You might guess that a crime novel featuring an amateur detective called Gawaine St Clair is not going to take you down many mean streets; furthermore, were one to Frenchify its chromatic tint, then it would probably be nearer beige than noir. This being said, if you are a Golden Age fan, like dry humour, enjoy a clue-laden whodunnit and are never happier than when luxuriating in the follies and foibles of the English middle classes, then Cherith Baldry’s Dangerous Deceits will be a joy.

You might guess that a crime novel featuring an amateur detective called Gawaine St Clair is not going to take you down many mean streets; furthermore, were one to Frenchify its chromatic tint, then it would probably be nearer beige than noir. This being said, if you are a Golden Age fan, like dry humour, enjoy a clue-laden whodunnit and are never happier than when luxuriating in the follies and foibles of the English middle classes, then Cherith Baldry’s Dangerous Deceits will be a joy.

Gawaine St Clair seems to be a man of independent means, not unlike his aristocratic predecessor Lord Peter Death Bredon Wimsey, and his affluence enables him to take up criminal investigations without having to make excuses to an employer for his absence from the workplace. In this case he is called upon by his aunt Christobel to solve the mysterious death of a vicar. Father Tom Coates disappeared into his vestry moments before the beginning of a service, and was not seen again until he was found some time later, all life extinct due to a fatal blow to his head with the time-honoured blunt object.

It needs to be said at this point that the novel is very, very ‘churchy’. I use the term to describe a way of life centred around the Anglican church, with attendant church wardens, vergers, flower ladies, Parochial Church Councils, the occasional Bishop, and heated disputes over liturgical practices. Anthony Trollope de nos jours? Possibly, but as an Anglican, albeit rather lapsed, I share Cherith Baldry’s obvious love of the sonorous prose of The Book of Common Prayer – the proper 1662 version, not some squeaky clean modern adaptation designed to appeal to ‘the younger generation’. She uses suitably resonant quotes as her chapter headings, none more appropriately than:

“Man that is born of a woman hath but a short time to live.”

St Clair is faced with a whole repertory company of likely suspects, all – or none – of whom may have had their reasons to bash Father Tom’s head in. In no particular order, we have a choleric prep school Headmaster straight out of Decline and Fall, a woman denied communion because of her marital woes, a glib local solicitor, the dead man’s brother and sister, with whom he owned valuable shares in a family business, and a dowdy local GP with a beautiful and sophisticated wife.

Gawaine may be too arch and precious for some tastes but he fits perfectly into the Home Counties landscape with its manicured village greens and faux Tudor dwellings. I thoroughly enjoyed Dangerous Deceits and Father Tom’s killer is unmasked not amid the dusty shelves of a country house library, but in the altogether more fractious atmosphere of an extraordinary (in the procedural sense) meeting of the Ellingwood PCC. The solution, as in many a whodunnit, rests with everyone – including Gawaine, the local coppers and, in this particular case, me – making a seemingly obvious assumption early in the piece.

Gawaine may be too arch and precious for some tastes but he fits perfectly into the Home Counties landscape with its manicured village greens and faux Tudor dwellings. I thoroughly enjoyed Dangerous Deceits and Father Tom’s killer is unmasked not amid the dusty shelves of a country house library, but in the altogether more fractious atmosphere of an extraordinary (in the procedural sense) meeting of the Ellingwood PCC. The solution, as in many a whodunnit, rests with everyone – including Gawaine, the local coppers and, in this particular case, me – making a seemingly obvious assumption early in the piece.

Cherith Baldry (right) is an acclaimed writer of children’s fiction and fantasy novels. The first in her Gawaine St Clair series was Brutal Terminations, which came out in February 2018. Dangerous Deceits is available now and is published by Matador.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the first book in this series, The Word Is Murder (and you can read my review

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the first book in this series, The Word Is Murder (and you can read my review  The abundance of questions will give away the fact that this is a tremendous whodunnit. Horowitz (right) tugs his forelock in the direction of the great masters of the genre and, while we don’t quite have the denouement in the library, we have a bewildering trail of red herrings before the dazzling final exposition. But there is more. Much, much more. Horowitz’s portrayal of himself is beautifully done. I have only once brushed shoulders with the gentleman at a publisher’s bash, so I don’t know if the self-effacing tone is accurate, but it is warm and convincing. More than once he finds himself the earnest but dull Watson to Hawthorne’s ridiculously clever Holmes.

