Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

Leeds, March 1920. Tom Harper is Chief Constable of the City force and, with just six weeks until his retirement, he is dearly hoping for a quiet ride home for the final furlong of what has been a long and distinguished career. His hopes are dashed, however, when he is summoned to the office of Alderman Ernest Thompson, the combative, blustering – but very powerful – leader of the City Council. Thompson has one last task for Harper, and it is a very delicate one. The politician has fallen a trap that is all too familiar to many elderly men of influence down the years. He has, shall we say, been indiscreet with a beautiful but much younger woman, Charlotte Radcliffe. Letters that he foolishly wrote to her have “gone missing” and now he has an anonymous note demanding money – or else his reputation will be ruined. He wants Harper to solve the case, but keep everything completely off the record. Grim-faced, Harper has little choice but to agree. It is due to Thompson’s support and encouragement that he is ending his career as Chief Constable, with a comfortable pension and an untarnished reputation. He chooses a small group of trusted colleagues, swears them to secrecy, and sets about the investigation.

He soon has other things to worry about. A quartet of young armed men robs a city centre jewellers, terrifying the staff by firing a shot into the ceiling. They strike again, but this time with fatal consequences. A bystander tries to intervene, and is shot dead for his pains. Many readers will have been following this excellent series for some time, and will know that tragedy has struck the Harper family. Tom’s wife Annabelle has what we know now as dementia, and requires constant care. Their daughter Mary is a widow. Her husband Len is one of the 72000 men who fought and died on the Somme, but have no known grave, and no memorial excep tfor a name on the Thiepval Memorial to The Missing.. Unlike many widows, however, she has been able to rebuild her life, and now runs a successful secretarial agency. Leeds, however, like so many communities, is no place fit for heroes:

“‘Times are hard.’

“I know,” Harper agreed.

It was there in the bleak faces of the men, the worn-down looks of their wives, the hunger that kept the children thin. The wounded ex-servicemen reduced to begging on the streets. Things hadn’t changed much from when he was young. Britain had won the war but forgotten its own people.”

Nickson’s descriptions of his beloved Leeds are always powerful, but here he describes a city – like many others – reeling from a double blow. As if the carnage of the Great War were not enough, the Gods had another spiteful trick up their sleeves in the shape of Spanish Influenza, which killed 228000 people across the country. Many people are still wearing gauze masks in an attempt to ward off infection.

The hunt for the jewel robbers and Ernest Jackson’s letters continues almost to the end of the book and, as ever, Nickson tells a damn good crime story; for me however, the focus had long since shifted elsewhere. This book is all about Tom and Annabelle Harper. Weather-wise, spring is definitely in the air, as bushes and trees come back to life after the bareness of winter, but there is a distinctly autumnal air about what is happening on the page. Harper is, like Tennyson’s Ulysses, not the man he was.

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will.

As he tries to help at the scene of a crime, he reflects:

“There was nothing he could do to help here; he was just another old man cluttering up the pavement and stopping the inspector from doing his job.”

As for Annabelle, the lovely, brave and vibrant woman of the earlier books, little is left:

“The memories would remain. She’d have them too, but they were tucked away in pockets that were gradually being sewn up. All her past was being stolen from her. And he couldn’t stop the theft.”

This is a magnificent and poignant end to the finest series of historical crime fiction I have ever read. It is published by Severn House and will be available on 5th September. For more about the Tom Harper novels, click this link.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate. company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

England, 1923. Like thousands upon thousands of other young women, Esme Nicholls is a widow. Husband Alec lies in a functional grave in a military cemetery in Flanders. His face remains in a few photographs, and in her memories. Left penniless, she ekes out a living by writing a nature-notes feature for a northern provincial newspaper, and serving as a personal assistant to an older widow, Mrs Pickering. Mrs P has the advantage of being able to visit her husband’s grave whenever she wants, as he was not a victim of the war.

