S5 Uncovered by James Durose-Rayner

Top of the pile is the monumental S5 Uncovered. Running to 899 pages, it is a detailed account of a police undercover operation which, if the book is too be believed, should have become a national scandal. The author is a journalist, and he tells the tale of the last days of Britain’s Serious Organised Crime Agency, SOCA, before being reborn as the National Crime Agency in 2013. At the heart of a long and complex tale is a huge money-making exercise to boost the finances of The Police Federation, the coppers’ trade union which represents officers from Constables up to the rank of Detective Chief Inspector. The Proceeds of Crime Act (2002) was intended to confiscate money and goods retained by criminals who had been convicted and jailed. In this instance huge amounts of cash and goods were taken from Sheffield gangsters, and transferred to the coffers of TPF. The author says that a BBC Panorama film about the scam was made, but never broadcast. S5 Uncovered is available now.

A Deadly Thaw by Sarah Ward

Sarah Ward introduced us to Derbyshire policeman Inspector Francis Sadler in her 2015 novel, In Bitter Chill. Now, she continues the weather metaphor with a murder mystery where not only the perpetrator is unknown but so, it transpires, is the victim. This a police procedural set in Ward’s home county of Derbyshire, and it concerns the 2004 murder of a man called Andrew Fisher. His wife, Lena, is convicted of his killing, and serves 12 years behind bars. You only die once, they say, but in 2016, with Lena Fisher once again free, the corpse of a man identified as Andrew Fisher is found in a disused mortuary. Sadler and his team face their biggest challenge to discover the truth behind the curtain of lies ad deception. A Deadly Thaw is available as a Kindle and in print versions.

Black Night Falling by Rod Reynolds

Charlie Yates is a bitter and disillusioned journalist in post WW2 America. Are there any sweetly optimistic ones, I wonder? If there are, they are not in Charlie’s friendship circle. In the book prior to this one, The Dark Inside, Charlie was involved in a noir-ish tale of death and corruption on the border between Texas and Arkansas. Having sought temporary solace in the more laid-back surroundings of California, he is now back in the land of moonshine, chewing baccy and denim cover-alls, when an old friend is desperate for his help. You might be surprised to learn that, for a writer who can so vividly recreate the menace and skin prickle of a hot Southern night, Rod Reynolds is a confirmed Londoner. Black Night Falling will be out in August on Kindle, and in the spring of 2017 in print.

Homo Superiors by L.A. Fields

Fields takes one of the most infamous murder cases of the 20th century, and reshapes it with a modern ambience. In 1924 Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two bored and wealthy Chicago students kidnapped and killed a 14 year-old boy, Robert Franks. The killers, dazzled by their own perceived intellectual superiority, and their admiration for the writings of Nietzsche, were convinced that they they had committed the perfect crime. Of course, they hadn’t, but they escaped the death penalty after a trial where they were defended by the celebrated lawyer, Clarence Darrow. In Fields’ version, we are still in Chicago, but she explores the brittle intellectual pretensions of Ray and Noah, as they make the same errors as their real-life counterparts. Homo Superiors is available as a Kindle or a paperback from Amazon.

Investigating Mr Wakefield by Rob Gittins

The Welsh publishers Y Lolfa have carved a niche for themselves as publishers of all kinds of books in the Welsh language, but they also an impressive list of Welsh authors who write in English. One such is Rob Gittins, a TV screenwriter by trade. His debut novel, Gimme Shelter, was a brutal and no-holds-barred account of a Witness Protection officer who locks horns with a fiendish serial killer. In his latest book, he moves away from the world of police investigations, and into the thorny world of personal relationships, and what happens when one obsessive man begins to suspect that his partner is deceiving him. As a former war photographer, Jack Connolly is on intimate terms with the details of death, but when he turns his meticulous sharp focus on someone to whose life he has intimate access, the results are terrifying. You can get Investigating Mr Wakefield from the publisher, or from Amazon.

