By my reckoning this is the fifteenth outing for Alex Gray’s veteran Glaswegian copper, William – now Detective Superintendent – Lorimer. A woman – who, if witnesses are to be believed, was a deeply unpleasant person – is found stabbed to death, her hands clutched around a top-of-the-range kitchen knife. Dorothy Guilford was widely disliked both within her own family and further afield while her husband, Peter – by contrast – has few detractors. Yet the working hypothesis of the police investigating Dorothy’s demise is that Peter Guilford did the deed.

Lorimer has become bogged down in a partially – and only partially – successful investigation into murder, prostitution and people trafficking based in Aberdeen. In the Granite City some entrepreneurs, denied a living by the decline in the oil and gas industries, have taken to trading in other commodities – human lives. However, to borrow the memorable line from The Scottish Play, Lorimer’s team have “scotch’d the snake, not kill’d it.” The head of the gang responsible for taking young and innocent Romany women from impoverished Slovakian villages, and setting them to work in Scottish brothels is known only as “Max”. The very mention of his name is enough to silence witnesses, even those who have every reason to long for his downfall. But how – if at all – is Max connected to Peter Guilford, arrested for his wife’s murder, but now beaten within an inch of his life while on remand in Glasgow’s Barlinnie prison?

Lorimer has become bogged down in a partially – and only partially – successful investigation into murder, prostitution and people trafficking based in Aberdeen. In the Granite City some entrepreneurs, denied a living by the decline in the oil and gas industries, have taken to trading in other commodities – human lives. However, to borrow the memorable line from The Scottish Play, Lorimer’s team have “scotch’d the snake, not kill’d it.” The head of the gang responsible for taking young and innocent Romany women from impoverished Slovakian villages, and setting them to work in Scottish brothels is known only as “Max”. The very mention of his name is enough to silence witnesses, even those who have every reason to long for his downfall. But how – if at all – is Max connected to Peter Guilford, arrested for his wife’s murder, but now beaten within an inch of his life while on remand in Glasgow’s Barlinnie prison?

Alex Gray gives us an enthralling supporting cast. Ever present are the consultant psychologist, Dr Solomon Brightman and his wife Rosie, a pathologist who has the essential – but unenviable – task of literally eviscerating the human bodies which are the result of murder most foul. Young Detective Constable Kirsty Wilson goes above and beyond the call of duty to make sense of the confusing and contradictory ‘facts’ of the Dorothy Guilford case. All the while, though, she is facing a personal dilemma. Her boyfriend has just won the promotion of his dreams – a prominent position in his bank’s Chicago operation. But will Kirsty cast aside her own imminent promotion to Detective Sergeant, and follow James in his pursuit of The American Dream?

The British police procedural – the Scottish police procedural, even – is a crowded field, and each author and their characters tries to bring something different to choosy readers. Where Alex Gray (right) makes her mark, time and time again, is that she is unafraid to show the better things of life, the timeless touches of nature in a summer garden, or the warmth of affection between characters, particularly, of course, the bond between William and Margaret Lorimer. Here is one such moment:

The British police procedural – the Scottish police procedural, even – is a crowded field, and each author and their characters tries to bring something different to choosy readers. Where Alex Gray (right) makes her mark, time and time again, is that she is unafraid to show the better things of life, the timeless touches of nature in a summer garden, or the warmth of affection between characters, particularly, of course, the bond between William and Margaret Lorimer. Here is one such moment:

“She smiled as he selected a bottle from the fridge. The dusk was settling over the treetops, a haze of apricot light melting into the burnished skies …….she pulled a cardigan across her shoulders as she settled down on the garden bench, eyes gazing upwards as a thrush trilled its liquid notes. Live in the moment, she thought, breathing in the sweetness that wafted from the night-scented stocks.”

This is not to say that Gray wears rose-tinted spectacles. This is far, far from the case, and her scenes depicting the violence – both emotional and physical – that we inflict on one another are powerful, visceral and compelling.

A particular mention needs to be made of the deft touches Gray uses when writing about Margaret Lorimer. Here is a woman much to be envied in many ways. She has a loving husband, a stable and prosperous home life, and a teaching career in which she touches the lives of so many young people in her school. And yet, and yet. A cloud hovers over Margaret, and it is one that can never be blown from the otherwise blue sky. The couple’s inability to have children sometimes weighs heavily, especially when friends and colleagues are gifted with children. But Gray never allows Margaret to become embittered, and if she envies Rosie and Solomon, for example, then she keeps it to herself.

Only The Dead Can Tell is, quite simply, superbly written and plotted. It sums up everything that is golden and enthralling about a good book. It is published by Sphere, and will be out as a hardback and a Kindle on 22nd March.

