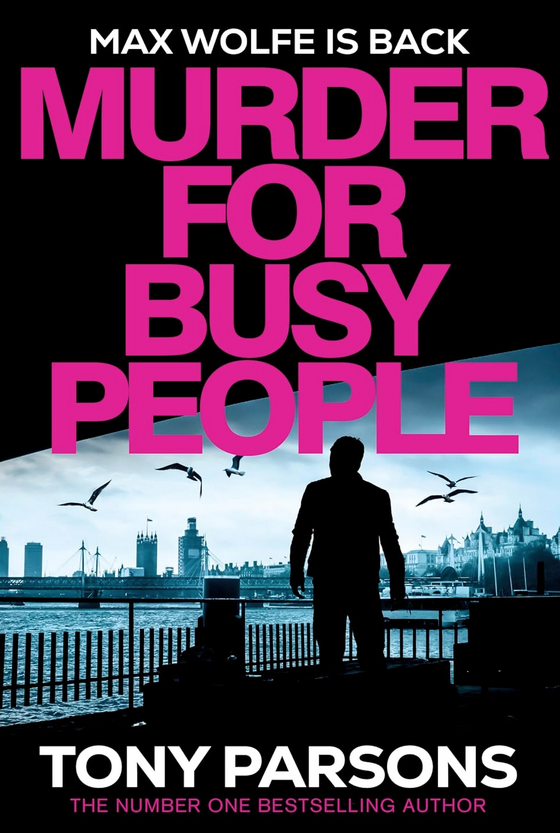

The good news is that DS Max Wolfe is back, and the even better news is that, after a long absence, our man is in very good form. As a young uniformed copper, only days out of Hendon Police College, Wolfe was first on the scene at a safe heist in a palatial London villa. All he found was a gaping hole in the wall, two corpses – and a young woman called Emma Moon, a girlfriend of the mobsters who committed the heist. Wolfe put the cuffs on her, she was tried, convicted, and served a long jail term, during which her troubled son committed suicide. Never once, during the whole process, did she utter a word about those who profited from the robbery. Now, she is out, suffering with terminal cancer, but on a ice cold revenge mission to kill as many of her former associates as she can in the brief time she has left.

Old Max Wolfe hands will know that there is an autobiographical strand running through the novels. Parsons’ breakthrough book was Man and Boy, an account of a male single parent. Here, Wolfe brings up his daughter Scout, rather than a son. Both Wolfe and Parsons are lovers of a dog called Stan, and it was sad to see an RIP notice to the real Stan in the frontispiece of this novel. Max Wolfe lives within sight, sound and smell of the historic meat market known as Smithfield, for centuries the beating heart of a country that loves beef, pork and lamb. Parsons may not have known, when this book was signed off to the printers, that the death knell would be sounded on this historic site. It will, no doubt, be demolished and something trite and anodyne built in its place. This is a purely personal paragraph, as Parsons doesn’t preach, but I think London is gone for us now: pubs are closing at an alarming rate, institutions like the iconic chop house Simpsons of Cornhill lie empty, derelict and vandalised. Philip Larkin was right when he wrote, “And that will be England gone.”

Wolfe juggles several criminal – and personal – issues. He knows that a group of Jack-The-Lad firearms officers have a flat where they abuse young women, wrongly arrested when they flash their warrant cards. The murder of a young woman of the streets, Suzanne, seems unsolvable. On a personal level, he struggles to keep tabs on Scout, his twelve-year-old daughter. She is wilful, disobedient, but highly intelligent. Every single second while he is working, he is worried about where she is, and what she is doing. One by one, the foot soldiers of the heist succumb, each apparently, to natural causes. Wolfe does, in the end, unmask the killer, but more by accident that intention.

Apart from being a gripping read from the first page to the last, this novel is remarkably prescient. I believe that there are many months between the final edition of a book being sent to the printers, and its appearance on bookshop shelves. Parsons weaves two very recent issues into the warp and wedt of his novel. One is a subtle and reflective elegy on Smithfield and its sanguinary history. Just weeks ago, an enquiry released its findings into the killing of a London criminal at the hands of firearms officers. Parsons lets us know, in excruciating detail, the hell that descends on any officer who fires a fatal shot.

Max Wolfe is both convincing and endearing. He doesn’t always get things right. Here, his judgment of Sarah Moon veers from spot-on to plain-wrong (and back again) several times. For all that certain critics and reviewers turn up their noses at Tony Parsons because of his political views, and the newspapers he has written for, the last pages of this book reveal what I have known ever since I met the man at a publishers’ party. He is observant, fiercely honest, and a deeply sensitive writer. Max Wolfe may be only marginally autobiographical but, like his creator, he only dances to the tunes he hears in his own head, and not those streamed in from elsewhere. Murder For Busy People will be published by Century on 2nd January.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

Durnie’s plot trajectory which, thus far, had seemed on a fairly steady arc, spins violently away from its course when he reveals a totally unexpected relationship between two of the principle players in this drama, and this forces Cunningham into drastic action.

