istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle.

istorical crime fiction is all the more accessible when the history is recent enough for readers such as I to recognise it as authentic, and give a nostalgic sigh when some piece of popular consumer ephemera – a brand of chocolate, a radio programme or a make of car – crops up in the narrative. Colin Crampton may possibly be the autobiographical alter ego of author Peter Bartram, himself a distinguished and experienced journalist who remembers the deafening sound of the printing presses, the smell of ink, the jangle of telephones in the press room, the scratch of a pen on the paper of a notebook, and the overiding miasma of Woodbines and Senior Service drifting on the air. The Poker Game Mystery is the latest episode in the eventful career of Colin Crampton, crime reporter for the Brighton Evening Chronicle.

One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master.

One of the many joys of the Colin Crampton novels is that Peter Bartram usually manages to set the tales against actual circumstances appropriate to the period and, sometimes, we have a very thinly disguised version of a real person. In this case, we meet an outlandish minor aristocrat, heir to daddy’s millions but, more luridly, a fancier of young women. He collects them, rather like a lepidopterist collects butterflies, but rather than sticking his prizes into a display case with a pin, he keeps his young lovelies in cottages the length and breadth of the extensive estate, and has managed to organise one for each day of the week. For the life of me, I can’t think of whom Peter might have as his template for this roué, but I expect it will come to me in the middle of the night, rather like Ms Monday and the others do to their lord and master.

hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her.

hen the body of a widely disliked local bouncer is found – his face a rictus of horror and agony – with a suspiciously large sum of used notes beside him, Crampton is sucked into a case which involves a shadowy WW2 home defence unit known as The Scallywags. Crampton discovers that they were a strange combination of Dad’s Army and the SAS – trained to wreak havoc on the Germans should they ever succeed in invading Britain. To enliven matters further, the aforementioned noble Lothario becomes the new owner of The Chronicle on the death of his father, but then promptly signs away the paper as a stake in a losing card game, this threatening the existence of The Chronicle – and those who sail in her.

ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly.

ided by his feisty (and rather beautiful) Australian girlfriend, Crampton is up to his neck in a sea of trouble involving, among other things, dead bodies, wartime gold bullion, a predatory newspaper baron, and the arcane skill of doctoring a set of playing cards. It’s wonderful stuff – not just a crime caper, but another fine novel from a writer who wears his learning lightly.

Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

Colin Crampton’s Brighton is slightly down at heel but all the more charming for not yet having succumbed to the deadening hand which has now made it the world capital of all things green, ‘woke’, diverse and inclusive. There are still saucy postcards to be bought at the sea-front newsagent, and incorrect jokes to be delivered by Brylcreemed comedians in faded variety halls. Peter Bartram (right) has set the bar very high with his previous Crampton novels but he just gets better and better, and The Poker Game Mystery clears that bar with loads to spare. We even have a finale worthy of Indiana Jones, albeit in a murky tunnel somewhere in Sussex rather than in some more exotic location. A word of warning. If the words Atrax Robustus make you feel queasy, then you might need someone to mop your fearful brow while you read the final pages. Clue – not all of Australia’s exports are as cuddly as Crampton’s gorgeous girlfriend, Shirley Goldsmith.

The Poker Game Mystery is published by The Bartram Partnership

and is out now.

