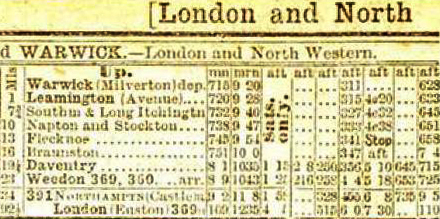

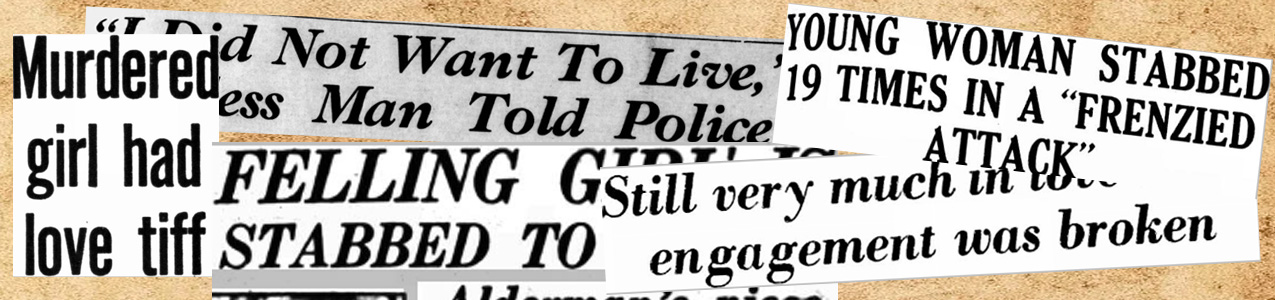

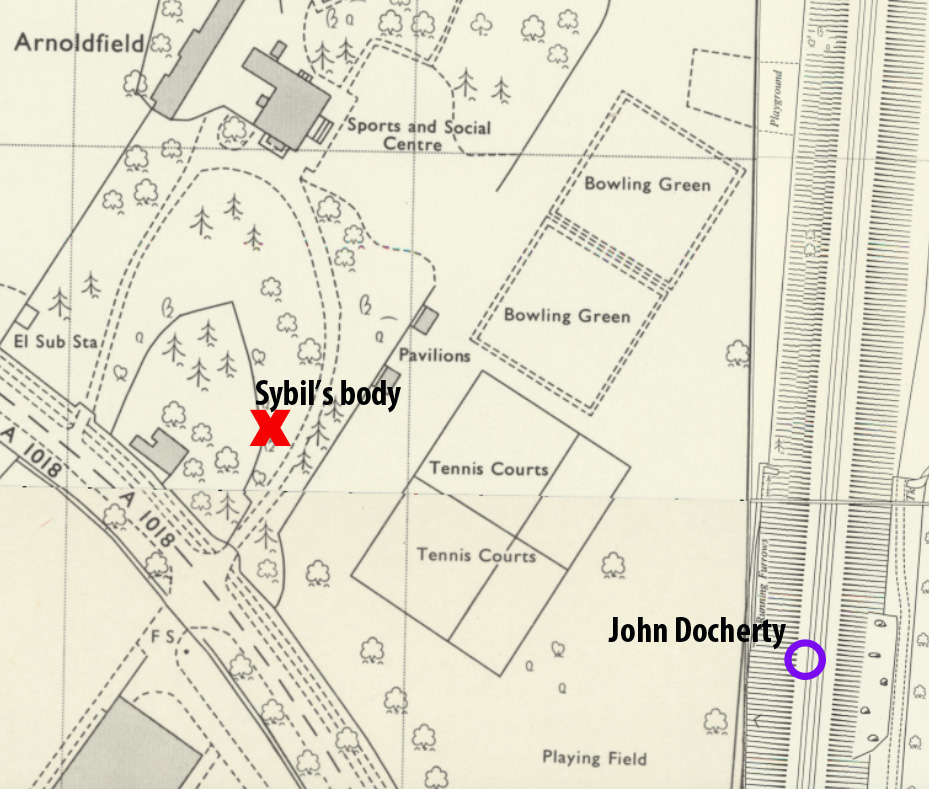

SO FAR: 10th August, 1954. Just after 11.00 am. In the drive leading up to the former mansion known as Arden Field just outside Grantham, the body of 24 year-old Sybil Hoy was found. She had been brutally murdered. Her body was taken away to the mortuary, and police began searching for the weapon. Just a few hundred yards away, across the Kings School playing fields, was the railway embankment that carried the London to Edinburgh main line. A railway lengthman (an employee responsible for walking a particular stretch of line checking for problems) had just climbed the embankments, and stood back as the London to Edinburgh service known as The Elizabethan Express thundered past.

SO FAR: 10th August, 1954. Just after 11.00 am. In the drive leading up to the former mansion known as Arden Field just outside Grantham, the body of 24 year-old Sybil Hoy was found. She had been brutally murdered. Her body was taken away to the mortuary, and police began searching for the weapon. Just a few hundred yards away, across the Kings School playing fields, was the railway embankment that carried the London to Edinburgh main line. A railway lengthman (an employee responsible for walking a particular stretch of line checking for problems) had just climbed the embankments, and stood back as the London to Edinburgh service known as The Elizabethan Express thundered past.

What he saw as the train clattered into the distance was utterly shocking. A man sat upright on the track, and just a few yards away, on the sleepers were the man’s severed legs. The man was conscious, and able to talk. An ambulance was summoned, and he was carried down the bank and rushed to hospital. The man was John Docherty, Sybil Hoy’s former fiancée.

Docherty, minus his legs, received further corrective surgery to the amputations delivered by the LNER locomotive, but was charged with murder, by a police office sitting at his bedside. He was conducted into a succession of magistrate hearings and eventually sent to be tried at Lincoln Assizes. It was the briefest of hearings, and he was sentenced to death.

After her body had been probed and prodded by investigators, it was eventually returned to her mother and father. God, or whoever controls the heavens, was not best pleased, because a violent storm rained down on the many mourners at the Victorian Christ Church in Felling

