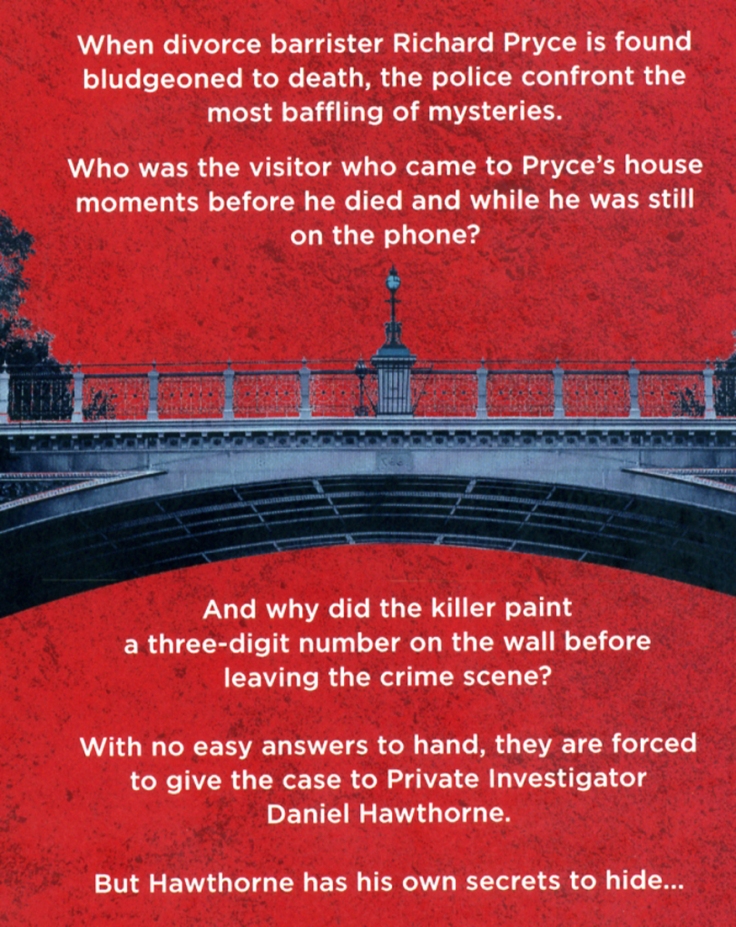

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the first book in this series, The Word Is Murder (and you can read my review here) you need to know that Anthony Horowitz has created a quite delightful literary conceit, and it is this: the story is narrated by Anthony Horowitz, as himself, and along the way we get to meet other real people in his life, such as his wife, his literary agent, and even some of the actors in his Foyle’s War series. The principal fictional character is an ex Met Police officer called Daniel Hawthorne, who was drummed out of the service for misconduct, but now operates as a private investigator, paid by the day by his former employers to work on difficult cases. Hawthorne has persuaded Horowitz to be Boswell to his Johnson and to write up the investigations as crime fiction.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the first book in this series, The Word Is Murder (and you can read my review here) you need to know that Anthony Horowitz has created a quite delightful literary conceit, and it is this: the story is narrated by Anthony Horowitz, as himself, and along the way we get to meet other real people in his life, such as his wife, his literary agent, and even some of the actors in his Foyle’s War series. The principal fictional character is an ex Met Police officer called Daniel Hawthorne, who was drummed out of the service for misconduct, but now operates as a private investigator, paid by the day by his former employers to work on difficult cases. Hawthorne has persuaded Horowitz to be Boswell to his Johnson and to write up the investigations as crime fiction.

Hawthorne is an intriguing character. He is probably somewhere on the autistic spectrum, lives alone, and has few social graces, His powers of deduction and observation are, however, remarkably sound. He immediately sees through the statement one witness has just given:

“The MG was right in front of us. Hawthorn pointed with the hand holding the cigarette.

‘There’s no way that’s just driven down from Essex of Suffolk, or anywhere near the coast.’

‘How do you know?’

‘The house he showed us in that photograph didn’t have a garage and there’s no way this car has been sitting by the seaside for three days. There’s no seagull shit. And there’s no dead insects on the windscreen either. Your telling me he’s driven a hundred miles down the A12 and he hasn’t hit a single midge or fly?’”

