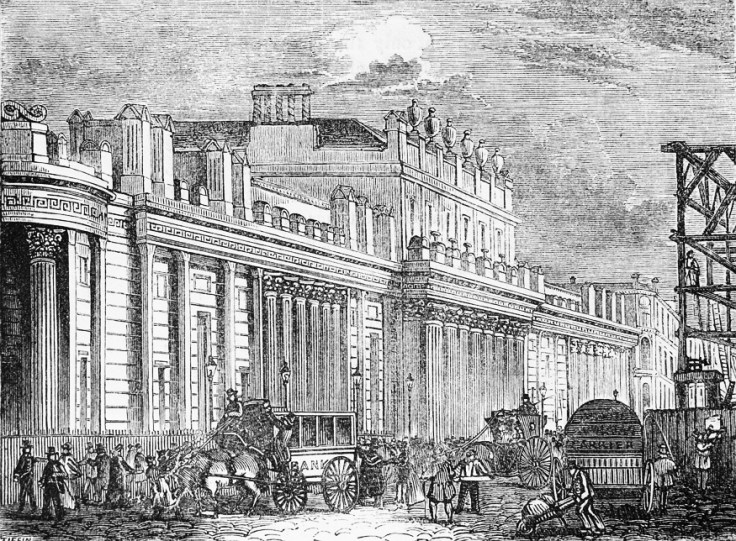

AUTHOR NICHOLAS BOOTH continues his amazing tale of a gang of Victorian fraudsters who made the Bank of England look very, very foolish.

Part one of the saga is HERE

Still, even under lock and key in Spanish-ruled Havana, Austin Bidwell (right) thought he would get away with it. His absence from London at the most crucial juncture meant, in his estimation, that any evidence against him was hearsay. And, until my research, most of the accounts about the “great forgery” can be classed as the same. All the thieves of Threadneedle Street were inveterate liars and fantasists who shrouded their endeavours in mystery, but even Pinkerton was prone to self-aggrandisement.

Still, even under lock and key in Spanish-ruled Havana, Austin Bidwell (right) thought he would get away with it. His absence from London at the most crucial juncture meant, in his estimation, that any evidence against him was hearsay. And, until my research, most of the accounts about the “great forgery” can be classed as the same. All the thieves of Threadneedle Street were inveterate liars and fantasists who shrouded their endeavours in mystery, but even Pinkerton was prone to self-aggrandisement.

For example, in Austin’s later version of events, Willie Pinkerton had suddenly appeared in Cuba, apologised for spoiling a dinner party and announced he had a warrant for the fugitive’s arrest. When offered a glass of wine by the urbane forger, the detective had supposedly agreed, adding: “I never drink anything but Clicquot” and then Austin had pulled a gun, shot a policeman and tried to escape. In Pinkerton’s later recollection, the detective claimed he had “passed the very ship that had Bidwell on board while rounding him into port” and arrested him there and then. But as his own files show, the detective didn’t actually arrive for another two weeks, by which time Austin Bidwell was in custody. Nor was anyone shot. In fact, Pinkerton really got his man by sowing doubts in the mind of his wife.

Jeannie Bidwell had never known what her husband had really been up to. The first she even learned of the great fraud was when American newspapers reported it. (It was to be headline news for weeks on both sides of the Atlantic.) “Who had the audacity to rob the Bank of England!” she exclaimed. “He ought to have a whipping!” Austin wisely said nothing. But when gossipy American expats asked who was behind it all, he smilingly conjectured that it was “some clever young scamp, with plenty of money of his own, who did it for the excitement of the thing and from a wish to take a rise out of John Bull”. Which, from such an incorrigible liar, wasn’t too far from the truth for once.

However, by the time Pinkerton met Jeannie in April 1873, her world had fallen apart – as we can see from hitherto unknown letters to her mother. “One evening we were romping, Austin and I, and a knock came very loudly,” she wrote. After opening the door, “in walked the [local] police”. By the time Pinkerton arrived, and it was left to the detective to explain Austin’s actions – and indeed to embellish them, with tales of bigamy and what Jeannie called “all those other women”.

