The central characters of this powerful novel are Grand Duchess Militza Nikoleyevna, married to a cousin of Tsar Nicholas II, and her daughter Princess Nadezhda Petrovna. The background, as you might guess, is the decline and fall of the Romanovs, and two headed monster that was WW1 and the Russian Revolution.

The early pages set the tone. The catastrophic failures of the Russian Army, culminating with the Battle of Tannenberg, turn the world on its head for Russian citizens, be they of noble birth or peasant stock. Of course, at that time, the centre of the Imperial Universe was Petrograd, and we learn of the impact on those close to the Tsar’s court of the murder of Rasputin. Historians both professional and, like myself, amateur, have long pondered the great paradox that is Russia. Perhaps no other place on earth can provide such examples of great beauty in architecture and music, but also of the most bestial behaviour by human beings. One of the great ironies is that the place where the revolution burst into flames was a city literally built on a swamp, and costing the lives of 100,000 workers. They died to give Peter the Great access to The Baltic and – arguably – a pathway to make Russia a great international nation.

The Witch of the title is Militza. In her private thoughts she describes how she ‘created’ Rasputin. What are we to make of this? She muses:

“Maybe if she explained how she and her sister fashioned the Holy Satyr from wax, mixed it with dust from a poor man’s grave and the icon of Saint John the Baptist; how she moulded the creature, rolling and warming the wax in her hands; how she baptised it with the soul of an unborn child, the dried up foetus, miscarried by the grand Duchess Vladimir all those years ago; and how they’d called on the Four Winds and the koldun -the insatiable, unconscionable, licentious, duplicitous, covetous, impious, soused, drunk and self appointed Holy Man man from Siberia – Rasputin had come. Just as she had commanded.”