England, 1923. Like thousands upon thousands of other young women, Esme Nicholls is a widow. Husband Alec lies in a functional grave in a military cemetery in Flanders. His face remains in a few photographs, and in her memories. Left penniless, she ekes out a living by writing a nature-notes feature for a northern provincial newspaper, and serving as a personal assistant to an older widow, Mrs Pickering. Mrs P has the advantage of being able to visit her husband’s grave whenever she wants, as he was not a victim of the war. Caroline Scott (right) treats us to a high summer in Cornwall, where every flower, rustle of leaves in the breeze and flit of insect is described with almost intoxicating detail. Readers who remember her previous novel When I Come Home Again will be unsurprised by this detail. In the novel, she references that greatest of all poet of England’s nature, John Clare, but I also sense something of Matthew Arnold’s poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis, so memorably set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

Caroline Scott (right) treats us to a high summer in Cornwall, where every flower, rustle of leaves in the breeze and flit of insect is described with almost intoxicating detail. Readers who remember her previous novel When I Come Home Again will be unsurprised by this detail. In the novel, she references that greatest of all poet of England’s nature, John Clare, but I also sense something of Matthew Arnold’s poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis, so memorably set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams.

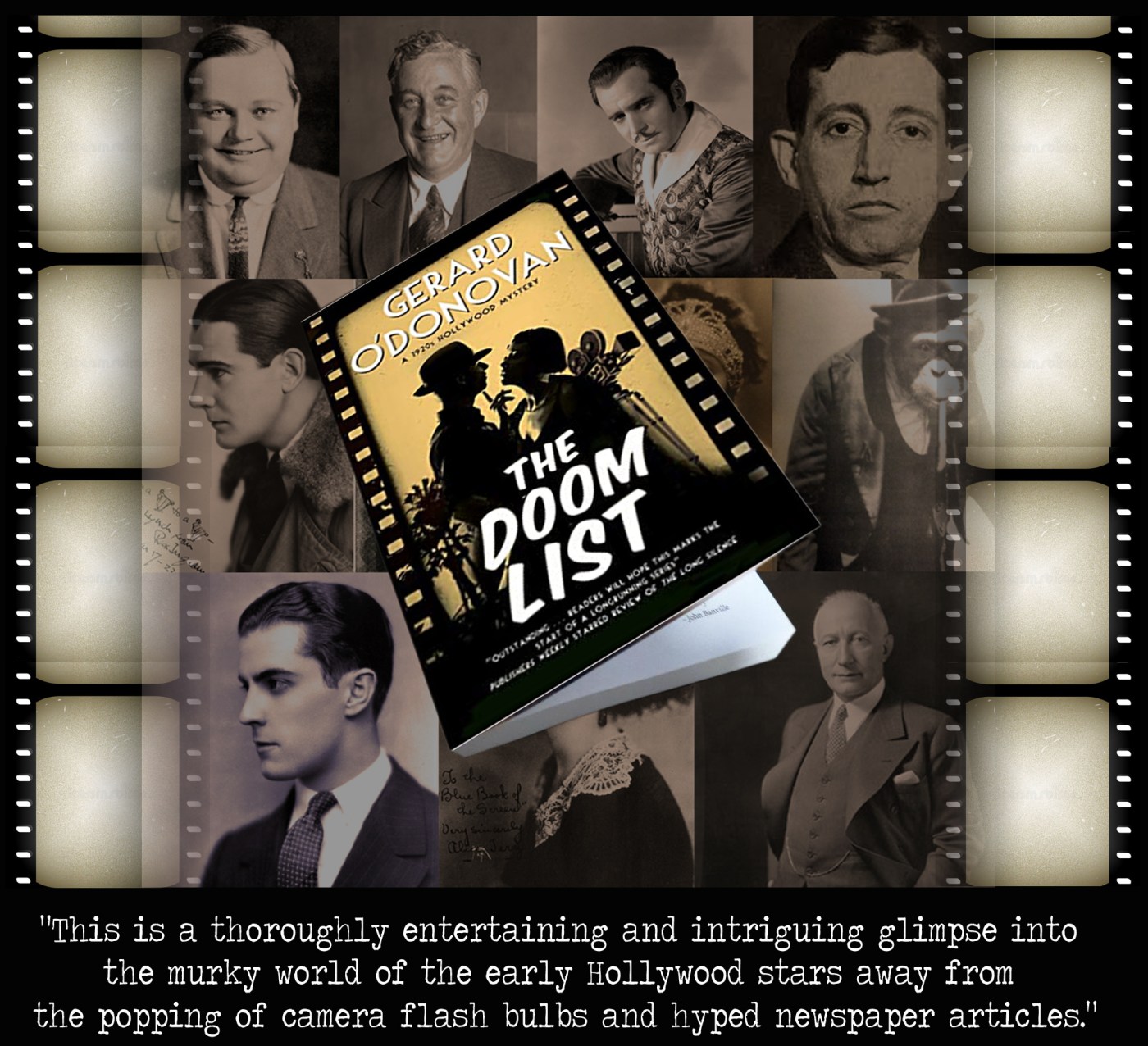

Former city cop Collins has earned a reputation among movie producers and stars as a man who gets things done, but in a discreet way, and here he becomes involved in getting to the bottom of a nasty blackmail case involving one of Hollywood’s rising stars. José Ramón Gil Samaniego is a young man who was to become better know as Ramon Novarro, star of many hit movies, and an heir to the throne of screen heart-throb vacated by