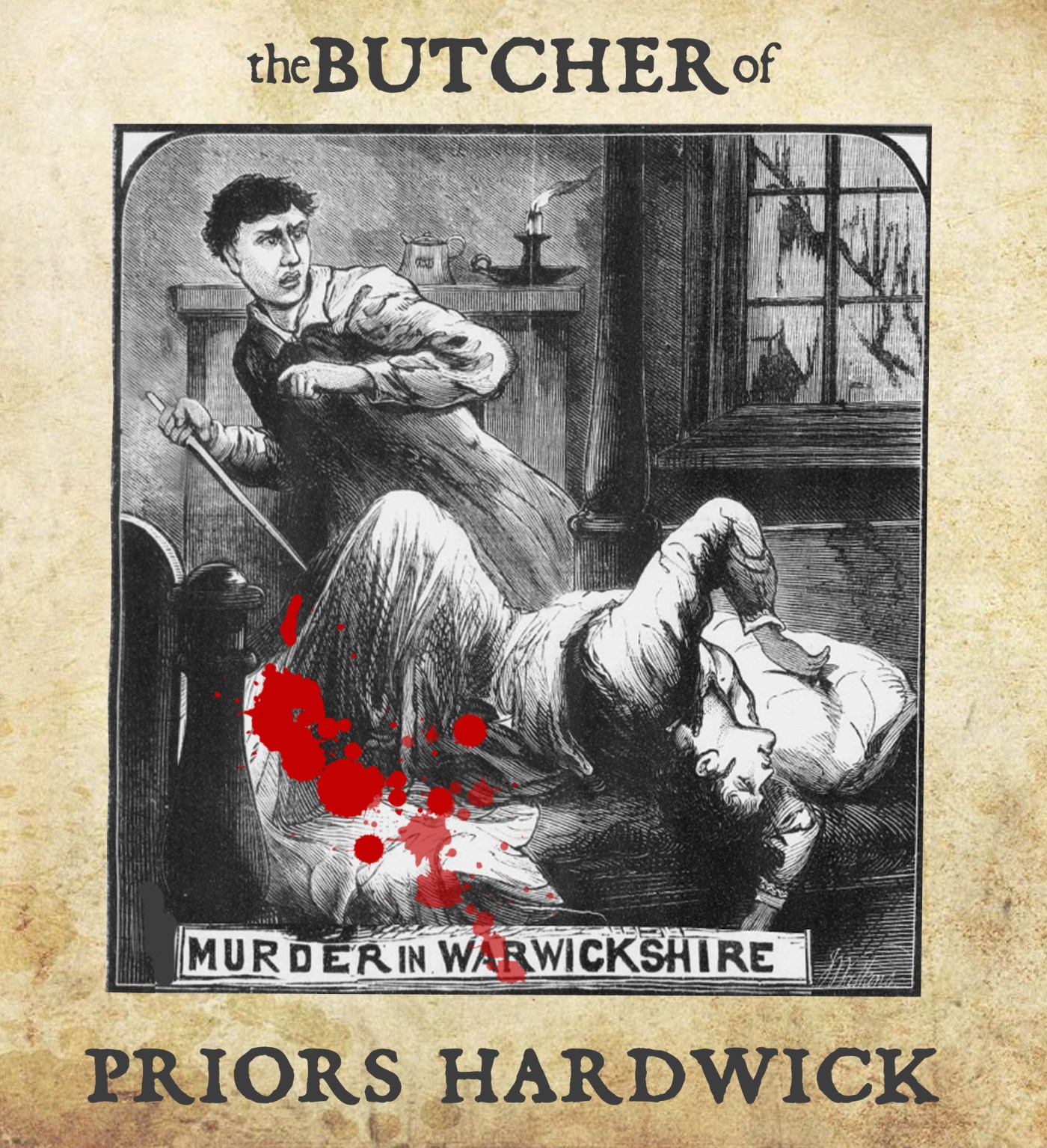

SO FAR: November 1872. Edward Handcock, 58, a jobbing slaughterman and butcher, lives with his third wife, Betsy, and their children, in a tiny cottage on London End, Priors Hardwick. He is prone to bouts of drunkenness, and is a profoundly jealous man. He is convinced that Betsy, ten years his junior is, to use his own words, “whoring”. On the evening of 13th November, things come to a head. A subsequent newspaper report tells the grim tale.

Edward Handcock was immediately arrested. Betsy Handcock was buried a few days later in the village churchyard.