When Jeannie reproached her husband with this in a letter to his cell, he replied: “Those children of mine and the wife that the detective spoke to you of are my brother’s property. You must allow yourself, dear, that if I was a father at twelve years of age, I began very young.”

Still, Pinkerton became a canny go-between, reading and copying their correspondence – which also revealed beyond any doubt that members of the New York Police Department were involved with the gang. Pinkerton himself promptly arrested a suspected New York “swell thief” who had come as an emissary from the underworld to spring their ally.

What then played out was a game of cat and mouse – and not just in Cuba. George Bidwell  (left)– a baleful influence on his brother – had what he later termed “a series of the most extraordinary adventures” across Ireland and Scotland (“a hell’s chase, and no mistake”) before lapping up the attention at his subsequent trial. Another of the gang, George Macdonnell (“a debonair scoundrel”) made it across the Atlantic where he handed his spoils to corrupt NYPD detectives. “I’m clean,” he taunted Pinkerton’s operatives. “You can’t prove anything on me.”

(left)– a baleful influence on his brother – had what he later termed “a series of the most extraordinary adventures” across Ireland and Scotland (“a hell’s chase, and no mistake”) before lapping up the attention at his subsequent trial. Another of the gang, George Macdonnell (“a debonair scoundrel”) made it across the Atlantic where he handed his spoils to corrupt NYPD detectives. “I’m clean,” he taunted Pinkerton’s operatives. “You can’t prove anything on me.”

But Austin was dealing with more than just Pinkerton. As his nemesis – to quote the Bank’s solicitors, Freshfields – an “adversary whom the forgers had least of all suspected had sprung up: that is to say, [his] mother-in-law”.

Though she had reluctantly attended the Bidwells’ wedding, Mrs Devereux actually fainted during the ceremony and was certain that her son-in-law was up to no good. So when the police alerted the London press that Mr Warren/Horton had been “accompanied by a young woman 18 to 20 years, looks younger with golden hair”, Mrs Devereux knew perfectly well who that was and went to the nearest solicitors. Before long, a letter from Jeannie to her mother with a St Thomas stamp arrived, the search zeroed in on the Caribbean, and Pinkerton learned of a glamorous young couple who had recently arrived in Havana. An “all points” bulletin, issued on the evidence of Jeannie’s mother, led to Austin being put under guard. By the time he arrived in Cuba, Pinkerton was certain the authorities had been bribed to look the other way. Austin Bidwell had been allowed to spend the first night of his detention in his luxurious hotel, the Telegrafo. And when the police moved him to barracks, they failed to search him, provided him with gourmet meals and let him receive visitors. Pinkerton knew well what his quarry was capable of. Indeed, over Easter, Austin escaped, and he was only apprehended after crossing swords with a Cuban captain, some 50 miles from Havana.

In Austin Bidwell’s version of the escape, he had made a dramatic leap from a balcony into the crowded street below. As Pinkerton determined, the fall would have killed him, and he had simply bribed his warders. But then, money – and the want of it – was at the heart of Bidwell’s story. And even in what the Lord Chief Justice later described as “the most remarkable trial that ever occurred in the annals of England”, scant attention was paid to the human cost, certainly by the criminals. Both Bidwell brothers were sentenced to life with penal servitude (though they were released in the 1890s). And George later noted they had left behind “no ruined widows and orphans to linger out the remainder of their blighted lives in poverty”. Which was not quite true.

The Bidwell gang stand trial in London

Jeannie endured a terrifying episode on the Bidwells’ return to London in May. (Austin was consigned to Newgate jail; she went back to her mother.) Having become pregnant in Cuba, one evening in September she went into labour. A little girl briefly came into the world and moments later passed away, while Jeannie herself nearly died. The dead infant was wrapped in a night shirt and dispatched by carriage to an undertaker, chosen at random from a directory. This was technically illegal, as she had not obtained a death certificate, and the police soon traced the unfortunate family.

Two weeks later, Jeannie Bidwell was arrested and taken to Bow Street Magistrates Court. Because she was so young and ill, and had already suffered so much, there was a great deal of sympathy. Jeannie’s mother – “a well dressed woman of respectable appearance” in one report – and a servant were also placed in the dock. All three were bailed but at the start of October, their cases were dismissed.