The case which has forced the police to seek Hawthorne’s help concerns a rich divorce lawyer who has been found battered to death in his luxurious house on the edge of London’s Hampstead Heath. For a decade or more Richard Pryce has been the go-to man for wealthy people who have had enough of their wives or husbands and want a divorce, but more particularly a divorce which will leave Pryce’s clients with as much of the family loot as possible. So, it is inevitable that while Pryce is adored by some, he is bitterly hated by others, and thus there are one or two obvious initial suspects. First among these is a rather aloof literary author whose determination to conflate America’s 1940s nuclear strategy with gender politics has won her many admirers of a certain sort. Her expensively produced collection of pretentiously profound haikus (is there any other kind?) has also made her much in demand at soirées in upmarket bookshops.

Then there is Pryce’s art dealer husband who, Hawthorne soon discovers, has been ‘playing away’ with the svelte young Iranian man who is front-of-house in his so, so discreet gallery. Has his affair been rumbled? Was Pryce about to cut him out of his will? The most unlikely connection, however, relates to Pryce’s younger self when he and two university buddies were enthusiastic cavers. Did a tragedy years earlier, 80 metres beneath the Yorkshire Dales, set in train a slow but remorseless search for revenge?

The abundance of questions will give away the fact that this is a tremendous whodunnit. Horowitz (right) tugs his forelock in the direction of the great masters of the genre and, while we don’t quite have the denouement in the library, we have a bewildering trail of red herrings before the dazzling final exposition. But there is more. Much, much more. Horowitz’s portrayal of himself is beautifully done. I have only once brushed shoulders with the gentleman at a publisher’s bash, so I don’t know if the self-effacing tone is accurate, but it is warm and convincing. More than once he finds himself the earnest but dull Watson to Hawthorne’s ridiculously clever Holmes.

The abundance of questions will give away the fact that this is a tremendous whodunnit. Horowitz (right) tugs his forelock in the direction of the great masters of the genre and, while we don’t quite have the denouement in the library, we have a bewildering trail of red herrings before the dazzling final exposition. But there is more. Much, much more. Horowitz’s portrayal of himself is beautifully done. I have only once brushed shoulders with the gentleman at a publisher’s bash, so I don’t know if the self-effacing tone is accurate, but it is warm and convincing. More than once he finds himself the earnest but dull Watson to Hawthorne’s ridiculously clever Holmes.

Horowitz is, I suspect, too polite to be cruel to fellow writers, but he cannot resist a dig at earnest feminist authors who treat every moment of history as if it were a glaring example of man’s inhumanity to women. Trash fiction does not escape, either, and when his fictional self reads a page from the latest sub-Game of Thrones swords and sorcery shocker, it is horribly accurate. Above all, though, this is a classic 24 hour novel. You start reading, you dart off to do something like pick up the kids, or turn on the oven. Back you come to the book, and before you know it, you are 200 pages in. Time flies by, and then bang! It’s finished. You know who the killer is, but you just wish you could start the book all over again. It really is that good. Published by Century, The Sentence Is Death is out on 1st November.

James Oswald’s Tony McLean has not met with a Reichenbach Falls accident, but at the end of

James Oswald’s Tony McLean has not met with a Reichenbach Falls accident, but at the end of