Rudolf Valentino after his untimely death. O’Donovan peoples his story with actual real life characters as far as possible, and it is a winning formula. Samaniego is in trouble because there are intimate photographs of him taken a notorious club for homosexuals. Both he and his studio bosses are desperate that these photos and the negatives are found and destroyed.

Former city cop Collins has earned a reputation among movie producers and stars as a man who gets things done, but in a discreet way, and here he becomes involved in getting to the bottom of a nasty blackmail case involving one of Hollywood’s rising stars. José Ramón Gil Samaniego is a young man who was to become better know as Ramon Novarro, star of many hit movies, and an heir to the throne of screen heart-throb vacated by Rudolf Valentino after his untimely death. O’Donovan peoples his story with actual real life characters as far as possible, and it is a winning formula. Samaniego is in trouble because there are intimate photographs of him taken a notorious club for homosexuals. Both he and his studio bosses are desperate that these photos and the negatives are found and destroyed.

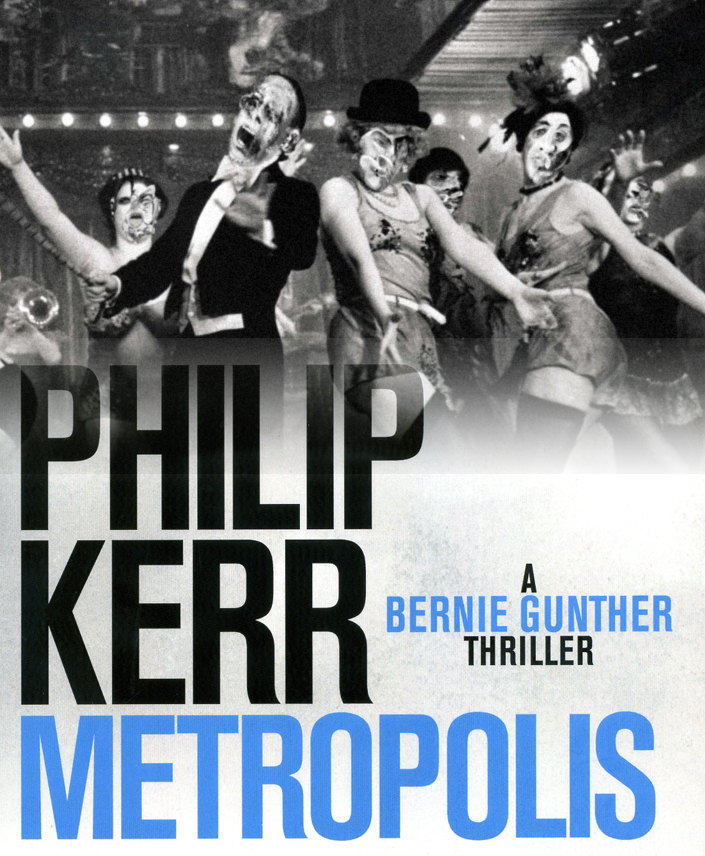

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth?

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth? Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

Forced to play cherchez-la-femme, the detectives stumble down one blind alley after another, but as they do so they learn a few home truths about the fate of the young men who went to fight in the war-to-end-all-wars, and returned home to find that their birthplace was not the ‘land fit for heroes’ glibly promised by politicians. There is a peacetime army with no place for young officers whose courage was welcome in the trenches, but whose humble upbringing is now seen as an embarrassment as the cigars are lit, and the port passed in the correct direction at mess dinners. Such young men, not all heroes, but men nevertheless, are forced to find civilian employment which is neither honest, decent nor lawful.

