Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

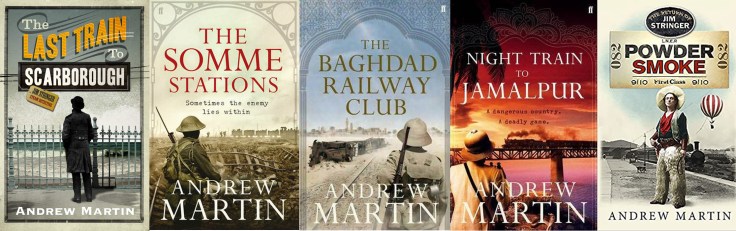

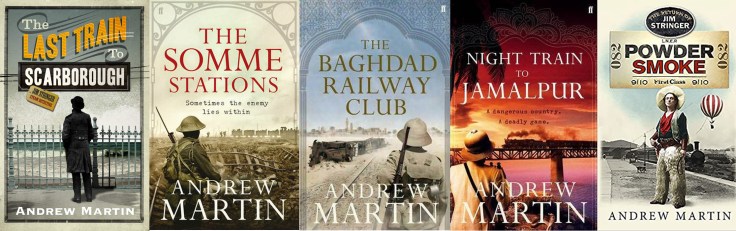

The next four novels see Jim rising steadily through the ranks of railway nobility, but in 1914 the world changes for ever, and Jim, like tens of thousands of other fathers, husbands, brothers and sons, answers the country’s call and joins up to fight the Kaiser, but with his expertise as a railwayman. The Great War, while not as completely global as the conflict that followed just twenty five years later, was not confined to the blood-soaked farmlands of France and Flanders. After solving a front-line murder in The Somme Stations (2011) Jim goes east in The Bagdhad Railway Club (2012) and Night Train To Jamalpur (2013) and emerges some years after the war, more or less unscathed and back home in York, in Powder Smoke (2021)

Andrew Martin is many things – steeped in railway lore from his childhood, Oxford graduate, qualified barrister, performing musician, born in York and writer of novels light years distant from crime fiction. If he were ever to have a tombstone inscription, I do hope he would include (in brackets) “also known as Jim Stringer”. Stringer is a brilliant creation; not a ‘bish-bash-bosh’ hero, for sure, but a man with a well-defined moral compass and a gimlet eye for wrong-doing – be it in railway procedure or life in general.

Although I don’t quite belong to Jim Stringer’s era, when I read his books I am back in my relatively blameless youth (remember when Philip Larkin said sex was invented) and I am on a station platform somewhere in the Midlands, probably showered with soot from a venting steam engine, pen in one hand, notebook in the other, and with a school satchel containing sandwiches and a bottle of pop slung over my shoulder.

We now face a long haul over The Pennines and, just after the ancient town of Skipton, we trade the white rose for the red, and pass into the County Palatine of Lancashire. It is just possible that we might pass within a stone’s throw of a moorland pub called The Tawny Owl. Were we to call in for refreshment we might be serves by a fifty-something chap called Henry Christie. More than likely, though he will be out somewhere between Preston and Blackpool ‘helping police with their inquiries’. In Henry’s case, however, this is not the standard police cliché for being ‘nicked’ but is to be taken absolutely literally, as retired copper Christie has a new role as a consultant to his former colleagues.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants.

Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

What comes as standard in this superb series is tight plotting, total procedural authenticity, some pretty mind blowing violence and brutality but – above all – an intensely human and likeable main character. Click on the images below to read reviews of some of the more recent Henry Christie novels.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

Ever onwards, and ever northward to the ancient city of York. For all that it houses the magnificent medieval minster and has a history going back to the Eboracum of Roman times, fewer people remember that York was also a great railway city, and there can be no more appropriate place to house the National Railway Museum. Like many men now in the autumn of their years I was an enthusiastic trainspotter back in the days of steam, so it is – I hope – perfectly understandable that I have chosen the Jim Stringer novels by Andrew Martin for this stop on our trip. Martin introduced Stringer in The Necropolis Railway (2002) when Stringer is very much at the bottom of the railway hierarchy, and working in London, but by 2004 in The Blackpool Highflyer, Stringer has married his landlord’s daughter – the beautiful Lydia – and has been promoted to a job in York.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants.

