Deborah Masson’s police procedural Hold Your Tongue is as gritty as the granite in the Aberdeen where it is set. Fictional Detective Inspectors tend to be brilliant, yet with fatal flaws; perceptive, but incapable of managing calm personal lives; honest and principled, but concealing their own dark secrets. Masson’s Eve Hunter ticks all the boxes, and adds a few of her own. She is returning to work after a catastrophic encounter with a notorious criminal family. After the son of the crime gang’s Capo sustains life changing injuries in a car chase, Johnny MacNeill has exacted brutal revenge resulting in Hunter’s partner DS Nicola Sanders being paralysed from the neck down, while Hunter herself has a permanently damaged leg and intense psychological scarring.

Deborah Masson’s police procedural Hold Your Tongue is as gritty as the granite in the Aberdeen where it is set. Fictional Detective Inspectors tend to be brilliant, yet with fatal flaws; perceptive, but incapable of managing calm personal lives; honest and principled, but concealing their own dark secrets. Masson’s Eve Hunter ticks all the boxes, and adds a few of her own. She is returning to work after a catastrophic encounter with a notorious criminal family. After the son of the crime gang’s Capo sustains life changing injuries in a car chase, Johnny MacNeill has exacted brutal revenge resulting in Hunter’s partner DS Nicola Sanders being paralysed from the neck down, while Hunter herself has a permanently damaged leg and intense psychological scarring.

There is no ‘Welcome Back’ party for Hunter. There are former colleagues who blame her impulsive and driven approach to police work for what happened to Nicola Sanders. Her boss doubts she is ready for a return, particularly as her first case will be to solve the savage murder of an aspiring model, found dead in a hotel room, surrounded by an elaborate and deliberate staging of fashion magazines, make-up and mirrors. Melanie Ross’s tongue has been cut out, and taken away by her killer.

Masson makes telling use of Aberdeen itself as a baleful presence looming behind the misdeeds of its citizens. Despite the grim grandeur of its municipal buildings, the passing of the North Sea oil bonanza has left a legacy of closed shops and tatty, uncared-for neighbourhoods. A prostitute called Rosie, who is involved with one of the suspects, provides a chilling metaphor for the city:

“Rosie pulled together the edges of the flimsy unbuttoned black raincoat that she wore; it barely concealed the bony chest in a low-cut top and laddered fishnets below a skirt that could pass as easily for a belt.”

The pre-Christmas weather is vile and utterly inhospitable. The sleety rain slants down, the wind blows in squalls from the North Sea, and the grey light of dawn reveals city streets slick, wet and icy, decorated only with discarded takeaway meals, the odd abandoned high-heeled shoe, and a general air of attempts at gaiety which ended in failure.

More murders follow, and they are clearly the work of the same person. Eventually Hunter realises what the elaborate posing of the victims signifies. The killer has somehow become obsessed with the old nursery fable:

Monday’s child is fair of face

Tuesday’s child is full of grace,

Wednesday’s child is full of woe,

Thursday’s child has far to go,

Friday’s child is loving and giving,

Saturday’s child works hard for a living,

But the child who is born on the Sabbath Day

Is bonny and blithe and good and gay.

As the killer works towards the Sabbath Day child, Hunter and her colleagues dash this way and that, always vital hours behind the murderer. Masson (right) contributes to the mayhem with some elegantly clever misdirection. Early in the piece she teases us with the suggestion that the series of murders has something to do with brothers and sisters, but even when we – and Eve Hunter – think we are close to the truth, there is one big surprise left. Hold Your Tongue is an assured and convincing debut, and I hope there will be more cases to come for Eve Hunter. The book is out now, and published by Corgi/Penguin.