The abundance of questions will give away the fact that this is a tremendous whodunnit. Horowitz (right) tugs his forelock in the direction of the great masters of the genre and, while we don’t quite have the denouement in the library, we have a bewildering trail of red herrings before the dazzling final exposition. But there is more. Much, much more. Horowitz’s portrayal of himself is beautifully done. I have only once brushed shoulders with the gentleman at a publisher’s bash, so I don’t know if the self-effacing tone is accurate, but it is warm and convincing. More than once he finds himself the earnest but dull Watson to Hawthorne’s ridiculously clever Holmes.

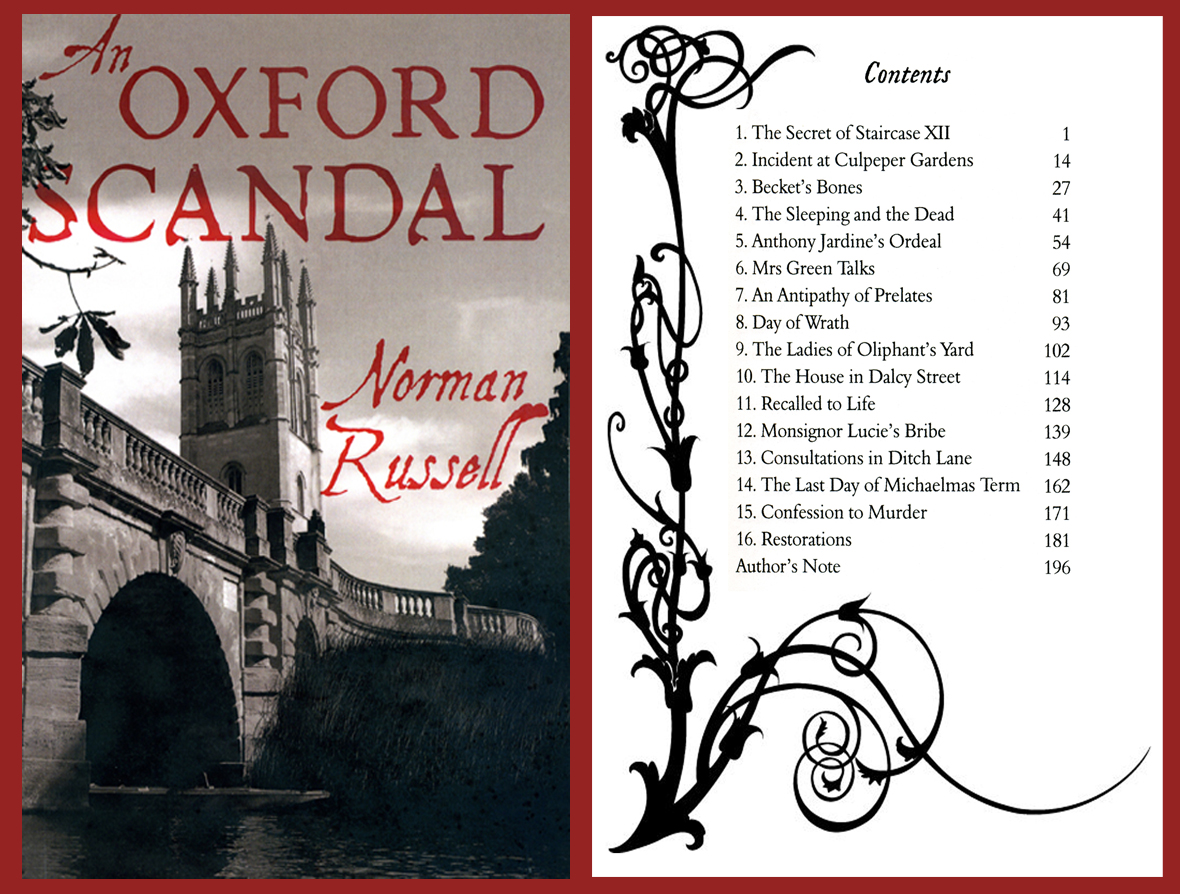

Oxford, 1895. The spires may well be dreaming, but for Anthony Jardine, Fellow of St Gabriel’s College, the nightmare is just beginning. His drug addicted wife is found stabbed to death, slumped in the corner of a horse tram carriage. His mourning is shattered when his mistress is also found dead – murdered in the house she shares with her elderly eccentric husband. With a background story of an archaeological discovery threatening to shake the English religious establishment to its very roots, Inspector James Antrobus must avoid the temptation to make Jardine a swift and easy culprit. Helped by the uncanny perception of Sophia Jex-Blake, a pioneering woman doctor, Antrobus finds the answer to the killings lies in London, just forty miles away on the railway.