Wiser and cooler heads had prevailed. For once, the Victorian legal system was compassionate and realised that the poor girl had suffered enough. While Austin Bidwell found it amusing that he had embarrassed the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street (above) by holding “up to the laughter of the whole world its red-tape idiotic management”, poor Jeannie Bidwell was sent to a workhouse in nearby St Giles, becoming the one indisputable victim of the greatest ever forgery in history.

The article first appeared in The Independent in 2015,

and is used with the permission of the author

For a closer look at Nicholas Booth’s comprehensive account of this remarkable case,

FOLLOW THIS LINK

TO THE CASUAL OBSERVER Wisbech appears to be a fairly dull market town, a bit down on its luck, but otherwise unremarkable. It has, however, over the last decade or so, built for itself an unenviable record of murders. In this podcast, we take a closer look.

TO THE CASUAL OBSERVER Wisbech appears to be a fairly dull market town, a bit down on its luck, but otherwise unremarkable. It has, however, over the last decade or so, built for itself an unenviable record of murders. In this podcast, we take a closer look. A FREE LUNCH? As in ‘no such thing as’? Normally, the old adage is pretty true, but it seems that you can feast your mind. if not your tummy, with a genuine free offer from author Wendy Cartmell (left). She is best known for her series of Sgt. Major Crane stories, featuring the gritty Military Policeman, but she has a more recent heroine, Emma Harrison. She is an Assistant Governor of Reading Young Offenders’ Institution, and while her charges are callow youths, they are well versed in all kinds of villainy, and the broken lives which have pitched them into the Institution have made some of them very damaged indeed.

A FREE LUNCH? As in ‘no such thing as’? Normally, the old adage is pretty true, but it seems that you can feast your mind. if not your tummy, with a genuine free offer from author Wendy Cartmell (left). She is best known for her series of Sgt. Major Crane stories, featuring the gritty Military Policeman, but she has a more recent heroine, Emma Harrison. She is an Assistant Governor of Reading Young Offenders’ Institution, and while her charges are callow youths, they are well versed in all kinds of villainy, and the broken lives which have pitched them into the Institution have made some of them very damaged indeed.

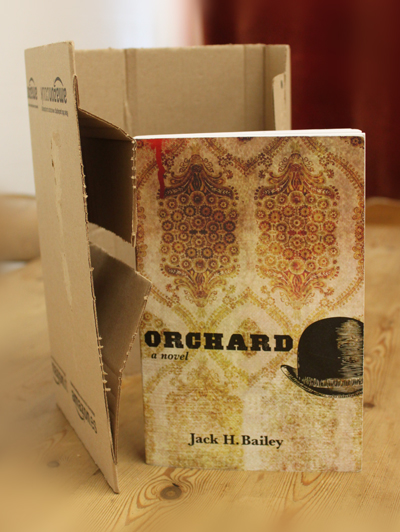

KINDLE ROUNDUP, JULY 25th 2016. It has to be said, for all that it’s a wonderful invention, and has revolutionised reading, The Kindle (other devices are available!) can provide a pitfall for the book reviewer. While a physical To Be Read pile is ever visible, and sits in the corner looking at you in an accusing fashion, the equivalent stack of books on the digital reader quietly goes away when the power is turned off. So, with apologies to the writers and publishers who have trusted me with their offspring, here is my first, but belated, look at some great titles.

KINDLE ROUNDUP, JULY 25th 2016. It has to be said, for all that it’s a wonderful invention, and has revolutionised reading, The Kindle (other devices are available!) can provide a pitfall for the book reviewer. While a physical To Be Read pile is ever visible, and sits in the corner looking at you in an accusing fashion, the equivalent stack of books on the digital reader quietly goes away when the power is turned off. So, with apologies to the writers and publishers who have trusted me with their offspring, here is my first, but belated, look at some great titles. Mercedes Marie by Fusty Luggs