As the killer works towards the Sabbath Day child, Hunter and her colleagues dash this way and that, always vital hours behind the murderer. Masson (right) contributes to the mayhem with some elegantly clever misdirection. Early in the piece she teases us with the suggestion that the series of murders has something to do with brothers and sisters, but even when we – and Eve Hunter – think we are close to the truth, there is one big surprise left. Hold Your Tongue is an assured and convincing debut, and I hope there will be more cases to come for Eve Hunter. The book is out now, and published by Corgi/Penguin.

Val McDermid’s wonderful odd couple Tony Hill and Carol Jordan don’t have it in them, for a variety of complex reasons, to love each other in any conventional sense, and

Val McDermid’s wonderful odd couple Tony Hill and Carol Jordan don’t have it in them, for a variety of complex reasons, to love each other in any conventional sense, and  James Lee Burke celebrated his eighty third birthday earlier this month and, thankfully, shows no sign that his powers have deserted him. His brooding and haunted Louisiana lawman Dave Robicheux returned in

James Lee Burke celebrated his eighty third birthday earlier this month and, thankfully, shows no sign that his powers have deserted him. His brooding and haunted Louisiana lawman Dave Robicheux returned in  There is an understandable temptation to lionise a book, irrespective of its merit, when it is published posthumously, the last work of a fine writer who died far too soon.

There is an understandable temptation to lionise a book, irrespective of its merit, when it is published posthumously, the last work of a fine writer who died far too soon.  Sometimes, the sheer bravura, joy and energy of a writer’s work makes us happily turn a blind eye to improbabilities. Let’s face it, Christopher Fowler’s Arthur Bryant and John May have been solving crimes since the Luftwaffe was raining bombs down on London and, by rights, they should be, like Betjeman’s Murray Posh and Lupin Pooters “Long in Kelsal Green and Highgate silent under soot and stone.” But they live on, and long may they defy Father Time. In

Sometimes, the sheer bravura, joy and energy of a writer’s work makes us happily turn a blind eye to improbabilities. Let’s face it, Christopher Fowler’s Arthur Bryant and John May have been solving crimes since the Luftwaffe was raining bombs down on London and, by rights, they should be, like Betjeman’s Murray Posh and Lupin Pooters “Long in Kelsal Green and Highgate silent under soot and stone.” But they live on, and long may they defy Father Time. In

