It seems like half a lifetime since there was a Merrily Watkins novel – it was All of a Winter’s Night back in 2017 (click the title to read my review) and there has been one hell of a lot of water under the bridge for all of us since then including, sadly, Phil Rickman suffering serious illness. His many fans will join me in hoping that he is on the mend, and at last we have a new book! Old Ledwardine hands won’t need reminding, but for newcomers this graphic may be helpful.

Now, as another celebrated solver of mysteries once said, “The game’s afoot!” We are in relatively modern times, March 2020, and the Covid Curse has begun to cast its awful spell. The senior Anglican clergy, including the Bishop of Hereford, are relentlessly determined to be woker than woke, and have decided that exorcism – or, to use the other term, deliverance – is the stuff or the middle ages, and clergy are being advised to refer any strange events to the NHS mental health teams. This, of course, puts Merrily Watkins’ ‘night job’ under threat. She and her mentor Huw Owen know that some people experience events which cannot simply be the result of their poor mental health.

The Merrily Watkins novels have a template. This is not to say they are formulaic in a derogatory sense. The template involves a crime – most often a murder or mysterious death. This is investigated by the West Mercia police, usually in the form of Inspector Frannie Bliss. The investigation then reveals what appear to be supernatural or paranormal characteristics, which then secures the involvement of the Rev. Merrily Watkins, vicar of Ledwardine.

Here, a prominent Hereford estate agent and enthusiastic rock climber, Peter Portis, has plummeted to his death from one of the peaks of a Wye Valley rock formation known as The Seven Sisters. A tragic accident? Perhaps. A parallel plot develops. In another parish, the vicar – a former TV actor called Arlo Ripley – has asked Merrily for help. One of his flock has reported seeing the spectre of a young girl and isn’t sure what to do. Enter, stage left, William Wordsworth. Not in person, obviously, but on a visit to the Wye Valley, the poet apparently met a young girl who claimed she could communicate with her dead siblings. The result was his poem We are Seven. That, and Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey are the spine of this novel. Click the titles, and you will see the full texts of the poems. The girl who has entered the life of Maya Madden – a TV producer renting a cottage in the village of Goodrich – seems to be one and the same as Wordsworth’s muse.

Enter, stage right, another Hereford copper, David Vaynor. Nicknamed ‘Darth’ by his boss Frannie Bliss, he is an unusual chap. For starters, he has a PhD in English literature, and his thesis was based on Wordsworth’s time in Herefordshire. To add to the strangeness, while he was researching his work, he went into what is known as King Arthur’s Cave, a natural cavity in the rock close to where Portis met his end. While he was in there, he has a residual memory of sinking – exhausted – into what was a natural rock chair – and then being visited by a succubus.¹

Yes, yes, – the poor lad was tired, a bit hormonal and having bad dreams. But wait. As Vaynor is doing his job, and interviewing those who knew Portis, he meets his daughter in law, and she reminds him horribly of the woman he ‘met’ on that fateful afternoon in King Arthur’s Cave.

This has everything Merrily Watkins fans – and newcomers to the series – could want. A deep sense of unease, matchless atmosphere – the funeral held in fading light in a virtually disused churchyard, for example – the wonderful ambiguity of Rickman’s approach to the supernatural – we never actually see the phantoms, but we are aware that other people have – the wonderful repertory company of characters who interact so well, and also a deep sense that the past is never far away. There is also a palpable sense of irony that ‘the fever of the world’ is not just a metaphor from a Wordsworth poem, but was actually happening as the coronavirus took hold.

The Fever of the World is published by Corvus/Atlantic books and is out now.

¹A succubus is a demon or supernatural entity in folklore, in female form, that appears in dreams to seduce men, usually through sexual activity.