After her body had been probed and prodded by investigators, it was eventually returned to her mother and father. God, or whoever controls the heavens, was not best pleased, because a violent storm rained down on the many mourners at the Victorian Christ Church in Felling

In the long history of newspapers reporting on murders and executions, there can seldom have been a bigger gift to headline writers. The five words ‘Legless Man Sentenced To Hang’ appeared over and over again in newspapers, both regional and national. For the Home Secretary, Gwilym Lloyd-George, himself an MP for Newcastle, the impending execution posed unique practical problems. Docherty literally could not walk to the execution chamber. He would have to be taken there in his wheelchair, and Henry Pierrepoint (or whichever executioner was appointed to the job) would have to oversee the grotesque scene of a man placed on the trapdoor, presumably sitting on his backside, hands pinioned (as was customary) and thus unable to maintain his balance. Almost inevitably, given the bizarre circumstances, the execution was called off. What became of the reprieved killer of Sybil Hoy is unclear. For citizen researchers, access to prison records via genealogy sites ends in 1951, so it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that Docherty, born in 1926, could have been released and reached old age.

Because Docherty pleaded guilty, his state of mind and mental health was never raised in court. These days, we have too many examples of mentally ill people being free in the community to murder and maim. The Nottingham triple killer, Valdo Calocane is just one example. In Docherty’s case, his mindset was so febrile that within the space of sixty minutes or so, he inflicted nineteen ferocious knife wounds on his former fiancée, and then ran a few hundred yards to the main railway line, climbed the embankment and put himself in the path of an express train. I use those two words advisedly. People who commit suicide by train usually put the matter beyond doubt by throwing themselves bodily in front of the oncoming train. Is it possible that Docherty calculated that by just putting his legs on the line he would avoid fatal injury? We have no way of knowing. If it was a gamble, it paid off, because he evaded a date with the hangman. I have to say that if his actions were calculated, then he was an extremely devious individual.