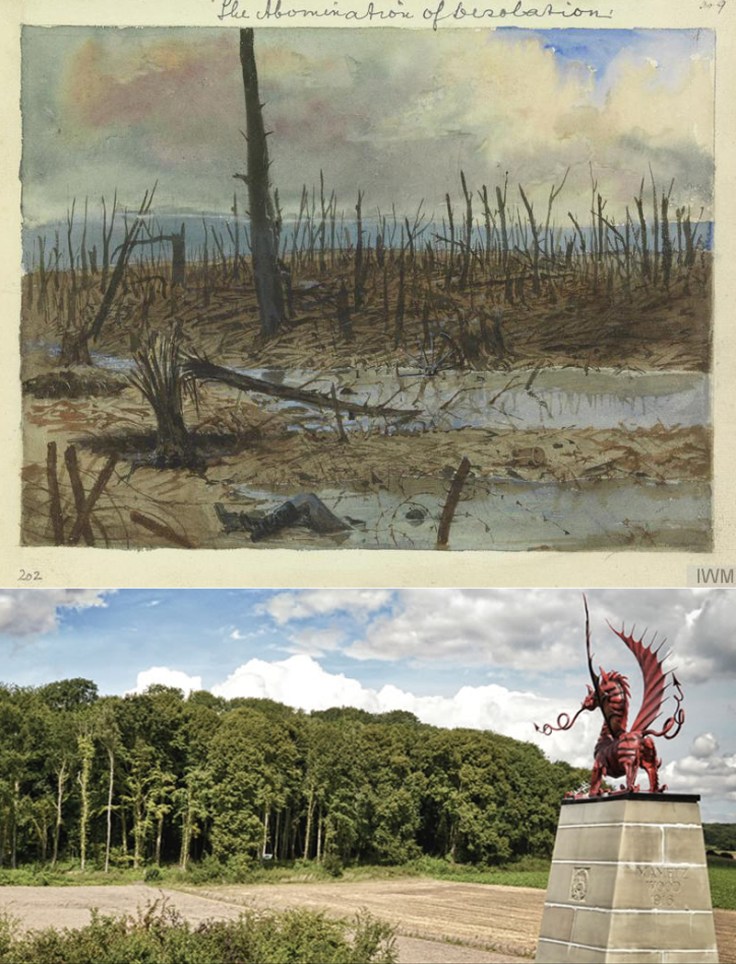

As a delightful bonus, the people at Y Lolfa also sent me the latest book by Dr Jonathan Hicks. I had reviewed – and enjoyed – two previous books by the academic and historian, The Dead of Mametz and Demons Walk Among Us. Both featured investigations by a Military Policeman, Thomas Oscendale. Now, on the centenary of the Battle of The Somme, Hicks has produced an account of a military action which has come to be synonymous with the memory of Welsh soldiers who took part. The Welsh at Mametz Wood, Somme 1916 is the story of the 20,000 men of the 38th Welsh Division. They were all volunteers, poorly trained and inadequately led for the massive task of evicting experienced German troops from the heavily fortified wood. They eventually succeeded, at a terrible cost, and Hicks seeks to put the record straight about an event over which, at the time, the 38th Division received much criticism. Below – Mametz Wood, then and now.

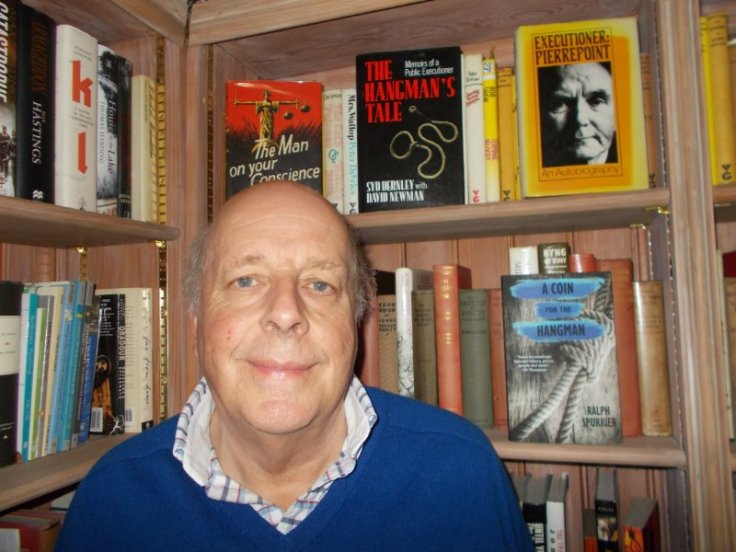

A REAL LIFE SUSSEX BOOK DEALER called Ralph Spurrier has written a book. It starts in the present day, with a Sussex book dealer, name of – you guessed it – Ralph Spurrier, and Mr S has bought a job lot of books and bits. Their erstwhile owner is dead, and his bungalow and its contents are being sold at auction. The fictional Mr S – and probably his real-life doppelganger – make their livings by buying van-loads of books in the hope that somewhere in the pile of book club reprints and assorted dross there will be a first edition, something autographed, or another rarity which can be sold on to pay the bills.

