If crime writers could win bravery awards, then Joseph Knox would certainly awarded the Military Medal, if not DSO or higher. Having written three well-received novel featuring flawed Manchester copper Aidan Waits (click for reviews), he killed him off, albeit ambiguously, and has now written a novel called True Crime Story. First up, a kind of spoiler, but it has to be done. The key is in the third word of the title. The people who are central to this book never existed. The victim, a university student called Zoe Nolan exists only in Joseph Knox’s head. Such is the authentic tone of the writing, I had to do a quick internet search, but Zoe Nolan never lived. She never disappeared, and those who make up the narrative – her family and friends – are equally imaginary.

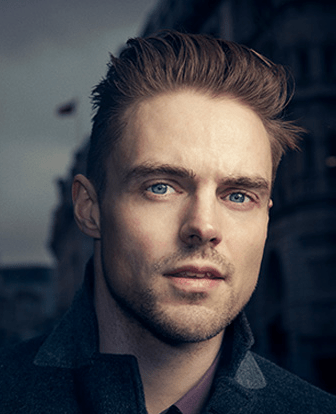

If you can get your head around the idea, Knox (left) plays himself here and the book is a series of statements, made to a fellow author by a cast of characters who were part of Zoe’s life. Initially, we have her parents, her twin sister, and an array of other young people who were part of her life prior to her disappearance after a night clubbing in Manchester, but as Zoe Nolan is gradually transformed into someone with a huge bag of secrets slung over her shoulder, more voices are added to the account.

If you can get your head around the idea, Knox (left) plays himself here and the book is a series of statements, made to a fellow author by a cast of characters who were part of Zoe’s life. Initially, we have her parents, her twin sister, and an array of other young people who were part of her life prior to her disappearance after a night clubbing in Manchester, but as Zoe Nolan is gradually transformed into someone with a huge bag of secrets slung over her shoulder, more voices are added to the account.

The beauty of this narrative device is that we have no idea who is telling the truth, or whose words are reliable. We may even be reading a clever defensive account from the person responsible for her demise. The skill, of course, is making each statement equally plausible, even though some of the statements are contradictory. Knox sets us a challenge. We are judge and jury. Who is credible? Who has invented a tale to cover up their own complicity in events? Or, even more extreme, is there someone talking who isn’t the person they claim to be?

As clever as this is, Knox has to make the most of it, as it will only work once. It makes the reader do the work in a way that a standard crime mystery does not. In a regulation police procedural, the investigating officer takes in information, and he or she makes judgments on our behalf. We follow their reasoning and, although they sometimes make mistakes, we rarely see the error before they do.

The statements made by the ‘witnesses’ give us an overview – albeit imperfect, given that we don’t know who to trust – of the hours leading up to Zoe’s disappearance, and the months and years which led up to a promising young singer being rejected by the Royal Northern Collegee of Music and having to settle for a less prestigious place at Manchester University.

The statements made by the ‘witnesses’ give us an overview – albeit imperfect, given that we don’t know who to trust – of the hours leading up to Zoe’s disappearance, and the months and years which led up to a promising young singer being rejected by the Royal Northern Collegee of Music and having to settle for a less prestigious place at Manchester University.

Just when you think things couldn’t become more complicated, they do. Having got used to the concept that the Joseph Knox in the book isn’t the real Joseph Knox ( a kind of Schrödinger’s Author, if you will), and there never was an Evelyn Mitchell with whom he corresponds, the flesh and blood Joseph Knox, who I have met and spoken to, has his alter ego throw more spanners into the narrative, by way of a ‘Publisher’s Note’ saying that as this (the paperback copy) is the second edition of the book, since the first edition ‘new information’ unavailable at the time the first book went to the printers, has been added ‘for clarity’.

So what happens in the end? Of course I am not going to tell you, but unless they cheat and read the book from the back, I think it will be a clever person who predicts the outcome. This uses one of the cleverest narrative devices I have ever come across, and is an intriguing read. The problem is that anyone with an ounce of curiosity is going to Google Zoe Nolan and will, within seconds, the conjuror’s rabbit has not so much escaped from the hat, but been skinned, jointed and put in the pot for dinner.

True Crime Story came out in hardback and Kindle in June 2021 and this paperback version will be out in March. It is published by Penguin.

In a sappingly hot Indian Summer in central London, Dr John Watson is sent – by a relative he hardly remembers – a mysterious tin box which has no key, and no apparent means by which it can be opened. Watson and his companion Sherlock Holmes have become temporarily estranged, not because of any particular antipathy, but more because the investigations which have brought them so memorably together have dwindled to a big fat zero.

In a sappingly hot Indian Summer in central London, Dr John Watson is sent – by a relative he hardly remembers – a mysterious tin box which has no key, and no apparent means by which it can be opened. Watson and his companion Sherlock Holmes have become temporarily estranged, not because of any particular antipathy, but more because the investigations which have brought them so memorably together have dwindled to a big fat zero. But then, in the space of a few hours, Watson shows his mysterious box to his house-mate, and the door of 221B Baker Street opens to admit two very different visitors. One is a young Roman Catholic novice priest from Cambridge who is worried about the disappearance of a young woman he has an interest in, and the second is a voluptuous conjuror’s assistant with a very intriguing tale to tell. The conjuror’s assistant, Madam Ilaria Borelli is married to one stage magician, Dario ‘The Great’ Borelli, but is the former lover of his bitter rival, Santo Colangelo. Are the two showmen trying to kill each other for the love of Ilaria? Have they doctored each other’s stage apparatus to bring about disastrous conclusions to their separate performances?

But then, in the space of a few hours, Watson shows his mysterious box to his house-mate, and the door of 221B Baker Street opens to admit two very different visitors. One is a young Roman Catholic novice priest from Cambridge who is worried about the disappearance of a young woman he has an interest in, and the second is a voluptuous conjuror’s assistant with a very intriguing tale to tell. The conjuror’s assistant, Madam Ilaria Borelli is married to one stage magician, Dario ‘The Great’ Borelli, but is the former lover of his bitter rival, Santo Colangelo. Are the two showmen trying to kill each other for the love of Ilaria? Have they doctored each other’s stage apparatus to bring about disastrous conclusions to their separate performances?

The poet Vernon Scannell, himself a veteran of WW2 wrote a haunting poem he called The Great War. The closing lines are:

The poet Vernon Scannell, himself a veteran of WW2 wrote a haunting poem he called The Great War. The closing lines are: In her 2014 novel Those Measureless Fields she began her own personal exploration of what happened to the men and families who had to pick up the pieces of their lives after the Armistice. She followed this in 2019 with what was, for, me one of the books of the year,

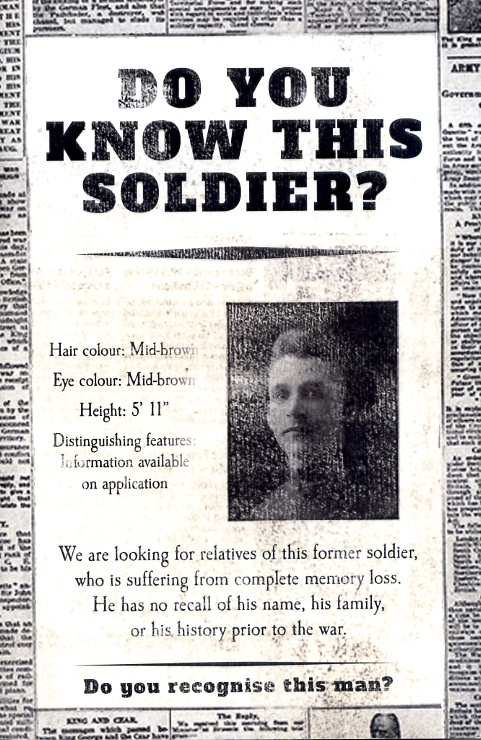

In her 2014 novel Those Measureless Fields she began her own personal exploration of what happened to the men and families who had to pick up the pieces of their lives after the Armistice. She followed this in 2019 with what was, for, me one of the books of the year,  At a rehabilitation centre in the Lake District, Haworth tries to find the key that will unlock Adam’s memory. James and his boss, Alec Shepherd, take a bold decision. They release a photograph of Adam, and what little they know of him, to the national press. This triggers a wave of mothers, wives and sisters who yearn for the impossible – a virtual resurrection of their lost son, husband and brother. From the tragic queue of broken hearted souls, three women seem to be the most convincing. They are Celia Daker, who believes that Adam is her missing son, Robert, Anna Mason, a young wife who dares to dream that she is no longer a widow, and Lucy Vickers a sister who is now bringing up the children of her lost brother.

At a rehabilitation centre in the Lake District, Haworth tries to find the key that will unlock Adam’s memory. James and his boss, Alec Shepherd, take a bold decision. They release a photograph of Adam, and what little they know of him, to the national press. This triggers a wave of mothers, wives and sisters who yearn for the impossible – a virtual resurrection of their lost son, husband and brother. From the tragic queue of broken hearted souls, three women seem to be the most convincing. They are Celia Daker, who believes that Adam is her missing son, Robert, Anna Mason, a young wife who dares to dream that she is no longer a widow, and Lucy Vickers a sister who is now bringing up the children of her lost brother.

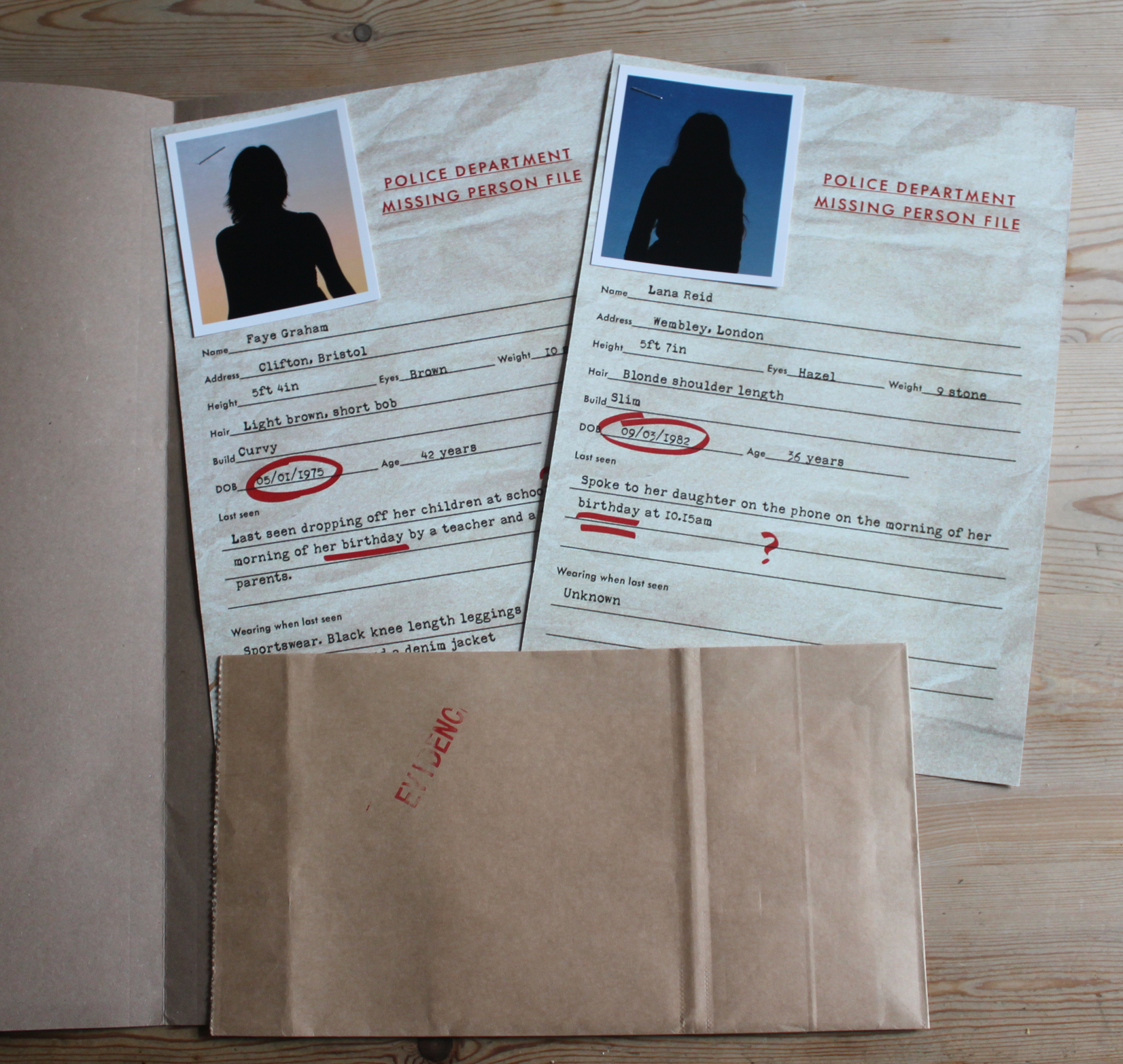

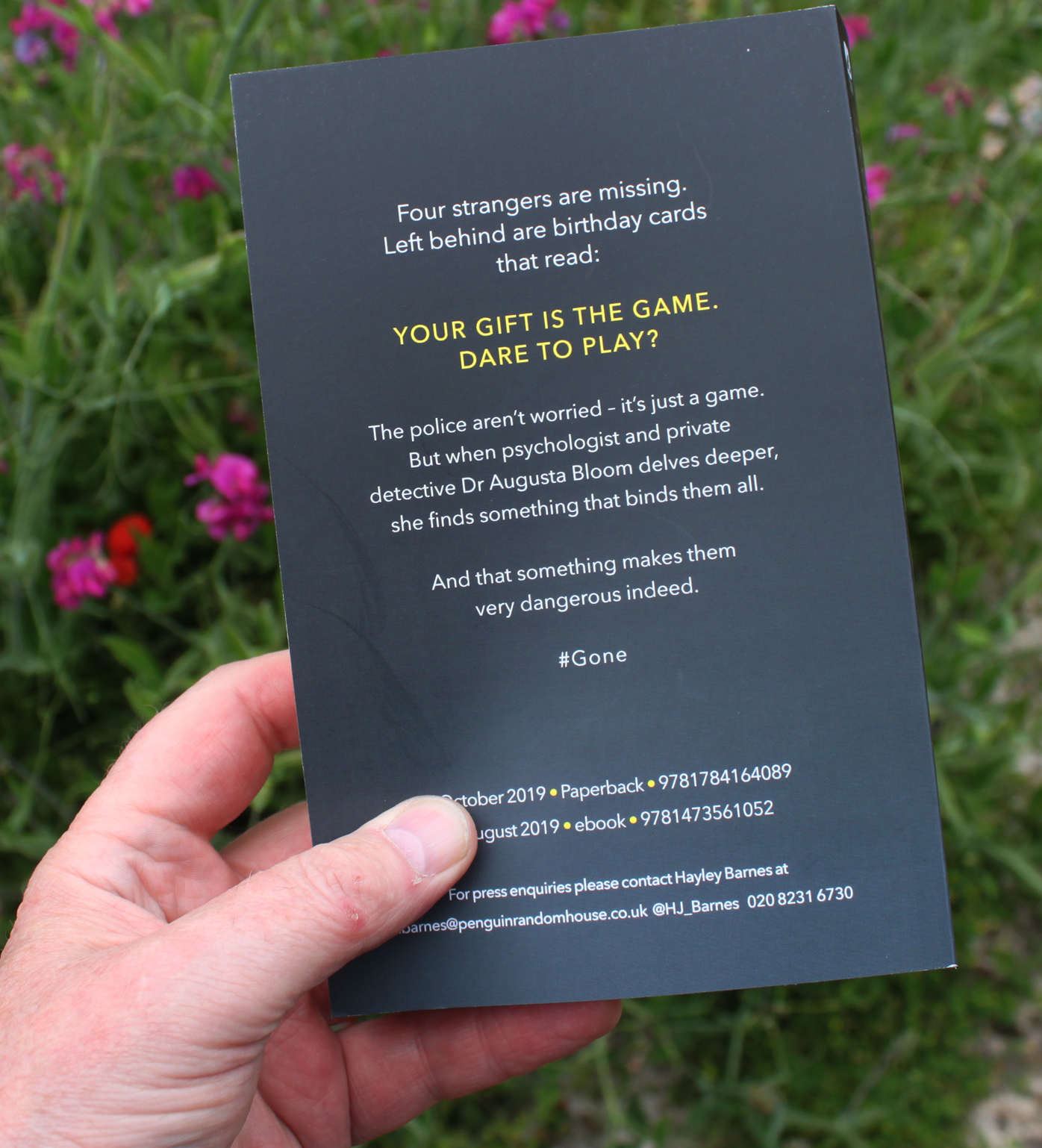

he creative folk at Penguin Random House are certainly pushing the boat out in support of Gone, a new psychological thriller and the debut novel by former police psychologist Leona Deakin.

he creative folk at Penguin Random House are certainly pushing the boat out in support of Gone, a new psychological thriller and the debut novel by former police psychologist Leona Deakin.