To use a cricketing term, the Dr Temperance Brennan book series by Kathy Reichs (left) is 24 not out, and still looking good. The series featuring the forensic anthropologist began with Déjà Dead in 1997. For anyone new to the novels, I’ll just direct you

To use a cricketing term, the Dr Temperance Brennan book series by Kathy Reichs (left) is 24 not out, and still looking good. The series featuring the forensic anthropologist began with Déjà Dead in 1997. For anyone new to the novels, I’ll just direct you

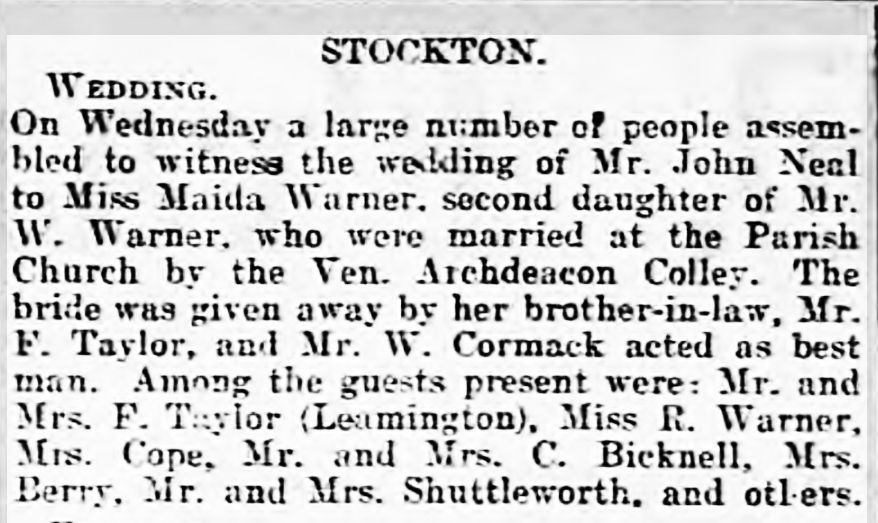

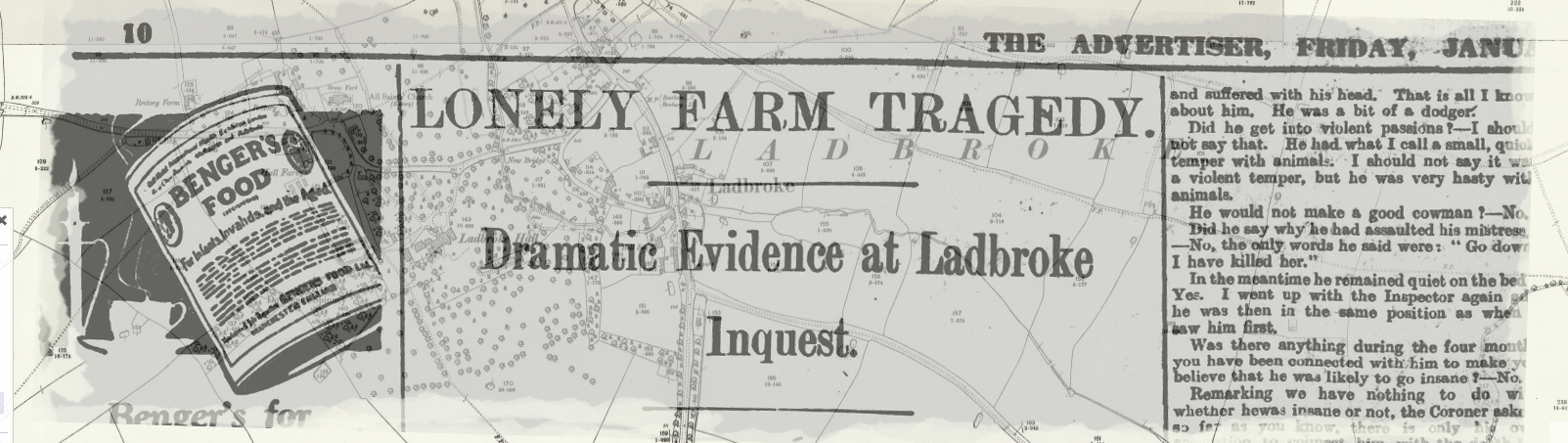

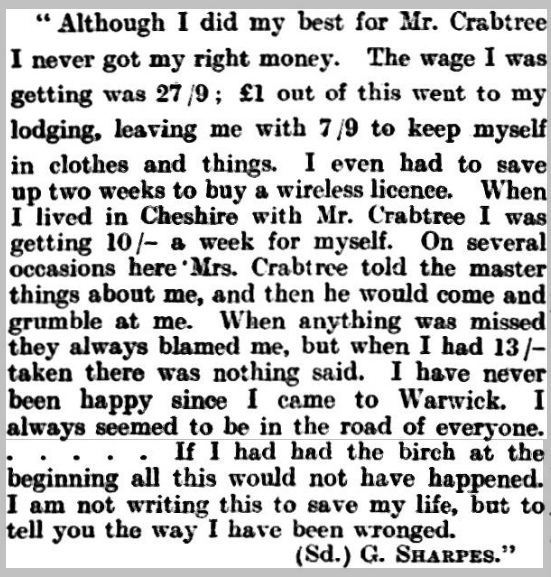

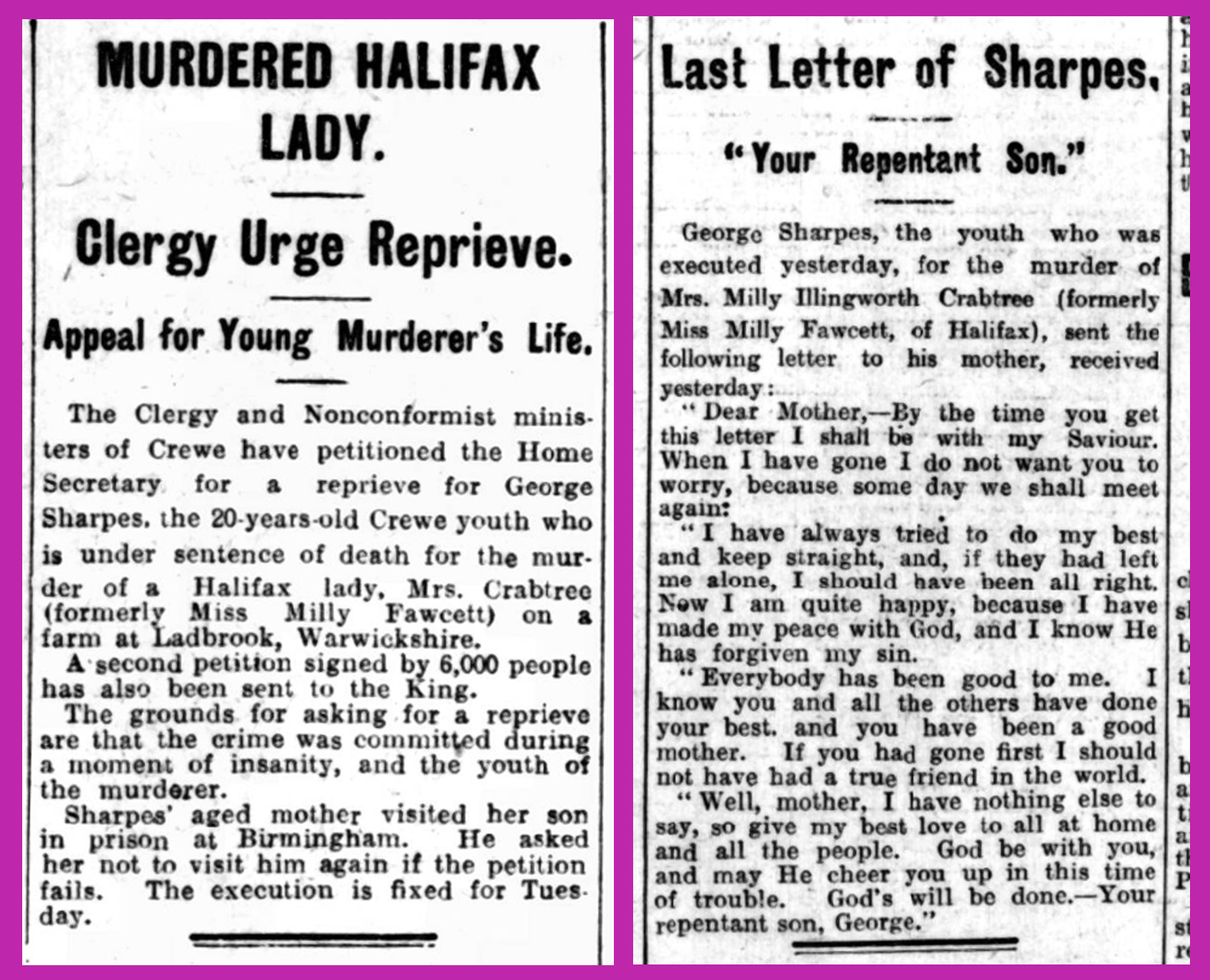

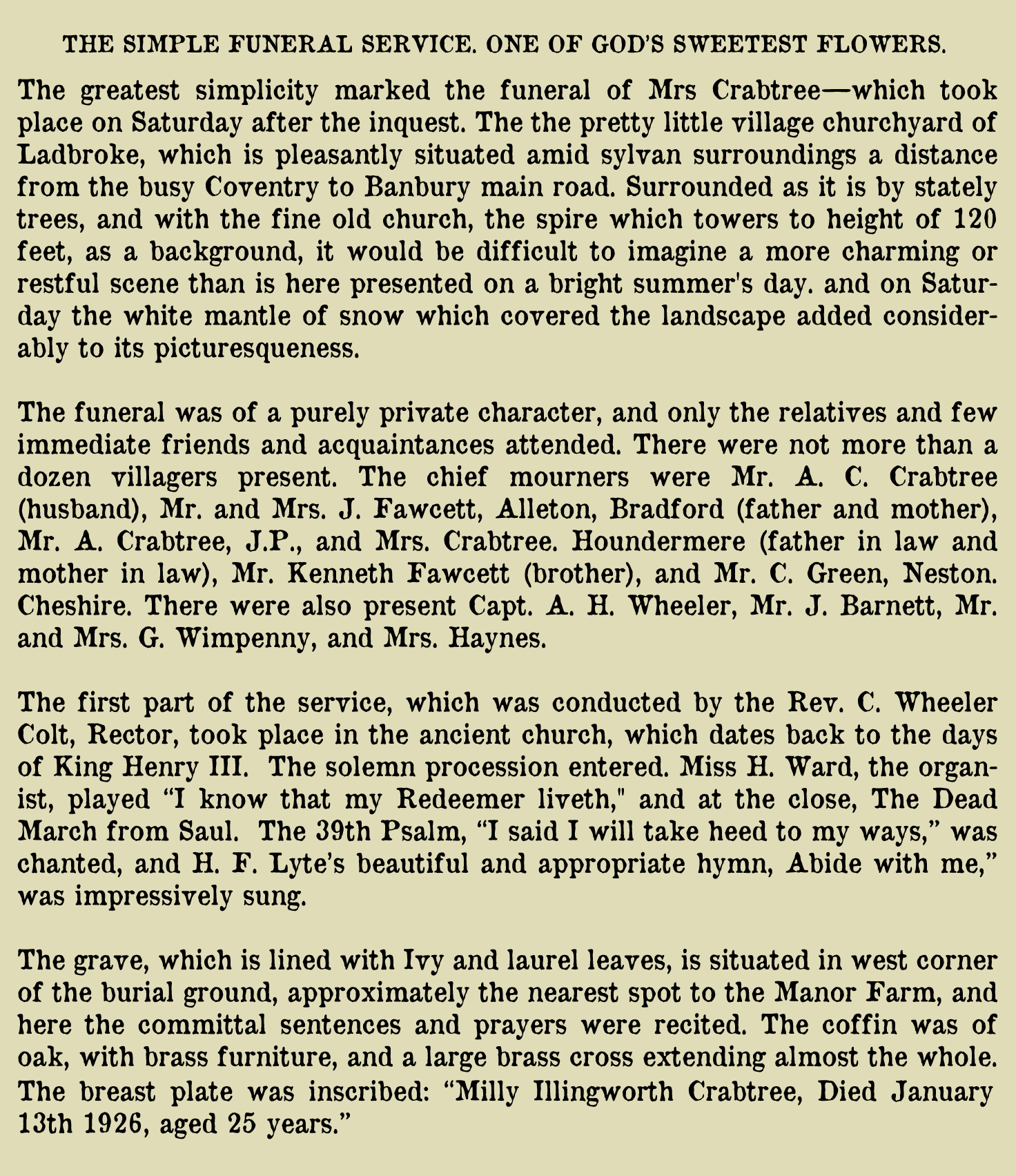

SO FAR – On January 13th 1926, Milly Crabtree, 25 year-old wife of Cecl Crabtree, is found battered to death at their home, Manor Farm in Ladbroke. 