His creator, Nick Oldham, knows of what he writes, as he is a former police officer, and the 29th book in this long running and successful series is due out at the end of November. So, what can readers expect from a Henry Christie story? It depends where you start, of course, because if you go back to the beginning in 1996, Peter Shilton was still in goal, but for Leyton Orient, England lost to Germany (on penalties, naturally) in the Euros semi-final, the trial of men accused of murdering Stephen Lawrence collapsed and John Major was in his second term as British Prime Minister. In A Time For Justice Christie is a relatively junior Detective Inspector – and someone who is seriously out of favour with his bosses, and has to tackle a cocky mafia hitman who thinks the English police are a joke. As the novels progress over the years, Christie rises through the ranks, but he is still someone who is viewed with some suspicion by the few officers who outrank him – the chief constables and their assistants. Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

Henry Christie is always hands on, and he has the scars – mostly physical, but one or two mental lesions – to prove it. His personal life has been a mixture of love, passion, tragedy and disappointment. His geographical battle grounds are usually confined to the triangle formed of Preston, Lancaster and Blackpool. This is an area that Oldham (right) himself knows very well, of course, thanks to his years as a copper, but it is also very cleverly chosen, because it allows the author to play with very different human and geographical landscapes. The brooding moorland to the east is a wonderful setting for all kinds of wrong-doing, while the seaside town of Blackpool, despite the golden sands, donkey rides, candy floss and cheerful seaside ambience, houses one of the worst areas of deprivation in the whole country, with run-down and lawless former council estates controlled by loan sharks, traffickers and criminal families of the worst sort.

We are left to imagine what he looks like. He never uses violence as a matter of habit, but his inner rage fuels a temper which can destroy those who are unwise enough to provoke him. Why is he so bitter, so angry, so disgusted? Of himself, he says:

We are left to imagine what he looks like. He never uses violence as a matter of habit, but his inner rage fuels a temper which can destroy those who are unwise enough to provoke him. Why is he so bitter, so angry, so disgusted? Of himself, he says:

Investigating duos are always a reliable way to spin a police novel, and in this case we have Inspector Harvey Marmion and Sergeant Joe Keedy of the Metropolitan Police. Marmion is married to Ellen, with a son and daughter. Son Paul has been mentally damaged by his time on the Western Front, and has now disappeared leaving no clue as to his whereabouts, while daughter Alice – also a service police officer – is engaged to Keedy.

Investigating duos are always a reliable way to spin a police novel, and in this case we have Inspector Harvey Marmion and Sergeant Joe Keedy of the Metropolitan Police. Marmion is married to Ellen, with a son and daughter. Son Paul has been mentally damaged by his time on the Western Front, and has now disappeared leaving no clue as to his whereabouts, while daughter Alice – also a service police officer – is engaged to Keedy. Edward Marston