Alan Parks (left) introduced us to Glasgow cop

Alan Parks (left) introduced us to Glasgow cop

This is not a crime novel in the traditional sense, and it certainly isn’t a police procedural, despite Mickey’s profession. The plot partly involves the search for someone who is killing young women who have been forced into prostitution to feed their drug habit but, although this is resolved, it is eventually incidental to the main thrust of the novel.

This is not a crime novel in the traditional sense, and it certainly isn’t a police procedural, despite Mickey’s profession. The plot partly involves the search for someone who is killing young women who have been forced into prostitution to feed their drug habit but, although this is resolved, it is eventually incidental to the main thrust of the novel. Liz Moore (right) treats Mickey’s search for her sister on two levels: the first, and more obvious one, is a nightmare trip through the squats and shoot-up dens of Kensington in an attempt to find Kacey – a search, find and protect mission, if you will. On a more metaphorical level, the books becomes a journey through Mickey’s own past in the quest for a more elusive truth involving her family and her own identity.

Liz Moore (right) treats Mickey’s search for her sister on two levels: the first, and more obvious one, is a nightmare trip through the squats and shoot-up dens of Kensington in an attempt to find Kacey – a search, find and protect mission, if you will. On a more metaphorical level, the books becomes a journey through Mickey’s own past in the quest for a more elusive truth involving her family and her own identity.

very so often a book comes along that is so beautifully written and so haunting that a reviewer has to dig deep to even begin to do it justice. Shamus Dust by Janet Roger is one such. The author seems, as they say, to have come from nowhere. No previous books. No hobnobbing on social media. So who is Janet Roger? On her website she says:

very so often a book comes along that is so beautifully written and so haunting that a reviewer has to dig deep to even begin to do it justice. Shamus Dust by Janet Roger is one such. The author seems, as they say, to have come from nowhere. No previous books. No hobnobbing on social media. So who is Janet Roger? On her website she says: o, what exactly is Shamus Dust? Tribute? Homage? Pastiche? ‘Nod in the direction of..’? ‘Strongly influenced by ..’? Pick your own description, but I know that if I were listening to this as an audio book, narrated in a smoky, world-weary American accent, I could be listening to the master himself. The phrase ‘Often imitated, never bettered’ is an advertising cliché and, of course, Janet Roger doesn’t better Chandler, but she runs him pretty damn close with a taut and poetic style that never fails to shimmer on the page.

o, what exactly is Shamus Dust? Tribute? Homage? Pastiche? ‘Nod in the direction of..’? ‘Strongly influenced by ..’? Pick your own description, but I know that if I were listening to this as an audio book, narrated in a smoky, world-weary American accent, I could be listening to the master himself. The phrase ‘Often imitated, never bettered’ is an advertising cliché and, of course, Janet Roger doesn’t better Chandler, but she runs him pretty damn close with a taut and poetic style that never fails to shimmer on the page.

ig mistake. Councillor Drake underestimates Newman’s intelligence and natural scepticism. Our man uncovers a homosexual vice ring, a cabal of opportunists who stand to make millions by rebuilding a shattered city, and an archaeological discovery which could halt their reconstruction bonanza.

ig mistake. Councillor Drake underestimates Newman’s intelligence and natural scepticism. Our man uncovers a homosexual vice ring, a cabal of opportunists who stand to make millions by rebuilding a shattered city, and an archaeological discovery which could halt their reconstruction bonanza.

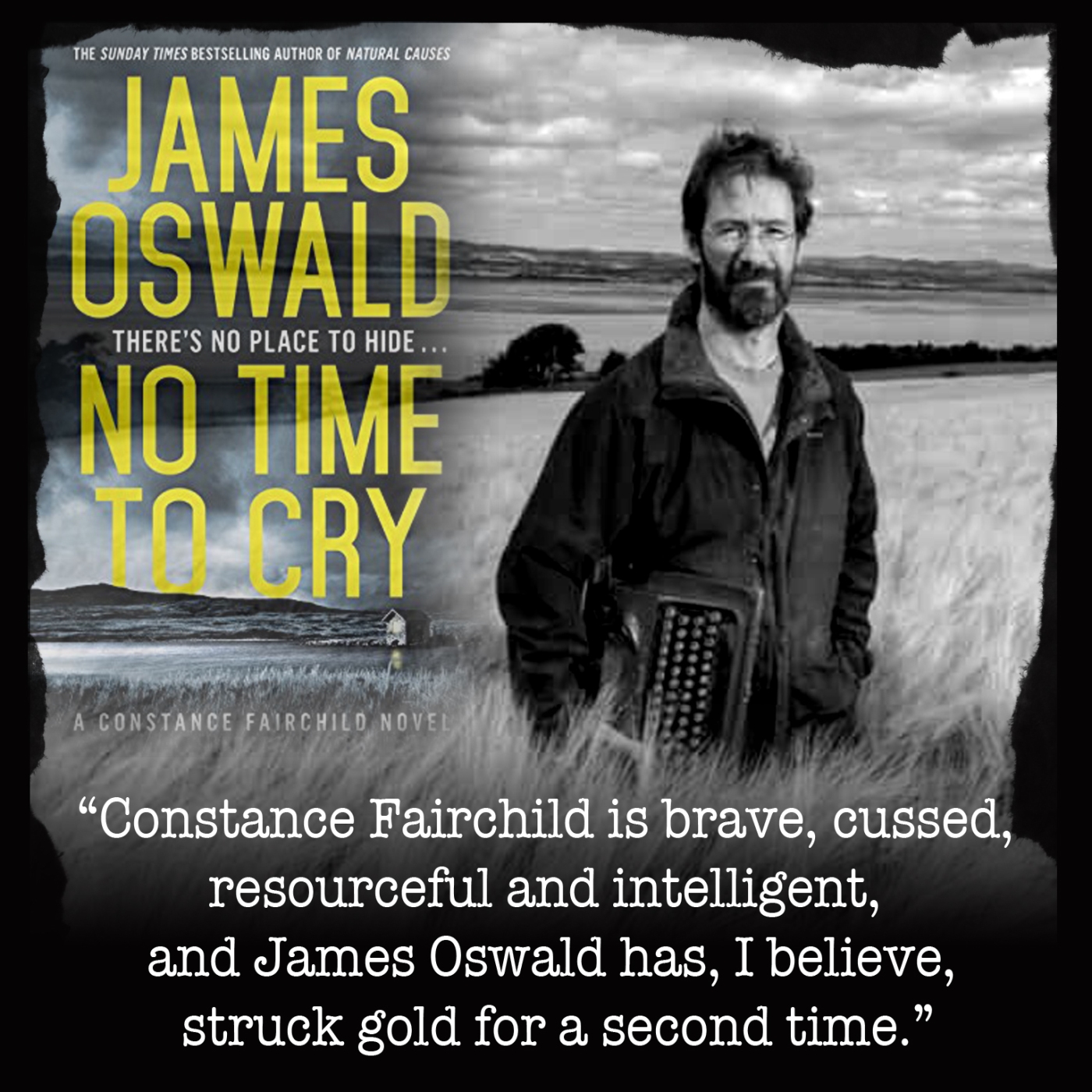

James Oswald’s Tony McLean has not met with a Reichenbach Falls accident, but at the end of

James Oswald’s Tony McLean has not met with a Reichenbach Falls accident, but at the end of

With that grim discovery acting as a starting pistol, debut author Robert Scragg (left) starts a middle-distance race to discover who murdered Natasha Barclay. For she is the person, identified by simply reading the opened mail strewn around the tomb-like flat, and checking rental records, whose hand lies in the freezer drawer.

With that grim discovery acting as a starting pistol, debut author Robert Scragg (left) starts a middle-distance race to discover who murdered Natasha Barclay. For she is the person, identified by simply reading the opened mail strewn around the tomb-like flat, and checking rental records, whose hand lies in the freezer drawer. If ever there were an single implausible plot device, it might be the premise that a suburban London flat, complete with a severed hand sitting quietly in a freezer compartment, could remain untouched, unvisited and unnoticed for over thirty years. It is, however, a tribute to Robert Scragg’s skill as a storyteller that this oddity was so easily forgotten. The dialogue, the twists and turns of the plot, and the absolute credibility of the characters swept me along on the ride. Porter and Styles have made an impressive debut, and the author may well have elbowed them into that crowded room full of other fictional police partners. They are all out there; Bryant & May, Zigic & Ferrera, Rizzoli & Isles, Wolfe & Goodwin, Morse & Lewis, Jordan & Hill, Kiszka and Kershaw – watch out, you have company!

If ever there were an single implausible plot device, it might be the premise that a suburban London flat, complete with a severed hand sitting quietly in a freezer compartment, could remain untouched, unvisited and unnoticed for over thirty years. It is, however, a tribute to Robert Scragg’s skill as a storyteller that this oddity was so easily forgotten. The dialogue, the twists and turns of the plot, and the absolute credibility of the characters swept me along on the ride. Porter and Styles have made an impressive debut, and the author may well have elbowed them into that crowded room full of other fictional police partners. They are all out there; Bryant & May, Zigic & Ferrera, Rizzoli & Isles, Wolfe & Goodwin, Morse & Lewis, Jordan & Hill, Kiszka and Kershaw – watch out, you have company!