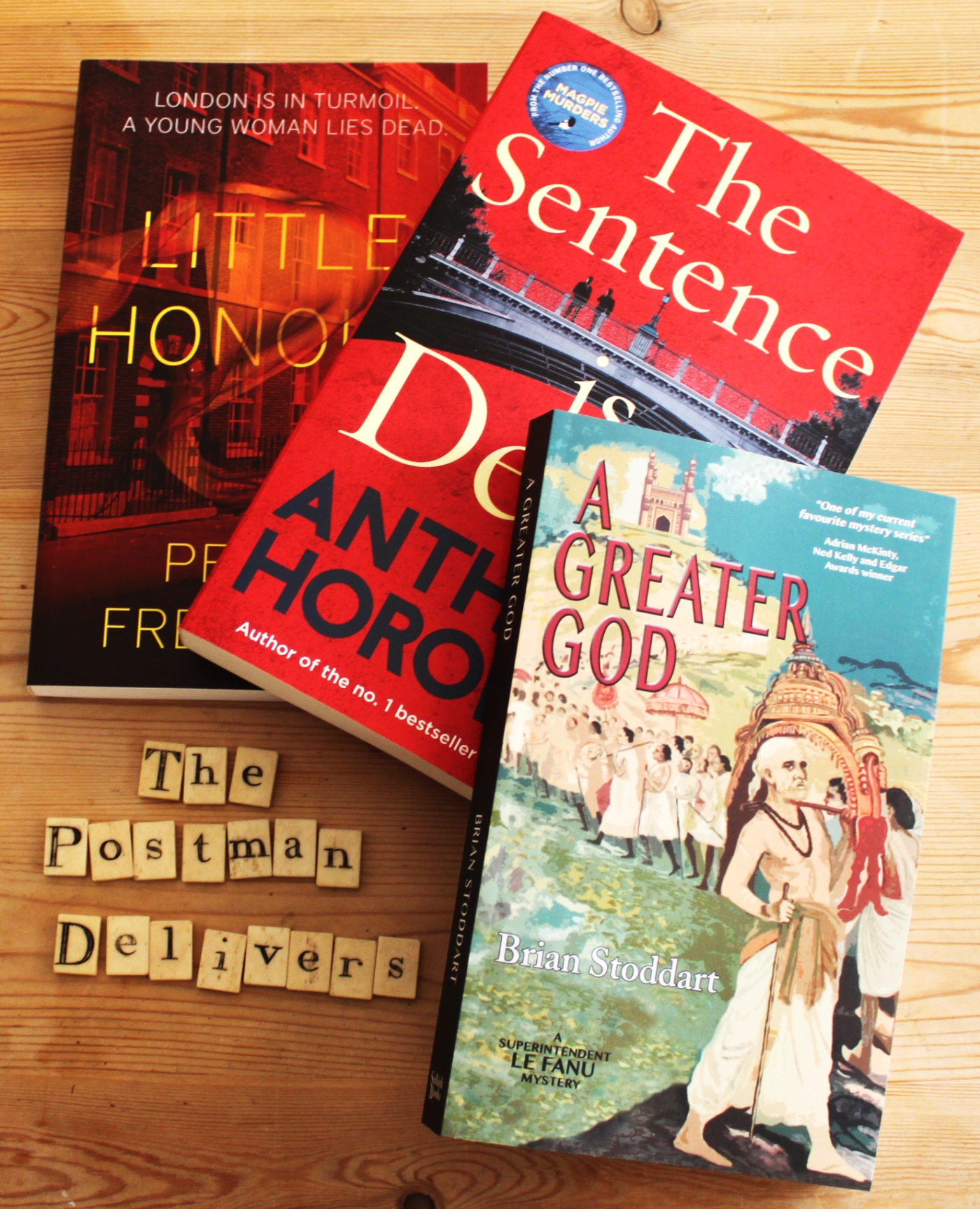

Penny Freedman (left) has been many things; a teacher, theatre critic, actor, director, counsellor and mother, but she also writes intriguing crime fiction. Her heroine Gina Gray has appeared in previous novels including Weep A While Longer and Drown My Books, but now we learn more about her granddaughter Freda, in a murder mystery which encompasses hate crime in a post-referendum London, the arcane world of legal chambers in Grey’s Inn and – for good measure – a missing dog. Available now, Little Honour is published by

Penny Freedman (left) has been many things; a teacher, theatre critic, actor, director, counsellor and mother, but she also writes intriguing crime fiction. Her heroine Gina Gray has appeared in previous novels including Weep A While Longer and Drown My Books, but now we learn more about her granddaughter Freda, in a murder mystery which encompasses hate crime in a post-referendum London, the arcane world of legal chambers in Grey’s Inn and – for good measure – a missing dog. Available now, Little Honour is published by  Anthony Horowitz has a glittering array of successes on his CV, including reincarnations of both Sherlock Holmes and James Bond , Foyle’s War, and the Alex Rider series. This is the latest book in a more recent series centred on a London private investigator, Daniel Hawthorne. When a high profile lawyer best-known for handling celebrity divorces is found dead in his luxury home overlooking Hampstead Heath, the police investigation gets nowhere, and they reluctantly bring in former copper Hawthorne. Hawthorne’s usual cool detachment from the case is disturbed when he becomes personally involved, with his own life very much on the line. The Sentence Is Death will be on the shelves on 1st November and is

Anthony Horowitz has a glittering array of successes on his CV, including reincarnations of both Sherlock Holmes and James Bond , Foyle’s War, and the Alex Rider series. This is the latest book in a more recent series centred on a London private investigator, Daniel Hawthorne. When a high profile lawyer best-known for handling celebrity divorces is found dead in his luxury home overlooking Hampstead Heath, the police investigation gets nowhere, and they reluctantly bring in former copper Hawthorne. Hawthorne’s usual cool detachment from the case is disturbed when he becomes personally involved, with his own life very much on the line. The Sentence Is Death will be on the shelves on 1st November and is  One of my favourite historical policemen returns in the latest episode in the eventful life of Superintendent Chris Le Fanu. We are in Madras (Chennai) in the 1920s, and while the British grip on India is becoming weaker and weaker, there is still police work to be done. The city is blighted by a wave of violent clashes between Muslims, revolutionaries, and the blundering attempts by Le Fanu’s boss to restore order. Expect a brilliant narrative, impeccable historical background and authentic dialogue. A Greater God is published by Selkirk Books and will be

