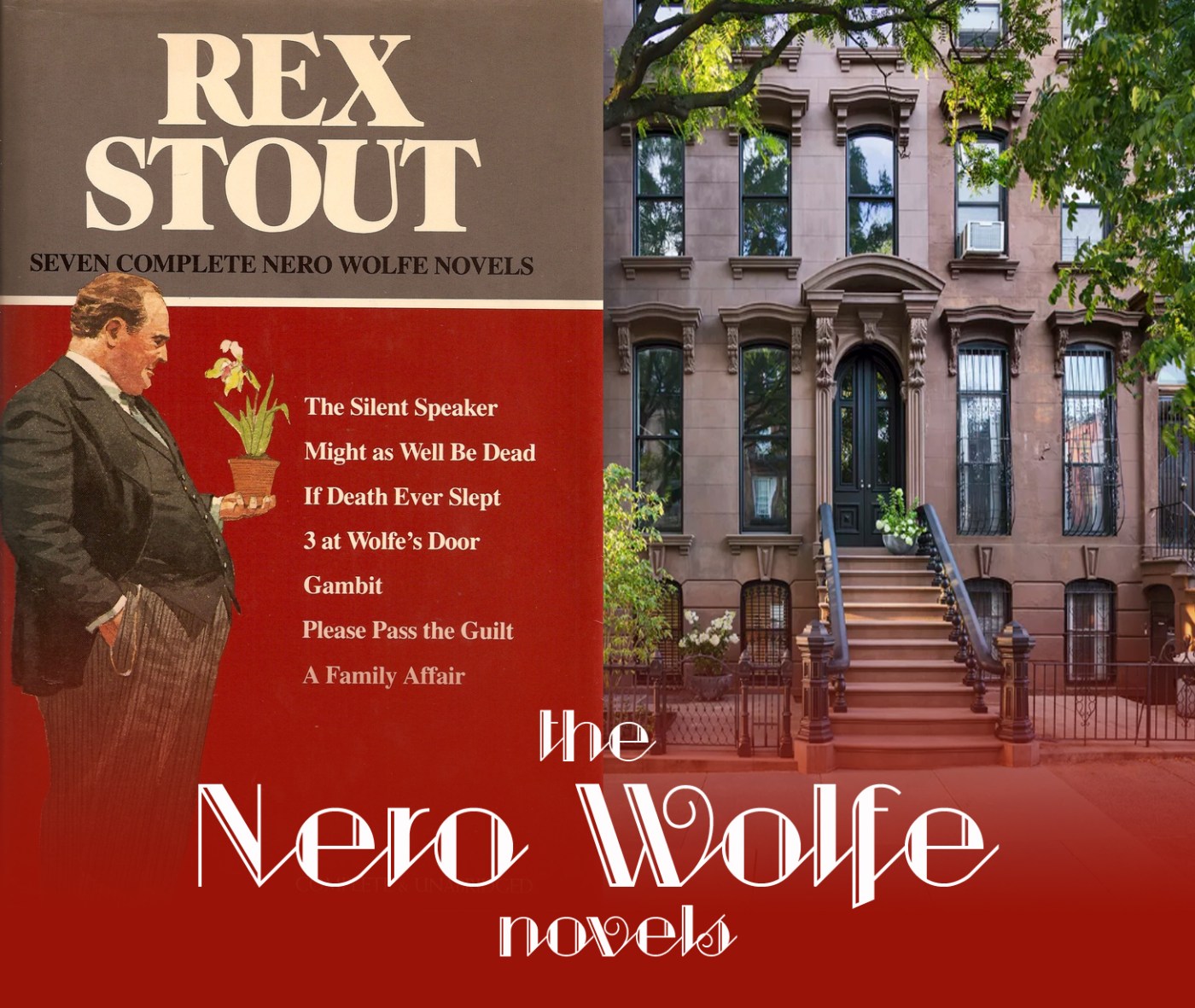

Fer-de-Lance was published in 1934 by Farrar & Rinehart, Inc. I doubt there will be any readers living for whom this novel was their introduction to the series. Most, like me, will have read one of the other 45 first. I mention this because it is astonishing how Stout brings the curtain up on the whole Wolfe household so that we feel we have known them for ever. Not for him the clumsy explanations or contrived insertion of the back-story. “Here they are”, he seems to say, “.. let’s get on with the story.”