Mercedes Marie by Fusty Luggs No Accident by Robert Crouch

No Accident by Robert Crouch Falling Suns by J.A. Corrigan

Falling Suns by J.A. Corrigan The Woman In The Woods by Louise Mullins

The Woman In The Woods by Louise Mullins Unquiet Souls by Liz Mistry

Unquiet Souls by Liz Mistry

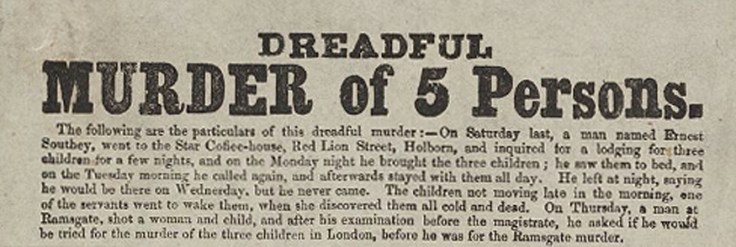

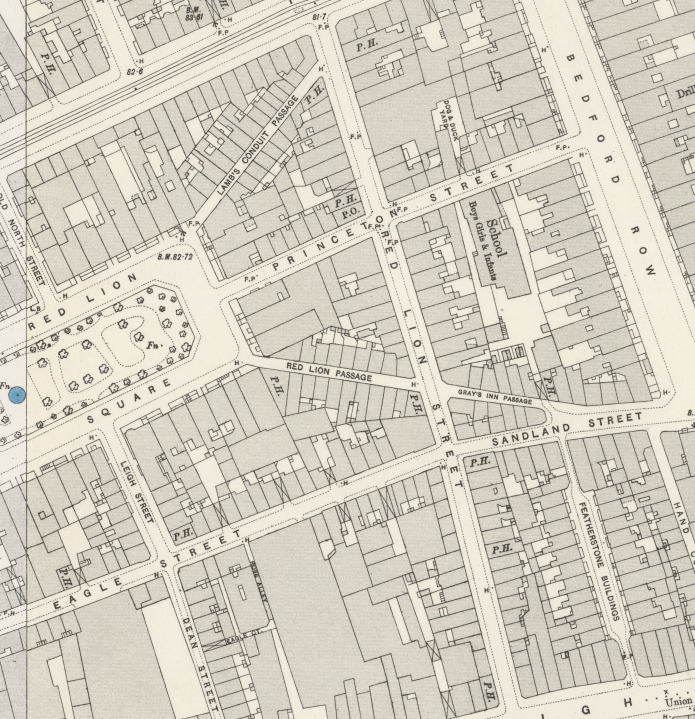

“On the 9th of August last I was requested by Dr. ROBERTS, of Lamb’s Conduit-street to visit Star’s Hotel, where, as he informed me, three children were supposed to have been murdered, and that in case of so serious a nature he deemed it advisable to have a second opinion. On the third floor, in the front room, No. 6 of the above-named hotel I saw two boys lying on their backs in bed quite dead. The younger of the two, ALEXANDER WHITE, aged eight was near the back, the elder, THOMAS WILLIAM WHITE, aged nine years, toward the front part of the bed. The bodies of both were cold and stiff, and although their countenances wore the placidity of slumber they nevertheless bore the pallor of death. The eyes were half open; the pupils semi-dilated. On turning down the bedclothes both bodies presented a mottled appearance, from the extreme lividity of some parts, the deadly pallor of others. The attitude of the youngest child was that of a comfortable repose. The head slightly inclined to the left side. The hands were folded upon the abdomen. The legs gently crossed. The fingers of the right hand still retained within them a penny-piece, which fell from their stiffened grasp while the body was being turned upon its side, with the view of detecting marks of violence.”