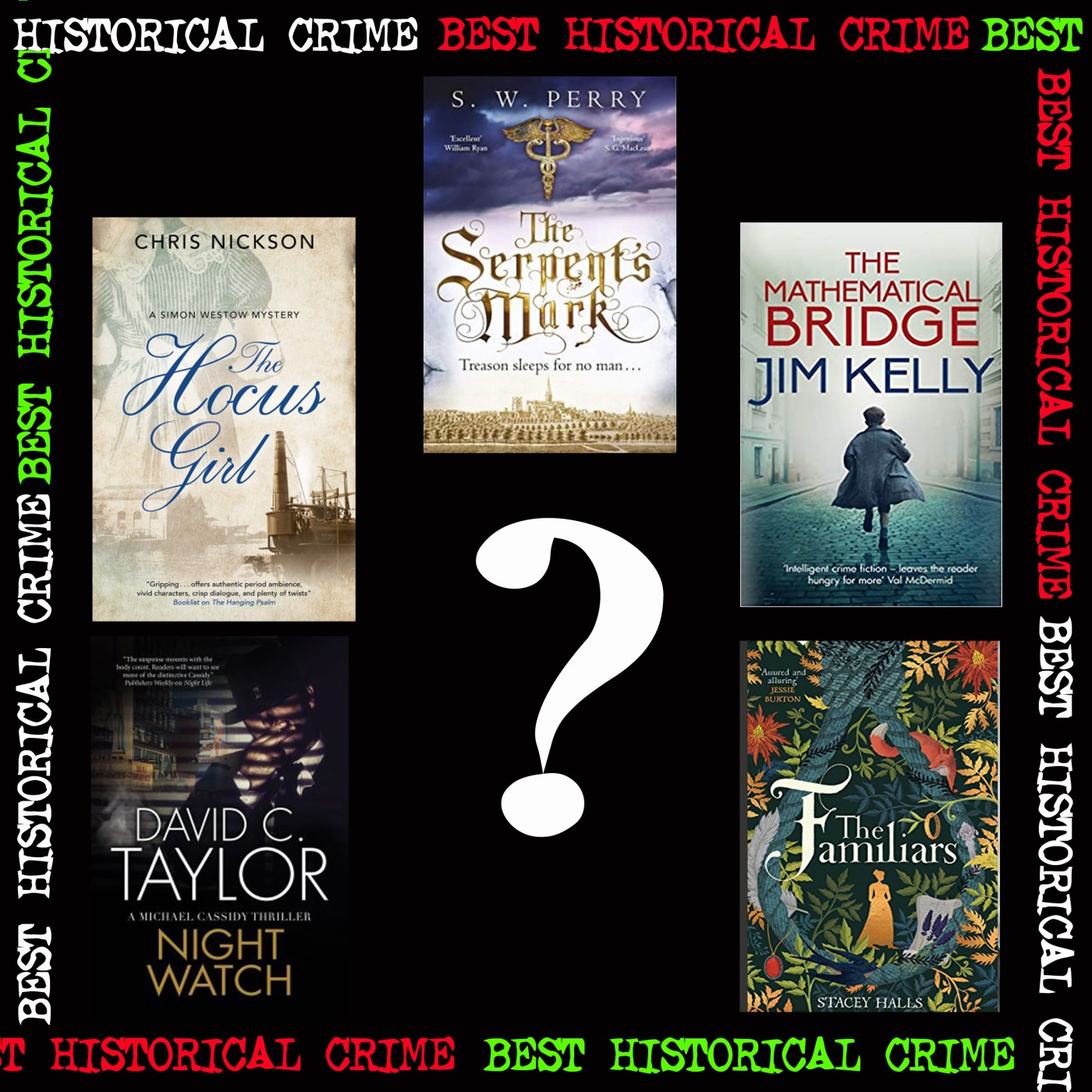

The Familiars

The Familiars Chris Nickson’s historical novels may be narrow in geographical scope – they are mostly set in Leeds across the centuries – but they are magnificent in their emotional, political and social breadth. In

Chris Nickson’s historical novels may be narrow in geographical scope – they are mostly set in Leeds across the centuries – but they are magnificent in their emotional, political and social breadth. In  SW Perry has written an excellent thriller about religious extremism, media manipulation and political treachery. The fact that

SW Perry has written an excellent thriller about religious extremism, media manipulation and political treachery. The fact that  For all that the era was in my lifetime, the 1950s may just as well be the 1650s given the gulf between then and the modern world. In

For all that the era was in my lifetime, the 1950s may just as well be the 1650s given the gulf between then and the modern world. In

There are some very special Irish crime writers these days. Some mine the uniquely bitter and bleak seam of Belfast, with its raw and recent memories, while further south the city of Dublin, where “the girls are so pretty”, has its fair share of malcontents and evil doers. Olivia Kiernan and her Chief Superintendent Frankie Sheehan were new to me, but

There are some very special Irish crime writers these days. Some mine the uniquely bitter and bleak seam of Belfast, with its raw and recent memories, while further south the city of Dublin, where “the girls are so pretty”, has its fair share of malcontents and evil doers. Olivia Kiernan and her Chief Superintendent Frankie Sheehan were new to me, but  Staying in Ireland, it has to be said that Jo Spain is ridiculously talented. She has created a bankable stock character in the affable Dublin copper Tom Reynolds, but this has not stopped her from writing such brilliant stand-alones as

Staying in Ireland, it has to be said that Jo Spain is ridiculously talented. She has created a bankable stock character in the affable Dublin copper Tom Reynolds, but this has not stopped her from writing such brilliant stand-alones as  Vulnerability as a character trait is perhaps more common in British fictional coppers that their American counterparts, and few fit that bill quite like James Oswald’s Edinburgh detective Tony McLean.

