Something we do all too rarely on Fully Booked, mea culpa, is to feature articles and reviews by guest writers. I am delighted that an old mate of mine, Stuart Radmore (we go back to the then-down-at-heel Melbourne suburbs of Carlton and Parkville in the 1970s, where he was a law student and I was teaching art at Wesley College) has written this feature on a writer who, as an individual, never actually existed. Stuart’s knowledge of crime fiction is immense, and so I will let him take up the story.

Something we do all too rarely on Fully Booked, mea culpa, is to feature articles and reviews by guest writers. I am delighted that an old mate of mine, Stuart Radmore (we go back to the then-down-at-heel Melbourne suburbs of Carlton and Parkville in the 1970s, where he was a law student and I was teaching art at Wesley College) has written this feature on a writer who, as an individual, never actually existed. Stuart’s knowledge of crime fiction is immense, and so I will let him take up the story.

P.B Yuill was the transparent alias of Gordon Williams and Terry Venables, who in the early to mid 1970s wrote a number of novels together. Gordon Williams (1934-2017) and pictured below, started out as a straight novelist, but over time would turn his hand to almost anything literary – thrillers, SF screenplays, even ghosted footballer’s memoirs. Terry Venables (b. 1943) was at this time described as “top football star already worth over £150,000 in transfer fees”.

Their first joint outing (published under their own names) was They Used To Play On Grass (1971). Described, not incorrectly, on the paperback cover as “the greatest soccer novel ever”, it’s still an enjoyable read, with each man’s contribution being pretty obvious.

Their first joint outing (published under their own names) was They Used To Play On Grass (1971). Described, not incorrectly, on the paperback cover as “the greatest soccer novel ever”, it’s still an enjoyable read, with each man’s contribution being pretty obvious.

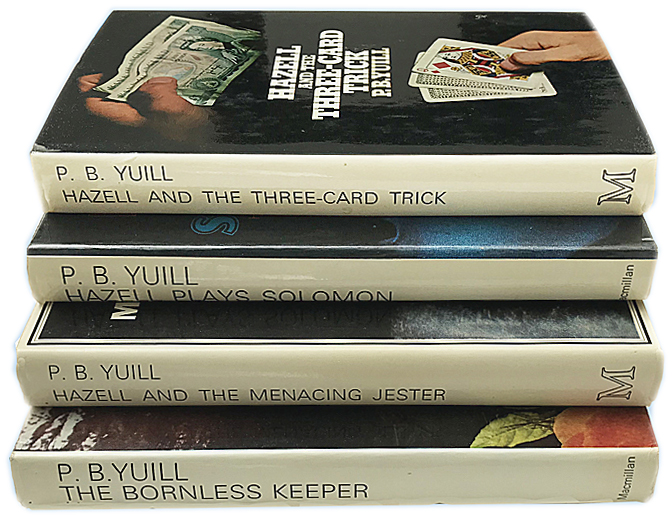

Next up was The Bornless Keeper (1974), published under the name of PB Yuill. A credible horror/thriller, set in modern times.

“Peacock Island lies just off the English south coast. But it could belong to an earlier century; its secret overgrown coverts, its strange historic legends are maintained and hidden by the rich old lady who lives there as a recluse.”.

If the tale now seems overfamiliar – the moody locals, the over-inquisitive visiting film crew, the one person who won’t be told not to go out alone – it’s partly because these elements, perhaps corny even then, have been over-used in too many slasher movies since. Although credited to P.B Yuill, the setting and theme of the novel reads as the work of Gordon Williams alone

Now to Hazell. There are three Hazell novels, published by Macmillan in 1974, ’75 and ’76 – Hazell Plays Solomon, Hazell and the Three Card Trick, and Hazell and the Menacing Jester.

The premise of the first novel is original; James Hazell, ex-copper and self-described “biggest bastard who ever pushed your bell button” is hired by a London woman, now wealthy and living in the US, to confirm her suspicion that her child was switched for another shortly after its birth in an East London maternity hospital. Clearly, there can be no happy ending to such enquiries, and the story leads to dark places and deep secrets.

The next two novels are a little lighter in tone, but still deal with the grittier side of London life. In Three Card Trick a man has apparently suicided by jumping in front of a Tube train. His widow doesn’t accept this – there is the insurance to consider – and hires Hazell to prove her right.

In Menacing Jester we are on slightly more familiar PI ground; a millionaire and his wife are apparently the victims of a practical joker. Or is there something more sinister behind it?