“On the 9th of August last I was requested by Dr. ROBERTS, of Lamb’s Conduit-street to visit Star’s Hotel, where, as he informed me, three children were supposed to have been murdered, and that in case of so serious a nature he deemed it advisable to have a second opinion. On the third floor, in the front room, No. 6 of the above-named hotel I saw two boys lying on their backs in bed quite dead. The younger of the two, ALEXANDER WHITE, aged eight was near the back, the elder, THOMAS WILLIAM WHITE, aged nine years, toward the front part of the bed. The bodies of both were cold and stiff, and although their countenances wore the placidity of slumber they nevertheless bore the pallor of death. The eyes were half open; the pupils semi-dilated. On turning down the bedclothes both bodies presented a mottled appearance, from the extreme lividity of some parts, the deadly pallor of others. The attitude of the youngest child was that of a comfortable repose. The head slightly inclined to the left side. The hands were folded upon the abdomen. The legs gently crossed. The fingers of the right hand still retained within them a penny-piece, which fell from their stiffened grasp while the body was being turned upon its side, with the view of detecting marks of violence.” “In the back bedroom, No. 8, of the same floor lay the dead body of a somewhat emaciated but handsomely featured boy, HENRY WILLIAM WHITE, aged ten years. The attitude and complexion of this child closely resembled that of his brothers. His expression was calm, the eyelids were closed, the pupils were natural, the face was deadly pale. A small quantity of fluid had flowed from the mouth on to the collar of his shirt, and that part of the left cheek in contact with it was mottled red and purple. The legs and toes were slightly bent the hands partially closed, the nails and finger tips intensely livid. A spot of feculent matter soiled the sheet. The rigidity of death was well marked in every l imb, and livid discolorations in all the depending parts of the body. No marks of violence were observable, but a slight odor was perceptible about the mouth. The whole chamber had a peculiar ethereal smell.”

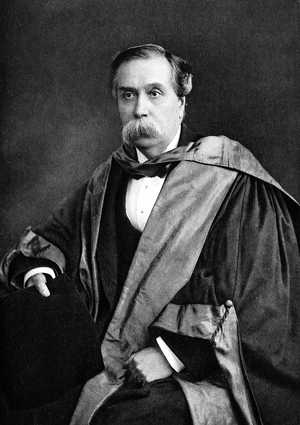

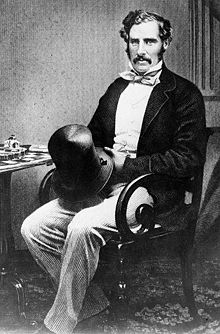

“In the back bedroom, No. 8, of the same floor lay the dead body of a somewhat emaciated but handsomely featured boy, HENRY WILLIAM WHITE, aged ten years. The attitude and complexion of this child closely resembled that of his brothers. His expression was calm, the eyelids were closed, the pupils were natural, the face was deadly pale. A small quantity of fluid had flowed from the mouth on to the collar of his shirt, and that part of the left cheek in contact with it was mottled red and purple. The legs and toes were slightly bent the hands partially closed, the nails and finger tips intensely livid. A spot of feculent matter soiled the sheet. The rigidity of death was well marked in every l imb, and livid discolorations in all the depending parts of the body. No marks of violence were observable, but a slight odor was perceptible about the mouth. The whole chamber had a peculiar ethereal smell.” The Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (left), announced a £100 reward for the apprehension of Southey. It was to prove unnecessary. Having poisoned the three boys, the fugitive, who obviously subscribed to the old adage about sheep and lambs, had traveled down to the Kent seaside town of Ramsgate where, it transpired, his real wife and daughter lived. Having met them, and pleaded for their forgiveness for his long absence and neglect, he then shot them both dead with a pistol. He was caught red-handed, and gave himself up without a struggle.

The Home Secretary, Sir George Grey (left), announced a £100 reward for the apprehension of Southey. It was to prove unnecessary. Having poisoned the three boys, the fugitive, who obviously subscribed to the old adage about sheep and lambs, had traveled down to the Kent seaside town of Ramsgate where, it transpired, his real wife and daughter lived. Having met them, and pleaded for their forgiveness for his long absence and neglect, he then shot them both dead with a pistol. He was caught red-handed, and gave himself up without a struggle. charged with murder, for criminal murders as well in the truest, strongest sense of the charge. I deny and repudiate the charge, and charge it back on many who have by their gross and criminal neglect brought about this sad and fearful crisis. I charge back the guilt of these crimes on those high dignitaries of the State, the Church, and justice who have turned a deaf ear to my heartbroken appeals, who have refused me fellow help in all my frenzied efforts, my exhausted struggles; who have impiously denied the sacredness of human life, the mutual dependence of man, and the fundamental and sacred principles on which our social system is based. Foremost among these I charge the Hon. D. Lord Palmerston, the Attorney General, Sir George Grey, the Hon. Mr. Gladstone, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ebury, Lord Townshend, Lord Elcho, Lord Brougham, Sir E. B Lytton, Mr Disraeli, Sir J. Packington, Earl Derby, Lord Stanley, Mr Crossley, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. I Under all the terrible run of my life I have done for the best.”