Vulnerability as a character trait is perhaps more common in British fictional coppers that their American counterparts, and few fit that bill quite like James Oswald’s Edinburgh detective Tony McLean.  In

In

Tim Weaver’s intrepid searcher for the physically lost, David Raker, faced his hardest challenge yet in

Tim Weaver’s intrepid searcher for the physically lost, David Raker, faced his hardest challenge yet in  Clergymen writing crime novels? That can only mean cosy village mysteries centred around tweedy villages and eccentric old ladies, surely? Not if Peter Laws has his way. He is a minister in the Baptist Church in Bedforshire, but his Matthew Hunter novels are dark, scary and blood-spattered. In

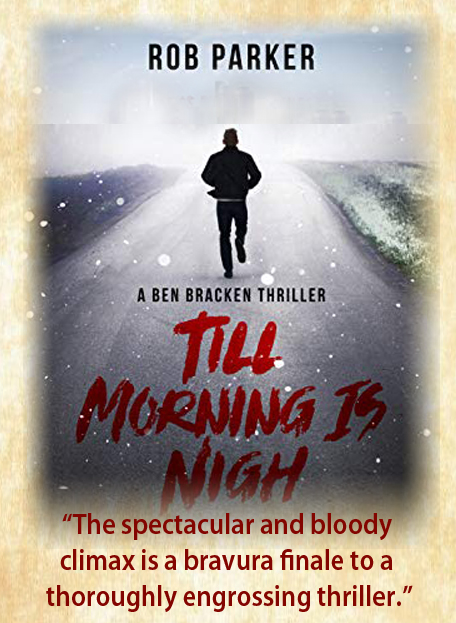

Clergymen writing crime novels? That can only mean cosy village mysteries centred around tweedy villages and eccentric old ladies, surely? Not if Peter Laws has his way. He is a minister in the Baptist Church in Bedforshire, but his Matthew Hunter novels are dark, scary and blood-spattered. In  Ben Bracken is a Jack Reacher do-alike transported to contemporary England. Much as I have enjoyed the invincible Reacher over the years, Rob Parker has created a more thoughtful and vulnerable – at least psychologically – version in Ben Bracken, a former soldier who exists in the shady hinterland which lies between law enforcement, special services and officially-sanctioned skullduggery.

Ben Bracken is a Jack Reacher do-alike transported to contemporary England. Much as I have enjoyed the invincible Reacher over the years, Rob Parker has created a more thoughtful and vulnerable – at least psychologically – version in Ben Bracken, a former soldier who exists in the shady hinterland which lies between law enforcement, special services and officially-sanctioned skullduggery.  Sad to say, there is no-one more vulnerable in modern society – at least in novels – than a single mother trying to bring up her child. In

Sad to say, there is no-one more vulnerable in modern society – at least in novels – than a single mother trying to bring up her child. In

here is an debate in the Twittersphere at this time of year about whether Die Hard is, or isn’t a Christmas movie. Maybe there is also a discussion to be had as to whether this latest adventure for Rob Parker’s invincible iron man, Ben Bracken, is a Christmas thriller. Those with young children, or fond memories of their own childhood, will surely recognise the source of the book’s title. Preface it with the words “And stay by my cradle ..” and you should have the answer.

here is an debate in the Twittersphere at this time of year about whether Die Hard is, or isn’t a Christmas movie. Maybe there is also a discussion to be had as to whether this latest adventure for Rob Parker’s invincible iron man, Ben Bracken, is a Christmas thriller. Those with young children, or fond memories of their own childhood, will surely recognise the source of the book’s title. Preface it with the words “And stay by my cradle ..” and you should have the answer. We are in a wintry Manchester. The time is the present. As usual, the giant plastic Santa is hoist by his breeches on the Victorian gothic façade of the town hall, dispensing silent jollity to the shoppers and merry-makers scurrying beneath his furry boots. In Albert Square, homeless men try to find solace in their threadbare coats, wondering where the next coffee, the next Greggs pasty – or the next fix of chemical oblivion – is going to come from.