And what a story it is. A wealthy and highly regarded academic, Peter Oliver Barstow dies from an apparent heart attack while he is engaged in a foursome on a golf course. Meanwhile, an Italian metalworker, Carlo Maffei, has disappeared, but then turns up – as a corpse – murdered, if the knife embedded in his chest is anything to go by. As Wolfe uses his phenomenal intellect to link these cases, we learn that he is partial to a glass (or six) of beer. Bear in mind that Prohibition in America had only ended in 1933. Wolfe, perhaps disheartened by the lack of a decent drink, decides to cut down on his intake:

And what a story it is. A wealthy and highly regarded academic, Peter Oliver Barstow dies from an apparent heart attack while he is engaged in a foursome on a golf course. Meanwhile, an Italian metalworker, Carlo Maffei, has disappeared, but then turns up – as a corpse – murdered, if the knife embedded in his chest is anything to go by. As Wolfe uses his phenomenal intellect to link these cases, we learn that he is partial to a glass (or six) of beer. Bear in mind that Prohibition in America had only ended in 1933. Wolfe, perhaps disheartened by the lack of a decent drink, decides to cut down on his intake:

“I’m going to cut down to three quarts a day. Twelve bottles. A bottle doesn’t hold a pint. I am now going to bed.”

Archie is sent (because Wolfe rarely if ever leaves the house) to interrogate the residents of the house where Maffei lived. Archie Goodwin, remember, is the sole narrator of these stories. He sums up Anna Fiore:

“I went over and shook hands with her. She was a homely kid about twenty with skin like stale dough, and she looked like she’d been scared in the cradle and never got over it.”

It turns out that Barstow was killed by a poison dart which was loaded into the specially prepared shaft of a golf club. The club’s shaft was adapted by the late Carlo Maffei to release its deadly projectile when the face of the club head made contact with the ball. Wolfe directs operations from the brownstone house, where he sits like a fat spider at the centre of a deadly web. When it emerges that Barstow was not the intended victim, and that the truth behind the killing implicates so many people, Wolfe pronounces:

“It is an admirable dilemma; I have rarely seen one with so many horns and all of them so sharp.”

Eventually, of course, after encounters with a deadly snake and a a scheming attorney, the mystery is solved, but not before Wolfe demonstrates that he is prepared to dispense his own rather harsh brand of justice. We are also treated to his own lordly – and almost Dickensian – use of language:

“I have just being explaining to Mr Anderson that the ingenious theory of the Barstow case which he is trying to embrace is an offence to truth and an outrage to justice, and since I cherish the one and am on speaking terms with the other, it is my duty to demonstrate its inadequacy.”

The relationship between Archie Goodwin and Nero Wolfe lies at the heart of these novels. There is a sense of servant and master, and Goodwin clearly worships the ground that Wolfe walks on, despite his frequent frustrations and occasional attempts to ruffle Wolfe’s imperious demeanour. In his own magisterial way, Wolfe treats Goodwin like a much-loved but slightly wayward son. This affection occasionally gives way to acerbic put-downs:

“Some day, Archie, when I decide you are no longer worth tolerating, you will have to marry a woman of very modest mental capacity to get an appropriate audience for your wretched sarcasms.”

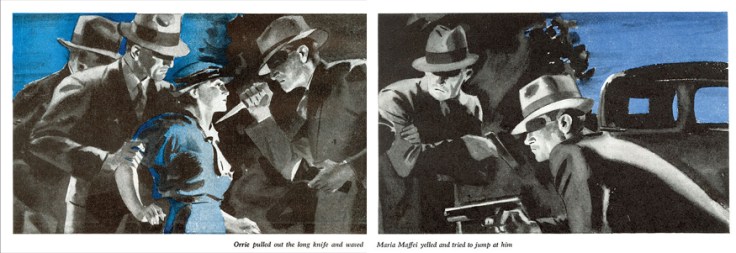

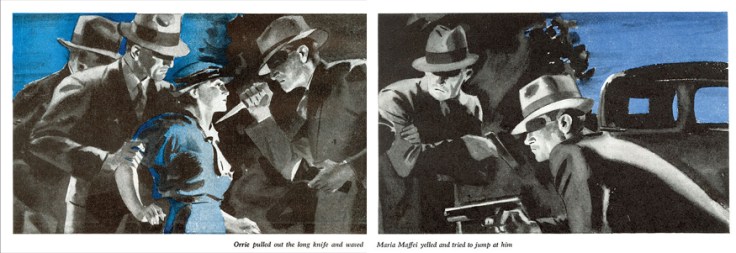

Stout always had a weather eye open for commercial opportunities, and he was able to arrange for an abbreviated version of this story to be re-hashed as a pulp short story re-named Point of Death – complete with illustrations.