All three novels contain plenty of sex, violence and local colour – card sharps, clip joint hostesses, Soho drinking dens – and the authors were clearly familiar with the more picturesque aspects of the London underworld and portray these with energy and humour. Readers looking for evidence of the “casual racism/sexism/whatever” of the 1970s will not come away empty-handed.

The authors were keen to develop the Hazell character into a possible TV series, and the later two books seem to be written with this in mind. This duly came to pass, via Thames Television, and the first series was broadcast in 1978, starring Nicholas Ball as a youthful James Hazell. Gordon Williams, with Venables (right) and other writers, was responsible for a number of the episodes (including ‘Hazell Plays Solomon’), and it remains a very watchable series. The second, and final, series broadcast in 1979/80 was not so successful. The hardness was gone, Hazell and Inspector ‘Choc’ Minty had become something of a double act and, while not outright comedy, it came close at times. It’s not surprising to learn that Leon Griffiths, one of the second series screenwriters, went on to create and develop the very successful series Minder later that year.

The authors were keen to develop the Hazell character into a possible TV series, and the later two books seem to be written with this in mind. This duly came to pass, via Thames Television, and the first series was broadcast in 1978, starring Nicholas Ball as a youthful James Hazell. Gordon Williams, with Venables (right) and other writers, was responsible for a number of the episodes (including ‘Hazell Plays Solomon’), and it remains a very watchable series. The second, and final, series broadcast in 1979/80 was not so successful. The hardness was gone, Hazell and Inspector ‘Choc’ Minty had become something of a double act and, while not outright comedy, it came close at times. It’s not surprising to learn that Leon Griffiths, one of the second series screenwriters, went on to create and develop the very successful series Minder later that year.

And that was about it. But there was to be a last hurrah for Hazell in print. Two Hazell annuals, “based on the popular television series”, appeared in 1978 and 1979. The tales in these books are surprisingly tough, bearing in mind the intended teenage readership. Hazell’s adventures are told via short stories and comic strips, and include strong-ish violence, blackmail and other criminality. While the contribution of “P. B Yuill” was probably nil, the stories are true to the feel of the first series of the TV programme.

To conclude: English fictional private eyes are a rare breed, and fewer still can claim to have begun as a literary, rather than television, creation. Hazell is among the best of these. The three novels rightly remain in print, and are eminently readable.

There is a postscript. There was one last appearance of P.B Yuill. In early 1981 ‘Arena’, a BBC2 documentary series, devoted a programme to the attempts of Williams and Venables to write a new Hazell adventure – tentatively entitled ‘Hazell and the Floating Voter’ – and it featured such worthies as John Bindon and Michael Elphick playing the part of Hazell. It’s never been broadcast since, and while it was pleasing to see the authors discussing the character of Hazell, in retrospect the programme seems like an excuse for a few days’ drinking on licence-payers’ money.