We are in a wintry Manchester. The time is the present. As usual, the giant plastic Santa is hoist by his breeches on the Victorian gothic façade of the town hall, dispensing silent jollity to the shoppers and merry-makers scurrying beneath his furry boots. In Albert Square, homeless men try to find solace in their threadbare coats, wondering where the next coffee, the next Greggs pasty – or the next fix of chemical oblivion – is going to come from. mong these sad footnotes to the tidings of comfort and joy, Ben Bracken moves, asking questions. The former soldier, imprisoned in nearby Strangeways for something he didn’t do, has escaped and now leads a perilous existence employed by a shadowy government agency who have uses for his particular skillset, which involves an immense capacity for violence and superb fieldcraft honed both in the killing fields of Afghanistan and the mean streets of Britain’s cities.

mong these sad footnotes to the tidings of comfort and joy, Ben Bracken moves, asking questions. The former soldier, imprisoned in nearby Strangeways for something he didn’t do, has escaped and now leads a perilous existence employed by a shadowy government agency who have uses for his particular skillset, which involves an immense capacity for violence and superb fieldcraft honed both in the killing fields of Afghanistan and the mean streets of Britain’s cities. ack in the real world for a moment, we are told by experts that the biggest terrorist threat to our society in Britain comes from right wing extremist organisations. Only a few days ago a number of men – all fans of Hitler, Breivik and other assorted homicidal lunatics – were convicted of planning terrorism via social media. The fictional group which Ben Bracken infiltrates are, however, not pimply twenty-somethings operating out of a bedroom in their mum’s house, but serious players, ex-military and financing their ambitions via the trade in hard drugs. They are well trained, armed with more than just a Facebook account, and they mean business.

ack in the real world for a moment, we are told by experts that the biggest terrorist threat to our society in Britain comes from right wing extremist organisations. Only a few days ago a number of men – all fans of Hitler, Breivik and other assorted homicidal lunatics – were convicted of planning terrorism via social media. The fictional group which Ben Bracken infiltrates are, however, not pimply twenty-somethings operating out of a bedroom in their mum’s house, but serious players, ex-military and financing their ambitions via the trade in hard drugs. They are well trained, armed with more than just a Facebook account, and they mean business. Parker is a fine young writer. He can muse ruefully on the inadequate protection the human body has against steel wielded with extreme malice:

Parker is a fine young writer. He can muse ruefully on the inadequate protection the human body has against steel wielded with extreme malice:

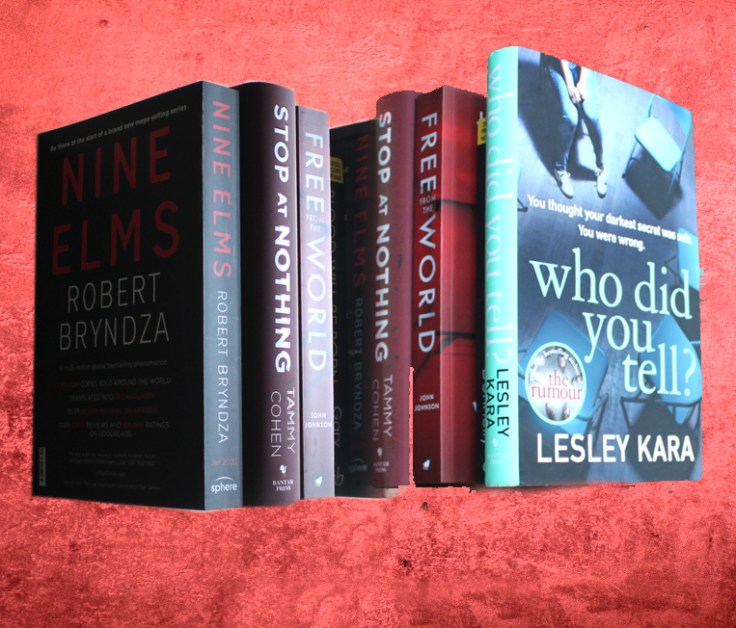

Bryndza already has an established audience for his Detective Erika Foster series, and he now introduces another female copper to the crime scene. Fifteen years earlier, Kate Marshall was an emerging talent with London’s Met Police – until a near fatal encounter with a serial killer ended her career. When a copycat killer starts to mimic the work of the man who nearly killed her, she is inexorably drawn back into the investigative front line. Nine Elms is published by Sphere, is out now as a Kindle and in hardback

Bryndza already has an established audience for his Detective Erika Foster series, and he now introduces another female copper to the crime scene. Fifteen years earlier, Kate Marshall was an emerging talent with London’s Met Police – until a near fatal encounter with a serial killer ended her career. When a copycat killer starts to mimic the work of the man who nearly killed her, she is inexorably drawn back into the investigative front line. Nine Elms is published by Sphere, is out now as a Kindle and in hardback This came out in Kindle back in the summer of this year, but now readers who like the feel of a printed book in their hands get to join the party. They say there is nothing as ferocious, either in the animal world or the human sphere, as a mother protecting her young. A woman has to look on helplessly as the man accused of attacking her daughter is set free. Tess’s quest for justice, however, plunges those she loves most into a cauldron bubbling with hatred and danger. Out on 26th December,

This came out in Kindle back in the summer of this year, but now readers who like the feel of a printed book in their hands get to join the party. They say there is nothing as ferocious, either in the animal world or the human sphere, as a mother protecting her young. A woman has to look on helplessly as the man accused of attacking her daughter is set free. Tess’s quest for justice, however, plunges those she loves most into a cauldron bubbling with hatred and danger. Out on 26th December,  It may well be that someone, somewhere, has written a cosy ‘feet up in front of the fire’ crime novel set in Belfast. If they have, it has passed me by, as the streets of that city, their very stones stained to the core with the ancient bitterness of sectarian violence, always seem to provide a natural backdrop for gritty thrillers. When London Detective Inspector Owen Sheen returns to his home turf to set up a special crime unit, he is sucked into an investigation which, in double quick time, becomes political – and personal. This, Gary Donnelly’s debut thriller will be out on 20th February and is

It may well be that someone, somewhere, has written a cosy ‘feet up in front of the fire’ crime novel set in Belfast. If they have, it has passed me by, as the streets of that city, their very stones stained to the core with the ancient bitterness of sectarian violence, always seem to provide a natural backdrop for gritty thrillers. When London Detective Inspector Owen Sheen returns to his home turf to set up a special crime unit, he is sucked into an investigation which, in double quick time, becomes political – and personal. This, Gary Donnelly’s debut thriller will be out on 20th February and is  Set in a 1960s mental hospital with the ominous name of Black Roding, this is the story of an idealistic and progressive young psychiatrist, Ruth, whose ideas for a more enlightened regime find no favour with the suspicious staff. Becoming rather too close to a complex and troubled inmate of Black Rodings, Ruth’s determination to find new ways of doing things draws her into a horrifying vortex of hidden crimes and shocking revelations. Published by Matador,

Set in a 1960s mental hospital with the ominous name of Black Roding, this is the story of an idealistic and progressive young psychiatrist, Ruth, whose ideas for a more enlightened regime find no favour with the suspicious staff. Becoming rather too close to a complex and troubled inmate of Black Rodings, Ruth’s determination to find new ways of doing things draws her into a horrifying vortex of hidden crimes and shocking revelations. Published by Matador,  Lesley Kara captured the potentially poisonous dynamic of small town gossip in her 2018 thriller

Lesley Kara captured the potentially poisonous dynamic of small town gossip in her 2018 thriller

