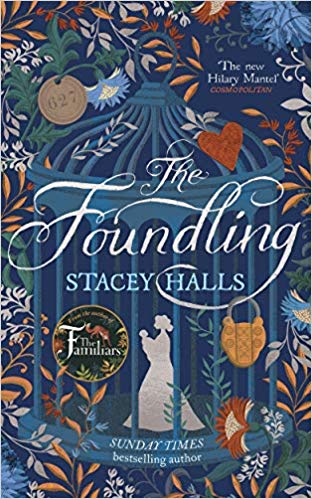

eing a middle class British father and grandfather, the concept of abandoning a newly born baby is totally beyond my experience of life and (the fault is perhaps mine) my comprehension. The fact is, however, that since Adam had his way with Eve, biology has trumped human intention, and babies have come into the world unloved and unwanted. Thankfully, there have been charitable institutions over the centuries which have done their best to provide some kind of home for foundlings. Abandoning babies is not something consigned to history: modern Germany has its Babyklappe, and Russia its Колыбель надежды – literally hatches – rather like an old fashioned bank deposit box – built into buildings where babies can be left. Back in time, Paris had its Maison de la Couche pour les Enfants Trouvés while in Florence the Ospedale degli Innocenti is one of the gems of early Renaissance architecture. London had its Foundling Hospital, and it is the centre of The Foundling, the new novel by Stacey Halls.

eing a middle class British father and grandfather, the concept of abandoning a newly born baby is totally beyond my experience of life and (the fault is perhaps mine) my comprehension. The fact is, however, that since Adam had his way with Eve, biology has trumped human intention, and babies have come into the world unloved and unwanted. Thankfully, there have been charitable institutions over the centuries which have done their best to provide some kind of home for foundlings. Abandoning babies is not something consigned to history: modern Germany has its Babyklappe, and Russia its Колыбель надежды – literally hatches – rather like an old fashioned bank deposit box – built into buildings where babies can be left. Back in time, Paris had its Maison de la Couche pour les Enfants Trouvés while in Florence the Ospedale degli Innocenti is one of the gems of early Renaissance architecture. London had its Foundling Hospital, and it is the centre of The Foundling, the new novel by Stacey Halls.

Bess Bright is a Shrimp Girl. Her father gets up at the crack of dawn to buy Essex shrimps from Billingsgate Market, and Bess puts the seafood in the brim of a broad hat and, clutching a tiny tankard to measure them out, she walks the streets of 1750s London selling her wares. For American readers it is worth explaining that British shrimps are tiny crustaceans, not ‘shrimp’, the larger creature we call ‘prawns’. In my opinion, the British shrimp is fiddly to prepare but spectacularly more tasty than its larger cousin.

Bess Bright is a Shrimp Girl. Her father gets up at the crack of dawn to buy Essex shrimps from Billingsgate Market, and Bess puts the seafood in the brim of a broad hat and, clutching a tiny tankard to measure them out, she walks the streets of 1750s London selling her wares. For American readers it is worth explaining that British shrimps are tiny crustaceans, not ‘shrimp’, the larger creature we call ‘prawns’. In my opinion, the British shrimp is fiddly to prepare but spectacularly more tasty than its larger cousin.

Bess has, to put it politely, ‘an encounter’ in a dingy back street, with an attractive young merchant who deals in whalebone – the staple component of 18th century corsets and also a carvable alternative to the more expensive tusks of elephants. Bess’s moment of passion has an almost inevitable consequence, and in the dingy rooms she rents with her father and brother, she gives birth to a healthy baby girl. During her pregnancy, however, Daniel Callard has died, thus ruling out any possible confrontation where Bess presents the child to its father, and says, “Your daughter, Sir!”

elling shrimps from the brim of your hat is not an occupation destined to provide sufficient funds to keep a growing child, and so Bess presents herself and baby Clara at The Foundling Hospital, London’s only repository for unwanted children. The Hospital does, however, offer hope to young mothers. Each child’s admittance is scrupulously recorded, and the mothers are asked to leave a small token – perhaps a square of fabric or another physical memento which – when circumstances permit – mothers can use to prove identity when they are able to return and claim their children.

elling shrimps from the brim of your hat is not an occupation destined to provide sufficient funds to keep a growing child, and so Bess presents herself and baby Clara at The Foundling Hospital, London’s only repository for unwanted children. The Hospital does, however, offer hope to young mothers. Each child’s admittance is scrupulously recorded, and the mothers are asked to leave a small token – perhaps a square of fabric or another physical memento which – when circumstances permit – mothers can use to prove identity when they are able to return and claim their children.