By 22nd March 2018, there should be catkins on the willow and hazel, daffodils should be getting into their stride and, even if it’s a little early to be looking for summer migrants like swallows and warblers, nothing will be more welcome to lovers of good crime fiction than the return of William Lorimer in another – the fifteenth, unbelievably – police procedural set in Scotland. Since Alex Gray (left) saw Never Somewhere Else published in 2002, she has made Lorimer and his world one of the go-to destinations for anyone who loves a well-crafted crime novel, with a sympathetically portrayed central character.

By 22nd March 2018, there should be catkins on the willow and hazel, daffodils should be getting into their stride and, even if it’s a little early to be looking for summer migrants like swallows and warblers, nothing will be more welcome to lovers of good crime fiction than the return of William Lorimer in another – the fifteenth, unbelievably – police procedural set in Scotland. Since Alex Gray (left) saw Never Somewhere Else published in 2002, she has made Lorimer and his world one of the go-to destinations for anyone who loves a well-crafted crime novel, with a sympathetically portrayed central character.

I should add, at this point, that James Oswald (left) is not your regulation writer of crime fiction novels. He has a rather demanding ‘day job’, which is running a 350 acre livestock farm in North East Fife, where he raises pedigree Highland Cattle and New Zealand Romney Sheep. His entertaining Twitter feed is, therefore, just as likely to contain details of ‘All Creatures Great and Small’ obstetrics as it is to reveal insights into the art of writing great books. But I digress. I don’t know James Oswald well enough to say whether or not he puts anything of himself into the character of Tony McLean, but the scenery and routine of McLean’s life is nothing like that of his creator.