Forced to play cherchez-la-femme, the detectives stumble down one blind alley after another, but as they do so they learn a few home truths about the fate of the young men who went to fight in the war-to-end-all-wars, and returned home to find that their birthplace was not the ‘land fit for heroes’ glibly promised by politicians. There is a peacetime army with no place for young officers whose courage was welcome in the trenches, but whose humble upbringing is now seen as an embarrassment as the cigars are lit, and the port passed in the correct direction at mess dinners. Such young men, not all heroes, but men nevertheless, are forced to find civilian employment which is neither honest, decent nor lawful. Graham Ison is a master story-teller. The Hardcastle books contain no literary flourishes or stylistic tricks – just credible characters, excellent period detail and an engaging plot. Cosy? Perhaps, in the sense that we know how Hardcastle and his officers are going to react to any given situation, and their habits and small prejudices remain unchanged. Comfortable? Only because novels don’t always need to shock or challenge; neither do they always benefit from graphic descriptions of the damage humans can sometimes inflict on one another. Ison (right) credits his readers with having imaginations; he never gilded the lily of English life in the earlier Hardcastle cases which took place during The Great War, and he doesn’t start now, nearly a decade after the final shots were fired. The suffering and trauma of those four terrible years didn’t end at the eleventh hour on that eleventh day; they cast a long and sometimes baleful shadow which frames much of the action of this novel.

Graham Ison is a master story-teller. The Hardcastle books contain no literary flourishes or stylistic tricks – just credible characters, excellent period detail and an engaging plot. Cosy? Perhaps, in the sense that we know how Hardcastle and his officers are going to react to any given situation, and their habits and small prejudices remain unchanged. Comfortable? Only because novels don’t always need to shock or challenge; neither do they always benefit from graphic descriptions of the damage humans can sometimes inflict on one another. Ison (right) credits his readers with having imaginations; he never gilded the lily of English life in the earlier Hardcastle cases which took place during The Great War, and he doesn’t start now, nearly a decade after the final shots were fired. The suffering and trauma of those four terrible years didn’t end at the eleventh hour on that eleventh day; they cast a long and sometimes baleful shadow which frames much of the action of this novel.