charged with murder, for criminal murders as well in the truest, strongest sense of the charge. I deny and repudiate the charge, and charge it back on many who have by their gross and criminal neglect brought about this sad and fearful crisis. I charge back the guilt of these crimes on those high dignitaries of the State, the Church, and justice who have turned a deaf ear to my heartbroken appeals, who have refused me fellow help in all my frenzied efforts, my exhausted struggles; who have impiously denied the sacredness of human life, the mutual dependence of man, and the fundamental and sacred principles on which our social system is based. Foremost among these I charge the Hon. D. Lord Palmerston, the Attorney General, Sir George Grey, the Hon. Mr. Gladstone, the Earl of Shaftesbury, Lord Ebury, Lord Townshend, Lord Elcho, Lord Brougham, Sir E. B Lytton, Mr Disraeli, Sir J. Packington, Earl Derby, Lord Stanley, Mr Crossley, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells. I Under all the terrible run of my life I have done for the best.” Whether the wretched man was exhibiting an early version of what we would come to know as The Blackadder Defence – wearing underpants on the head and sticking knitting needles up the nostrils, in the hope that he would be considered totally mad – we shall never know. Forward’s lawyer half-heartedly went for a plea of insanity, but his efforts were ignored.

Whether the wretched man was exhibiting an early version of what we would come to know as The Blackadder Defence – wearing underpants on the head and sticking knitting needles up the nostrils, in the hope that he would be considered totally mad – we shall never know. Forward’s lawyer half-heartedly went for a plea of insanity, but his efforts were ignored.

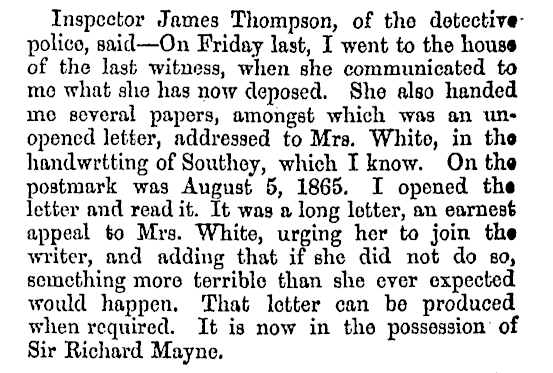

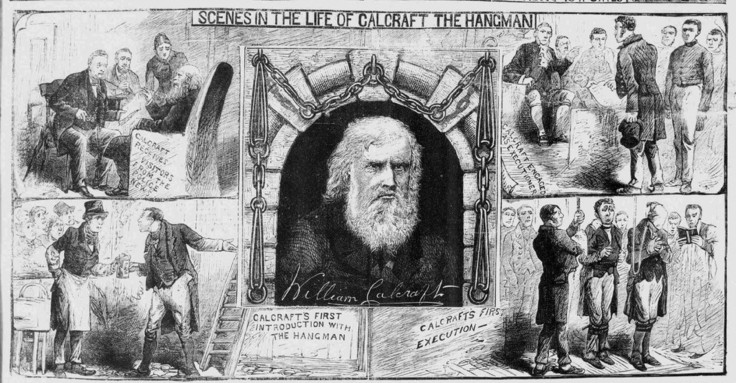

Arriving at the Gaol just before midday they immediately went to the cell where Forward was held. The executioner was Calcraft who acted as executioner at Stafford and in the “Midland Counties”. The prisoner asked for permission to speak and “exclaimed in an audible voice”, ” I desire to say in the presence of you who are now assembled, and in the presence of Almighty God, into whose immediate presence I am now about to depart, that I die trusting only to the merits of the God-man Jesus Christ”.

Arriving at the Gaol just before midday they immediately went to the cell where Forward was held. The executioner was Calcraft who acted as executioner at Stafford and in the “Midland Counties”. The prisoner asked for permission to speak and “exclaimed in an audible voice”, ” I desire to say in the presence of you who are now assembled, and in the presence of Almighty God, into whose immediate presence I am now about to depart, that I die trusting only to the merits of the God-man Jesus Christ”.