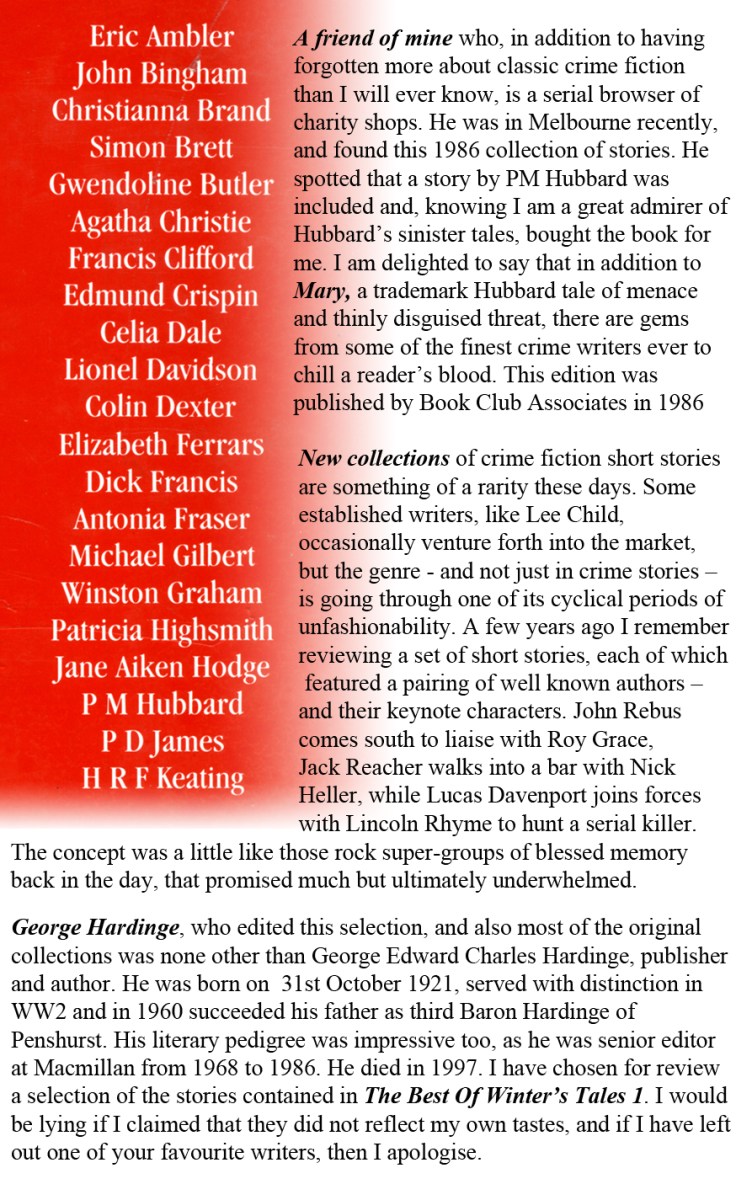

I have a close friend who keeps himself fit by walking London suburbs searching charity shops for rare – and sometimes valuable – crime novels. On one particular occasion he was spectacularly successful with a rare John le Carré first edition, but he is ever alert to particular fads and enthusiasms of mine. Since I “discovered” PM Hubbard, thanks to a tip-off from none other than

I have a close friend who keeps himself fit by walking London suburbs searching charity shops for rare – and sometimes valuable – crime novels. On one particular occasion he was spectacularly successful with a rare John le Carré first edition, but he is ever alert to particular fads and enthusiasms of mine. Since I “discovered” PM Hubbard, thanks to a tip-off from none other than  Seldom, however, can a treasure have been protected by two more menacing guardians in Aunt Elizabeth and her maid-of-all-work Coster. Remember Blind Pew, one of the more terrifying villains of literature? Remember Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and the decades that it was hidden from sight? With a freedom that simply would not escape the censor today, Hubbard (right) taps into our visceral fear of abnormality and disability. Hubbard has created two terrifying women and a dog which is makes Conan Doyles celebrated hound Best In Show. The dog first:

Seldom, however, can a treasure have been protected by two more menacing guardians in Aunt Elizabeth and her maid-of-all-work Coster. Remember Blind Pew, one of the more terrifying villains of literature? Remember Tod Browning’s Freaks (1932) and the decades that it was hidden from sight? With a freedom that simply would not escape the censor today, Hubbard (right) taps into our visceral fear of abnormality and disability. Hubbard has created two terrifying women and a dog which is makes Conan Doyles celebrated hound Best In Show. The dog first:

Mr Bulmer is a uniquely repulsive little man who manages a dry cleaning shop in Mayfair, and uses the opportunity of searching through the jackets and trouser pockets of wealthy individuals to service his own very profitable blackmail industry. His malignant little sideline has provided him with a regular income – and driven at least one of his victims to suicide. When he seizes upon what he sees as the opportunity of a lifetime, he is unaware that is about to be snared by his own hook. John Bingham, in addition to being a writer of distinction, was also a highly placed official in British Intelligence operations.

Mr Bulmer is a uniquely repulsive little man who manages a dry cleaning shop in Mayfair, and uses the opportunity of searching through the jackets and trouser pockets of wealthy individuals to service his own very profitable blackmail industry. His malignant little sideline has provided him with a regular income – and driven at least one of his victims to suicide. When he seizes upon what he sees as the opportunity of a lifetime, he is unaware that is about to be snared by his own hook. John Bingham, in addition to being a writer of distinction, was also a highly placed official in British Intelligence operations. Crispin, aka Robert Bruce Montgomery, is best known for his Gervase Fen novels but here he spins a delightfully black tale of a struggling writer whose hospitality is impinged upon by a pair of runaways, both seeking a new life away from their spouses. Crispin intersperses the narrative with vivid accounts of a writer desperately searching for the words which will bring his latest novel to life. Sadly for the would-be lovers, their fate is to be organic fertiliser for Mr Bradley’s vegetable plot.