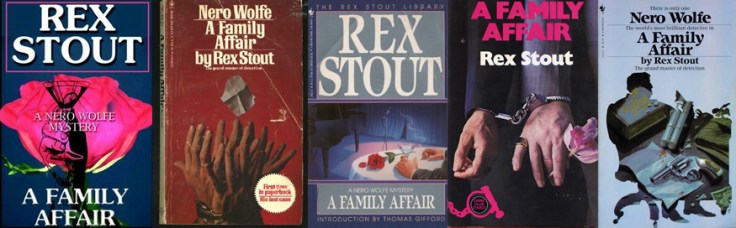

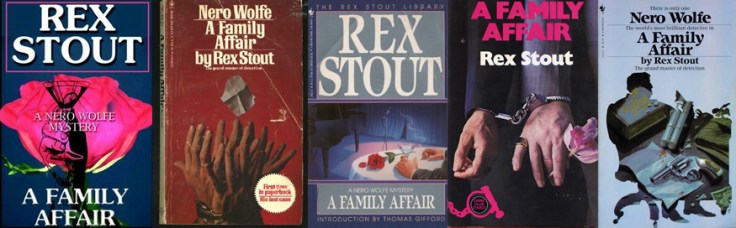

Almost the first thing which strikes you as you settle in to read A Family Affair (1975) is the sheer breadth of real life events straddled by the Nero Wolfe novels. When Fer de Lance was published America was in the dying throes of Prohibition, John Dillinger, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow had only recently been shot dead, but Pretty Boy Floyd was still at large. By the time Stout’s final novel was published, America was still reeling from the Watergate scandal, Nixon had resigned, The Rocky Horror Show had opened on Broadway, and a man called Bill Gates was playing around with words which could describe his new micro software.

Almost the first thing which strikes you as you settle in to read A Family Affair (1975) is the sheer breadth of real life events straddled by the Nero Wolfe novels. When Fer de Lance was published America was in the dying throes of Prohibition, John Dillinger, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow had only recently been shot dead, but Pretty Boy Floyd was still at large. By the time Stout’s final novel was published, America was still reeling from the Watergate scandal, Nixon had resigned, The Rocky Horror Show had opened on Broadway, and a man called Bill Gates was playing around with words which could describe his new micro software.

If you want a literally explosive opening to a novel, look no further. Late at night, Paul Ducos, a waiter from Wolfe’s favourite New York restaurant, rings the bell on the front door of the old brownstone, and beseeches Archie to let him speak to Wolfe. He says his life is in imminent danger. Fearful of waking his boss at such an inhospitable hour, Archie compromises, and allows the fearful Frenchman to stay the night in a spare room, with the promise of an audience with Wolfe in the morning.

As Archie prepares for bed, the house shakes and there is a terrible noise. The spare bedroom being bolted from the inside, he clambers in through the shattered window via the fire escape, and sees Ducos lying on the floor:

“He had no face left. I had never seen anything like it. It was about what you would get if you pressed a thick slab of pie dough on a man’s face and then squirted blood on the lower half.”

We learn fairly quickly that Ducos has been killed by a bomb he was inadvertently carrying. A doctored aluminium cigar tube had been planted in his jacket. He discovered it and, fatally, unscrewed the cap. Wolfe reacts to the death with barely suppressed fury. Ducos is dead, yes, but the real assault is on his sanctuary, his own home, the place he values so much that he rarely leaves it.

Archie – assisted by the usual supernumaries Saul Panzer, Fred Durkin and Ollie Cather – is turned loose to find out who killed Paul Ducos. One of the leads takes Archie to the dead man’s home which he shares with his father and daughter. The old man is wheelchair bound, and speaks no English, and the young woman is unwilling – or unable to help. Archie is unimpressed by the contents of her bookshelves and has something to say about Lucile Ducos’s espousal of the feminist agenda:

“All right, she’s a phony. A woman who has those books with her name in them wants men to stop making women sex symbols, and if she really wants them to stop she wouldn’t keep her skin like that, and her hair, and blow her hard-earned pay on a dress that sets her off. Of course she can’t help her legs. She’s a phony.”