A REAL LIFE SUSSEX BOOK DEALER called Ralph Spurrier has written a book. It starts in the present day, with a Sussex book dealer, name of – you guessed it – Ralph Spurrier, and Mr S has bought a job lot of books and bits. Their erstwhile owner is dead, and his bungalow and its contents are being sold at auction. The fictional Mr S – and probably his real-life doppelganger – make their livings by buying van-loads of books in the hope that somewhere in the pile of book club reprints and assorted dross there will be a first edition, something autographed, or another rarity which can be sold on to pay the bills.

A LILY OF THE FIELD by John Lawton

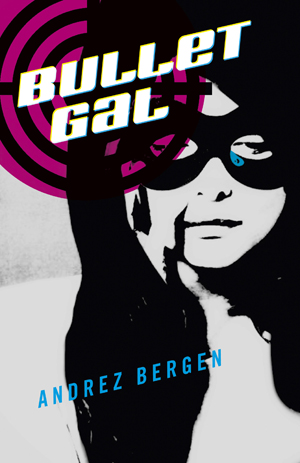

A LILY OF THE FIELD by John Lawton What noir enables me to do is isolate those genres and render them a little different, whether it be an homage to golden age comic books from the 1940s (Bullet Gal), or rebooting a medieval romance (Black Sails, Disco Inferno). The standards of noir – a certain sense of cynicism, the not-so-happy outcome, mood, drinks, and cutting dialogue – bring out the best in any such side-step.

What noir enables me to do is isolate those genres and render them a little different, whether it be an homage to golden age comic books from the 1940s (Bullet Gal), or rebooting a medieval romance (Black Sails, Disco Inferno). The standards of noir – a certain sense of cynicism, the not-so-happy outcome, mood, drinks, and cutting dialogue – bring out the best in any such side-step.

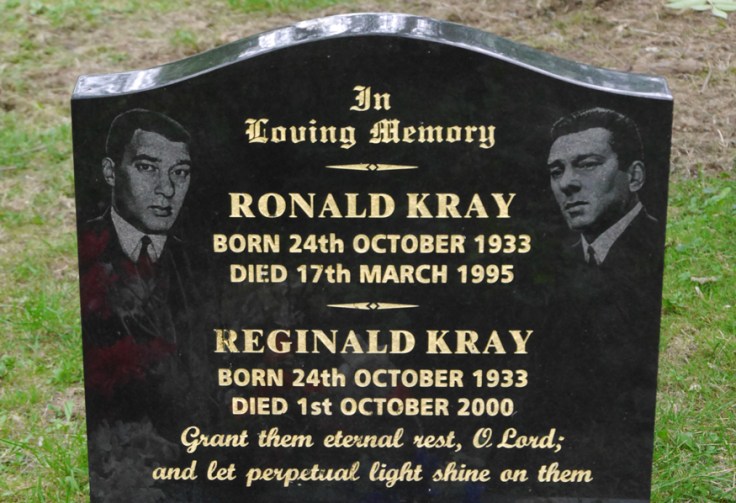

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

REGGIE AND RONNIE KRAY have been the subject of almost as many books, documentaries and dramas as their 19th century near-neighbour Jack the Ripper. The East End that he – whoever he was – knew has changed almost beyond recognition. The Bethnal Green of the Krays is heading in the same direction, but a few landmarks remain unscathed. They were born out in Hoxton in October 1933, Reggie being the older by ten minutes. The family moved into Bethnal Green in 1938, and they lived at 178 Vallance Road. That house no longer stands, modern houses having been built on the site (left)

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known.

