullivan. A 49 year-old Irishman and father of six children – three sons and three daughters – he worked as a builder’s labourer. Known to his mates – inevitably – as Paddy – he was working on a council house building project on Westlea Road, which was another between-wars development on what had been the Shrubland Estate.

Swadling Street in Leamington is an unassuming thoroughfare, with houses which were built on the old Shrubland Estate between the wars. It was named after a Leamington councillor of the 1920s, and in 1931 it boasted twenty addresses. In January 1949, number 6 was occupied by Edward Sullivan. A 49 year-old Irishman and father of six children – three sons and three daughters – he worked as a builder’s labourer. Known to his mates – inevitably – as Paddy – he was working on a council house building project on Westlea Road, which was another between-wars development on what had been the Shrubland Estate.

Just a couple of hundred yards away was Bury Road – again, named after a local civic dignitary – and number 120 was the home of Gordon Towle. He was 19 years old, and lived with his wife Lilian, who he had married just three months earlier. He worked on the same building site as Edward Sullivan. Towle was a Leamington lad, and had earlier applied to join the army, but had been rejected on medical grounds. At the age of 10, he had damaged his head in an accident, and went to hospital to have the wound dressed, but was sent home again during what he remembered as “the bad raids”. There were three air raids on Leamington on 1940. The first, in August, resulted in no casualties, but as a result of subsequent raids in October and November, 7 people were killed. It seems that Towle’s mother had a history of mental illness, and had been taken in care, which resulted in Towle and his two brothers being sent to live with family friends in Rugby.

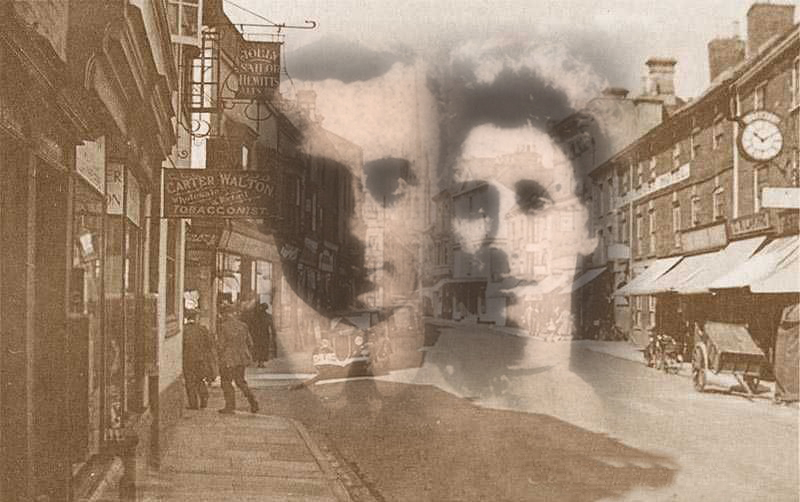

It’s worth, at this point, to digress slightly and look at what Leamington was like in 1949. The great diaspora of families from the teeming terraces south of High Street up to the new builds in Lillington had yet to happen. Names of WW2 casualties had been added to the town war memorial but, thankfully, not in the number that the stonemasons had been tasked with in 1919. The damage caused by the Luftwaffe bombs in an effort to target Lockheed and Flavels factories had been cleared away and, despite the huge swing away from the Conservative party in the 1945 general election, Leamington still had faith in its pre-war MP, Anthony Eden. I was just 18 months old in 1949, so my memories are totally unreliable but I can tell you that our house in Victoria Street still had gas lighting, a pump in the scullery, and a large ‘copper’ in which water was heated for the weekly bath.

So, back to Edward Sullivan and Gordon Towle. The two men had clearly rubbed each other up the wrong way. Sullivan had mocked Towle for his lack of military service. We know that Sullivan had a son in the British army, and he himself had been a regular soldier with the Royal Army Service Corps during The Great War. He stayed in the army after the Armistice and did a further four years service out in India, returning in 1923. People tend to forget that men from what was to become the Republic of Ireland played a gallant part in The Great War. There were also some who fought for the British in WW2, and they were treated in a shocking manner by the Irish state after the war.