Edward Marston

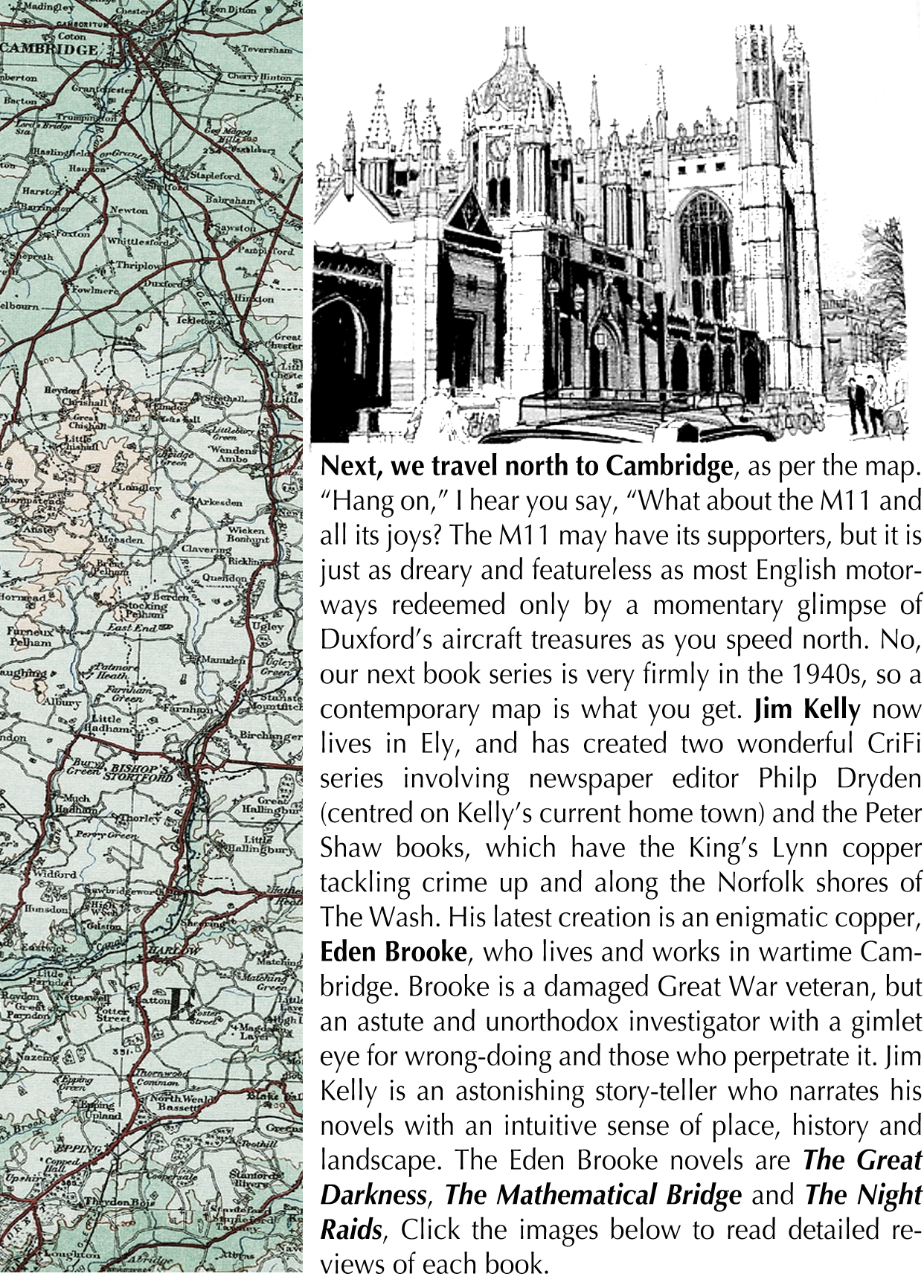

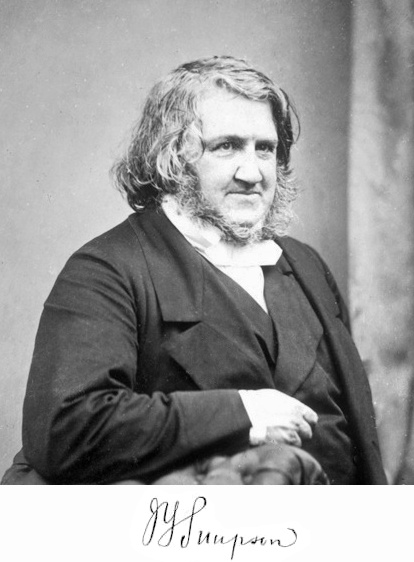

Ambrose Parry is the pseudonym used by husband and wife writing team

Ambrose Parry is the pseudonym used by husband and wife writing team  Meanwhile, Raven has met – and fallen in love with – Eugenie Todd, the beautiful and intelligent daughter of another Edinburgh doctor, and has also become involved in a murder mystery. Sir Ainsley Douglas, a powerful and influential man of means has been found dead, and the post mortem reveals traces of arsenic in his stomach. His wastrel son Gideon is arrested on suspicion of poisoning his father, with whom he has had a fairly unpleasant falling-out. Raven is an old acquaintance – but far from a friend – of Gideon. The two knew each other from university and Raven has a very low opinion of his former fellow student, and is very surprised when he is summoned to Gideon’s prison cell and asked if he will investigate Sir Ainsley’s death.

Meanwhile, Raven has met – and fallen in love with – Eugenie Todd, the beautiful and intelligent daughter of another Edinburgh doctor, and has also become involved in a murder mystery. Sir Ainsley Douglas, a powerful and influential man of means has been found dead, and the post mortem reveals traces of arsenic in his stomach. His wastrel son Gideon is arrested on suspicion of poisoning his father, with whom he has had a fairly unpleasant falling-out. Raven is an old acquaintance – but far from a friend – of Gideon. The two knew each other from university and Raven has a very low opinion of his former fellow student, and is very surprised when he is summoned to Gideon’s prison cell and asked if he will investigate Sir Ainsley’s death.

Quinn and his sergeants – Inchball and Macadam – are The Special Crimes Department of the Metropolitan Police. This department has a passing resemblance to Christopher Fowler’s

Quinn and his sergeants – Inchball and Macadam – are The Special Crimes Department of the Metropolitan Police. This department has a passing resemblance to Christopher Fowler’s

Rather

Rather

The narrator is Norman Barnett, William Arrowood’s equally impoverished assistant. Neither man is a stranger to tragedy. Barnett’s wife, ‘Mrs B’ died some months previously, while Isabel Arrowood left her husband to live with a richer man in Cambridge. He died from cancer, leaving her with his baby in her womb. She has since been taken back by her husband, but all is far from well between them. We are in the final years of the 19th century, a few decades since Gustave Doré produced his memorable – and haunting – engravings of the darker side of London, but Arrowood’s London is hardly a shade lighter. Poverty, death and illness are everywhere – in the next room, or just around the corner.

The narrator is Norman Barnett, William Arrowood’s equally impoverished assistant. Neither man is a stranger to tragedy. Barnett’s wife, ‘Mrs B’ died some months previously, while Isabel Arrowood left her husband to live with a richer man in Cambridge. He died from cancer, leaving her with his baby in her womb. She has since been taken back by her husband, but all is far from well between them. We are in the final years of the 19th century, a few decades since Gustave Doré produced his memorable – and haunting – engravings of the darker side of London, but Arrowood’s London is hardly a shade lighter. Poverty, death and illness are everywhere – in the next room, or just around the corner.