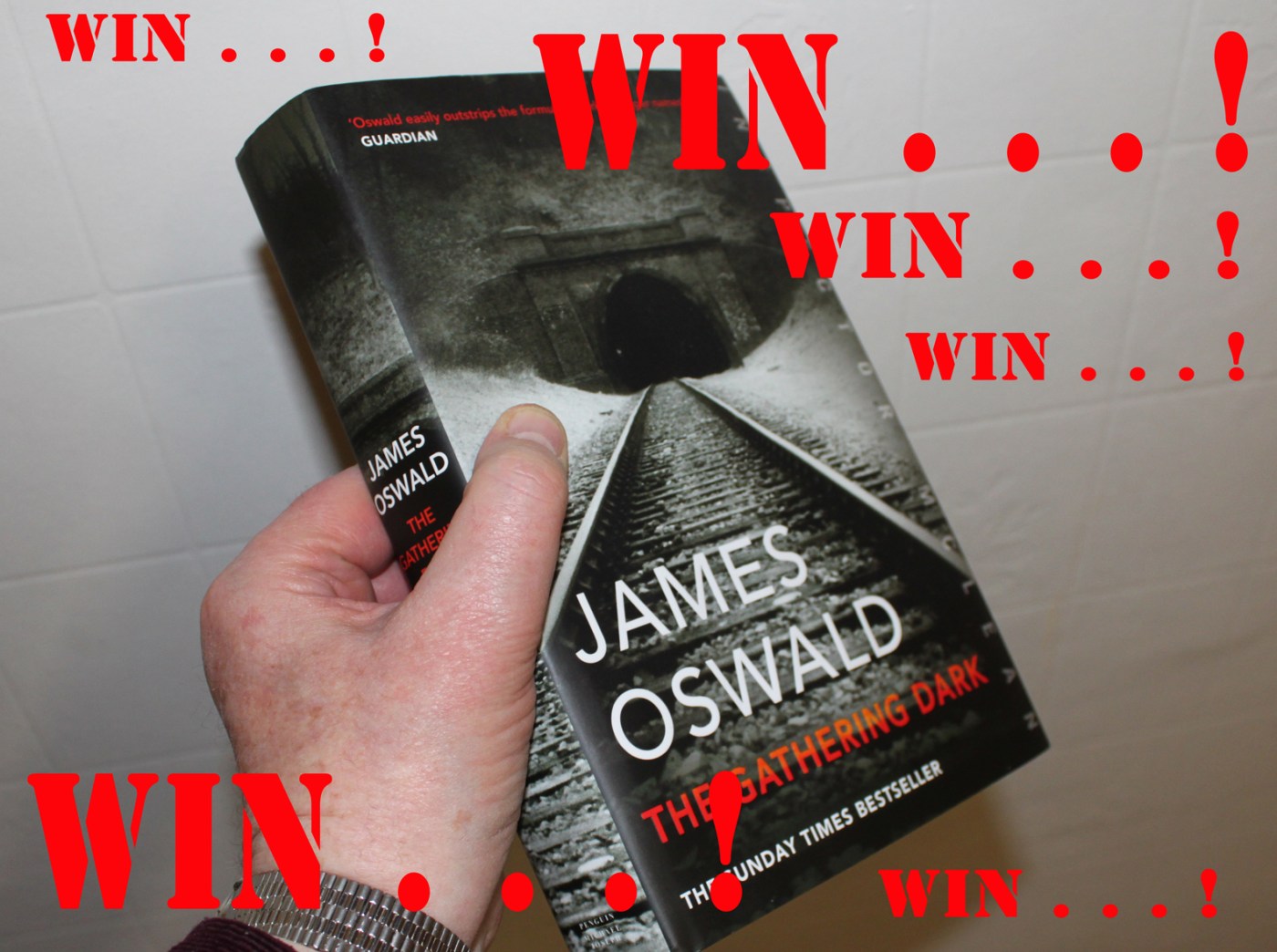

I should add, at this point, that James Oswald (left) is not your regulation writer of crime fiction novels. He has a rather demanding ‘day job’, which is running a 350 acre livestock farm in North East Fife, where he raises pedigree Highland Cattle and New Zealand Romney Sheep. His entertaining Twitter feed is, therefore, just as likely to contain details of ‘All Creatures Great and Small’ obstetrics as it is to reveal insights into the art of writing great books. But I digress. I don’t know James Oswald well enough to say whether or not he puts anything of himself into the character of Tony McLean, but the scenery and routine of McLean’s life is nothing like that of his creator. McLean is going about his daily business when he is witness to a tragedy. A tanker carrying slurry is diverted through central Edinburgh by traffic congestion on the bypass. The driver has a heart attack, and the lorry becomes a weapon of mass destruction as it ploughs into a crowded bus stop. McLean is the first police officer on the scene, and he is immediately aware that whatever the lorry was carrying, it certainly wasn’t harmless – albeit malodorous – sewage waste. People whose bodies have not been shattered by thirty tonnes of hurtling steel are overcome and burned by a terrible toxic sludge which floods from the shattered vehicle.

McLean is going about his daily business when he is witness to a tragedy. A tanker carrying slurry is diverted through central Edinburgh by traffic congestion on the bypass. The driver has a heart attack, and the lorry becomes a weapon of mass destruction as it ploughs into a crowded bus stop. McLean is the first police officer on the scene, and he is immediately aware that whatever the lorry was carrying, it certainly wasn’t harmless – albeit malodorous – sewage waste. People whose bodies have not been shattered by thirty tonnes of hurtling steel are overcome and burned by a terrible toxic sludge which floods from the shattered vehicle.

The woman is eventually identified as Alice Hickson, a journalist, and the woman who provided the ID, a literary editor called Manikandan Lal, is flying home from holiday to give further background to her friend’s disappearance and death. ‘Kandi’ Lal fails to make her appointment with Gilchrist, however, and soon the police team realise that they may be hunting for a second victim of whoever killed Alice Hickson. Gilchrist’s partner, DS Jessie Janes has problems of own, which are become nagging distractions from her professional duties. As if it were not bad enough to learn that her junkie mother has been murdered by a family member, Jessie is faced with the heartbreaking task of explaining to her son that an operation to correct his deafness has been cancelled permanently.

The woman is eventually identified as Alice Hickson, a journalist, and the woman who provided the ID, a literary editor called Manikandan Lal, is flying home from holiday to give further background to her friend’s disappearance and death. ‘Kandi’ Lal fails to make her appointment with Gilchrist, however, and soon the police team realise that they may be hunting for a second victim of whoever killed Alice Hickson. Gilchrist’s partner, DS Jessie Janes has problems of own, which are become nagging distractions from her professional duties. As if it were not bad enough to learn that her junkie mother has been murdered by a family member, Jessie is faced with the heartbreaking task of explaining to her son that an operation to correct his deafness has been cancelled permanently. Detective Inspector characters have become a staple in British crime fiction, mainly because their position gives them a complete overview of what is usually a murder case, while also allowing them to “get their hands dirty” and provide us readers with action and excitement. So, the concept has become a genre within a genre, and there must be enough fictional DCIs and DIs to fill a conference hall. This said, the stories still need to be written well, and Frank Muir (right) has real pedigree. This latest book will disappoint neither Andy Gilchrist’s growing army of fans nor someone for whom reading The Killing Connection is by way of an introduction.