Bess works and works and works; her meagre profits are salted away until, some six years later, she returns to the Hospital with the funds to pay them back and collect Clara. Her mild anxiety at the prospect of being reunited with her daughter turns to horror when she is told that the baby was reclaimed, the day after she was admitted, when a woman calling herself Bess Bright arrived and showed the requisite token – the matching half of a divided heart, fashioned from whalebone.

ow – and where – Bess finds her missing daughter is for you to discover, but I promise that The Foundling is ingenious, delightful, and the author’s skills as a storyteller are magnetic. The attention to detail and the period authenticity are things to be wondered at, but what elevates this novel above the humdrum is how Stacey Halls conjures up our sheer emotional investment in the characters, each one beautifully observed. Art lovers will recognise the painter – and the title – of the picture below and, were he alive to read it, the great observer of London life would thoroughly approve of The Foundling, which is published by Manilla Press and is out on 3rd February in Kindle and 6th February in hardback

ow – and where – Bess finds her missing daughter is for you to discover, but I promise that The Foundling is ingenious, delightful, and the author’s skills as a storyteller are magnetic. The attention to detail and the period authenticity are things to be wondered at, but what elevates this novel above the humdrum is how Stacey Halls conjures up our sheer emotional investment in the characters, each one beautifully observed. Art lovers will recognise the painter – and the title – of the picture below and, were he alive to read it, the great observer of London life would thoroughly approve of The Foundling, which is published by Manilla Press and is out on 3rd February in Kindle and 6th February in hardback

or newcomers to the sublime world of Arthur Bryant and John May, the new collection of short stories written by their biographer, Christopher Fowler, contains a handy pull-out-and-keep guide to the personnel doings of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit. OK, I lie – don’t try and pull it out because it will wreck a beautiful book, but the other bits are true.

or newcomers to the sublime world of Arthur Bryant and John May, the new collection of short stories written by their biographer, Christopher Fowler, contains a handy pull-out-and-keep guide to the personnel doings of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit. OK, I lie – don’t try and pull it out because it will wreck a beautiful book, but the other bits are true. Leaving aside the pen pictures, introductions and postscripts, there are twelve stories. They are, for the most part, enjoyably formulaic in a Sherlockian way in that something inexplicable happens, May furrows his brow and Arthur comes up with a dazzling solution. Think of a dozen elegant variations of The Red Headed League, but with one or two being much darker in tone. Bryant & May and the Antichrist, for example, is a sombre tale of an elderly woman driven to suicide by the greed of a religious charlatan, while Bryant & May and the Invisible Woman reflects on the devastating effects of clinical depression. The stories are, of course set in London, apart from the delightfully improbable one where Arthur and John solve a murder within the blood-soaked walls of Bran Castle, once the des-res of Vlad Dracul III. Bryant & May and the Consul’s Son revisits Fowler’s fascination with the lost rivers of London, while Janice Longbright and the Best of Friends lets the redoubtable Ms L take centre stage.

Leaving aside the pen pictures, introductions and postscripts, there are twelve stories. They are, for the most part, enjoyably formulaic in a Sherlockian way in that something inexplicable happens, May furrows his brow and Arthur comes up with a dazzling solution. Think of a dozen elegant variations of The Red Headed League, but with one or two being much darker in tone. Bryant & May and the Antichrist, for example, is a sombre tale of an elderly woman driven to suicide by the greed of a religious charlatan, while Bryant & May and the Invisible Woman reflects on the devastating effects of clinical depression. The stories are, of course set in London, apart from the delightfully improbable one where Arthur and John solve a murder within the blood-soaked walls of Bran Castle, once the des-res of Vlad Dracul III. Bryant & May and the Consul’s Son revisits Fowler’s fascination with the lost rivers of London, while Janice Longbright and the Best of Friends lets the redoubtable Ms L take centre stage. he gags are as good as ever. While investigating a crime in a tattoo parlour, Arthur is mistaken for a customer and asked if he has a design in mind:

he gags are as good as ever. While investigating a crime in a tattoo parlour, Arthur is mistaken for a customer and asked if he has a design in mind: don’t know Christopher Fowler personally, but I infer from his social media presence that he is a thoroughly modern and cosmopolitan chap and, with his spending his time between homes in Barcelona and King’s Cross, he could never be described as a Little Englander. How wonderful, then, that he is the most quintessentially English writer of our time. His Bryant & May stories draw in magical threads from English culture. There is the humour, which recalls George and Weedon Grossmith, WS Gilbert, and the various ‘Beachcombers’ down the years, particularly DB Wyndham Lewis and JB Morton. Fowler’s eagle eye for the evocative power of mundane domestic ephemera mirrors that of John Betjeman, while his fascination with the magnetic pull of the layers of history beneath London’s streets channels Peter Ackroyd and Iain Sinclair.

don’t know Christopher Fowler personally, but I infer from his social media presence that he is a thoroughly modern and cosmopolitan chap and, with his spending his time between homes in Barcelona and King’s Cross, he could never be described as a Little Englander. How wonderful, then, that he is the most quintessentially English writer of our time. His Bryant & May stories draw in magical threads from English culture. There is the humour, which recalls George and Weedon Grossmith, WS Gilbert, and the various ‘Beachcombers’ down the years, particularly DB Wyndham Lewis and JB Morton. Fowler’s eagle eye for the evocative power of mundane domestic ephemera mirrors that of John Betjeman, while his fascination with the magnetic pull of the layers of history beneath London’s streets channels Peter Ackroyd and Iain Sinclair.