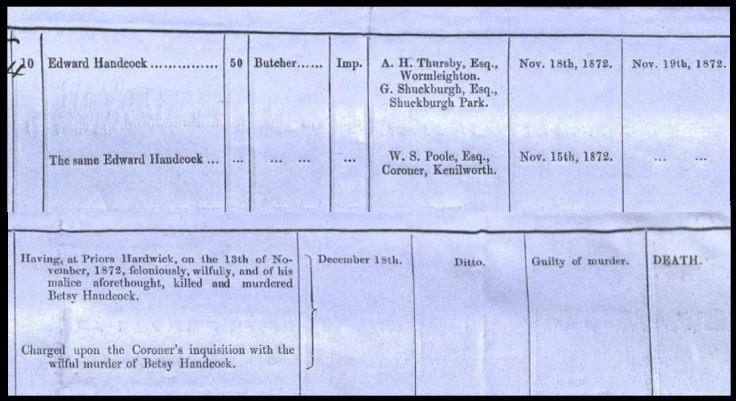

The procedure with suspected murder cases was relatively straightforward in concept, but could be lengthy. First came the coroner’s inquest, before a jury, to establish cause of death and a recommendation for the next stage which, if a suspect was believed guilty, was the local magistrate court. Finally, the suspect would be sent for trial at the county assize court, before a senior judge. The inquest on Betsy Handcock was held on 15th November at the village pub, The Butchers Arms – an appropriate venue in a macabre way. The medical evidence makes for grim reading:

Mr. Bragge, surgeon, of Priors Marston, said he saw the deceased woman just before eight o’clock, and found her in a comatose condition, but still partly sensible. He asked her what was the matter, and she pointed to her thigh. Examining the wound he found there was bleeding, and at once ordered her into a warm bed, and administered stimulants. She died in a few minutes after she was placed in the bed. He had made a post-mortem examination, and found the femoral artery in the left thigh bad been severed by a clean-cut wound. The wound was deep, and such as might have been caused by the knife produced. There was also a small punctured wound under the left armpit, and two small cuts on the left arm. The wounds could not have been inflicted by the deceased. Mr. Rice, surgeon, of Southam, gave corroborative evidence. He said the cut the in thigh severed the femoral artery and the vessels.

The worst part of these various hearings was that the two principal witnesses to the murder were the children, Walter and Eliza. It was necessary for them to relive the ordeal three times over; first at the inquest, then in front of the Southam magistrates on 18th November, and then a third and final time in the much more intimidating surroundings of Warwick Assizes. The magistrates court was presided over by Major George Shuckburgh (left). Walter testified:

“My father’s name is Edward Handcock. I returned home from my work at Mr. Mumford’s (Prior’s Marston) Wednesday last about half-past five in the evening. I had my tea by myself as soon I got home. Before I began my tea mother said she would go and fetch a policeman, and she left the house. I did not hear what passed between my father and mother before she went out. My father remained in the house after mother went away, and was in an adjoining room from where I was. After my mother left the house I heard my father sharpen his knife. I did not see him. but l am quite sure did so. My mother was gone about five-and-twenty minutes. She did not bring a policeman with her. I had finished my tea when she came back. Before my mother came back, my father went upstairs. I did not observe him take anything with him. I remained downstairs. When my mother came back, my father threw the casement of the window down into the court. I did not see him do it, but I heard the wood fall. My mother undressed the children when she came home. The children’s names are Eliza, Peter, and Minnie. After they were undressed, she took them upstairs, and said she expected there would be a “pillilu” when she took them up. I heard my mother say “Walter, Walter, he’s cutting me.” and I ran out of the house to tell the next door neighbour, Edward Prestidge.”

Edward Handcock was duly sent for trial at the December Assizes, in front of Sir George Bramwell Knight, and he was found guilty and sentenced to death on 18th December. What kind of Christmas he had doesn’t bear thinking about, but on Tuesday 7th January 1873, he was led to the scaffold inside Warwick Gaol. The executioner was George Smith, known as “Throttler Smith”. What was known as ‘the long drop’, where the condemned person died almost instantaneously, was some way off, and Handcock’s death was certainly not swift.