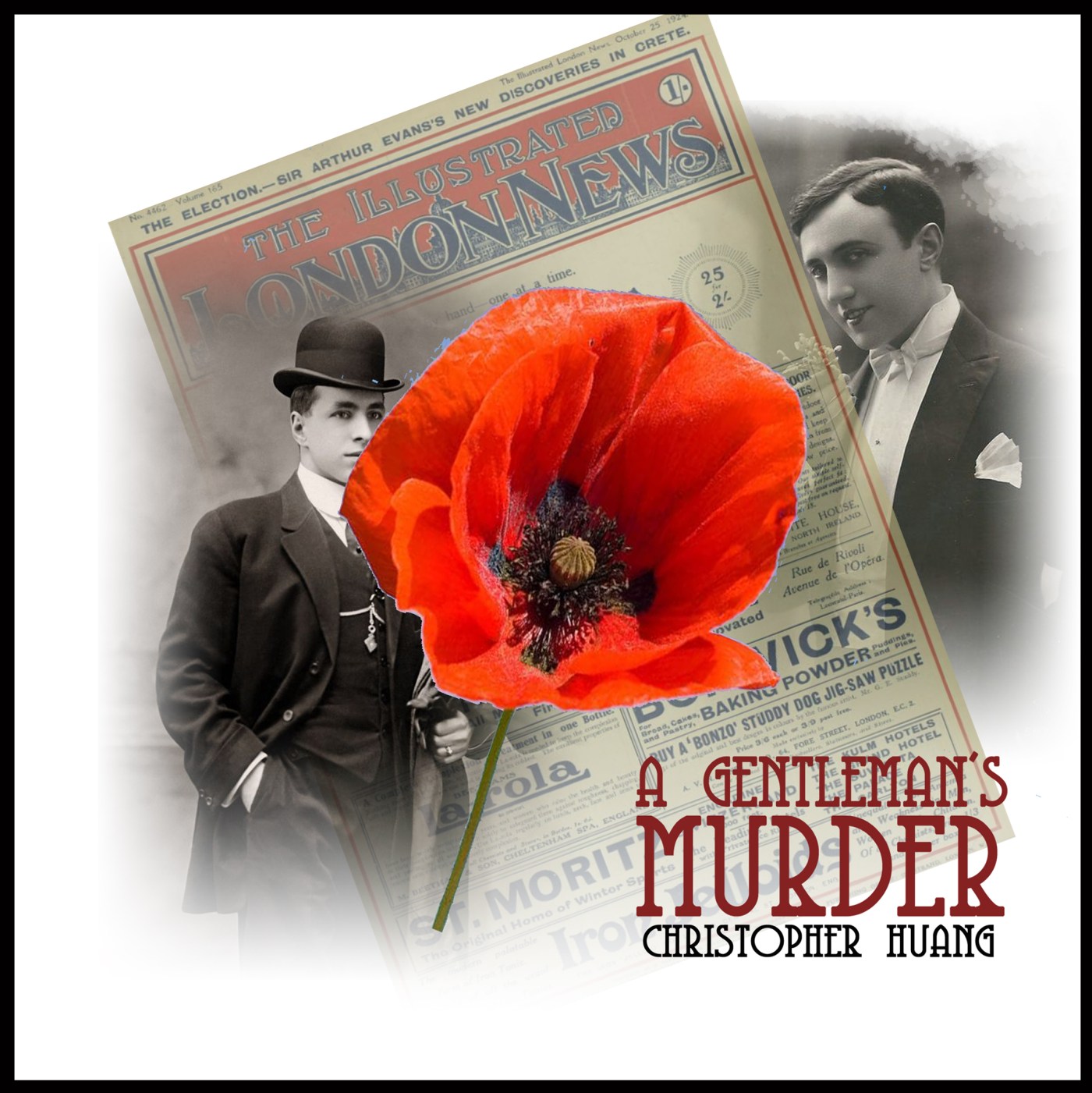

Eric Peterkin is one such and, although he carries his rank with pride, he is just a little different, and he is viewed with some disdain by certain fellow members and simply tolerated by others. Despite generations of military Peterkins looking down from their portraits in the club rooms, Eric is what is known, in the language of the time, a half-caste. His Chinese mother has bequeathed him more than enough of the characteristics of her race for the jibe, “I suppose you served in the Chinese Labour Corps?” to become commonplace.

Eric Peterkin is one such and, although he carries his rank with pride, he is just a little different, and he is viewed with some disdain by certain fellow members and simply tolerated by others. Despite generations of military Peterkins looking down from their portraits in the club rooms, Eric is what is known, in the language of the time, a half-caste. His Chinese mother has bequeathed him more than enough of the characteristics of her race for the jibe, “I suppose you served in the Chinese Labour Corps?” to become commonplace. Christopher Huang (right) was born and raised in Singapore where he served his two years of National Service as an Army Signaller. He moved to Canada where he studied Architecture at McGill University in Montreal. Huang currently lives in Montreal.. Judging by this, his debut novel, he also knows how to tell a story. He gives us a fascinating cast of gentleman club members, each of them worked into the narrative as a murder suspect. We have Mortimer Wolfe – “sleek, dapper and elegant, hair slicked down and gleaming like mahogany”, club President Edward Aldershott, “Tall, prematurely grey and with a habit of standing perfectly still …like a bespectacled stone lion,” and poor, haunted Patrick “Patch” Norris with his constant, desperate gaiety.

Christopher Huang (right) was born and raised in Singapore where he served his two years of National Service as an Army Signaller. He moved to Canada where he studied Architecture at McGill University in Montreal. Huang currently lives in Montreal.. Judging by this, his debut novel, he also knows how to tell a story. He gives us a fascinating cast of gentleman club members, each of them worked into the narrative as a murder suspect. We have Mortimer Wolfe – “sleek, dapper and elegant, hair slicked down and gleaming like mahogany”, club President Edward Aldershott, “Tall, prematurely grey and with a habit of standing perfectly still …like a bespectacled stone lion,” and poor, haunted Patrick “Patch” Norris with his constant, desperate gaiety.