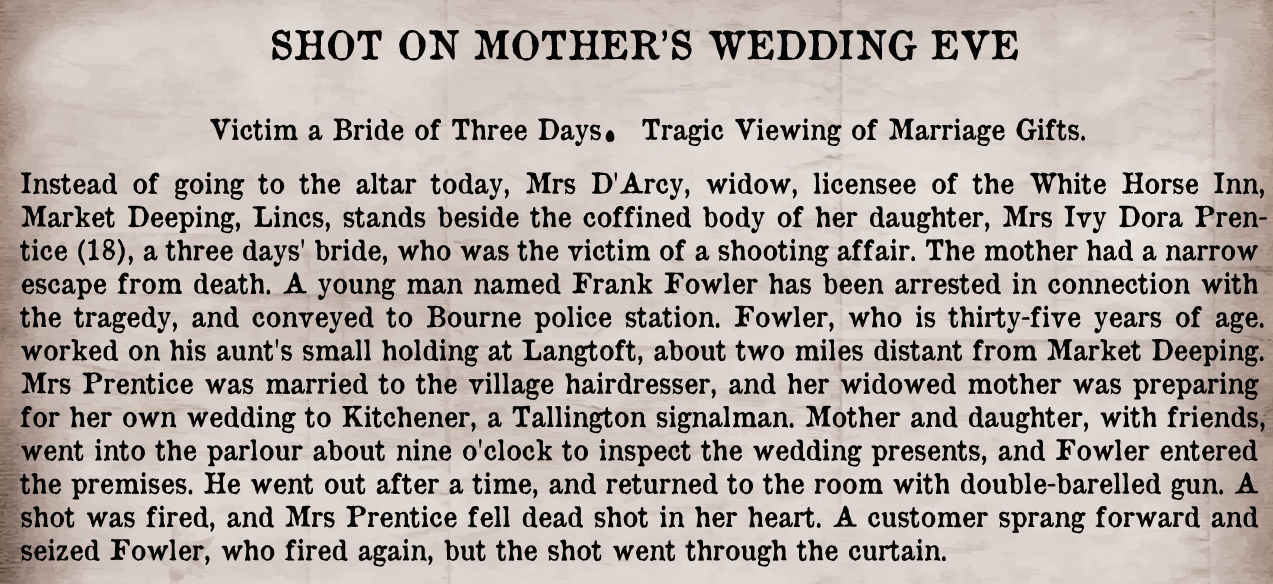

By 1901, however, he is still living in Langtoft, but with his grandparents Henry and Alice Rosling. His parents, along with daughter Henrietta and a younger son, Robert, had moved to Pickworth, 8 miles east of Grantham. One can only speculate why they left Frank – still only fourteen – behind. It is possible that there was no sinister reason behind this, as by then he may have been working, but it is not mentioned on the census return. In 1911 he is still living with his grandfather – now a widower – and certainly working on a farm. It seems he was either conscripted or joined up to fight in The Great War (pictured left), survived, and returned to Lincolnshire. In 1922 he was managing a farm owned by his aunt, a Mrs Ormer, and was a regular customer at The White Horse. It also seems he had developed an interest in the landlady’s daughter – Ivy Dora D’Arcy.

By 1901, however, he is still living in Langtoft, but with his grandparents Henry and Alice Rosling. His parents, along with daughter Henrietta and a younger son, Robert, had moved to Pickworth, 8 miles east of Grantham. One can only speculate why they left Frank – still only fourteen – behind. It is possible that there was no sinister reason behind this, as by then he may have been working, but it is not mentioned on the census return. In 1911 he is still living with his grandfather – now a widower – and certainly working on a farm. It seems he was either conscripted or joined up to fight in The Great War (pictured left), survived, and returned to Lincolnshire. In 1922 he was managing a farm owned by his aunt, a Mrs Ormer, and was a regular customer at The White Horse. It also seems he had developed an interest in the landlady’s daughter – Ivy Dora D’Arcy.

That is just a quick sample of the whip-crack dialogue in the book, which fizzles and sparks like electricity across terminals. Very soon Mari and Derek realise that the blackmailed judge is also connected to the unsolved murder of a French duel-passport student, Sophie Michaud, and the fate of two women journalists who investigated the case, one of whom is dead and the other missing.