It becomes clear that Paul Ducos was a bit-player in a wide screen drama involving senior industrialists and lawyers, one of whom died the week before the waiter was killed. When Lucile Ducos is also killed, Archie and Wolfe find themselves not working alongside the local cops, but prime suspects, and they spend several uncomfortable hours under lock and key. When they are released, and despite the demands of the case, Wolfe does not lose his appetite, neither does master chef Fritz Brenner succumb to the pressure:

“He tasted his lunch, alright. First marrow dumplings, and then sweetbreads poached in white wine, dipped in crumbs and eggs, sautéed and then doused with almonds in brown butter.”

This is one of the more serious and deadly episodes in the career of New York’s most celebrated private investigator, but there is still time for humour. Wolfe’s magisterial demeanour and studied delivery does not go un-noticed or unchecked by his right-hand man:

“’Whom did you hear say what?’

I have tried to talk him out of “whom”. Only grandstanders and schoolteachers say “whom”, and he knows it. It’s the mule in him.”

The Goodwin-Wolfe partnership has never come under such strain, and the servant comes within a couple of breaths of finally severing ties with his master but, thanks to a social link with Archie’s long-time lady friend. Lily Rowan, it dawns on all concerned that the villain of the piece is not one of the highly placed lawyers or politicians, but someone much closer to home. By the by, Archie’s admiration for Lily Rowan is unashamed, but he cannot resist a seasoning of irony:

“I’d buy a pedestal and put her on it if I thought she’d stay. She would either fall off or climb down. I don’t know which.”

Eventually, in a chilling and brutal conclusion, justice of a kind is served. Wolfe and Archie escape the clutches of the District Attorney and his officers, but there is a final knock on the door from an angry policeman. Fully aware of his machinations but frustrated by Wolfe’s ability to enforce his own law while remaining invulnerable to the laws of the city of New York, Inspector Cramer lashes out, bitterly, but his barb simply bounces off and rolls harmlessly into a dark corner of the office:

Eventually, in a chilling and brutal conclusion, justice of a kind is served. Wolfe and Archie escape the clutches of the District Attorney and his officers, but there is a final knock on the door from an angry policeman. Fully aware of his machinations but frustrated by Wolfe’s ability to enforce his own law while remaining invulnerable to the laws of the city of New York, Inspector Cramer lashes out, bitterly, but his barb simply bounces off and rolls harmlessly into a dark corner of the office:

“He went and got his coat and put it on and came back, to the corner of Wolfe’s desk, and said, ‘I’m going home and try to get some sleep. You probably have never had to try to get some sleep. You probably never will.’”

