Two cracking new hardbacks arrived last week, one written by Lesley Kara, whose previous four domestic psychological thrillers have all been best-sellers and, the other by a writer who has created one of the most original amateur detectives that I have encountered. It has been five years since we had a Merrily Watkins novel from Phil Rickman, but now he brings her back in The Fever of the World.

THE APARTMENT UPSTAIRS by Lesley Kara

Lesley Kara (left) specialises in creating tension between ordinary people in humdrum surroundings – in other words, normal circumstances experienced by the vast majority of us. I reviewed her excellent debut novel The Rumour, and her new book is centred around – as the name suggests – a murder that took place above Scarlett’s flat. The victim was her aunt, and as Scarlett tries to live as normal a life as possible with such a terrible event – almost literally – hanging over her head, it is up to her to make the funeral arrangements for her relative. As she does so, she meets Dee, the funeral director. Dee has problems of her own, but an unexpected link binds the two women together, and both are now in terrible danger. The Apartment Upstairs will be published by Bantam Press on 23rd June.

Lesley Kara (left) specialises in creating tension between ordinary people in humdrum surroundings – in other words, normal circumstances experienced by the vast majority of us. I reviewed her excellent debut novel The Rumour, and her new book is centred around – as the name suggests – a murder that took place above Scarlett’s flat. The victim was her aunt, and as Scarlett tries to live as normal a life as possible with such a terrible event – almost literally – hanging over her head, it is up to her to make the funeral arrangements for her relative. As she does so, she meets Dee, the funeral director. Dee has problems of her own, but an unexpected link binds the two women together, and both are now in terrible danger. The Apartment Upstairs will be published by Bantam Press on 23rd June.

THE FEVER OF THE WORLD by Phil Rickman

For the uninitiated, Merrily Watkins is a single mum, and vicar of a village in Herefordshire. She also serves as Diocesan Deliverance Consultant – aka an exorcist. The series began in 1998 with The Wine of Angels, and seemed to have terminated rather abruptly with All of a Winter’s Night in 2017. A new book titled For The Hell of It was billed to come out in 2020, but this seems to have been reimagined as The Fever of the World. Here, Merrily becomes involved in a murder investigation led by local copper David Vaynor who, in a previous life, was an expert in the poetry of William Wordsworth. Aficionados of the work of Wordsworth may well recognise the provenance of the book’s title, taken from the poem composed on the banks of the River Wye near Tintern Abbey:

For the uninitiated, Merrily Watkins is a single mum, and vicar of a village in Herefordshire. She also serves as Diocesan Deliverance Consultant – aka an exorcist. The series began in 1998 with The Wine of Angels, and seemed to have terminated rather abruptly with All of a Winter’s Night in 2017. A new book titled For The Hell of It was billed to come out in 2020, but this seems to have been reimagined as The Fever of the World. Here, Merrily becomes involved in a murder investigation led by local copper David Vaynor who, in a previous life, was an expert in the poetry of William Wordsworth. Aficionados of the work of Wordsworth may well recognise the provenance of the book’s title, taken from the poem composed on the banks of the River Wye near Tintern Abbey:

“In darkness and amid the many shapes

Of joyless daylight; when the fretful stir

Unprofitable, and the fever of the world,

Have hung upon the beatings of my heart.”

My appreciation of the Merrily Watkins novels is here, and I am anxious to see what has become of the repertory company of characters Rickman (above right) used in the earlier novels. The book is published by Atlantic Books, and will be out on 16th June.

There are three narrative viewpoints;