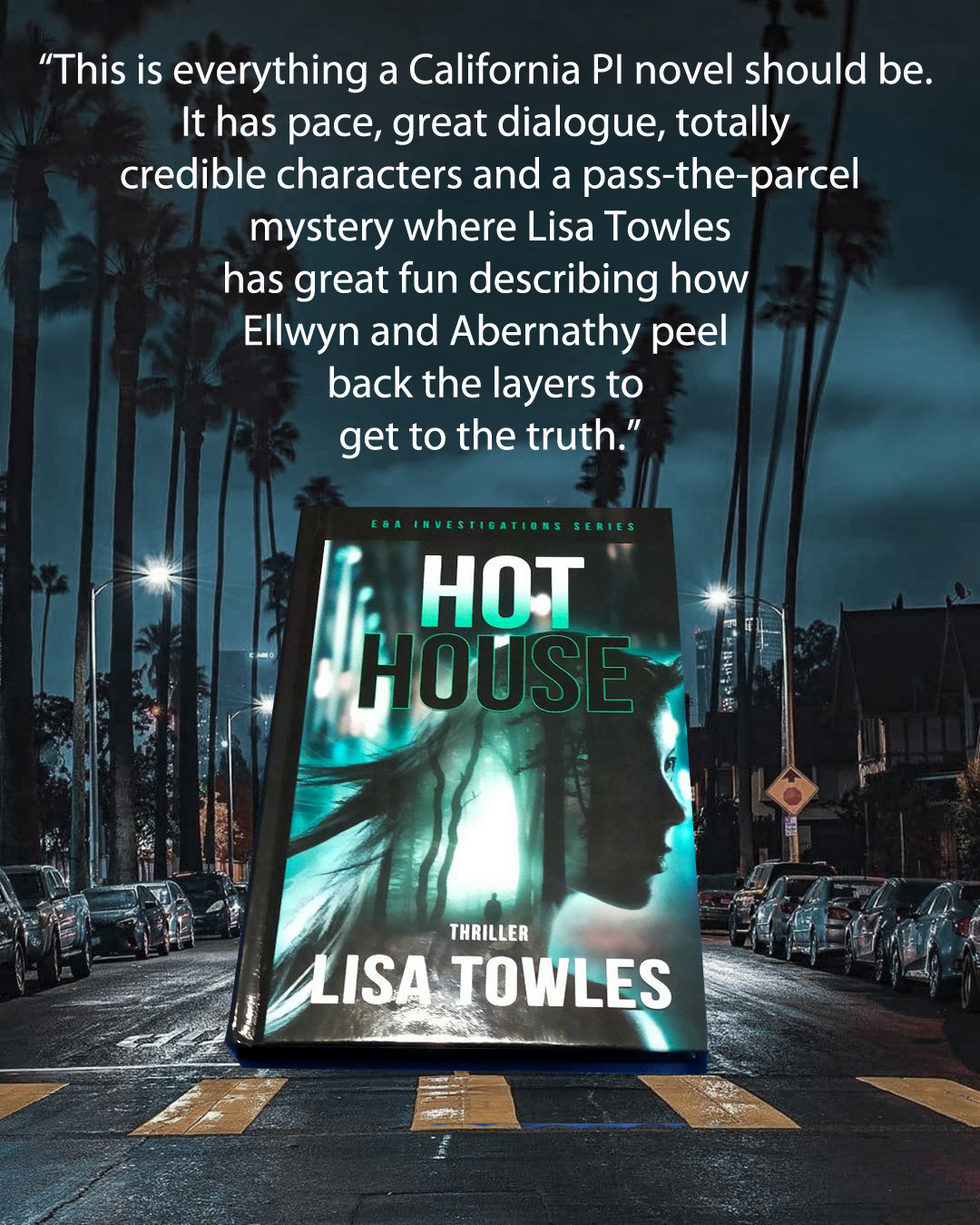

That is just a quick sample of the whip-crack dialogue in the book, which fizzles and sparks like electricity across terminals. Very soon Mari and Derek realise that the blackmailed judge is also connected to the unsolved murder of a French duel-passport student, Sophie Michaud, and the fate of two women journalists who investigated the case, one of whom is dead and the other missing. In the end, the blackmailer of the judge is located, and the killer of Sophie/Sasha is brought to justice, but with literally the last sentence, Lisa Towles poses another puzzle which will presumably be addressed in the next book. Hot House is everything a California PI novel should be. It has pace, great dialogue, totally credible characters and a pass-the-parcel mystery where Lisa Towles (right) has great fun describing how Ellwyn and Abernathy peel back the layers to get to the truth. Sure, the pair might not yet stand shoulder to shoulder with Marlowe, Spade and Archer, or even more modern characters like Bosch and Cole, but they have arrived, and something tells me they are here to stay.

In the end, the blackmailer of the judge is located, and the killer of Sophie/Sasha is brought to justice, but with literally the last sentence, Lisa Towles poses another puzzle which will presumably be addressed in the next book. Hot House is everything a California PI novel should be. It has pace, great dialogue, totally credible characters and a pass-the-parcel mystery where Lisa Towles (right) has great fun describing how Ellwyn and Abernathy peel back the layers to get to the truth. Sure, the pair might not yet stand shoulder to shoulder with Marlowe, Spade and Archer, or even more modern characters like Bosch and Cole, but they have arrived, and something tells me they are here to stay.