For further enjoyment of all things Colin Crampton

and Peter Bartram click the image below

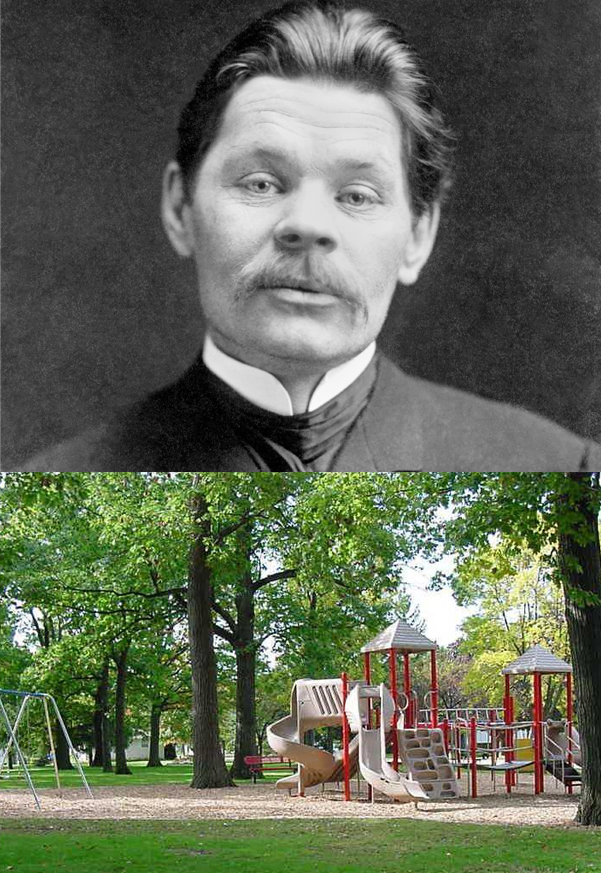

Guy Portman (left) introduced us to Dyson Devereux in Necropolis (2014). I gave it 5* when writing for another review site, and I’ll include a link to that at the end of this post. Dyson was Head of Burials and Cemeteries in a fictional Essex town, and a rather individual young man. He is narcissistic, punctilious, cultured and, outwardly polite and thoughtful, but with an anarchic mind and a terrible propensity for extreme violence. The book both horrified and fascinated me but made me laugh out loud. Dyson Devereux was a Home Counties version of Patrick Bateman and his antics allowed Portman to poke savage fun at all kinds of modern social idiocies.

Guy Portman (left) introduced us to Dyson Devereux in Necropolis (2014). I gave it 5* when writing for another review site, and I’ll include a link to that at the end of this post. Dyson was Head of Burials and Cemeteries in a fictional Essex town, and a rather individual young man. He is narcissistic, punctilious, cultured and, outwardly polite and thoughtful, but with an anarchic mind and a terrible propensity for extreme violence. The book both horrified and fascinated me but made me laugh out loud. Dyson Devereux was a Home Counties version of Patrick Bateman and his antics allowed Portman to poke savage fun at all kinds of modern social idiocies. When he finally has his day in court, Dyson scorns the efforts of his lack-lustre lawyer and relies on his own charm and nobility of bearing to convince the court that he is an innocent man. He escapes the clinging arms of Alegra and returns to England without delay, anxious to be reunited with something from which separation has become a cruel burden. A loving family? A childhood sweetheart? The clear skies and careless rapture of an English summer day? No. A tin box containing several memento mori of his previous victims. Little oddments that he can sniff, fondle and treasure. Little bits of people who have had the temerity to upset him, and have paid the price.

When he finally has his day in court, Dyson scorns the efforts of his lack-lustre lawyer and relies on his own charm and nobility of bearing to convince the court that he is an innocent man. He escapes the clinging arms of Alegra and returns to England without delay, anxious to be reunited with something from which separation has become a cruel burden. A loving family? A childhood sweetheart? The clear skies and careless rapture of an English summer day? No. A tin box containing several memento mori of his previous victims. Little oddments that he can sniff, fondle and treasure. Little bits of people who have had the temerity to upset him, and have paid the price.

eaders of a Simon Kernick thriller should know by now what they are getting. There will be violence a-plenty, betrayal, corrupt cops, unscrupulous politicians, improbable escapes from certain death and a narrative style which grips the reader from start to finish. Like many popular writers he has separate series on the go, but Kernick isn’t averse to cross-referencing characters. By my reckoning, Die Alone is the eleventh book to feature the abrasive and resourceful Tina Boyd – once a copper but, in this novel a private investigator. The main man I Die Alone is another copper – Ray Mason. He first featured in The Witness (2016). Then came The Bone Field (2017) and The Hanged Man (2018) but with Tina Boyd – and her former lover Mike Bolt – in attendance.