George Cornell (right) had known the twins from childhood. Their careers had developed more or less on similar lines, except that Cornell became the enforcer for the Richardsons. On 7th March 1966 there was a confused shoot-out at a club in Catford. Members of the Kray gang and the Richardsons gang were involved. At some point, George Cornell had been heard to refer to Ronnie Kray as a “fat poof.” That might seem unkind, but was not totally inaccurate. Ronnie was certainly plumper than his lean and hungry twin, and his liking for handsome boys was well known. On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

On the evening of 9th March, Cornell and an associate were unwise enough to call in for a drink at a The Blind Beggar pub on Whitechapel Road, very much in Kray territory. Some thoughtful soul telephoned Ronnie Kray, who was drinking in a nearby pub, The Lion in Tapp Street (left). Ronnie, pausing only to collect a handgun made straight for the Blind Beggar, strode in, and shot George Cornell in the head at close range. His death was almost instantaneous. Needless to say, no-one else in the pub had seen anything. Pictured below are a post mortem photograph of Cornell, and the bloodstained floor of The Blind Beggar. Below that is the fatal pub, then and now.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins.

Folklore has it that now that Ronnie had ‘done the big one’, there was pressure on Reggie to match his twin’s achievement. The chance was over a year in coming. Jack McVitie (right) was a drug addicted criminal enforcer who worked, on and off, for the Krays. His nickname ‘The Hat’ was because he was embarrassed about his thinning hair, and always wore a trademark trilby. McVitie had taken £500 from the Krays to kill someone, had botched the job, but kept the money. He had also, unwisely,been heard to bad-mouth the twins. On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.

On the night of 29th October 1967, McVitie was lured to a basement flat in Evering Road, Stoke Newington,(left) on the pretext of a party. There, he was met by Reggie Kray and other members of the firm. Kray’s attempt to shoot McVitie misfired – literally – and instead, he stabbed McVitie repeatedly with a carving knife. McVitie’s body was never found, and the stories about his eventual resting place range from his being fed to the fishes of the Sussex coast to being buried incognito in a Gravesend cemetery.

WHEN LONDON BECAME THE PRIMARY TARGET of Luftwaffe bombers in World War II, one of the first responses of the government was to institute a night-time blackout. Given that the silvery ribbon of the River Thames couldn’t be hidden, and German knowledge of the whereabouts of factories and docks, the effect of the blackout was more psychological than practical. What it did do was to liberate criminals from the fear of being seen by what remained of the police force – bear in mind that most able bodied men of fighting age were very quickly drafted into the armed forces. Despite the affectionate folk myth of plucky Londoners ‘grinning and bearing it’, domestic crime rocketed. An often used wheeze was for criminals to dress up as Air Raid Wardens. In the darkness and confusion, they could raid shops and be about their dishonest business with a new freedom. Looting was not uncommon, and more than one gang discovered the effectiveness of going around the dark streets in a fake ambulance.

WHEN LONDON BECAME THE PRIMARY TARGET of Luftwaffe bombers in World War II, one of the first responses of the government was to institute a night-time blackout. Given that the silvery ribbon of the River Thames couldn’t be hidden, and German knowledge of the whereabouts of factories and docks, the effect of the blackout was more psychological than practical. What it did do was to liberate criminals from the fear of being seen by what remained of the police force – bear in mind that most able bodied men of fighting age were very quickly drafted into the armed forces. Despite the affectionate folk myth of plucky Londoners ‘grinning and bearing it’, domestic crime rocketed. An often used wheeze was for criminals to dress up as Air Raid Wardens. In the darkness and confusion, they could raid shops and be about their dishonest business with a new freedom. Looting was not uncommon, and more than one gang discovered the effectiveness of going around the dark streets in a fake ambulance.

Rather like the Whitechapel killer of 1888, the attacks became more frenzied and the mutilations more awful. Weapons used included razor blades, a can opener, a kitchen knife and a candlestick. After the frenzied killings of Margaret Lowe and Doris Jouannet, Sir Bernard Spilsbury (right), the most celebrated medical examiner of the century, remarked that the murders were the work of “a savage sexual maniac”. The press were quick to coin a new name for the killer, and for the brief period of his notoriety, he became known as ‘The Blackout Ripper’.