FOR MORE HISTORIC WARWICKSHIRE CRIMES

CLICK THE IMAGE BELOW

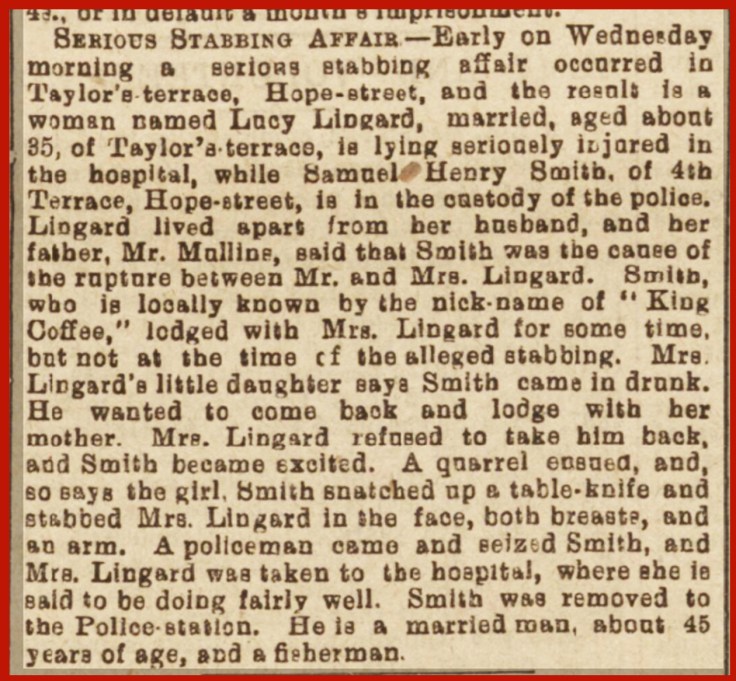

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

The report was overly optimistic. Lucy Lingard hovered between life and death for a while, but on the Sunday, four days after the attack, she died of her injuries, described below at the subsequent inquest.

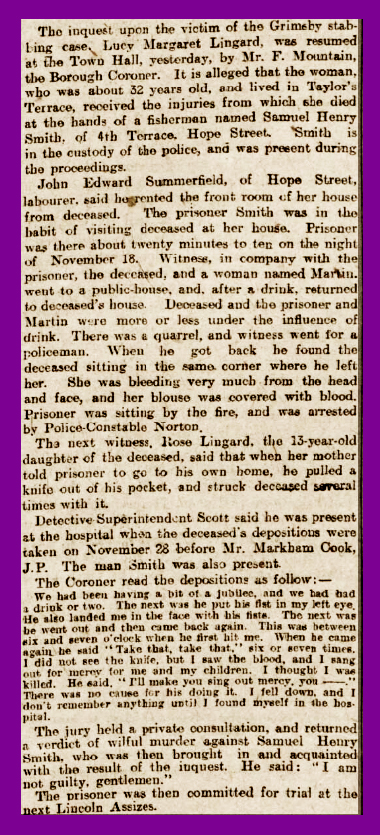

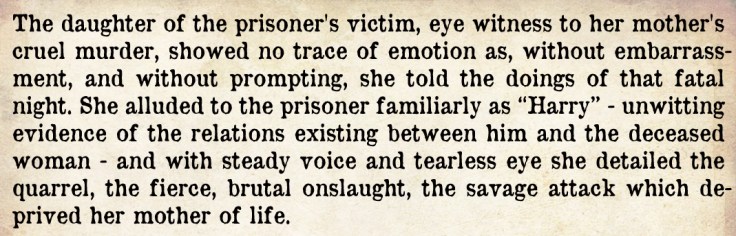

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Inevitably, the Coroner’s court, convened at the beginning of December, declared Smith to be guilty of murder, and now it would be up to the Lincoln Assizes court, Judge and Jury, to determine his fate. Smith spent the rest of December – including Christmas – and the greater part of February in Lincoln gaol. On Wednesday 25th February 1903, before Mr Justice Kennedy (right), Samuel Henry Smith ‘had his hour in court’. Despite the suggestion to the jury that the charge should be reduced to one of manslaughter, it all went badly for Smith.

Hope Street in Grimsby was cleared of its terraces in the late 1960s (pictured above, thanks to Hope Street History), but a late 19th century map shows back-to-back houses opening directly onto the street, and every so often there would courtyards, each open area being surrounded on three sides by further dwellings. For those interested in the history of Hope Street, there is a Facebook page that gives access to an excellent pdf document describing the history of the street. That link is

Hope Street in Grimsby was cleared of its terraces in the late 1960s (pictured above, thanks to Hope Street History), but a late 19th century map shows back-to-back houses opening directly onto the street, and every so often there would courtyards, each open area being surrounded on three sides by further dwellings. For those interested in the history of Hope Street, there is a Facebook page that gives access to an excellent pdf document describing the history of the street. That link is

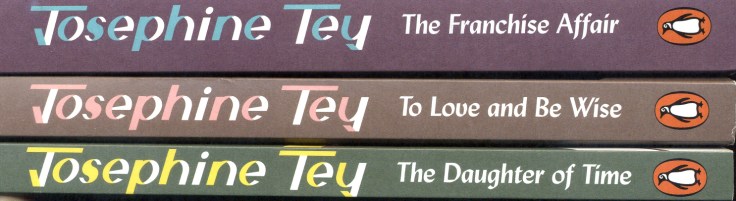

Penguin have a treat in store for fans of British ‘Golden Age’ crime novels. On 22nd September they are publishing new editions of three novels by a woman who many people feel deserves to be up there with Allingham, Christie, Marsh and Sayers in the Pantheon of female crime fiction giants.

Penguin have a treat in store for fans of British ‘Golden Age’ crime novels. On 22nd September they are publishing new editions of three novels by a woman who many people feel deserves to be up there with Allingham, Christie, Marsh and Sayers in the Pantheon of female crime fiction giants.