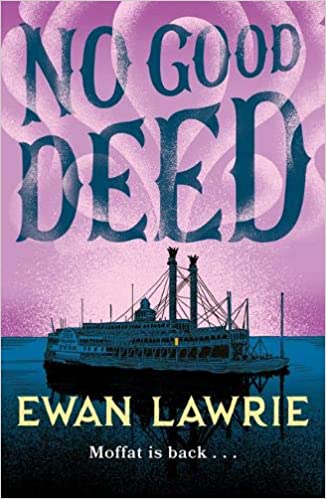

First, a word about the author, Ewan Lawrie (left). He comes to the book world by a rather different route than many of his fellow writers. There cannot be many authors who served for nigh on a quarter of a century in the armed forces – in this case, the RAF – and then turned to writing. His first novel, Gibbous House, (2017) introduced us to a gentleman called Alasdair Moffat, who rejoices in the appellation Moffat the Magniloquent. In that novel he was a prosperous and successful criminal in Victorian London, but now, a decade later, he – having fallen on hard times – has relocated to America, along with countless other folk of the “huddled masses”, the “wretched refuse” and the “tempest-tossed”. Unlike them, however, he is not seeking the “lamp beside the golden door”, but a rather better place in which to exercise his criminal talents.

First, a word about the author, Ewan Lawrie (left). He comes to the book world by a rather different route than many of his fellow writers. There cannot be many authors who served for nigh on a quarter of a century in the armed forces – in this case, the RAF – and then turned to writing. His first novel, Gibbous House, (2017) introduced us to a gentleman called Alasdair Moffat, who rejoices in the appellation Moffat the Magniloquent. In that novel he was a prosperous and successful criminal in Victorian London, but now, a decade later, he – having fallen on hard times – has relocated to America, along with countless other folk of the “huddled masses”, the “wretched refuse” and the “tempest-tossed”. Unlike them, however, he is not seeking the “lamp beside the golden door”, but a rather better place in which to exercise his criminal talents.

It is 1861, and America is on the verge of the disastrous conflict which will shape the nation’s future for decades to come. Moffat has fetched up in St Louis, pretty much stony broke. With an unerring talent for sniffing out trouble, he murders a man named Anson Northrup, assumes his identity and, in order to pay off a brothel bill he cannot afford, accepts the task of delivering a mysterious package further down the Mississippi River. He boards the steam-driven riverboat The Grand Turk. The package he is carrying contains operational details of what was known as The Underground Railroad – a network of secret routes and safe houses established in America used by slaves to escape into freedom. Moffat, of course, being British, takes the metaphor literally, and it is some time before he realises that he is not carrying a conventional railway timetable, and that the late Anson Northrup is a key figure in a plot to steal silver bullion from the Mint in New Orleans – the major city in the state of Louisiana, which had just seceded from the United States.

In his guise as Northrup (although not everyone is fooled) Moffat meets several larger-than-life and almost grotesque fictional characters, and lurches from one crisis to the next, but one of the most spectacular parts of the novel is when he meets Marie Laveau, a real life New Orleans character renowned for her mystical qualities, as well as her expertise in the black arts of voodoo.

In his guise as Northrup (although not everyone is fooled) Moffat meets several larger-than-life and almost grotesque fictional characters, and lurches from one crisis to the next, but one of the most spectacular parts of the novel is when he meets Marie Laveau, a real life New Orleans character renowned for her mystical qualities, as well as her expertise in the black arts of voodoo.

Lawrie is an entertaining writer who has clearly done his historical homework, but also adds a heady combination of whimsy, smart jokes and improbable situations to make for an entertaining read. The rather old fashioned literary term picaresque came into my mind as I was reading this, but I needed to check what it meant. The ever-present Google says that it is:

“relating to an episodic style of fiction dealing with the adventures of a rough and dishonest but appealing hero.”

I think that pretty much sums up No Good Deed. The novel succeeds not through the particular integrity of the plot, but more through the relentlessly entertaining episodes, and the grim allure of Moffat himself. There is more than a touch of George MacDonald Fraser and his likeable coward Harry Flashman about this book, and I can thoroughly recommend it to anyone who enjoyed that series of novels. No Good Deed is published by Unbound Digital, and is out now.

This has the most seriously sinister beginning of any crime novel I have read in years. DI Henry Hobbes (of whom more presently) is summoned by his Sergeant to Bridlemere, a rambling Edwardian house in suburban London, where an elderly man has apparently committed suicide. Corpse – tick. Nearly empty bottle of vodka – tick. Sleeping pills on the nearby table – tick. Hobbes is not best pleased at his time being wasted, but the observant Meg Latimer has a couple of rabbits in her hat. One rabbit rolls up the dead man’s shirt to reveal some rather nasty knife cuts, and the other leads Hobbes on a tour round the house, where he discovers identical sets of women’s clothing, all laid out formally, and each with gashes in the midriff area, stained red. Sometimes the stains are actual blood, but others are as banal as paint and tomato sauce.

This has the most seriously sinister beginning of any crime novel I have read in years. DI Henry Hobbes (of whom more presently) is summoned by his Sergeant to Bridlemere, a rambling Edwardian house in suburban London, where an elderly man has apparently committed suicide. Corpse – tick. Nearly empty bottle of vodka – tick. Sleeping pills on the nearby table – tick. Hobbes is not best pleased at his time being wasted, but the observant Meg Latimer has a couple of rabbits in her hat. One rabbit rolls up the dead man’s shirt to reveal some rather nasty knife cuts, and the other leads Hobbes on a tour round the house, where he discovers identical sets of women’s clothing, all laid out formally, and each with gashes in the midriff area, stained red. Sometimes the stains are actual blood, but others are as banal as paint and tomato sauce.

My verdict on House With No Doors? In a nutshell, brilliant – a tour de force. Jeff Noon (right) has taken the humble police procedural, blended in a genuinely frightening psychological element, added a layer of human corruption and, finally, seasoned the dish with a piquant dash of insanity. On a purely narrative level, he also includes one of the most daring and astonishing final plot twists I have read in many a long year.

My verdict on House With No Doors? In a nutshell, brilliant – a tour de force. Jeff Noon (right) has taken the humble police procedural, blended in a genuinely frightening psychological element, added a layer of human corruption and, finally, seasoned the dish with a piquant dash of insanity. On a purely narrative level, he also includes one of the most daring and astonishing final plot twists I have read in many a long year.