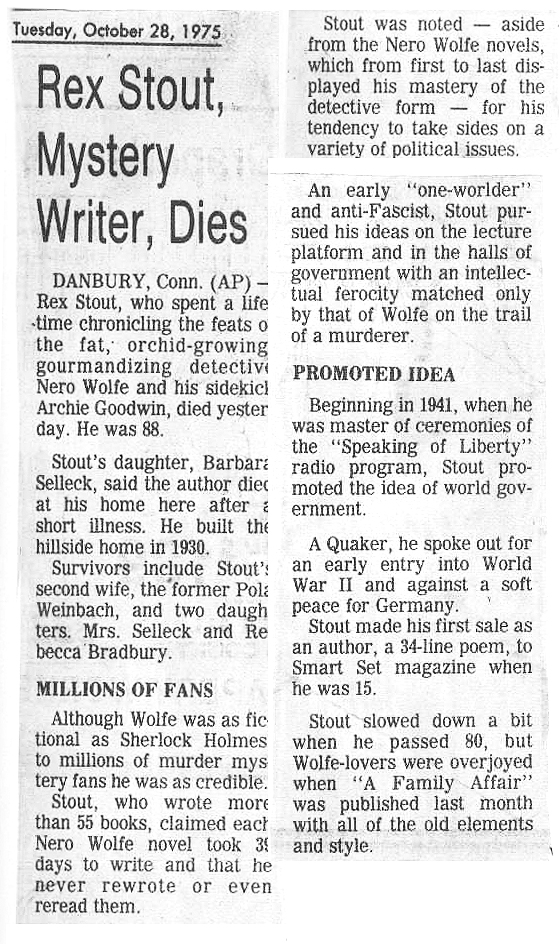

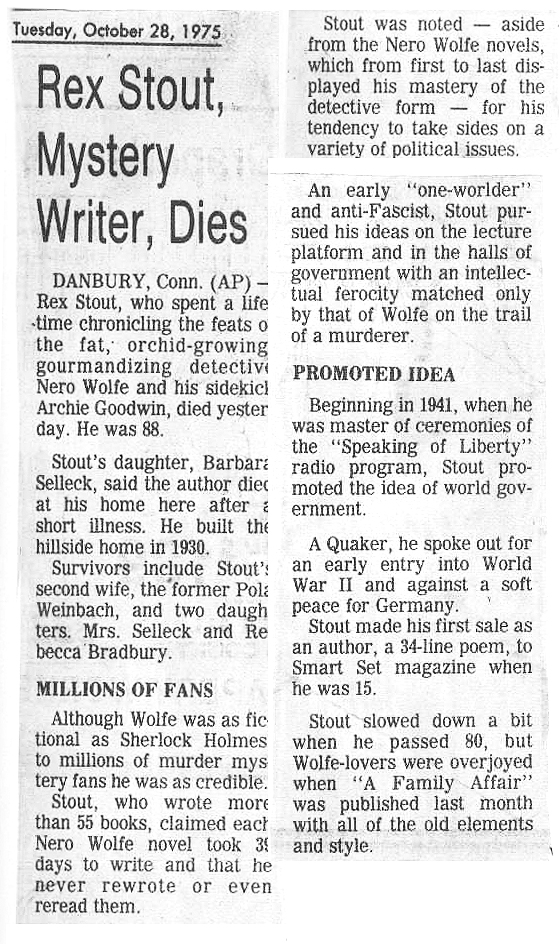

This is the last episode in the long and illustrious career of the gargantuan, pompous – but eerily perceptive consulting detective. Of his origins we learn little, except that he is, by origin, a Montenegran, and that he has an aged mother living in Budapest to whom he sends money. It is tempting to ascribe elegiac qualities to Wolfe’s last bow. Rex Stout was to die in the same year as the novel was published. Wolfe had survived the greatest challenge – a challenge made from within his trusted family, and a challenge aimed at the high altar of his own church – the brownstone on West 35thStreet. That altar has been desecrated but, in the end, Wolfe clings to his certainties.

“When the sound came of the front door closing, Wolfe said,

‘Will you bring brandy, Archie?’”

The last word should go to Thomas Gifford (1937 – 2000) who was no slouch at crime writing himself.

“Through Wolfe and Archie, Stout shows you how people are supposed to behave. How grownups act when the pressure is on. So in the very best and wisest sense, and quite painlessly too, Stout shares his code with you, and you are improved a bit.. You would be hard pressed to find another popular writer of his era who more subtly and ably defined what it was to be civilised, to have standards.”

PART ONE of our celebration of the Nero Wolfe novels is HERE

And what a story it is. A wealthy and highly regarded academic, Peter Oliver Barstow dies from an apparent heart attack while he is engaged in a foursome on a golf course. Meanwhile, an Italian metalworker, Carlo Maffei, has disappeared, but then turns up – as a corpse – murdered, if the knife embedded in his chest is anything to go by. As Wolfe uses his phenomenal intellect to link these cases, we learn that he is partial to a glass (or six) of beer. Bear in mind that Prohibition in America had only ended in 1933. Wolfe, perhaps disheartened by the lack of a decent drink, decides to cut down on his intake:

And what a story it is. A wealthy and highly regarded academic, Peter Oliver Barstow dies from an apparent heart attack while he is engaged in a foursome on a golf course. Meanwhile, an Italian metalworker, Carlo Maffei, has disappeared, but then turns up – as a corpse – murdered, if the knife embedded in his chest is anything to go by. As Wolfe uses his phenomenal intellect to link these cases, we learn that he is partial to a glass (or six) of beer. Bear in mind that Prohibition in America had only ended in 1933. Wolfe, perhaps disheartened by the lack of a decent drink, decides to cut down on his intake:

Almost the first thing which strikes you as you settle in to read A Family Affair (1975) is the sheer breadth of real life events straddled by the Nero Wolfe novels. When Fer de Lance was published America was in the dying throes of Prohibition, John Dillinger, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow had only recently been shot dead, but Pretty Boy Floyd was still at large. By the time Stout’s final novel was published, America was still reeling from the Watergate scandal, Nixon had resigned, The Rocky Horror Show had opened on Broadway, and a man called Bill Gates was playing around with words which could describe his new micro software.

Almost the first thing which strikes you as you settle in to read A Family Affair (1975) is the sheer breadth of real life events straddled by the Nero Wolfe novels. When Fer de Lance was published America was in the dying throes of Prohibition, John Dillinger, Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow had only recently been shot dead, but Pretty Boy Floyd was still at large. By the time Stout’s final novel was published, America was still reeling from the Watergate scandal, Nixon had resigned, The Rocky Horror Show had opened on Broadway, and a man called Bill Gates was playing around with words which could describe his new micro software.