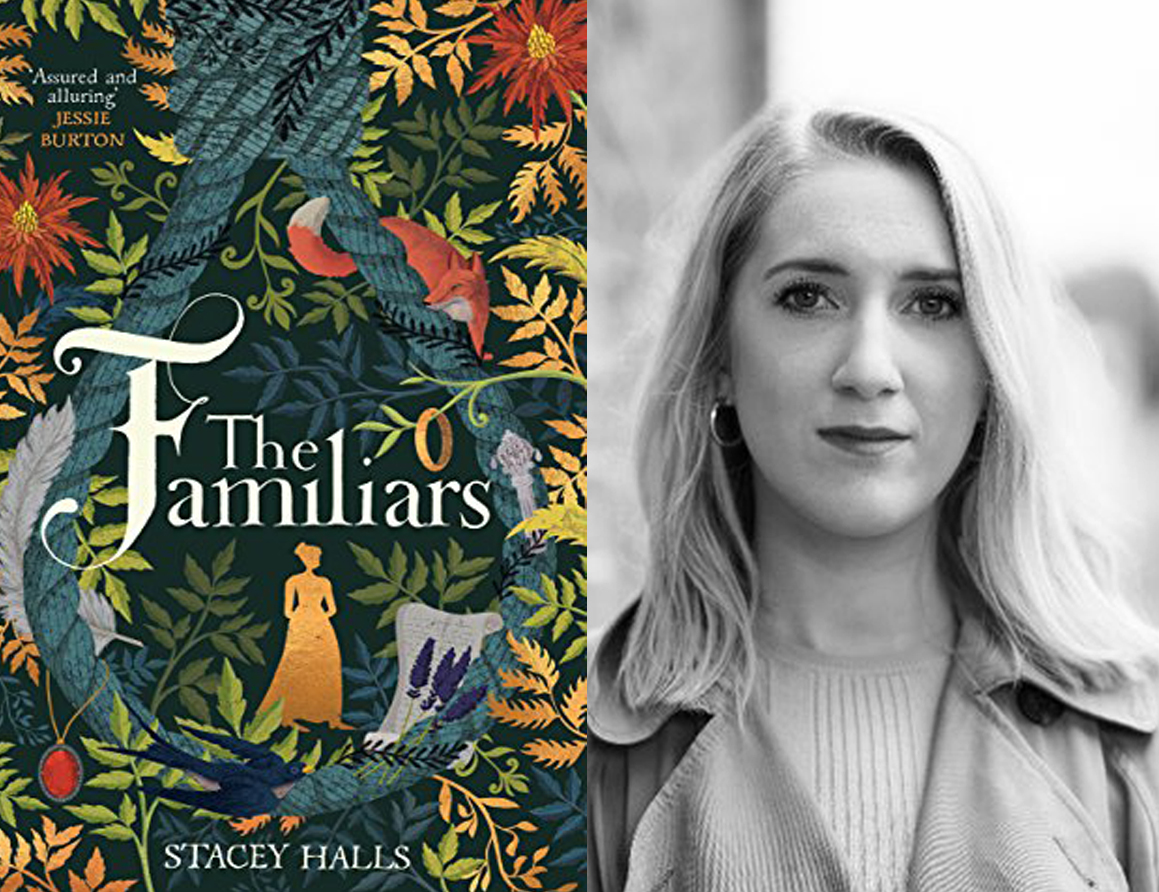

Nadezhda is also a paradox. Despite her scorn for her mother’s ‘sorcery’ she carries with her a bottle of water, allegedly from the frozen waters of the River Neva that melted around the corpse of Rasputin after he was hauled from its depths. While nursing an admirer, a young man called Nicholas Orlof, severely injured in the unrest, she falls back on the old wisdom of her mother. The author (left) allows us to make up our own minds as to the efficacy of the spells and incantations.

Nadezhda is also a paradox. Despite her scorn for her mother’s ‘sorcery’ she carries with her a bottle of water, allegedly from the frozen waters of the River Neva that melted around the corpse of Rasputin after he was hauled from its depths. While nursing an admirer, a young man called Nicholas Orlof, severely injured in the unrest, she falls back on the old wisdom of her mother. The author (left) allows us to make up our own minds as to the efficacy of the spells and incantations.

The novel doesn’t take sides politically, but I must confess I have a long standing sympathy for the Russian nobility, and it still angers me to read about the utter brutality of what happened on 16th/17th July 1918 in Yekaterinburg. Yes, Nicholas II was weak, and his regime presided over breathtaking inequality by modern standards, but his sins pale into insignificance when judged against those of Lenin, Stalin and, dare I say it, more recent rulers of Russia.

The author puts Nadezhda centre stage as revolution takes over the streets of Petrograd, and the Tsar’s soldiers commit atrocities in an attempt to emulate Canute and turn back an inexorable tide. She is drawn into the animal vigour of the protests, bread marches and the resounding choruses of The Marseillaise. Perhaps I am wrong to say this, but it reminds me of modern day youngsters from impeccable middle class backgrounds taking to the streets to demand the downfall of Israel, or attacking paintings to draw attention to climate change.

As we know, the Tsar’s abdication saved neither him nor his wife and children. Historians still argue over the apparent rejection, by King George V, of his cousin’s request for sanctuary. This book suggests that, even if it had been granted, the Tsar and family would never have made it to Britain unscathed. When Lenin returns in his sealed train, the gunpowder keg explodes:

“The Neva was thawing. There was an open stream some 20 yards wide alongside the banks while the centre still remained frozen. And along with the filth swirling through the streets and the slush came the rats and the rebels. No one was working. No one wanted to work. No one was being paid. It was anarchy. Nearly 2,000,000 had now deserted the front and they were loitering in the city with nothing to do. Starving, cold, penniless and angry, they were ripe for the plucking. All Lenin had to do was reach out and take them.”

And take them he did. Militza, Nadezhda and the remainder of the minor Romanovs escape to Crimea where they just about manage to survive until they are rescued by ships of the British navy. A few minutes on Google will reassure readers that Malitza, Nadezhda and Nicholas lived long lives, but each – of course – died thousands of miles away from Petrograd. Only the most rabid and bitter socialist would fail to be touched by the sheer horror of the destruction of the Russian aristocracy described here. Yes, many of them were vain, privileged, and oblivious to the social injustice endemic under Romanov rule. But they were human. Like Shylock, they were entitled to ask{

“ If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die?”

This novel is the result of astonishing historical research, but above all, it is a tale of human resilience, courage and that ineffable human quality immortalised by the words of St Paul, “But the greatest of these is love.” Published by Aria, the book is available now in all formats.

AT THE APPROPRIATELY NAMED DEAD DOLLS HOUSE in Islington, the inventive folks at publishers Bonnier Zaffre launched Stacy Halls’ novel The Familiars with not so much a flourish as a brilliant visual fanfare.

AT THE APPROPRIATELY NAMED DEAD DOLLS HOUSE in Islington, the inventive folks at publishers Bonnier Zaffre launched Stacy Halls’ novel The Familiars with not so much a flourish as a brilliant visual fanfare. witchy tinctures using a potent combination of various precious oils. I went for Frankincense with a dash of Patchouli. I managed to smear it everywhere and such was its potency that my wife was convinced that I had been somewhere less innocent than a book launch.

witchy tinctures using a potent combination of various precious oils. I went for Frankincense with a dash of Patchouli. I managed to smear it everywhere and such was its potency that my wife was convinced that I had been somewhere less innocent than a book launch.