Rather like the Whitechapel killer of 1888, the attacks became more frenzied and the mutilations more awful. Weapons used included razor blades, a can opener, a kitchen knife and a candlestick. After the frenzied killings of Margaret Lowe and Doris Jouannet, Sir Bernard Spilsbury (right), the most celebrated medical examiner of the century, remarked that the murders were the work of “a savage sexual maniac”. The press were quick to coin a new name for the killer, and for the brief period of his notoriety, he became known as ‘The Blackout Ripper’. Cummins was tried at the Old Bailey in April 1942, and was very quickly found guilty. The judge was none other than Lord Chief Justice Humphreys, who had been involved in many of the most high profile trials of the century. On the day Cummins was hanged on the morning of 25th June, 1942, and the hangman was Albert Pierrepoint. It is said that an daytime air-raid raged overhead when Cummins died, a bitter irony given the circumstances of his crimes.

Cummins was tried at the Old Bailey in April 1942, and was very quickly found guilty. The judge was none other than Lord Chief Justice Humphreys, who had been involved in many of the most high profile trials of the century. On the day Cummins was hanged on the morning of 25th June, 1942, and the hangman was Albert Pierrepoint. It is said that an daytime air-raid raged overhead when Cummins died, a bitter irony given the circumstances of his crimes.

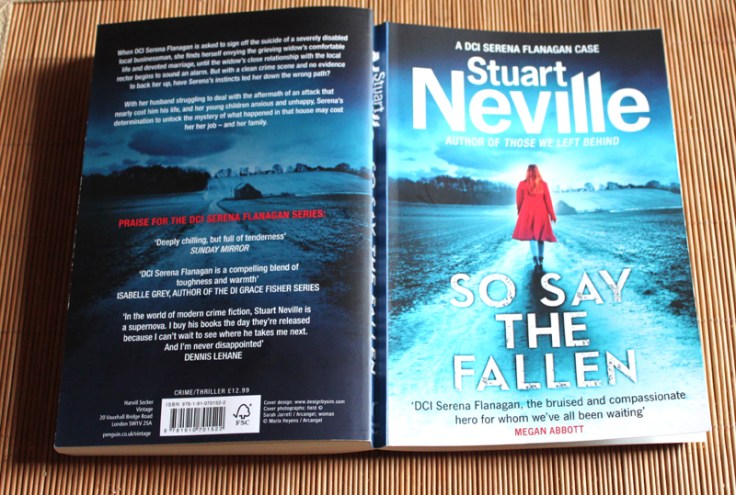

Stuart Neville (left) returns with another hard-bitten and edgy tale of life and crimes in Northern Ireland. Set in a fictional village on the edge of Belfast, we are reunited with DCI Serena Flanagan, who first appeared in Those We Left Behind. Like much of life in Ulster, fictional and real, religion and the stresses and strains it places on secular life is never far from the surface. The sacred influence in this case is provided by the Reverend Peter McKay. The clergyman is a widower, but we find that he has been taking his parochial duties above and beyond what is normally expected. The recipient of his pastoral care is Roberta, the attractive wife of Henry Garrick.

Stuart Neville (left) returns with another hard-bitten and edgy tale of life and crimes in Northern Ireland. Set in a fictional village on the edge of Belfast, we are reunited with DCI Serena Flanagan, who first appeared in Those We Left Behind. Like much of life in Ulster, fictional and real, religion and the stresses and strains it places on secular life is never far from the surface. The sacred influence in this case is provided by the Reverend Peter McKay. The clergyman is a widower, but we find that he has been taking his parochial duties above and beyond what is normally expected. The recipient of his pastoral care is Roberta, the attractive wife of Henry Garrick. As they say, in America, “School’s Out!” On the evening of Saturday 28th June 2008, school was pretty much out for a group of teenage London boys. Their GCSE exams were finally over and, despite nor being legally old enough to drink, they were having a night out to celebrate. They went to Shillibeers (left), a popular bar and brasserie in Holloway. Among the group was Ben Kinsella, a 16 year-old pupil at Holloway School.

As they say, in America, “School’s Out!” On the evening of Saturday 28th June 2008, school was pretty much out for a group of teenage London boys. Their GCSE exams were finally over and, despite nor being legally old enough to drink, they were having a night out to celebrate. They went to Shillibeers (left), a popular bar and brasserie in Holloway. Among the group was Ben Kinsella, a 16 year-old pupil at Holloway School.