Oxford, 1895. The spires may well be dreaming, but for Anthony Jardine, Fellow of St Gabriel’s College, the nightmare is just beginning. His drug addicted wife is found stabbed to death, slumped in the corner of a horse tram carriage. His mourning is shattered when his mistress is also found dead – murdered in the house she shares with her elderly eccentric husband. With a background story of an archaeological discovery threatening to shake the English religious establishment to its very roots, Inspector James Antrobus must avoid the temptation to make Jardine a swift and easy culprit. Helped by the uncanny perception of Sophia Jex-Blake, a pioneering woman doctor, Antrobus finds the answer to the killings lies in London, just forty miles away on the railway. Norman Russell (right) is a writer and academic, who has had fifteen novels published. He is an acknowledged authority on Victorian finance and its reflections in the literature of the period, and his book on the subject, The Novelist and Mammon, was published by Oxford University Press in 1986. He is a graduate of Oxford and London Universities. After military service in the West Indies, he became a teacher of English in a large Liverpool comprehensive school, where he stayed for twenty-six years, retiring early to take up writing as a second career.

Norman Russell (right) is a writer and academic, who has had fifteen novels published. He is an acknowledged authority on Victorian finance and its reflections in the literature of the period, and his book on the subject, The Novelist and Mammon, was published by Oxford University Press in 1986. He is a graduate of Oxford and London Universities. After military service in the West Indies, he became a teacher of English in a large Liverpool comprehensive school, where he stayed for twenty-six years, retiring early to take up writing as a second career.

Many people in their sixties – particularly those who are comfortably off – plan ahead for their own funerals. Daytime television programmes are interspersed with advertisements featuring either be-cardiganed senior citizens smugly telling us that they have taken insurance with Coffins ‘R’ Us, or rueful widows plaintively wishing that they had been better prepared for the demise of poor Jack, Barry or Derek. However, it would be unusual to hear that the be-cardiganed senior citizen had died only hours after planning and paying for their own send-off from the world of the living.

Many people in their sixties – particularly those who are comfortably off – plan ahead for their own funerals. Daytime television programmes are interspersed with advertisements featuring either be-cardiganed senior citizens smugly telling us that they have taken insurance with Coffins ‘R’ Us, or rueful widows plaintively wishing that they had been better prepared for the demise of poor Jack, Barry or Derek. However, it would be unusual to hear that the be-cardiganed senior citizen had died only hours after planning and paying for their own send-off from the world of the living. During the story, Horowitz (right) drops plenty of names but, to be fair, the real AH has plenty of names to drop. His CV as a writer is, to say the least, impressive. But just when you might be thinking that he is banging his own drum or blowing his own trumpet – select your favourite musical metaphor – he plays a tremendous practical joke on himself. He is summoned to Soho for a vital pre-production meeting with Steven and Peter (that will be Mr Spielberg and Mr Jackson to you and me), but his star gazing is rudely interrupted by none other than the totally unembarrassable person of Daniel Hawthorne, who barges his way into the meeting to collect Horowitz so that the pair can attend the funeral of Diana Cowper.

During the story, Horowitz (right) drops plenty of names but, to be fair, the real AH has plenty of names to drop. His CV as a writer is, to say the least, impressive. But just when you might be thinking that he is banging his own drum or blowing his own trumpet – select your favourite musical metaphor – he plays a tremendous practical joke on himself. He is summoned to Soho for a vital pre-production meeting with Steven and Peter (that will be Mr Spielberg and Mr Jackson to you and me), but his star gazing is rudely interrupted by none other than the totally unembarrassable person of Daniel Hawthorne, who barges his way into the meeting to collect Horowitz so that the pair can attend the funeral of Diana Cowper.