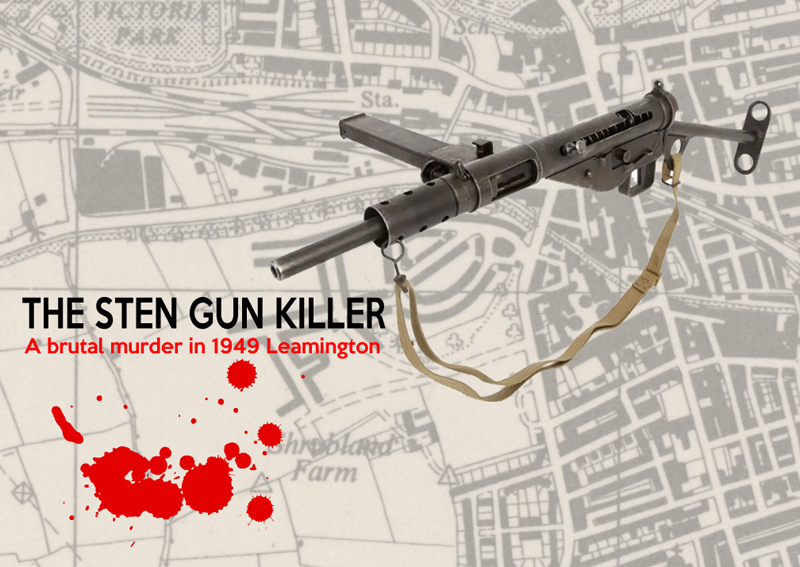

Whatever the reasons for the animosity between Sullivan and Towle, things were about to come to a dramatic and bloody head. Heaven only knows how or why, but Gordon Towle had, secreted in his bedroom a Sten gun and hundred rounds of ammunition. Most lads growing up in the 1950s with access to Commando comics and other bloodthirsty stuff, will have an instant image of what a Sten gun looks like. It was a brutally simple piece of engineering – a sub machine gun designed for destruction rather than accuracy. A full magazine contained 32 rounds of 9mm bullets, and at short range it was a devastating weapon. In part two, we will discover how and why Gordon Towle had a Sten gun in his possession and – more importantly – what he did with it.

PART TWO will go live on Thursday 1st April

Dublin copper DI Tom Reynolds is summoned from the dubious delights of his family Christmas to solve a murder. Readers of the previous three Tom Reynolds books might think there is little remarkable about that, but this time the corpse has been in the ground for rather longer than usual. Forty years, in fact. On the island of Oileán na Caillte, the pathologists have been disinterring corpses from a mass grave of the unfortunates who passed away as patients of the long-defunct psychiatric institution, St Christina’s. Those involved in the grim task discover nothing illegal, as all the residents of the burial pit were laid to rest in body bags, tagged and entered onto the hospital records. With one exception. That exception is the corpse of one of St Christina’s medical staff Dr Conrad Howe, who mysteriously disappeared forty Christmases ago. No body bag or tag for Dr Howe, but a rather surreptitious last resting place wedged between two other corpses.

Dublin copper DI Tom Reynolds is summoned from the dubious delights of his family Christmas to solve a murder. Readers of the previous three Tom Reynolds books might think there is little remarkable about that, but this time the corpse has been in the ground for rather longer than usual. Forty years, in fact. On the island of Oileán na Caillte, the pathologists have been disinterring corpses from a mass grave of the unfortunates who passed away as patients of the long-defunct psychiatric institution, St Christina’s. Those involved in the grim task discover nothing illegal, as all the residents of the burial pit were laid to rest in body bags, tagged and entered onto the hospital records. With one exception. That exception is the corpse of one of St Christina’s medical staff Dr Conrad Howe, who mysteriously disappeared forty Christmases ago. No body bag or tag for Dr Howe, but a rather surreptitious last resting place wedged between two other corpses. Other than that dark angel, the cast of suspects includes another former physician, now himself just days away from death, and others whose culpability in the inhuman treatment of St Christina’s patients has left psychological scars, some of which have become dangerously infected. Of course, this being, among other things, a brilliant whodunnit, Jo Spain (right) allows Tom Reynolds – and us readers – to make one major assumption. She then takes great pleasure, the deviously scheming soul that she is, in waiting until the final few pages before turning that assumption not so much on its head as making it do a bloody great cartwheel.

Other than that dark angel, the cast of suspects includes another former physician, now himself just days away from death, and others whose culpability in the inhuman treatment of St Christina’s patients has left psychological scars, some of which have become dangerously infected. Of course, this being, among other things, a brilliant whodunnit, Jo Spain (right) allows Tom Reynolds – and us readers – to make one major assumption. She then takes great pleasure, the deviously scheming soul that she is, in waiting until the final few pages before turning that assumption not so much on its head as making it do a bloody great cartwheel.