One of my favourite historical policemen returns in the latest episode in the eventful life of Superintendent Chris Le Fanu. We are in Madras (Chennai) in the 1920s, and while the British grip on India is becoming weaker and weaker, there is still police work to be done. The city is blighted by a wave of violent clashes between Muslims, revolutionaries, and the blundering attempts by Le Fanu’s boss to restore order. Expect a brilliant narrative, impeccable historical background and authentic dialogue. A Greater God is published by Selkirk Books and will be

Chief Inspector Armand Gamache

Chief Inspector Armand Gamache  Some ex-military men find that civilian life is hard to deal with, but Paul Stafford is coping well. He has used his retirement pot to start a small recycling business and everything in the scrapyard seems to be rosy, until he wins a lucrative contract to run a further five sites. What should be a business triumph turns into a nightmare for Stafford when he realises that his new sites have been previously used by a powerful criminal organisation, and the bad guys do not take kindly to their work being interrupted. Murder and violence come as second nature to them, and when his own employees begin to feel the full clout of the gangsters, Stafford must stand and fight – both for them and his own integrity.

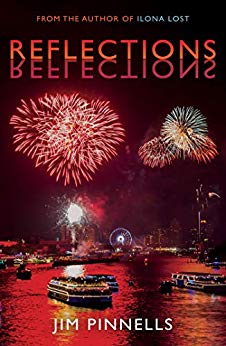

Some ex-military men find that civilian life is hard to deal with, but Paul Stafford is coping well. He has used his retirement pot to start a small recycling business and everything in the scrapyard seems to be rosy, until he wins a lucrative contract to run a further five sites. What should be a business triumph turns into a nightmare for Stafford when he realises that his new sites have been previously used by a powerful criminal organisation, and the bad guys do not take kindly to their work being interrupted. Murder and violence come as second nature to them, and when his own employees begin to feel the full clout of the gangsters, Stafford must stand and fight – both for them and his own integrity.  Jim Pinnells is an international project manager who has worked in such diverse concerns as the oil industry, military hardware, renewable technology and national security. His knowledge of Thailand stems from a spell there working for the UN, and Reflections is set in Bangkok, where a poignant human drama is played out against a backdrop of one of the world’s most secretive criminal enterprises – the trade in human blood. Ed and Diana seem to have it all – beauty, talent and love for each other – but when their first child is born irreparably brain damaged, their world fall apart. Ed pursues the heartbroken to Diana to Thailand but a case of mistaken identity plunges him into a nightmare world of violence, kidnap and espionage. Reflections is published by Troubador

Jim Pinnells is an international project manager who has worked in such diverse concerns as the oil industry, military hardware, renewable technology and national security. His knowledge of Thailand stems from a spell there working for the UN, and Reflections is set in Bangkok, where a poignant human drama is played out against a backdrop of one of the world’s most secretive criminal enterprises – the trade in human blood. Ed and Diana seem to have it all – beauty, talent and love for each other – but when their first child is born irreparably brain damaged, their world fall apart. Ed pursues the heartbroken to Diana to Thailand but a case of mistaken identity plunges him into a nightmare world of violence, kidnap and espionage. Reflections is published by Troubador

Coming across a very, very good book by an author one has never encountered before and then realising that she has been around for a while is a shock to the system, and if the downside is that the experience further highlights one’s own ignorance, then the blessing is that as a reviewer and blogger, there is something new to shout about. Jane A Adams made her debut with The Greenway back in 1995, and has been writing crime fiction ever since, notably with four-well established mystery series featuring Mike Croft, Ray Flowers, Naomi Blake and Rina Martin. She began the saga of London coppers Henry Johnstone and Micky Hitchens in 2016, with The Murder Book. Their latest case is Kith and Kin.