Eventually, in a chilling and brutal conclusion, justice of a kind is served. Wolfe and Archie escape the clutches of the District Attorney and his officers, but there is a final knock on the door from an angry policeman. Fully aware of his machinations but frustrated by Wolfe’s ability to enforce his own law while remaining invulnerable to the laws of the city of New York, Inspector Cramer lashes out, bitterly, but his barb simply bounces off and rolls harmlessly into a dark corner of the office:

Eventually, in a chilling and brutal conclusion, justice of a kind is served. Wolfe and Archie escape the clutches of the District Attorney and his officers, but there is a final knock on the door from an angry policeman. Fully aware of his machinations but frustrated by Wolfe’s ability to enforce his own law while remaining invulnerable to the laws of the city of New York, Inspector Cramer lashes out, bitterly, but his barb simply bounces off and rolls harmlessly into a dark corner of the office:

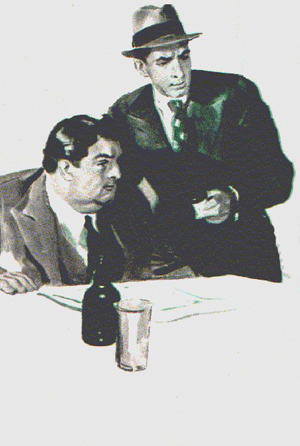

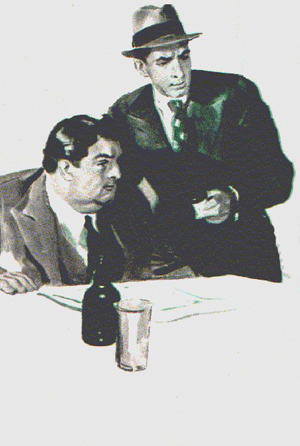

For all that Stout was an intellectual and a vigorous campaigner for what he believed in, his legacy remains the creation of Nero Wolfe. Wolfe is an obese, physically lazy but improbably intelligent detective who loves his food and alcohol, cultivates orchids, but never leaves his brownstone house on New York’s West 35th Street. Much of Wolfe’s crime solving is done from the comfort of his armchair, or while consuming fine food and drink. His mind can only achieve so much, however, and he needs access to the streets. This comes in the form of Archie Goodwin (pictured left in a period illustration). Archie would, in truth, have made a perfectly good PI on his own. He is physically fit, handsome, as sharp as a tack, and can handle himself when it comes to physical violence. He lives on another floor of Wolfe’s house, and according to a memo written from Rex Stout to a friend, Archie is:

For all that Stout was an intellectual and a vigorous campaigner for what he believed in, his legacy remains the creation of Nero Wolfe. Wolfe is an obese, physically lazy but improbably intelligent detective who loves his food and alcohol, cultivates orchids, but never leaves his brownstone house on New York’s West 35th Street. Much of Wolfe’s crime solving is done from the comfort of his armchair, or while consuming fine food and drink. His mind can only achieve so much, however, and he needs access to the streets. This comes in the form of Archie Goodwin (pictured left in a period illustration). Archie would, in truth, have made a perfectly good PI on his own. He is physically fit, handsome, as sharp as a tack, and can handle himself when it comes to physical violence. He lives on another floor of Wolfe’s house, and according to a memo written from Rex Stout to a friend, Archie is:

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

The Dancing Man was published in 1971, and is set in Welsh hill country. An engineer, Mark Hawkins travels to a remote house to collect his late brother’s belongings. Dick Hawkins was an archaeologist by profession and mountaineering was his drug of choice. He set off one day for the nearby mountains, and never returned.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure.

With A Thirsty Evil (1974) Hubbard once again mines Shakespeare for his title, in this case, Measure For Measure. The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

The story moves swiftly on. Hubbard’s novels are, anyway, relatively short but his narrative drive never lets us rest. Beth’s carnality and opportunism get the better of Mackellar in a brief but shocking encounter, but this is only a staging post on the path to a violent and tragic conclusion to the novel. Mackellar survives, but he writes his own epitaph in the very first chapter.

