Mark Billingham’s perpetually disgruntled and discomforted London copper DI Tom Thorne returns in The Killing Habit for another three way battle. Three way? Yes, of course, because Thorne and his resolute allies sit on their stools in one corner of the triangular boxing ring, while in the blue corner are his politically correct bosses. In the red corner, of course, are the various chancers, petty and not-so-petty crooks who challenge the law on a daily basis.

The Thorne novels have a recurring cast list. As Salvatore Albert Lombino, aka Ed McBain said, quoting a 1917 popular song, “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here!” Indeed they are. Its members include Helen, Tom Thorne’s long suffering partner plus little boy Alfie, and the bizarrely tattooed and pierced Mancunian pathologist Phil Hendricks. We have Nicola Tanner the police officer scarred by the murder of her alcoholic partner, Susan, and the perpetually cautious DCI Russell Brigstocke. Between them, they pursue two killers; one who murders losers-in-the-Game-of-Life on the periphery of a drugs gang, and another who seems to be targeting lonely women via a match-making service.

The Thorne novels have a recurring cast list. As Salvatore Albert Lombino, aka Ed McBain said, quoting a 1917 popular song, “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here!” Indeed they are. Its members include Helen, Tom Thorne’s long suffering partner plus little boy Alfie, and the bizarrely tattooed and pierced Mancunian pathologist Phil Hendricks. We have Nicola Tanner the police officer scarred by the murder of her alcoholic partner, Susan, and the perpetually cautious DCI Russell Brigstocke. Between them, they pursue two killers; one who murders losers-in-the-Game-of-Life on the periphery of a drugs gang, and another who seems to be targeting lonely women via a match-making service.

It’s a staple of serial killer crime fiction that the bad guy starts out as a youngster by pulling wings off flies or torturing hamsters before graduating to ever darker deeds. Either that, or he is the victim of some terrible childhood trauma which poisons his view of humanity. I say ‘he’ and realise that I may be risking the wrath of the Equal Opportunities Police here, but I don’t recall reading a novel about female mass murderers. They may be out there. Numbered among their ranks may be homicidal Two Spirit Persons or Gender Fluid Otherkins. I do not know. If I have offended any potential killers by using the wrong pronoun, please accept my (almost) sincere apologies.

But I digress. Billingham puts Thorne on the trail of a serial killer – of cats. Why on earth? Two reasons. One is that nothing inflames the fury of Middle England like the killing of domestic animals. The debate that compares this crime with that of the murder of humans is for another day, but Billingham recognises that we are more likely to become incandescent over the death of a domestic pet than the death of a child. The second reason I have already suggested. If someone is waging a covert war on cats, is this just a prelude to something far, far worse? Indeed, it seems so. A succession of women meet their deaths at the hands of a killer who has hacked into the database of Made In Heaven, a low-rent match-making website.

Billingham gives us a parallel plot which eventually converges with the main story. A shadowy but powerful criminal organisation smuggles addictive synthetic drugs into British prisons. The recipients, grateful at the time, are eventually released into the wider world owing the gang an impossible amount of money, repayable only by becoming foot soldiers of the gang itself. An elderly woman, known only as “The Duchess” plays Postman Patricia in this deadly cycle of addiction and dependence and, when her role as amiable ‘auntie’ visiting prisoners is exposed, the connection between the drug scam and the dating killer is made.

As with every Mark Billingham novel, The Killing Habit is incisively written, impeccably authentic as a police procedural and, above all, totally human. No character walks onto the stage without their weaknesses and their frailties becoming exposed in the icy blue of the spotlight. We are not reading about cardboard cut-out people here: they are real, fallible and convincing. They may even be living a couple of doors down from you.

Just when you think that he has provided all the answers to the complex plot, and the characters are, to quote the only bit of Milton I can remember from ‘A’ Level, “calm of mind and all passion spent,” Billingham (right) provides a breathtaking epilogue which, in addition to turning my preconception on its head, (feel free to add your own metaphor) bites you on the bum, punches you in the gut, hits you over the head with a piece of four by two, takes the wind out of your sails and grabs you by the short-and-curlies. Hopefully recovering from this multiple assault, you will be hard pushed to disagree with me that this is a brilliant crime thriller written by a master storyteller at the very top of his game.

Just when you think that he has provided all the answers to the complex plot, and the characters are, to quote the only bit of Milton I can remember from ‘A’ Level, “calm of mind and all passion spent,” Billingham (right) provides a breathtaking epilogue which, in addition to turning my preconception on its head, (feel free to add your own metaphor) bites you on the bum, punches you in the gut, hits you over the head with a piece of four by two, takes the wind out of your sails and grabs you by the short-and-curlies. Hopefully recovering from this multiple assault, you will be hard pushed to disagree with me that this is a brilliant crime thriller written by a master storyteller at the very top of his game.

The Killing Habit is published by Litte, Brown and will be available on 14th June. For a review of the previous Tom Thorne novel, click the link to Love Like Blood.

But he has, as far as is possible, moved on. He has an unexpected family in the form of a daughter from an early relationship, and he keeps his chin up and his eyes bright. Because to do otherwise would mean self destruction, and he owes the physically absent but ever-present spirit of Derryn that much. His world, however, and such stability as he has been able to build into it, is rocked on its axis when a woman turns up at a West End police station claiming to be his wife. Derryn. Dead and buried these nine years. Her fragile remains consigned to the earth. He sees the woman through a viewing screen at the police station and he is astonished. In front of him sits his late wife, the love of his life, and the woman for whom he has shed nine years of tears.

But he has, as far as is possible, moved on. He has an unexpected family in the form of a daughter from an early relationship, and he keeps his chin up and his eyes bright. Because to do otherwise would mean self destruction, and he owes the physically absent but ever-present spirit of Derryn that much. His world, however, and such stability as he has been able to build into it, is rocked on its axis when a woman turns up at a West End police station claiming to be his wife. Derryn. Dead and buried these nine years. Her fragile remains consigned to the earth. He sees the woman through a viewing screen at the police station and he is astonished. In front of him sits his late wife, the love of his life, and the woman for whom he has shed nine years of tears. So many questions. The answers do come, and the whole journey is great fun – but occasionally nerve racking and full of tension. Tim Weaver (right) has crafted yet another brilliant piece of entertainment, and placed a further brick in the wall built for people who know that there is nothing more riveting, nothing more calculated to shut out the real world and nothing more breathtaking than a good book.

So many questions. The answers do come, and the whole journey is great fun – but occasionally nerve racking and full of tension. Tim Weaver (right) has crafted yet another brilliant piece of entertainment, and placed a further brick in the wall built for people who know that there is nothing more riveting, nothing more calculated to shut out the real world and nothing more breathtaking than a good book.

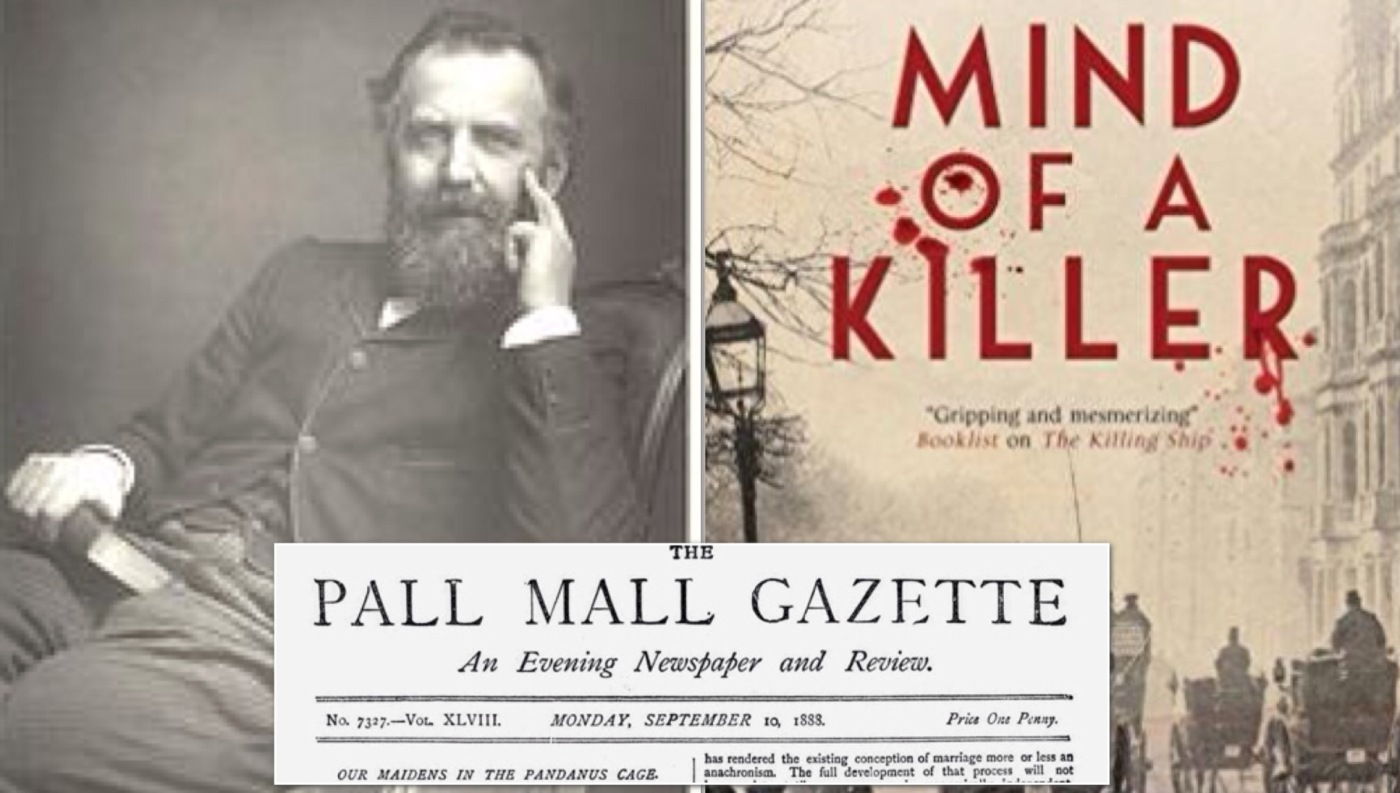

Simon Beaufort provides an exhilarating and madcap journey through the contrasting mileus of Victorian London. We experience gentlemen’s clubs with their subtle ambience of brandy and fine cigars, the visceral stench of low-life pubs and doss houses and the clatter of the hot lead printing presses of a vibrant daily newspaper. Lonsdale – with the assistance of Hulda Friedrichs, a fiercely independent early feminist journalist – painstakingly uncovers a nightmarish plot hatched by scientists who are obsessed with eugenics, and believe that the future of the human race depends on selective breeding and the suppression of ‘the undeserving poor’.

Simon Beaufort provides an exhilarating and madcap journey through the contrasting mileus of Victorian London. We experience gentlemen’s clubs with their subtle ambience of brandy and fine cigars, the visceral stench of low-life pubs and doss houses and the clatter of the hot lead printing presses of a vibrant daily newspaper. Lonsdale – with the assistance of Hulda Friedrichs, a fiercely independent early feminist journalist – painstakingly uncovers a nightmarish plot hatched by scientists who are obsessed with eugenics, and believe that the future of the human race depends on selective breeding and the suppression of ‘the undeserving poor’.

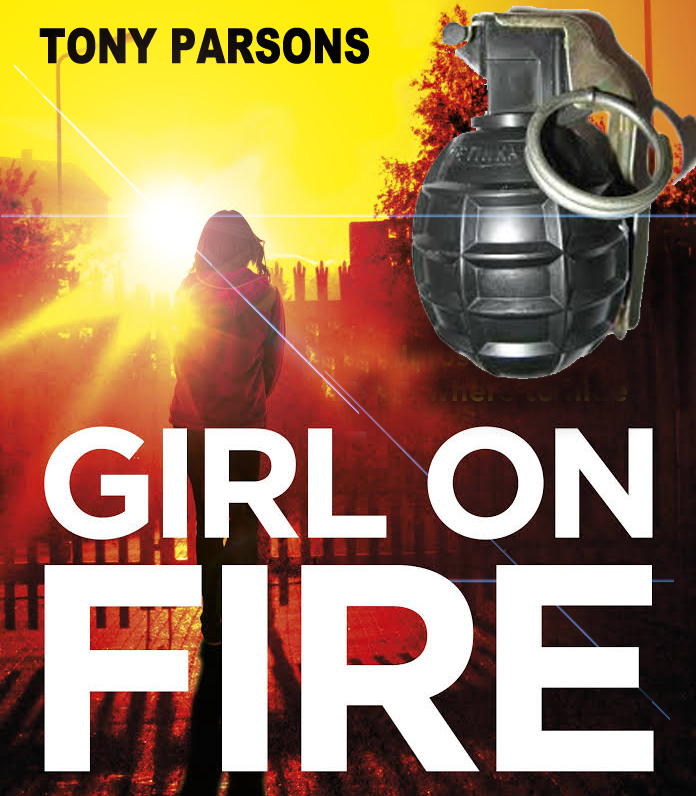

Wolfe survives, and shoulders his way into the hit team which raids a nondescript terraced house in Borodino Street in East London. Their target? To capture two Pakistani brothers who have adapted simple commercially available drones into weapons of terror. Needless to say, the raid does not go according to plan. The lead police officer is shot dead at the outset, by one of the brothers disguised in a niqab. He is eventually shot dead, as is the remaining brother. But there are questions raised about the death of the latter. Was he shot as he was trying to surrender, or was he simply assassinated by a vengeful police marksman? And where are the two ex-Croatian hand grenades which informers say had been sold to the Khan brothers?

Wolfe survives, and shoulders his way into the hit team which raids a nondescript terraced house in Borodino Street in East London. Their target? To capture two Pakistani brothers who have adapted simple commercially available drones into weapons of terror. Needless to say, the raid does not go according to plan. The lead police officer is shot dead at the outset, by one of the brothers disguised in a niqab. He is eventually shot dead, as is the remaining brother. But there are questions raised about the death of the latter. Was he shot as he was trying to surrender, or was he simply assassinated by a vengeful police marksman? And where are the two ex-Croatian hand grenades which informers say had been sold to the Khan brothers? The novel frequently holds you by the hand – no, make that puts you in an arm lock – and takes you to places you would rather not go. Parsons (right) is not someone with a well stocked cupboard full of tea lights, bunches of flowers and anodyne pleas for togetherness. He is not going to link arms with anyone and place these tributes at scenes of murder and carnage. Least of all will he, via Max Wolfe, be tweeting Je Suis Borodino Street any time soon. Some might say that for a humble DC, Max Wolfe certainly seems to get about a bit, but this is an irrelevant criticism, because what he thinks and sees are essential to the story. Wolfe is a a man of deep compassion and perception. Not only is his narrative reliable – it is painfully accurate and candid. Readers have, of course, the option of averting their gaze or thinking about gentle deaths in Cotswold villages, solved by avuncular local bobbies. Those who choose not to turn away from this brutal autopsy of Britain – and specifically London – in 2018 will not, I suggest, feel rejuvenated, life-enhanced or particularly optimistic by the end of this novel. Rather, they will follow the emotional journey of the celebrated wedding guest:

The novel frequently holds you by the hand – no, make that puts you in an arm lock – and takes you to places you would rather not go. Parsons (right) is not someone with a well stocked cupboard full of tea lights, bunches of flowers and anodyne pleas for togetherness. He is not going to link arms with anyone and place these tributes at scenes of murder and carnage. Least of all will he, via Max Wolfe, be tweeting Je Suis Borodino Street any time soon. Some might say that for a humble DC, Max Wolfe certainly seems to get about a bit, but this is an irrelevant criticism, because what he thinks and sees are essential to the story. Wolfe is a a man of deep compassion and perception. Not only is his narrative reliable – it is painfully accurate and candid. Readers have, of course, the option of averting their gaze or thinking about gentle deaths in Cotswold villages, solved by avuncular local bobbies. Those who choose not to turn away from this brutal autopsy of Britain – and specifically London – in 2018 will not, I suggest, feel rejuvenated, life-enhanced or particularly optimistic by the end of this novel. Rather, they will follow the emotional journey of the celebrated wedding guest:

Many people in their sixties – particularly those who are comfortably off – plan ahead for their own funerals. Daytime television programmes are interspersed with advertisements featuring either be-cardiganed senior citizens smugly telling us that they have taken insurance with Coffins ‘R’ Us, or rueful widows plaintively wishing that they had been better prepared for the demise of poor Jack, Barry or Derek. However, it would be unusual to hear that the be-cardiganed senior citizen had died only hours after planning and paying for their own send-off from the world of the living.

Many people in their sixties – particularly those who are comfortably off – plan ahead for their own funerals. Daytime television programmes are interspersed with advertisements featuring either be-cardiganed senior citizens smugly telling us that they have taken insurance with Coffins ‘R’ Us, or rueful widows plaintively wishing that they had been better prepared for the demise of poor Jack, Barry or Derek. However, it would be unusual to hear that the be-cardiganed senior citizen had died only hours after planning and paying for their own send-off from the world of the living. During the story, Horowitz (right) drops plenty of names but, to be fair, the real AH has plenty of names to drop. His CV as a writer is, to say the least, impressive. But just when you might be thinking that he is banging his own drum or blowing his own trumpet – select your favourite musical metaphor – he plays a tremendous practical joke on himself. He is summoned to Soho for a vital pre-production meeting with Steven and Peter (that will be Mr Spielberg and Mr Jackson to you and me), but his star gazing is rudely interrupted by none other than the totally unembarrassable person of Daniel Hawthorne, who barges his way into the meeting to collect Horowitz so that the pair can attend the funeral of Diana Cowper.

During the story, Horowitz (right) drops plenty of names but, to be fair, the real AH has plenty of names to drop. His CV as a writer is, to say the least, impressive. But just when you might be thinking that he is banging his own drum or blowing his own trumpet – select your favourite musical metaphor – he plays a tremendous practical joke on himself. He is summoned to Soho for a vital pre-production meeting with Steven and Peter (that will be Mr Spielberg and Mr Jackson to you and me), but his star gazing is rudely interrupted by none other than the totally unembarrassable person of Daniel Hawthorne, who barges his way into the meeting to collect Horowitz so that the pair can attend the funeral of Diana Cowper.

So, when Gabriel answers the door bell one day only to behold the wedge-shaped and granite faced personage of Farrelly – chauffeur, enforcer and general gofer for Frank Parr – he is led, like a naughty boy tweaked by his ear, to Parr’s sumptious office building. To say that Parr – now a respectable media mogul – has something of a history, is rather like saying that Vlad The Impaler was someone of interest to Amnesty International. Parr made his money – loads of it, and of the distinctly dirty variety – by publishing magazines which were not so much Top Shelf as stacked in the stratosphere miles above the earth’s surface.

So, when Gabriel answers the door bell one day only to behold the wedge-shaped and granite faced personage of Farrelly – chauffeur, enforcer and general gofer for Frank Parr – he is led, like a naughty boy tweaked by his ear, to Parr’s sumptious office building. To say that Parr – now a respectable media mogul – has something of a history, is rather like saying that Vlad The Impaler was someone of interest to Amnesty International. Parr made his money – loads of it, and of the distinctly dirty variety – by publishing magazines which were not so much Top Shelf as stacked in the stratosphere miles above the earth’s surface. “For a while, I wandered the streets of Soho, as I had on the day I’d first visited forty years ago. Doorways whispered to me and ghosts looked down from high windows.”

“For a while, I wandered the streets of Soho, as I had on the day I’d first visited forty years ago. Doorways whispered to me and ghosts looked down from high windows.”

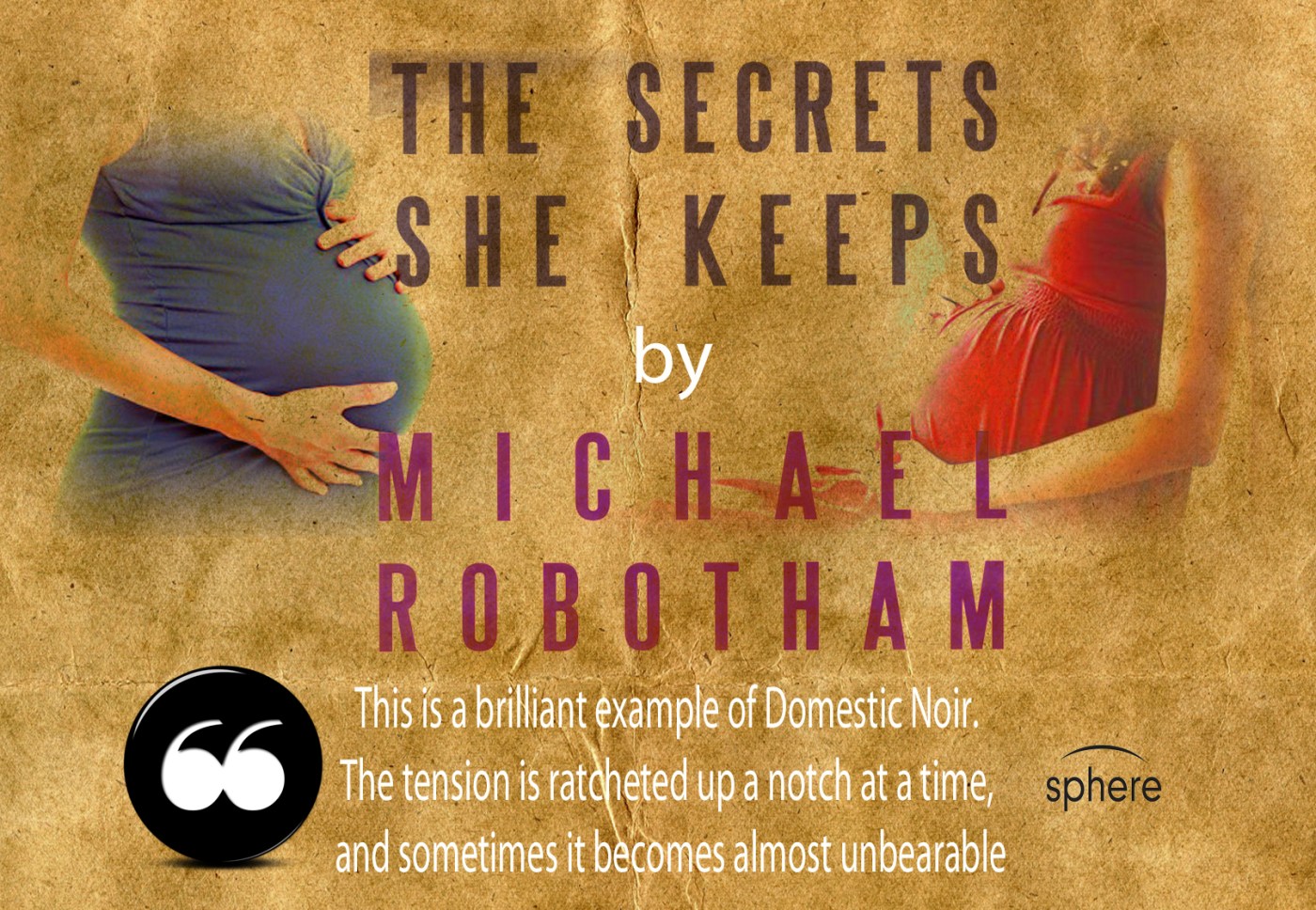

Agatha Fyfle works for peanuts in a ‘Village’ supermarket but Mr Patel, her boss, is not the kind of man to be offering generous maternity leave. He is so tight that he once docked her pay for putting the wrong price on a tin of peaches. The father of her baby is far, far away on a Royal Navy ship patrolling the Indian Ocean, chasing Somali pirates. Despite her nothing job and the desperate ordinariness of her life, Agatha has her imagination and her dreams:

Agatha Fyfle works for peanuts in a ‘Village’ supermarket but Mr Patel, her boss, is not the kind of man to be offering generous maternity leave. He is so tight that he once docked her pay for putting the wrong price on a tin of peaches. The father of her baby is far, far away on a Royal Navy ship patrolling the Indian Ocean, chasing Somali pirates. Despite her nothing job and the desperate ordinariness of her life, Agatha has her imagination and her dreams:

Charles Harris (right), a best-selling non-fiction author and writer-director for film and television sets in train a disastrous serious of mishaps, each of which stems from Kati’s ostensibly harmless error. Too exhausted from her daily grind making sure that Every Little Helps at everyone’s favourite supermarket, she sends her hapless son, Liam, off to the cashpoint, armed with her debit card and its vital PIN. Sadly, Liam never makes it home with the cash, the pizza guy remains unpaid, and Kati Glass is pitched into a nightmare.

Charles Harris (right), a best-selling non-fiction author and writer-director for film and television sets in train a disastrous serious of mishaps, each of which stems from Kati’s ostensibly harmless error. Too exhausted from her daily grind making sure that Every Little Helps at everyone’s favourite supermarket, she sends her hapless son, Liam, off to the cashpoint, armed with her debit card and its vital PIN. Sadly, Liam never makes it home with the cash, the pizza guy remains unpaid, and Kati Glass is pitched into a nightmare. Trying to find out who stabbed Liam Glass is Detective Constable Andy Rackham. He is a walking tick-box of all the difficulties faced by an ambitious copper trying to please his bosses while being a supportive husband and father. The third member of this unholy trinity is Jamila Hasan, an earnest politician of Bengali origin who senses that the attack might be just the campaign platform she needs to ensure that she is re-elected. But what if Liam’s attackers are from her own community? Sadly, in her efforts to gain credibility on the street, Jamila has been duped.

Trying to find out who stabbed Liam Glass is Detective Constable Andy Rackham. He is a walking tick-box of all the difficulties faced by an ambitious copper trying to please his bosses while being a supportive husband and father. The third member of this unholy trinity is Jamila Hasan, an earnest politician of Bengali origin who senses that the attack might be just the campaign platform she needs to ensure that she is re-elected. But what if Liam’s attackers are from her own community? Sadly, in her efforts to gain credibility on the street, Jamila has been duped.

Annemarie Neary gives us a chilling sense of separate events which are not fatal in themselves but deadly when they collide, and while Ro is making his way to Clapham, the normally self-assured Jess is in trouble at work. She has rejected the advances of a senior partner at an office social, and he uses the rebuff to light a fire under Jess’s professional life.

Annemarie Neary gives us a chilling sense of separate events which are not fatal in themselves but deadly when they collide, and while Ro is making his way to Clapham, the normally self-assured Jess is in trouble at work. She has rejected the advances of a senior partner at an office social, and he uses the rebuff to light a fire under Jess’s professional life.