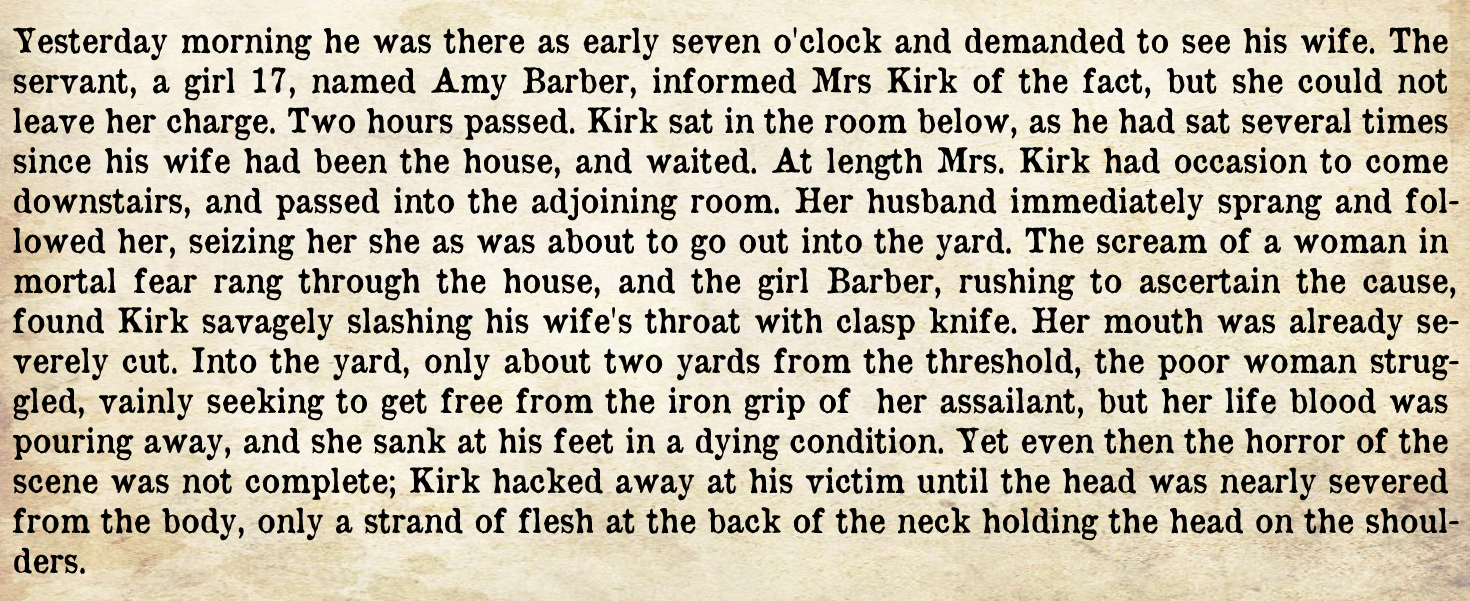

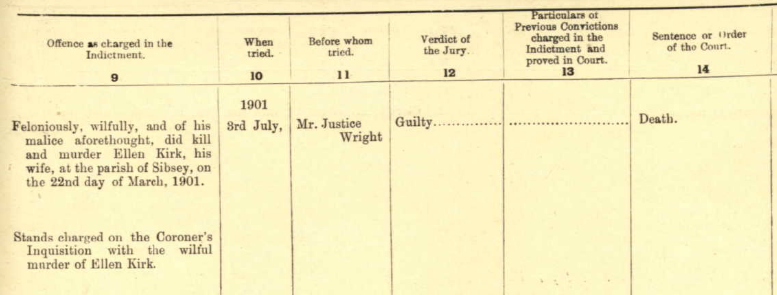

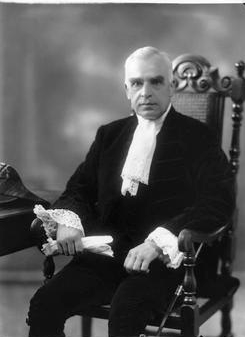

Inevitably, William Kirk was found guilty of murder, and his case was sent to the July Assizes in Lincoln. The trial, presided over by Mr Justice Wright (left) was a formality, and Kirk was sentenced to be hanged. Just days before he was due to meet James Billington for the first – and only time – the powers that be judged that he was insane at the time of the killed his wife, and he was reprieved, and sent to Broadmoor.

Inevitably, William Kirk was found guilty of murder, and his case was sent to the July Assizes in Lincoln. The trial, presided over by Mr Justice Wright (left) was a formality, and Kirk was sentenced to be hanged. Just days before he was due to meet James Billington for the first – and only time – the powers that be judged that he was insane at the time of the killed his wife, and he was reprieved, and sent to Broadmoor.

Late again! My excuse is that I am a one-man-band here at Fully Booked, and notwithstanding the occasional erudite contribution from Stuart Radmore (who has forgotten more about crime fiction than most people will ever know), there are only so many books I can read and review properly. My first experience of Peterborough copper DI Barton is the fifth of the series (written by Ross Greenwood), The Fire Killer. Peterborough is a big place, at least for us Fenland townies, but is rarely featured in CriFi novels. I am pretty sure that Peter Robinson’s DI Banks grew up there (The Summer That Never Was) and Eva Dolan’s Zigic and Ferreira books are certainly set in the city.

Late again! My excuse is that I am a one-man-band here at Fully Booked, and notwithstanding the occasional erudite contribution from Stuart Radmore (who has forgotten more about crime fiction than most people will ever know), there are only so many books I can read and review properly. My first experience of Peterborough copper DI Barton is the fifth of the series (written by Ross Greenwood), The Fire Killer. Peterborough is a big place, at least for us Fenland townies, but is rarely featured in CriFi novels. I am pretty sure that Peter Robinson’s DI Banks grew up there (The Summer That Never Was) and Eva Dolan’s Zigic and Ferreira books are certainly set in the city. Ross Greenwood (right) has fun inviting us to make out own guesses, but also makes the game a little more interesting by giving us intermittent chapters narrated by The Fire Killer, but he is very wary about giving us too many clues. The dead girl, Jess Craven had been involved with a very rich dentist with links – as a customer – to the London drug trade.