19 year-old George Sharpes is arrested for her murder. As is the way with these, things, the wheels of justice turn very slowly, and it was February before Sharpes came to face magistrates in Southam. The courtroom, normally used as a cinema (pictured above), was packed, and the onlookers were spellbound as a confession from George Sharpes was read to the court.

SO FAR – On January 13th 1926, Milly Crabtree, 25 year-old wife of Cecl Crabtree, is found battered to death at their home, Manor Farm in Ladbroke. 19 year-old George Sharpes is arrested for her murder. As is the way with these, things, the wheels of justice turn very slowly, and it was February before Sharpes came to face magistrates in Southam. The courtroom, normally used as a cinema (pictured above), was packed, and the onlookers were spellbound as a confession from George Sharpes was read to the court.

The magistrates wasted little time in stating that George Sharpes had a serious case to answer, and the case was moved on to be examined at the March Assizes in Warwick. The case was presided over by Mr Justice Shearman. The only possible line for the defence to take was that Sharpes was insane at the time at the time he committed the murder, and Sharpes’s mother was produced to state that her son had suffered an unfortunate childhood. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, however. Rejecting the claims that George Sharpes was insane, the judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death. The execution was fixed for April and, as was almost always the case, a petition was set up to ask for clemency. The case was taken to appeal, in front of Lord Chief Justice Avory, who was perhaps not the most welcome choice for Sharpes’s defence team. Avory, a notorious “hanging judge”, had been memorably described:

The magistrates wasted little time in stating that George Sharpes had a serious case to answer, and the case was moved on to be examined at the March Assizes in Warwick. The case was presided over by Mr Justice Shearman. The only possible line for the defence to take was that Sharpes was insane at the time at the time he committed the murder, and Sharpes’s mother was produced to state that her son had suffered an unfortunate childhood. Her pleas fell on deaf ears, however. Rejecting the claims that George Sharpes was insane, the judge donned the black cap and sentenced him to death. The execution was fixed for April and, as was almost always the case, a petition was set up to ask for clemency. The case was taken to appeal, in front of Lord Chief Justice Avory, who was perhaps not the most welcome choice for Sharpes’s defence team. Avory, a notorious “hanging judge”, had been memorably described:

Manor Farm in Ladbroke dates back, according to the data on British Listed Buildings, to the mid 18th century. For architectural historians, it adds:

Manor Farm in Ladbroke dates back, according to the data on British Listed Buildings, to the mid 18th century. For architectural historians, it adds:

CLICK ON ANY TAG AND THE CONTENT

CLICK ON ANY TAG AND THE CONTENT