eaders of a Simon Kernick thriller should know by now what they are getting. There will be violence a-plenty, betrayal, corrupt cops, unscrupulous politicians, improbable escapes from certain death and a narrative style which grips the reader from start to finish. Like many popular writers he has separate series on the go, but Kernick isn’t averse to cross-referencing characters. By my reckoning, Die Alone is the eleventh book to feature the abrasive and resourceful Tina Boyd – once a copper but, in this novel a private investigator. The main man I Die Alone is another copper – Ray Mason. He first featured in The Witness (2016). Then came The Bone Field (2017) and The Hanged Man (2018) but with Tina Boyd – and her former lover Mike Bolt – in attendance. We start with Mason in the Vulnerable Prisoner wing at a high security British prison. He is serving life sentences for the killing of two deeply unpleasant characters in the course of his duties. The deaths were judged not to be judicial, and so Mason inhabits a world shared with paedophiles, rapists, child pornographers – and disgraced coppers. When he is injured on the periphery of a prison riot, he is taken off to hospital in a supposedly secure van, which is then hijacked – the target being Mason himself. He is taken to what seems to be some kind of safe house run on government lines and, after being well fed and housed for a couple of days, he is given an ultimatum by the masked official who is in charge of things – carry out a hit on a Very Important target. He is left in no doubt as to what will happen if he refuses, but he takes little persuading, as the intended victim is someone whose life Mason would have little compunction in ending.

We start with Mason in the Vulnerable Prisoner wing at a high security British prison. He is serving life sentences for the killing of two deeply unpleasant characters in the course of his duties. The deaths were judged not to be judicial, and so Mason inhabits a world shared with paedophiles, rapists, child pornographers – and disgraced coppers. When he is injured on the periphery of a prison riot, he is taken off to hospital in a supposedly secure van, which is then hijacked – the target being Mason himself. He is taken to what seems to be some kind of safe house run on government lines and, after being well fed and housed for a couple of days, he is given an ultimatum by the masked official who is in charge of things – carry out a hit on a Very Important target. He is left in no doubt as to what will happen if he refuses, but he takes little persuading, as the intended victim is someone whose life Mason would have little compunction in ending. y now Kernick has introduced us to the repulsive Alastair Sheridan, a millionaire former hedge fund manager who has found his niche in politics and is regarded as everyone’s favourite to reach the top because of his affable style, movie star good looks and undoubted charisma. What the adoring public, and a bevy of fellow MPs who are about to support his leadership don’t now is that Sheridan is a sadistic sexual killer with links to organised crime and some of the most evil people in Europe.

y now Kernick has introduced us to the repulsive Alastair Sheridan, a millionaire former hedge fund manager who has found his niche in politics and is regarded as everyone’s favourite to reach the top because of his affable style, movie star good looks and undoubted charisma. What the adoring public, and a bevy of fellow MPs who are about to support his leadership don’t now is that Sheridan is a sadistic sexual killer with links to organised crime and some of the most evil people in Europe. ecuring the help of former colleague Tina Boyd gets Mason out of one scrape, but as he avoids the clutches of one set of villains, the next shootout or escape in the boot of someone’s car is just around the corner, with the action ranging from oily Tottenham car workshops, to rural Essex and then via Brittany to the bloodstained hills surrounding Sarajevo.

ecuring the help of former colleague Tina Boyd gets Mason out of one scrape, but as he avoids the clutches of one set of villains, the next shootout or escape in the boot of someone’s car is just around the corner, with the action ranging from oily Tottenham car workshops, to rural Essex and then via Brittany to the bloodstained hills surrounding Sarajevo.