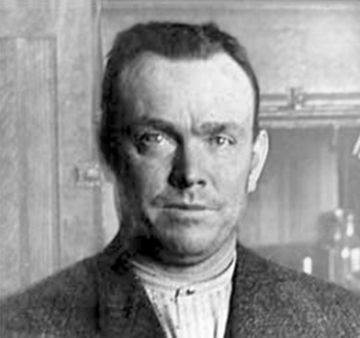

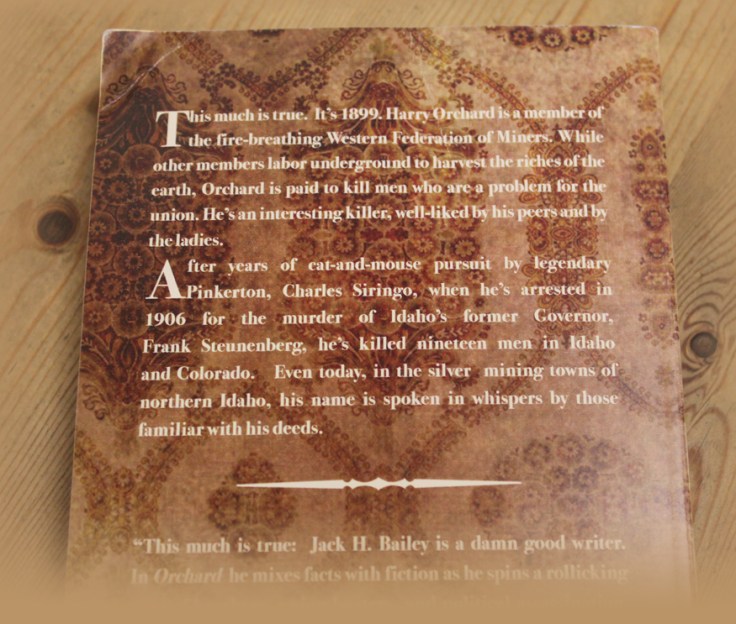

Orchard (right) had his mandatory death sentence commuted and he died in the state penitentiary in Boise, Idaho, on April 13, 1954, aged 88, over 48 years after his arrest. Jack Bailey’s novel is a fictionalised account of these momentous events, and will be available on

Orchard (right) had his mandatory death sentence commuted and he died in the state penitentiary in Boise, Idaho, on April 13, 1954, aged 88, over 48 years after his arrest. Jack Bailey’s novel is a fictionalised account of these momentous events, and will be available on

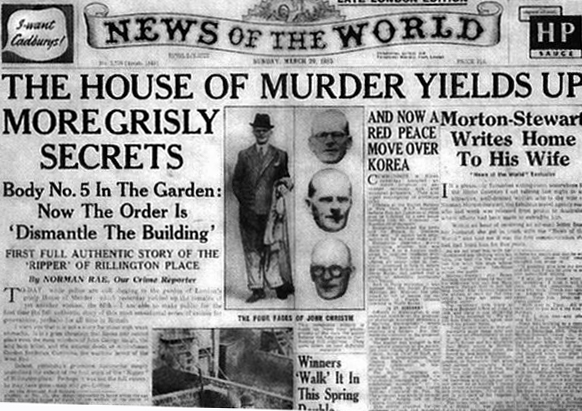

John Reginald Halliday Christie (left) moved to London in the 1920s, and developed into a career criminal, albeit of a petty sort. He had married Ethel Simpson in 1928, but they became estranged. They were reconciled, and set up home in a threadbare flat at 10 Rillington Place, Ladbroke Grove. It seems that Christie ticked a depressingly recurrent box on the checklist of serial killers. He was impotent under normal sexual circumstances, but seemed able to perform, after a fashion, with prostitutes.

John Reginald Halliday Christie (left) moved to London in the 1920s, and developed into a career criminal, albeit of a petty sort. He had married Ethel Simpson in 1928, but they became estranged. They were reconciled, and set up home in a threadbare flat at 10 Rillington Place, Ladbroke Grove. It seems that Christie ticked a depressingly recurrent box on the checklist of serial killers. He was impotent under normal sexual circumstances, but seemed able to perform, after a fashion, with prostitutes.