There are three narrative viewpoints;  Her estranged sister, Sadie,

Her estranged sister, Sadie,

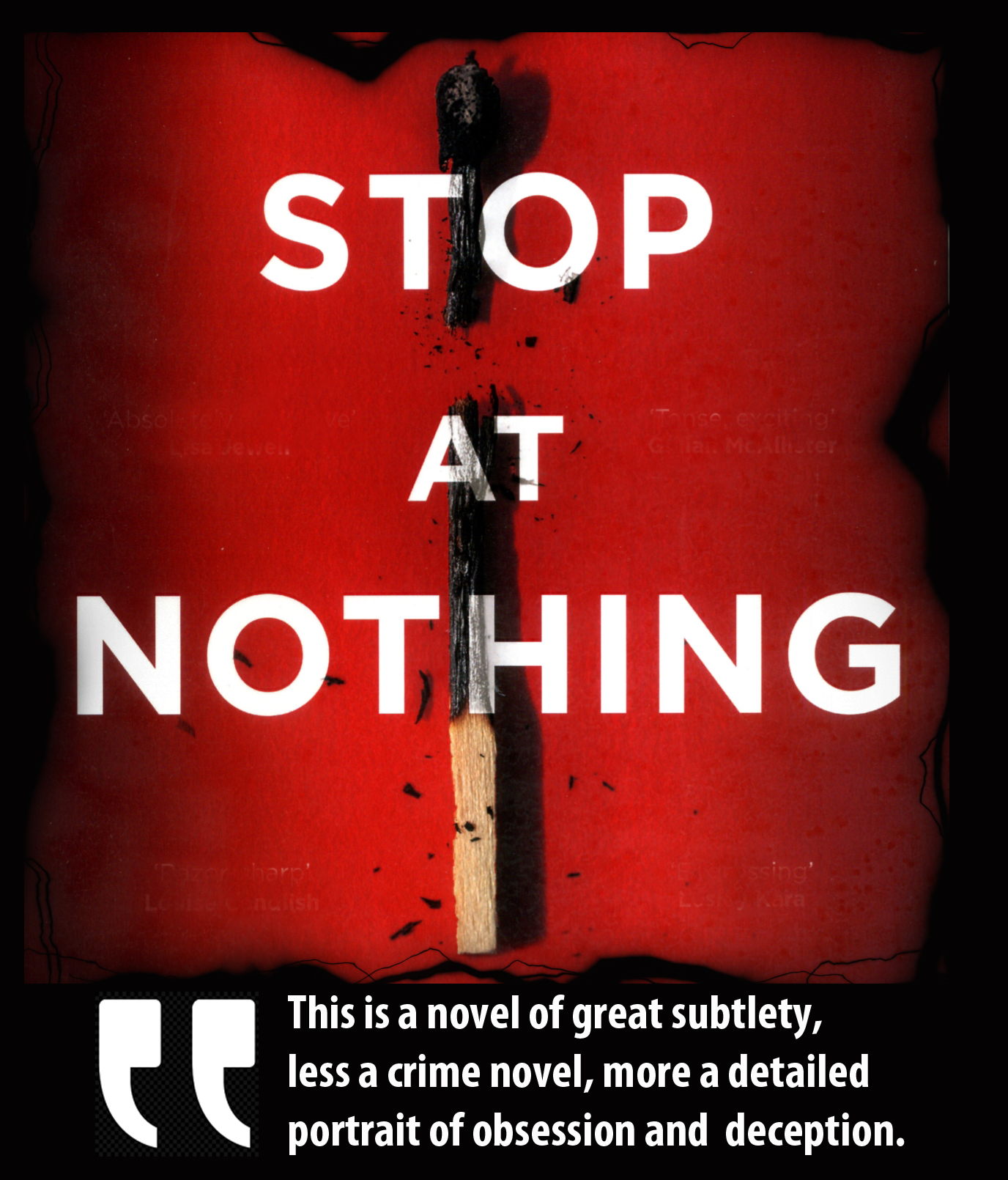

Poor Tessa is a mess, actually. Struggling to cope with the physical and psychological effects of the menopause and her self-esteem battered by redundancy, she is prey to all manner of fancies, midnight imaginings and “the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.” Much of Stop At Nothing is pure anxiety porn, as Tessa makes bad judgment after bad judgment, wrong call after wrong call. Readers will see the picture – at least part of it – way, way before she does, and in places the narrative reminded me of the frequent moments in Hammer horror films where the heroine (usually scantily clad) insists on going down into the cellar clutching only a flickering candle. We want to grab Tessa by the arm and say. “Do. Not. Do. This!”

Poor Tessa is a mess, actually. Struggling to cope with the physical and psychological effects of the menopause and her self-esteem battered by redundancy, she is prey to all manner of fancies, midnight imaginings and “the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.” Much of Stop At Nothing is pure anxiety porn, as Tessa makes bad judgment after bad judgment, wrong call after wrong call. Readers will see the picture – at least part of it – way, way before she does, and in places the narrative reminded me of the frequent moments in Hammer horror films where the heroine (usually scantily clad) insists on going down into the cellar clutching only a flickering candle. We want to grab Tessa by the arm and say. “Do. Not. Do. This!” Personally, I warmed to Tessa – and her unfailing knack of getting things wrong – much more when her relationship with her elderly parents moved to centre stage. The tragedy of dementia is a natural cruelty that makes even the most devout religious person want to howl with rage at the heavens, and Tammy Cohen (right) handles this poignant mix of frustration and fury with a deft touch.