Detective Inspector characters have become a staple in British crime fiction, mainly because their position gives them a complete overview of what is usually a murder case, while also allowing them to “get their hands dirty” and provide us readers with action and excitement. So, the concept has become a genre within a genre, and there must be enough fictional DCIs and DIs to fill a conference hall. This said, the stories still need to be written well, and Frank Muir (right) has real pedigree. This latest book will disappoint neither Andy Gilchrist’s growing army of fans nor someone for whom reading The Killing Connection is by way of an introduction.

In the icy Scottish dawn of 16th April 1746, the last battle to be fought on British soil was just hours away. The soldiers of the Hanoverian army of William Duke of Cumberland were shaking off their brandy-befuddled sleep, caused by extra rations to celebrate the Duke’s birthday. Just a mile or two distant, the massed ranks of the Scottish clans loyal to Charles Edward Stuart, the Young Pretender, were shivering in their plaid cloaks, wet and exhausted after an abortive night march to attack the enemy.

In the icy Scottish dawn of 16th April 1746, the last battle to be fought on British soil was just hours away. The soldiers of the Hanoverian army of William Duke of Cumberland were shaking off their brandy-befuddled sleep, caused by extra rations to celebrate the Duke’s birthday. Just a mile or two distant, the massed ranks of the Scottish clans loyal to Charles Edward Stuart, the Young Pretender, were shivering in their plaid cloaks, wet and exhausted after an abortive night march to attack the enemy. The Well Of The Dead is a winning combination of several different elements. It’s a brisk and authentic police procedural, written by someone who clearly knows how a major enquiry works. For those who enjoy a costume drama with a dash of buried treasure, there is interest a-plenty. Military history buffs will admire the broad sweep of how Allan (right) describes the glorious failure that was the Jacobite rebellion, as well as being gripped by the detailed knowledge of the men who fought and died on that sleet-swept April day in 1746, bitter both in the grim weather conditions and what would prove to be a disastrous legacy for the Scottish Highlanders and their proud culture.

The Well Of The Dead is a winning combination of several different elements. It’s a brisk and authentic police procedural, written by someone who clearly knows how a major enquiry works. For those who enjoy a costume drama with a dash of buried treasure, there is interest a-plenty. Military history buffs will admire the broad sweep of how Allan (right) describes the glorious failure that was the Jacobite rebellion, as well as being gripped by the detailed knowledge of the men who fought and died on that sleet-swept April day in 1746, bitter both in the grim weather conditions and what would prove to be a disastrous legacy for the Scottish Highlanders and their proud culture. This is the second outing for Clive Allan’s Detective Inspector Neil Strachan and, as in the first book in the series, The Drumbeater, past and present collide. Glenruthven, a tiny community in the Scottish Highlands, is dominated by its distillery. When the owner, Hugh Fraser is murdered alongside his wife, the village is shattered at the thought of there being a killer in their midst.

This is the second outing for Clive Allan’s Detective Inspector Neil Strachan and, as in the first book in the series, The Drumbeater, past and present collide. Glenruthven, a tiny community in the Scottish Highlands, is dominated by its distillery. When the owner, Hugh Fraser is murdered alongside his wife, the village is shattered at the thought of there being a killer in their midst. As Strachan and his police partner DS Holly Anderson set about finding the killer, they discover that the man they suspect of the double murder is obsessed with his own ancestry, and believes that he is related to a Jacobite soldier who, like so many of his fellow rebels, was slain on the bloody battlefield of Culloden on 16th April 1746.

As Strachan and his police partner DS Holly Anderson set about finding the killer, they discover that the man they suspect of the double murder is obsessed with his own ancestry, and believes that he is related to a Jacobite soldier who, like so many of his fellow rebels, was slain on the bloody battlefield of Culloden on 16th April 1746. Clive Allan (right) is a former police officer of thirty years’ service, and is also a keen aficionado of his country’s military history. This mixture of experience and passion combines to create a novel which will blend the lure of momentous events of the past with the gritty reality of modern policing.

Clive Allan (right) is a former police officer of thirty years’ service, and is also a keen aficionado of his country’s military history. This mixture of experience and passion combines to create a novel which will blend the lure of momentous events of the past with the gritty reality of modern policing.

As the pathologists – literally – piece together the evidence they conclude that the shattered remains in the tree is that all that is left of Bill Chalmers, a copper who was not so much bent as tangled and doubled up on himself. After surviving a jail sentence for his misdeeds, he used his connections and his wits to found a drug rehabilitation charity, which drew immense support from the community.

As the pathologists – literally – piece together the evidence they conclude that the shattered remains in the tree is that all that is left of Bill Chalmers, a copper who was not so much bent as tangled and doubled up on himself. After surviving a jail sentence for his misdeeds, he used his connections and his wits to found a drug rehabilitation charity, which drew immense support from the community.