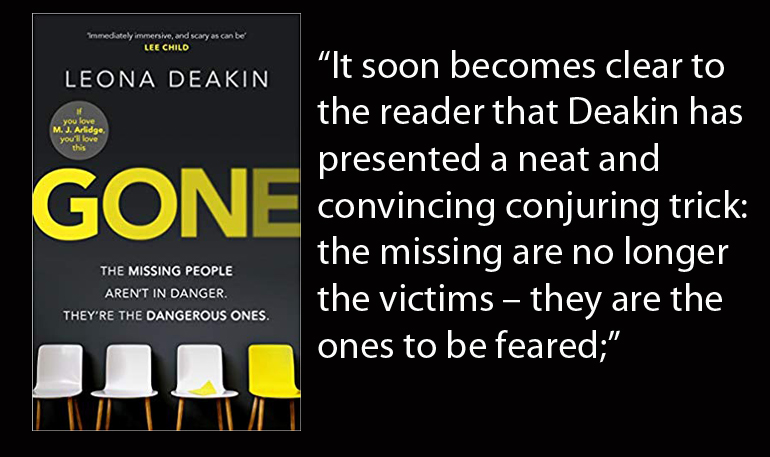

Jameson’s sister Claire has, for some time, fulfilled a mixed role of aunt, mother and babysitter to a teenage girl called Jane. Jane’s mother Lana, is a single mum, loving but chaotic, perhaps suffering from PTSD after several tours in conflict zones when she was a soldier in the army. Now she has disappeared, leaving Jane with no money for food or rent. Knowing of her mum’s fragile mental state. Jane was not initially alarmed, but when she began to investigate, after receiving no help from the police, she made several disturbing discoveries.

Lana disappeared on her birthday. Immediately before her disappearance she had received a mysterious card inviting her to play a game. The beautifully presented card bore the words, elegantly embossed in silver on cream:

Jameson’s sister Claire has, for some time, fulfilled a mixed role of aunt, mother and babysitter to a teenage girl called Jane. Jane’s mother Lana, is a single mum, loving but chaotic, perhaps suffering from PTSD after several tours in conflict zones when she was a soldier in the army. Now she has disappeared, leaving Jane with no money for food or rent. Knowing of her mum’s fragile mental state. Jane was not initially alarmed, but when she began to investigate, after receiving no help from the police, she made several disturbing discoveries.

Lana disappeared on her birthday. Immediately before her disappearance she had received a mysterious card inviting her to play a game. The beautifully presented card bore the words, elegantly embossed in silver on cream: Leona Deakin’s own experience and training in psychology gives this novel a framework of authenticity to which the more fanciful parts of the narrative can cling. It soon becomes clear to the reader that Deakin has presented a neat and convincing conjuring trick: the missing are no longer the victims – they are the ones to be feared; those left behind have become the prey.

The relationship between Bloom and Jameson is intriguing. It reminded me of the unresolved tension and undeclared love between Val McDermid’s doomed lovers Tony Hill and Carol Jordan. We are left to decide for ourselves what Augusta Bloom looks like; Deakin (right) suggests that she might be rather dowdy, an academic in flat shoes. She is certainly razor sharp mentally, however, and she plays a devastating human chess game with the organisation behind the birthday card disappearances.

Leona Deakin’s own experience and training in psychology gives this novel a framework of authenticity to which the more fanciful parts of the narrative can cling. It soon becomes clear to the reader that Deakin has presented a neat and convincing conjuring trick: the missing are no longer the victims – they are the ones to be feared; those left behind have become the prey.

The relationship between Bloom and Jameson is intriguing. It reminded me of the unresolved tension and undeclared love between Val McDermid’s doomed lovers Tony Hill and Carol Jordan. We are left to decide for ourselves what Augusta Bloom looks like; Deakin (right) suggests that she might be rather dowdy, an academic in flat shoes. She is certainly razor sharp mentally, however, and she plays a devastating human chess game with the organisation behind the birthday card disappearances.