Personally, I warmed to Tessa – and her unfailing knack of getting things wrong – much more when her relationship with her elderly parents moved to centre stage. The tragedy of dementia is a natural cruelty that makes even the most devout religious person want to howl with rage at the heavens, and Tammy Cohen (right) handles this poignant mix of frustration and fury with a deft touch.

There is, however, that strange smell. A certain je ne sais quoi which will not go away, despite the couple’s best efforts. When Jack finally plucks up the courage to climb up into the roof space, he finds the physical source of the smell but unpleasant as that is, he also finds something which is much more disturbing. Simon Lelic (right) then has us walking on pins and needles as he unwraps a plot which involves obsession, child abuse, psychological torture and plain old-fashioned violence.

There is, however, that strange smell. A certain je ne sais quoi which will not go away, despite the couple’s best efforts. When Jack finally plucks up the courage to climb up into the roof space, he finds the physical source of the smell but unpleasant as that is, he also finds something which is much more disturbing. Simon Lelic (right) then has us walking on pins and needles as he unwraps a plot which involves obsession, child abuse, psychological torture and plain old-fashioned violence.

Kristy puts food on the table and tries to make sure that Ryan isn’t disadvantaged. She has a job, and it is one that demands every ounce of her compassion and every droplet of her sang froid. Her official title? Public Information Officer for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. If that sounds like some bureaucratic walk-in-the-park, think again. Acting as mediator between inmates, the press and the prison system is one thing, but remember that The Lone Star State is one of the thirty one American states which retains the death penalty. Consequently, Kristy not only has to manage the fraught liaison between prisoners on death row and the media, but she is also required to be an official witness at executions.

Kristy puts food on the table and tries to make sure that Ryan isn’t disadvantaged. She has a job, and it is one that demands every ounce of her compassion and every droplet of her sang froid. Her official title? Public Information Officer for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. If that sounds like some bureaucratic walk-in-the-park, think again. Acting as mediator between inmates, the press and the prison system is one thing, but remember that The Lone Star State is one of the thirty one American states which retains the death penalty. Consequently, Kristy not only has to manage the fraught liaison between prisoners on death row and the media, but she is also required to be an official witness at executions. It will come as no surprise to learn that Hollie Overton (right) is an experienced writer for TV. In The Walls every set-piece, every scene is intensely visual and immediate. With consummate cleverness she sets up two story lines which at first run parallel, but then converge. Two men. One is definitely guilty. One possibly innocent. Both are condemned to death. One by the State of Texas. The other by his battered wife.

It will come as no surprise to learn that Hollie Overton (right) is an experienced writer for TV. In The Walls every set-piece, every scene is intensely visual and immediate. With consummate cleverness she sets up two story lines which at first run parallel, but then converge. Two men. One is definitely guilty. One possibly innocent. Both are condemned to death. One by the State of Texas. The other by his battered wife.

Back in late 2016, I had the pleasure of listening to T A Cotterell read an extract from his debut novel, What Alice Knew. He made it clear that this was a book about secrets, and about that strange beast, family life. Family life. The words are anodyne, mild and reassuring, but we all know that many families are not what they seem to be to an outsider. Cotterell’s question, though, is simply this: “How well do members of a family know each other?”

Back in late 2016, I had the pleasure of listening to T A Cotterell read an extract from his debut novel, What Alice Knew. He made it clear that this was a book about secrets, and about that strange beast, family life. Family life. The words are anodyne, mild and reassuring, but we all know that many families are not what they seem to be to an outsider. Cotterell’s question, though, is simply this: “How well do members of a family know each other?” From this point on, the dreamy soft-focus life of the Sheahan family descends into a nightmare reality, all jagged edges and harshly grating contrasts. The visual metaphor is actually totally appropriate, as one of the great strengths of the novel is how Alice sees much of life through her painterly eyes. Rose madder, cadmium yellow, viridian, alizarin crimson and flake white. Alice’s world is the world of the quaintly named oil paints on her palette. It came as no surprise to me to learn that Cotterell (right) studied History of Art at Cambridge.

From this point on, the dreamy soft-focus life of the Sheahan family descends into a nightmare reality, all jagged edges and harshly grating contrasts. The visual metaphor is actually totally appropriate, as one of the great strengths of the novel is how Alice sees much of life through her painterly eyes. Rose madder, cadmium yellow, viridian, alizarin crimson and flake white. Alice’s world is the world of the quaintly named oil paints on her palette. It came as no surprise to me to learn that Cotterell (right) studied History of Art at Cambridge.