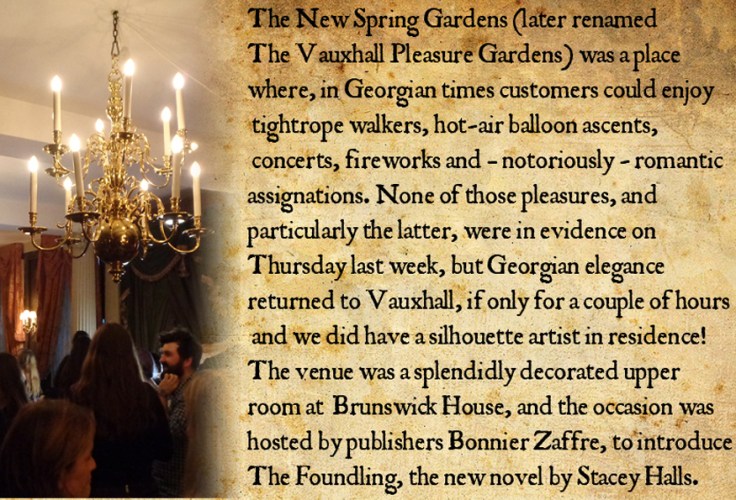

fter her success with

fter her success with  Zosha Nash (left), formerly Head of Development at The Foundling Museum explained, the care and love bestowed on the children was remarkable, even by modern standards. Their life expectancy exceeded that of many children at the time, and all were taught to read and write. The hospital was also famously associated with Handel, and it was in the chapel that Messiah was performed for the first time in England

Zosha Nash (left), formerly Head of Development at The Foundling Museum explained, the care and love bestowed on the children was remarkable, even by modern standards. Their life expectancy exceeded that of many children at the time, and all were taught to read and write. The hospital was also famously associated with Handel, and it was in the chapel that Messiah was performed for the first time in England

ix years after leaving her, Bess Bright returns to claim her daughter, to be greeting with the shattering news that Clara is no longer there. She has been claimed – just a day after Bess left her – by a woman correctly identifying the child’s token, a piece of scrimshaw, half a heart engraved with letters. The authorities are baffled, but convinced that a major fraud has been perpetrated. Bess’s shock turns to a passionate determination to find Clara.

ix years after leaving her, Bess Bright returns to claim her daughter, to be greeting with the shattering news that Clara is no longer there. She has been claimed – just a day after Bess left her – by a woman correctly identifying the child’s token, a piece of scrimshaw, half a heart engraved with letters. The authorities are baffled, but convinced that a major fraud has been perpetrated. Bess’s shock turns to a passionate determination to find Clara.

very so often a book comes along that is so beautifully written and so haunting that a reviewer has to dig deep to even begin to do it justice. Shamus Dust by Janet Roger is one such. The author seems, as they say, to have come from nowhere. No previous books. No hobnobbing on social media. So who is Janet Roger? On her website she says:

very so often a book comes along that is so beautifully written and so haunting that a reviewer has to dig deep to even begin to do it justice. Shamus Dust by Janet Roger is one such. The author seems, as they say, to have come from nowhere. No previous books. No hobnobbing on social media. So who is Janet Roger? On her website she says:

ig mistake. Councillor Drake underestimates Newman’s intelligence and natural scepticism. Our man uncovers a homosexual vice ring, a cabal of opportunists who stand to make millions by rebuilding a shattered city, and an archaeological discovery which could halt their reconstruction bonanza.

ig mistake. Councillor Drake underestimates Newman’s intelligence and natural scepticism. Our man uncovers a homosexual vice ring, a cabal of opportunists who stand to make millions by rebuilding a shattered city, and an archaeological discovery which could halt their reconstruction bonanza.