Crispin, aka Robert Bruce Montgomery, is best known for his Gervase Fen novels but here he spins a delightfully black tale of a struggling writer whose hospitality is impinged upon by a pair of runaways, both seeking a new life away from their spouses. Crispin intersperses the narrative with vivid accounts of a writer desperately searching for the words which will bring his latest novel to life. Sadly for the would-be lovers, their fate is to be organic fertiliser for Mr Bradley’s vegetable plot. Davidson’s internationally themed thrillers were his bread and butter, but we must not forget that he was a writer of immense sensitivity with a wide range of influences. His own upbringing as a child of a hard-scrabble Polish-Jewish family might have made it unlikely that he would compose a chilling tale of murder on the banks of s Scottish river frequented only by rich Englishmen with the money to buy the rights to snare incoming salmon. A man whose sexual abilities have been devastated by a potentially fatal illness plans revenge on a friend whose libido remains undiminished. The denouement takes place on the banks of Scotland’s sacred salmon river – the Spey.

Davidson’s internationally themed thrillers were his bread and butter, but we must not forget that he was a writer of immense sensitivity with a wide range of influences. His own upbringing as a child of a hard-scrabble Polish-Jewish family might have made it unlikely that he would compose a chilling tale of murder on the banks of s Scottish river frequented only by rich Englishmen with the money to buy the rights to snare incoming salmon. A man whose sexual abilities have been devastated by a potentially fatal illness plans revenge on a friend whose libido remains undiminished. The denouement takes place on the banks of Scotland’s sacred salmon river – the Spey. Colin Dexter? Cue Oxford, an irascible senior policeman, pints of English beer and crossword puzzles? Think on. When this story was published, Dexter was already four books into his Inspector Morse series, but the TV adaptations were still six years away. In this tale, Dexter takes us to, of all places, rural America, where a coach load of middle-aged and elderly tourists take a rest stop at the eponymous wayside hotel. The action is centred around a game of vingt-et-un, designed to empty the wallets of the gullible travellers. Dexter describes a scam-within-a -scam -but saves until the last few paragraphs a chilling finale in which the scammer becomes the scammed.

Colin Dexter? Cue Oxford, an irascible senior policeman, pints of English beer and crossword puzzles? Think on. When this story was published, Dexter was already four books into his Inspector Morse series, but the TV adaptations were still six years away. In this tale, Dexter takes us to, of all places, rural America, where a coach load of middle-aged and elderly tourists take a rest stop at the eponymous wayside hotel. The action is centred around a game of vingt-et-un, designed to empty the wallets of the gullible travellers. Dexter describes a scam-within-a -scam -but saves until the last few paragraphs a chilling finale in which the scammer becomes the scammed. People might forget that Antonia Fraser, as well as being the daughter of Lord Longford the widow of Harold Pinter and a superb historical biographer, is no slouch when it comes to crime fiction. Here, she taps into that strange love affair that English people have with their dogs. Richard Gavin is a successful barrister (is there ever another sort?) who has kept his upper lip stiff and tremble-free during the death of his first wife, and remarried. The new lady of the Gavin household is Paulina – young. bright and adorable. Her judgment, however is brought into question, when her decision to put an aged, smelly and incontinent spaniel out of its misery coincides with Richard opening an ominous letter from his London doctor.

People might forget that Antonia Fraser, as well as being the daughter of Lord Longford the widow of Harold Pinter and a superb historical biographer, is no slouch when it comes to crime fiction. Here, she taps into that strange love affair that English people have with their dogs. Richard Gavin is a successful barrister (is there ever another sort?) who has kept his upper lip stiff and tremble-free during the death of his first wife, and remarried. The new lady of the Gavin household is Paulina – young. bright and adorable. Her judgment, however is brought into question, when her decision to put an aged, smelly and incontinent spaniel out of its misery coincides with Richard opening an ominous letter from his London doctor. This is the most shocking and slap-in-the-face story in the collection. I would go as far as to suggest that it would not have been written – let alone published – today, with our heightened awareness of child abuse and domestic violence. As an account of casual violence, domestic cruelty, alcohol abuse – and the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic church – it makes for uncomfortable reading. Highsmith’s misanthropy can never have been more glaringly or honestly displayed. her publisher wrote:

This is the most shocking and slap-in-the-face story in the collection. I would go as far as to suggest that it would not have been written – let alone published – today, with our heightened awareness of child abuse and domestic violence. As an account of casual violence, domestic cruelty, alcohol abuse – and the pervasive power of the Roman Catholic church – it makes for uncomfortable reading. Highsmith’s misanthropy can never have been more glaringly or honestly displayed. her publisher wrote: Like Hubbard’s longer works, which are examined in this feature, a dream-like quality pervades this story, but the dreams are not necessarily pleasant ones. The first words are:

Like Hubbard’s longer works, which are examined in this feature, a dream-like quality pervades this story, but the dreams are not necessarily pleasant ones. The first words are: This exquisite masterpiece tells of a nameless girl, an orphan, who is brought up in a loveless terraced house in east London, the home of her Uncle Victor and Aunt Gladys. Her only joy is the adjacent cemetery which becomes a place of mystical and endless attraction:

This exquisite masterpiece tells of a nameless girl, an orphan, who is brought up in a loveless terraced house in east London, the home of her Uncle Victor and Aunt Gladys. Her only joy is the adjacent cemetery which becomes a place of mystical and endless attraction:

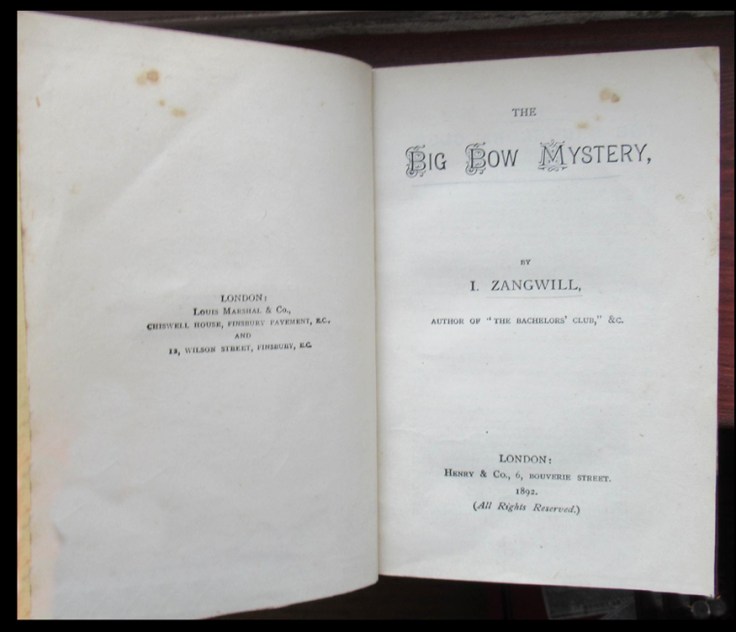

The ‘Bow’ in the title is not some fabric adornment, but the working class district in East London. If you were born within earshot of its church bells, then you were said to be a true Cockney. It’s December, and the nineteenth century is on its last legs. A dense morning fog, aided and abetted by the smoke of a million coal fires, swirls around the mean streets.

The ‘Bow’ in the title is not some fabric adornment, but the working class district in East London. If you were born within earshot of its church bells, then you were said to be a true Cockney. It’s December, and the nineteenth century is on its last legs. A dense morning fog, aided and abetted by the smoke of a million coal fires, swirls around the mean streets. The formidable lady has overslept, but after lighting the downstairs fire, she remembers to wake one of the lodgers. Arthur Constant is an idealist, and a campaigner for workers’ rights. She bangs on his bedroom door, then makes the day’s first pot of tea. Taking a tray upstairs, she calls again. Still no response. She peeps through the keyhole, but the key is firmly in place. As she pounds on the door once again, she has a premonition that something is very, very wrong. So she summons her neighbour, the redoubtable retired detective Mr George Grodman. He batters down the door, which was locked and bolted from the inside, and is forced to cover Mrs Drabdump’s eyes from the horrors within…

The formidable lady has overslept, but after lighting the downstairs fire, she remembers to wake one of the lodgers. Arthur Constant is an idealist, and a campaigner for workers’ rights. She bangs on his bedroom door, then makes the day’s first pot of tea. Taking a tray upstairs, she calls again. Still no response. She peeps through the keyhole, but the key is firmly in place. As she pounds on the door once again, she has a premonition that something is very, very wrong. So she summons her neighbour, the redoubtable retired detective Mr George Grodman. He batters down the door, which was locked and bolted from the inside, and is forced to cover Mrs Drabdump’s eyes from the horrors within… Some contemporary critics were puzzled and irritated by Zangwill’s satirical style. They felt that there was no place for comedy in the tale of a young man, dead in his bed, his throat cut from ear to ear. The exchanges in the court scenes between pompous officials and outspoken ‘low life’ types on the jury are delightfully reminiscent of similar encounters between Mr Pooter and disrespectful tradesmen in that classic of English humour, The Diary of A Nobody.

Some contemporary critics were puzzled and irritated by Zangwill’s satirical style. They felt that there was no place for comedy in the tale of a young man, dead in his bed, his throat cut from ear to ear. The exchanges in the court scenes between pompous officials and outspoken ‘low life’ types on the jury are delightfully reminiscent of similar encounters between Mr Pooter and disrespectful tradesmen in that classic of English humour, The Diary of A Nobody.