Coming across a very, very good book by an author one has never encountered before and then realising that she has been around for a while is a shock to the system, and if the downside is that the experience further highlights one’s own ignorance, then the blessing is that as a reviewer and blogger, there is something new to shout about. Jane A Adams made her debut with The Greenway back in 1995, and has been writing crime fiction ever since, notably with four-well established mystery series featuring Mike Croft, Ray Flowers, Naomi Blake and Rina Martin. She began the saga of London coppers Henry Johnstone and Micky Hitchens in 2016, with The Murder Book. Their latest case is Kith and Kin. The period is set to perfection, and Adams (right) skilfully combines past, present and future. The past? There can scarcely have been a man, woman or child who escaped the malign effects of what politicians swore would be the war to end wars. The present? 1928 saw devastating flooding on the banks of the River Thames, a book called Decline And Fall was published, and in Beckenham, not a million miles away from where this novel plays out, Robert ‘Bob’ Monkhouse was born. The future? Johnstone’s sister, who has married into money, has a head on her shoulders, and senses that in the financial world, a dam is about to break – with devastating effects.

The period is set to perfection, and Adams (right) skilfully combines past, present and future. The past? There can scarcely have been a man, woman or child who escaped the malign effects of what politicians swore would be the war to end wars. The present? 1928 saw devastating flooding on the banks of the River Thames, a book called Decline And Fall was published, and in Beckenham, not a million miles away from where this novel plays out, Robert ‘Bob’ Monkhouse was born. The future? Johnstone’s sister, who has married into money, has a head on her shoulders, and senses that in the financial world, a dam is about to break – with devastating effects.

The Tony McLean novels have established James Oswald as one of the stars in the current British crime fiction firmament. We reviewed the most recent,

The Tony McLean novels have established James Oswald as one of the stars in the current British crime fiction firmament. We reviewed the most recent,

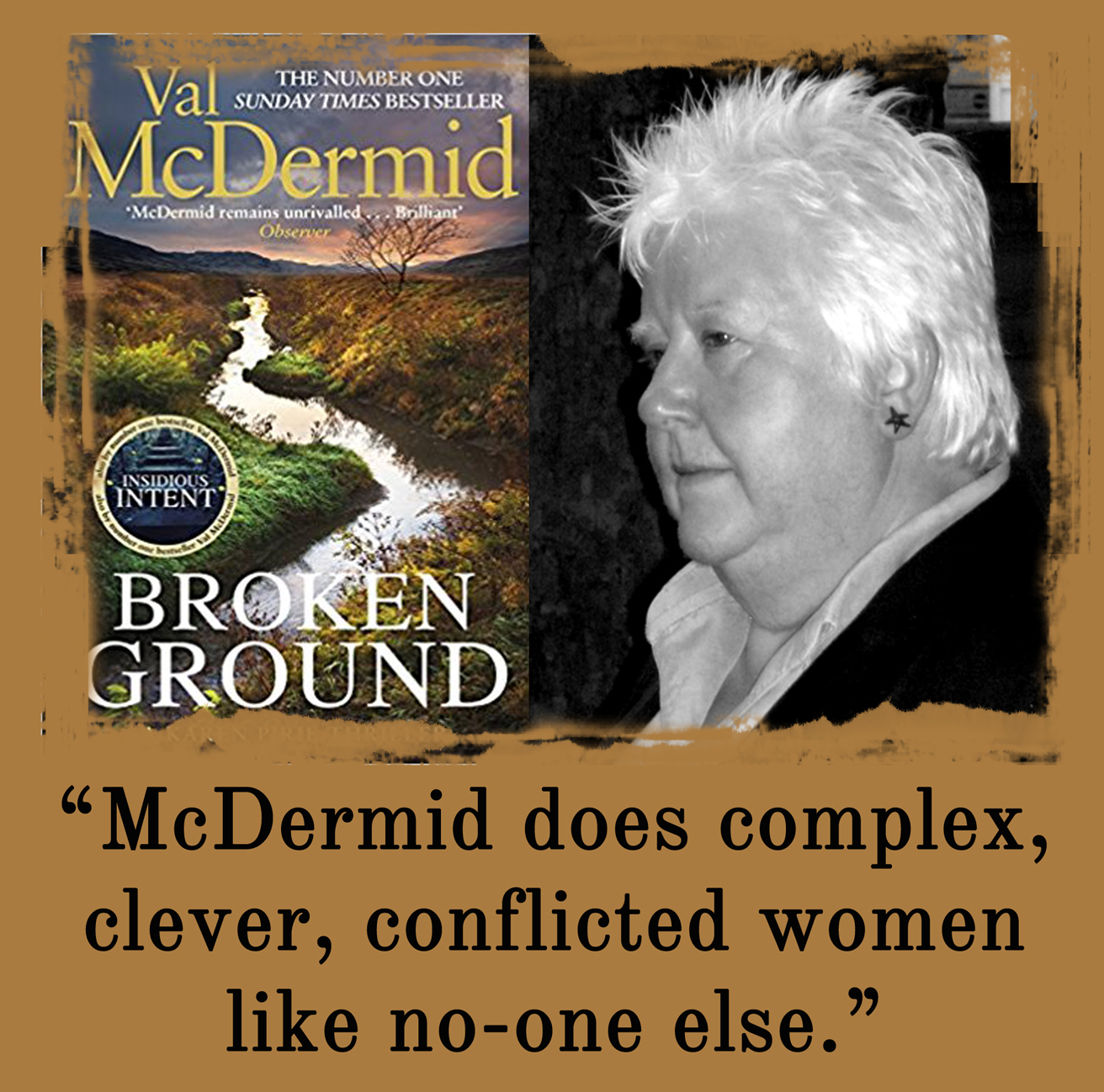

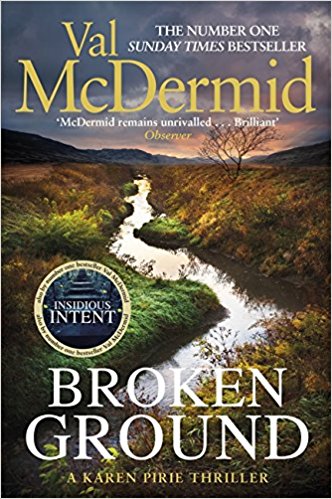

The Body In The Bog is a nicely alliterative strapline normally used to liven up reports of archaeologists discovering some centuries-old corpse in a watery peat grave. The deaths of these poor souls does not usually involve an investigation by the local police force, but as Val McDermid relates, when the preserved remains are wearing expensive trainers, it doesn’t take the tenant of 221B Baker Street to deduce that the chap was not executed as part of some arcane tribal ritual back in the tenth century.

The Body In The Bog is a nicely alliterative strapline normally used to liven up reports of archaeologists discovering some centuries-old corpse in a watery peat grave. The deaths of these poor souls does not usually involve an investigation by the local police force, but as Val McDermid relates, when the preserved remains are wearing expensive trainers, it doesn’t take the tenant of 221B Baker Street to deduce that the chap was not executed as part of some arcane tribal ritual back in the tenth century. If music halls were still in vogue, McDermid would be the dextrous juggler, the jongleur who defies gravity by keeping several plot lines spinning in the air; spinning, but always under her control. There is the Nike bog body, a domestic spat which ends in savagery, a cold-case rape investigation which ends in a very contemporary tragedy, and an Assistant Chief Constable who is more concerned about her perfectly groomed press conferences that solving crime. They say that the moon has a dark side, and so does Edinburgh: McDermid (right) takes us on a guided tour through its majestic architectural and natural scenery, but does not neglect to pull away the undertaker’s sheet to reveal the squalid back alleys and passageways which lurk behind the grand Georgian facades. We slip past the modest security and peep through a crack in the door at a meeting in one of the grander rooms of Bute House, the official residence of Scotland’s First Minister, even getting a glimpse of the good lady herself, although McDermid is far too discreet to reveal if she approves or disapproves of Ms Sturgeon.

If music halls were still in vogue, McDermid would be the dextrous juggler, the jongleur who defies gravity by keeping several plot lines spinning in the air; spinning, but always under her control. There is the Nike bog body, a domestic spat which ends in savagery, a cold-case rape investigation which ends in a very contemporary tragedy, and an Assistant Chief Constable who is more concerned about her perfectly groomed press conferences that solving crime. They say that the moon has a dark side, and so does Edinburgh: McDermid (right) takes us on a guided tour through its majestic architectural and natural scenery, but does not neglect to pull away the undertaker’s sheet to reveal the squalid back alleys and passageways which lurk behind the grand Georgian facades. We slip past the modest security and peep through a crack in the door at a meeting in one of the grander rooms of Bute House, the official residence of Scotland’s First Minister, even getting a glimpse of the good lady herself, although McDermid is far too discreet to reveal if she approves or disapproves of Ms Sturgeon.

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.

Let’s look at a few relatively simple background facts, and I apologise to fans of the author for whom this may be tedious. Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 – 1957) was a notable English writer, poet, classical scholar and dramatist. She introduced the aristocratic private detective Lord Peter Wimsey in her 1923 novel, Whose Body? and by the time The Nine Tailors was published in 1934, Wimsey and his imperturbable manservant Bunter were well established.