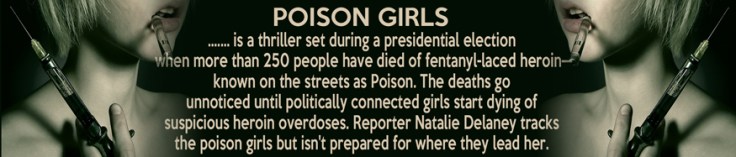

Cheryl Reed

Cheryl Reed

I didn’t have to meet Theodore. But I would argue that my new debut novel, Poison Girls, is much richer for my having done so. Theodore was just one of many real characters I met as I explored the underbelly of the heroin drug culture, researching the real story of fentanyl-laced heroin in Chicago that killed more than 250 people in a few months. One thing I learned working for more than two decades as a journalist—many of those as a crime reporter—is that real people are far more complex and interesting than solely relying on my imagination. I’ve read a lot of books and watched a lot of movies that feature drug dealers and drug fixers, but I’ve never read one named Theodore who wore a candy necklace that he chewed on with a single fang. Shit like that, you just can’t make up.

I didn’t have to meet Theodore. But I would argue that my new debut novel, Poison Girls, is much richer for my having done so. Theodore was just one of many real characters I met as I explored the underbelly of the heroin drug culture, researching the real story of fentanyl-laced heroin in Chicago that killed more than 250 people in a few months. One thing I learned working for more than two decades as a journalist—many of those as a crime reporter—is that real people are far more complex and interesting than solely relying on my imagination. I’ve read a lot of books and watched a lot of movies that feature drug dealers and drug fixers, but I’ve never read one named Theodore who wore a candy necklace that he chewed on with a single fang. Shit like that, you just can’t make up.

Flush As May (1963) takes its title from a soliloquy by Hamlet, and Hubbard sets the piece in an ostensibly idyllic rural England, contemporary with the time of the novel’s publication. Margaret Canting is an Oxford undergraduate staying in the nearby village of Lodstone She takes it upon herself to see in May Morning, not by carolling from the top of a church tower, but with a dawn stroll. Her idyll is interrupted when she finds the corpse of a man, sleeping his final sleep against the grassy bank at the edge of a field.

Flush As May (1963) takes its title from a soliloquy by Hamlet, and Hubbard sets the piece in an ostensibly idyllic rural England, contemporary with the time of the novel’s publication. Margaret Canting is an Oxford undergraduate staying in the nearby village of Lodstone She takes it upon herself to see in May Morning, not by carolling from the top of a church tower, but with a dawn stroll. Her idyll is interrupted when she finds the corpse of a man, sleeping his final sleep against the grassy bank at the edge of a field.

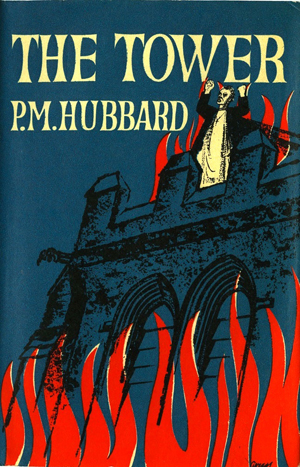

The Tower (1968) begins with Hubbard tipping his hat in a gentlemanly fashion in the direction of a lady. The lady is none other than Dorothy L Sayers. Her masterpiece (other opinions are available), The Nine Tailors, begins with Bunter and Lord Peter abandoning their car in a snowy ditch outside a remote Fenland village. So it is that John Smith, the central character in The Tower, finds his car refusing to travel an inch further on an inky black night, a mile or so outside the village of Coyle. That, however is pretty much where the homage ends. Coyle is a far more sinister place that Fenchurch St Peter, and its vicar, Father Freeman, is infinitely less benevolent than dear old Reverend Venables.

The Tower (1968) begins with Hubbard tipping his hat in a gentlemanly fashion in the direction of a lady. The lady is none other than Dorothy L Sayers. Her masterpiece (other opinions are available), The Nine Tailors, begins with Bunter and Lord Peter abandoning their car in a snowy ditch outside a remote Fenland village. So it is that John Smith, the central character in The Tower, finds his car refusing to travel an inch further on an inky black night, a mile or so outside the village of Coyle. That, however is pretty much where the homage ends. Coyle is a far more sinister place that Fenchurch St Peter, and its vicar, Father Freeman, is infinitely less benevolent than dear old Reverend Venables.