It is 1921. In Britain, dignified war memorials, paid for by public subscription, are beginning to be dedicated. In France and Belgium most cities and towns within artillery range of the Old Front Line stand in ruins, while villages are usually reduced to random piles of shattered bricks. The dead are everywhere. In places where the living have yet to re-establish themselves there are crosses. Thousands upon thousands of simple wooden crosses, distinguished one from the other with a basic aluminium strip, letters stamped on it and pinned to the wood. A former officer, now a worker for what would become the Commonwealth War Graves Commission explains his mission:

It is 1921. In Britain, dignified war memorials, paid for by public subscription, are beginning to be dedicated. In France and Belgium most cities and towns within artillery range of the Old Front Line stand in ruins, while villages are usually reduced to random piles of shattered bricks. The dead are everywhere. In places where the living have yet to re-establish themselves there are crosses. Thousands upon thousands of simple wooden crosses, distinguished one from the other with a basic aluminium strip, letters stamped on it and pinned to the wood. A former officer, now a worker for what would become the Commonwealth War Graves Commission explains his mission: arry Blythe makes his living meeting a macabre but necessary demand. He travels the shattered countryside, on commission from relatives, taking photographs of the crosses, or the places of which dead men spoke in their letters home. There were three Blythe brothers, Will, Harry and Francis. Only Harry has survived the conflict. As in other silent houses across the country, mothers did what mothers always do – adjust and try to get on with things:

arry Blythe makes his living meeting a macabre but necessary demand. He travels the shattered countryside, on commission from relatives, taking photographs of the crosses, or the places of which dead men spoke in their letters home. There were three Blythe brothers, Will, Harry and Francis. Only Harry has survived the conflict. As in other silent houses across the country, mothers did what mothers always do – adjust and try to get on with things:

ilfred Owen wrote, concerning his work, “The Poetry is in the pity.” Caroline Scott echoes this message. Such was the disconnect between life in the trenches and home that, for many men, returning on leave was not the joyous temporary reprieve from hell that we might imagine:

ilfred Owen wrote, concerning his work, “The Poetry is in the pity.” Caroline Scott echoes this message. Such was the disconnect between life in the trenches and home that, for many men, returning on leave was not the joyous temporary reprieve from hell that we might imagine:

Atlee Pine has anger management issues, and A Minute To Midnight begins as she is put on gardening leave for kicking the you-know-what out of a child rapist. She decides to use this enforced leisure time in another attempt to find out what happened on the fateful night when her sister was abducted and she was left with a fractured skull. Accompanied by her admin assistant Carol Blum, she revisits the scene of the trauma, the modest town of Andersonville, Georgia. Tumbleweed is the word that first comes to mind about Andersonville, but it scrapes a living from tourists wishing to visit the remains of the Confederate prisoner of war camp which, in its mere fourteen months of existence, caged over thirty thousand Union prisoners of whom nearly thirteen thousand were to perish from wounds, disease and malnutrition.

Atlee Pine has anger management issues, and A Minute To Midnight begins as she is put on gardening leave for kicking the you-know-what out of a child rapist. She decides to use this enforced leisure time in another attempt to find out what happened on the fateful night when her sister was abducted and she was left with a fractured skull. Accompanied by her admin assistant Carol Blum, she revisits the scene of the trauma, the modest town of Andersonville, Georgia. Tumbleweed is the word that first comes to mind about Andersonville, but it scrapes a living from tourists wishing to visit the remains of the Confederate prisoner of war camp which, in its mere fourteen months of existence, caged over thirty thousand Union prisoners of whom nearly thirteen thousand were to perish from wounds, disease and malnutrition. A series of apparently motiveless murders in Andersonville diverts Pine from the search for her own personal truth, and she is soon enlisted to help the understaffed and under-resourced local cops. The first murder victims – a man and a woman – are killed elsewhere but then delivered to Andersonville bedecked as bride and groom respectively. When it turns out that they were both involved in the porn industry, what first appears to be a significant lead runs into a brick wall.

A series of apparently motiveless murders in Andersonville diverts Pine from the search for her own personal truth, and she is soon enlisted to help the understaffed and under-resourced local cops. The first murder victims – a man and a woman – are killed elsewhere but then delivered to Andersonville bedecked as bride and groom respectively. When it turns out that they were both involved in the porn industry, what first appears to be a significant lead runs into a brick wall.