Ross Greenwood (right) has fun inviting us to make out own guesses, but also makes the game a little more interesting by giving us intermittent chapters narrated by The Fire Killer, but he is very wary about giving us too many clues. The dead girl, Jess Craven had been involved with a very rich dentist with links – as a customer – to the London drug trade.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate.

Investigator and journalist Harry Lark fought for King and Country and emerged relatively unscathed although, like so many other men, the sounds, smells and images of the trenches are ever present at the back of his mind and he has also become addicted to laudanum – a tincture of opium and alcohol. When he is contacted by a friend and benefactor, Lady Charlotte Carlisle, she tells him that she thinks she has seen a ghost. Sitting in Mayfair’s Café Boheme, she has seen a man who is the image of Captain Adrian Harcourt, a pre-war politician who was killed on the Western Front in 1918, and was engaged to be married to her daughter Ferderica. But this man is no phantom who can fade into the wallpaper. Other customers notice him. He is flesh and blood, and approaches Lady Charlotte’s table, stares into her eyes, but then leaves without saying a word. She asks Lark to investigate. company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

company, and that some seriously well-connected people have ensured that the truth about their demise has been successfully covered up. Iver’s son has been committed to an institution for mentally and physically damaged WW1 soldiers, and Filton Hall is Harry’s next port of call.

Lesley Kara (left) specialises in creating tension between ordinary people in humdrum surroundings – in other words, normal circumstances experienced by the vast majority of us. I reviewed her excellent debut novel The Rumour, and her new book is centred around – as the name suggests – a murder that took place above Scarlett’s flat. The victim was her aunt, and as Scarlett tries to live as normal a life as possible with such a terrible event – almost literally – hanging over her head, it is up to her to make the funeral arrangements for her relative. As she does so, she meets Dee, the funeral director. Dee has problems of her own, but an unexpected link binds the two women together, and both are now in terrible danger.

Lesley Kara (left) specialises in creating tension between ordinary people in humdrum surroundings – in other words, normal circumstances experienced by the vast majority of us. I reviewed her excellent debut novel The Rumour, and her new book is centred around – as the name suggests – a murder that took place above Scarlett’s flat. The victim was her aunt, and as Scarlett tries to live as normal a life as possible with such a terrible event – almost literally – hanging over her head, it is up to her to make the funeral arrangements for her relative. As she does so, she meets Dee, the funeral director. Dee has problems of her own, but an unexpected link binds the two women together, and both are now in terrible danger.  For the uninitiated, Merrily Watkins is a single mum, and vicar of a village in Herefordshire. She also serves as Diocesan Deliverance Consultant – aka an exorcist. The series began in 1998 with The Wine of Angels, and seemed to have terminated rather abruptly with All of a Winter’s Night in 2017. A new book titled For The Hell of It was billed to come out in 2020, but this seems to have been reimagined as The Fever of the World. Here, Merrily becomes involved in a murder investigation led by local copper David Vaynor who, in a previous life, was an expert in the poetry of William Wordsworth. Aficionados of the work of Wordsworth may well recognise the provenance of the book’s title, taken from the poem composed on the banks of the River Wye near Tintern Abbey:

For the uninitiated, Merrily Watkins is a single mum, and vicar of a village in Herefordshire. She also serves as Diocesan Deliverance Consultant – aka an exorcist. The series began in 1998 with The Wine of Angels, and seemed to have terminated rather abruptly with All of a Winter’s Night in 2017. A new book titled For The Hell of It was billed to come out in 2020, but this seems to have been reimagined as The Fever of the World. Here, Merrily becomes involved in a murder investigation led by local copper David Vaynor who, in a previous life, was an expert in the poetry of William Wordsworth. Aficionados of the work of Wordsworth may well recognise the provenance of the book’s title, taken from the poem composed on the banks of the River Wye near Tintern Abbey: