It may have been difficult for people of my parents’ generation who lived – and fought – through the grim years of WWII to distinguish one German from another. It is entirely understandable that the differences between card-carrying members of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei and the ordinary soldiers, sailors and airmen who carried out their wishes might be rather academic, especially if your street had just blown up around your ears, or you were sitting at a table clutching a telegram informing you that your husband, brother or son had been shot dead or drowned in battle.

The first author to write fiction from the viewpoint of the German military was the controversial Danish author known as Sven Hassel. His first novel Legion of The Damned (1953) was the first in a series describing the war through the eyes of men in the 27th (Penal) Panzer Regiment. The books were immensely successful, particularly in the UK, in spite of the fact that Hassel – real name Børge Willy Redsted Pedersen – was widely regarded as a traitor in his native land, because of his war service with the Wehrmacht.

More recently, Philip Kerr has written a series of very cleverly researched and convincing novels centred around a German policeman – Bernie Gunther – who manages to keep his self-respect more or less intact, despite working alongside such monsters as Reinhard Heydrich, Josef Goebbels and Arthur Nebe. The series has Gunther involved with all manner of military and political events, from the rise of Hitler in the 1930s right through to the days of the Peron rule in 1950s Argentina.

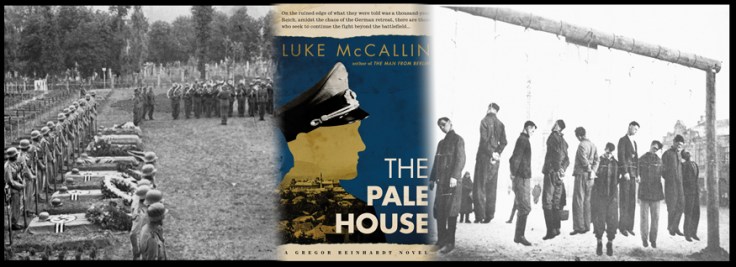

Gregor Reinhardt, like Gunther, is a former officer with the Berlin Kriminalpolizei, but lacks Gunther’s ability to duck and dive, bob and weave. He is forced out by the Nazis, but  finds employment as an officer in the Feldjaegerkorps. His creator, Luke McCallin, (right) introduced us to Hauptmann Reinhardt in The Man From Berlin (2014). In The Pale House (2015) Reinhardt is still at the extreme edge of what was, by 1945, the crumbling empire of The Third Reich. He is in Sarajevo, where the situation is, to put it mildly, anarchic. On one side hand are the Croation nationalists, the Ustase. They are, in theory, the allies of Germany, but only insofar as they have a common enemy, the communist Partisans, who are slowly gaining the upper hand.

finds employment as an officer in the Feldjaegerkorps. His creator, Luke McCallin, (right) introduced us to Hauptmann Reinhardt in The Man From Berlin (2014). In The Pale House (2015) Reinhardt is still at the extreme edge of what was, by 1945, the crumbling empire of The Third Reich. He is in Sarajevo, where the situation is, to put it mildly, anarchic. On one side hand are the Croation nationalists, the Ustase. They are, in theory, the allies of Germany, but only insofar as they have a common enemy, the communist Partisans, who are slowly gaining the upper hand.

This unholy Balkan Trinity is completed by a thoroughly disillusioned and war-weary German army who are aware, despite the failed von Stauffenberg plot to assassinate Hitler, that there is a savage and brutal race taking place between the Allied forces and the Red Army – the finishing line being Berlin itself. As the German military try to make their inevitable retreat from Sarajevo as orderly as possible, Reinhardt still has his job to do. In particular, he must find who is behind a series of mass killings, where the corpses are found with their faces disfigured. His investigations lead him to the Ustase headquarters on the banks of the Miljacka river.

The headquarters, known as The Pale House, is where the Ustase administer the beatings, torture and eventual murder of those they deem to be a threat. Even more disturbing to Reinhardt than the brutality of his notional allies is the fact that their excesses seem to be linked to his own countrymen – in particular, officers within the Feldgendarmerie, a more rank-and-file military police force than his own.

The Pale House is a gripping and brutal account of a war zone which tended to be overshadowed by the even more dramatic events further to the West. Reinhardt is, emphatically, a good man, and Luke McCallin’s skill is that he presents to us someone who loves his country, despite what it has become. We get a hint, in the final paragraphs, that Reinhardt will survive the political and military firestorm which is about to engulf him and his comrades, and that he will return – in another place, and with other crimes to solve.

You can find out more about the Luke McCallin and Hauptmann Reinhardt at the author’s website.