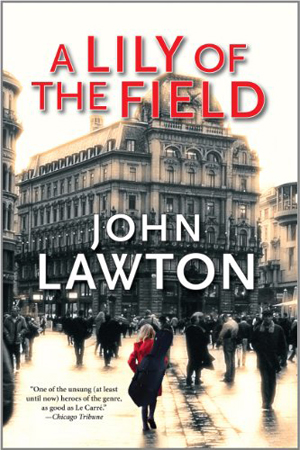

John Lawton is a master of historical fiction set in and around World War II. His central character is Fred Troy, a policeman of Russian descent. His emigré father is what used to be called a ‘Press Baron’. Fred’s brother Rod will go on to become a Labour Party MP in the 1960s, but is interned during the war. His sisters are bit players, but memorable for their sexual voracity. Neither man nor woman is safe from their advances.

John Lawton is a master of historical fiction set in and around World War II. His central character is Fred Troy, a policeman of Russian descent. His emigré father is what used to be called a ‘Press Baron’. Fred’s brother Rod will go on to become a Labour Party MP in the 1960s, but is interned during the war. His sisters are bit players, but memorable for their sexual voracity. Neither man nor woman is safe from their advances.

I do love Operas, though – at least those written up to the death of Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini (who would be just as wonderful even if he didn’t have six christian names.) I would add the personal caveat that for me it is sometimes better heard than seen, as stage productions can sometimes demand too much suspension of disbelief. Our chosen book, then, is Spur Of The Moment by David Linzee, and it is set around the St Louis Opera company as they prepare a performance of Bizet’s wonderful, preposterous, exhilarating four-act classic, Carmen.

I do love Operas, though – at least those written up to the death of Giacomo Antonio Domenico Michele Secondo Maria Puccini (who would be just as wonderful even if he didn’t have six christian names.) I would add the personal caveat that for me it is sometimes better heard than seen, as stage productions can sometimes demand too much suspension of disbelief. Our chosen book, then, is Spur Of The Moment by David Linzee, and it is set around the St Louis Opera company as they prepare a performance of Bizet’s wonderful, preposterous, exhilarating four-act classic, Carmen. David Linzee has himself been a ‘supernumary’ – basically the opera equivalent of a spear carrier – and he enjoys several digs at the way an opera company in a mid-sized city is run. I particularly enjoyed his jibes at the ubiquitous need for sponsorship. Linzee (right) explains that the SLO has to make sure that literally every brick in the building has corporate support. Thus we have the Peter J Calvocoressi Administration Building, the Charles Macnamara III Auditorium and – best of all – the Endeavour Rent-a-Car Endowed Artist. In this case it’s Amy Song, the woman playing Carmen.

David Linzee has himself been a ‘supernumary’ – basically the opera equivalent of a spear carrier – and he enjoys several digs at the way an opera company in a mid-sized city is run. I particularly enjoyed his jibes at the ubiquitous need for sponsorship. Linzee (right) explains that the SLO has to make sure that literally every brick in the building has corporate support. Thus we have the Peter J Calvocoressi Administration Building, the Charles Macnamara III Auditorium and – best of all – the Endeavour Rent-a-Car Endowed Artist. In this case it’s Amy Song, the woman playing Carmen.

Before he had the brainwave which gave us Merrily Watkins in The Wine of Angels (1998), Rickman wrote several standalone novels. The most music-centred one was December (1994). It begins on the evening of Monday 8th December, 1980. For most people of a certain age, that date will be an instant trigger, but Rickman (right) sets us down in a ruined abbey in the remote Welsh hamlet of Ystrad Ddu, which sits at the foot of one of The Black Mountains, Ysgyryd Fawr – more commonly known by its anglicised form The Skirrid. Part of the medieval abbey has been fitted out as a recording studio and, in a cynical act of niche marketing, a record impresario has contracted a folk rock band, The Philosopher’s Stone, to record an album of mystical songs in the haunted building, and he has stipulated that the tracks must be laid down between midnight and dawn.

Before he had the brainwave which gave us Merrily Watkins in The Wine of Angels (1998), Rickman wrote several standalone novels. The most music-centred one was December (1994). It begins on the evening of Monday 8th December, 1980. For most people of a certain age, that date will be an instant trigger, but Rickman (right) sets us down in a ruined abbey in the remote Welsh hamlet of Ystrad Ddu, which sits at the foot of one of The Black Mountains, Ysgyryd Fawr – more commonly known by its anglicised form The Skirrid. Part of the medieval abbey has been fitted out as a recording studio and, in a cynical act of niche marketing, a record impresario has contracted a folk rock band, The Philosopher’s Stone, to record an album of mystical songs in the haunted building, and he has stipulated that the tracks must be laid down between midnight and dawn.