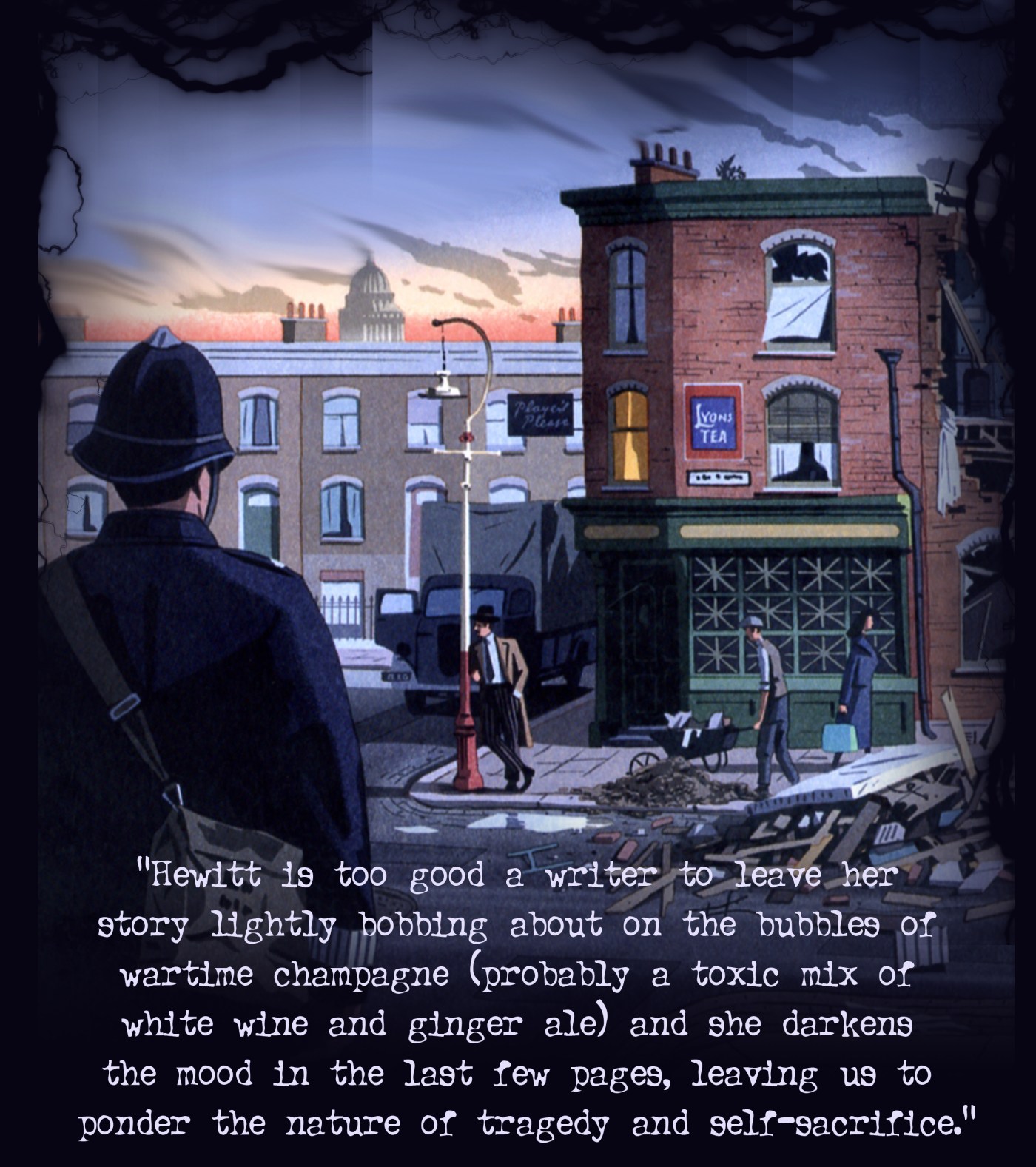

his 1943 novel by Kathleen Hewitt is the third in the excellent series of Imperial War Museum reprints of wartime classics, but couldn’t be more different from the first two,

his 1943 novel by Kathleen Hewitt is the third in the excellent series of Imperial War Museum reprints of wartime classics, but couldn’t be more different from the first two,  A jolly murder? Well, of course. Fictional murders can be range from brutal to comic depending on the genre, and although the corpse found in the back garden of Mrs Meake’s lodging house – 15 Terrapin Road – is just as dead as any described by Val McDermid or Michael Connelly, the mood is set by the chief amateur investigator, a breezy and frightfully English RAF pilot called David Heron on recuperation leave from his squadron, and his elegantly witty lady friend Tess. He is from solid county stock:

A jolly murder? Well, of course. Fictional murders can be range from brutal to comic depending on the genre, and although the corpse found in the back garden of Mrs Meake’s lodging house – 15 Terrapin Road – is just as dead as any described by Val McDermid or Michael Connelly, the mood is set by the chief amateur investigator, a breezy and frightfully English RAF pilot called David Heron on recuperation leave from his squadron, and his elegantly witty lady friend Tess. He is from solid county stock: eaders will not need a degree in 20th century social history to recognise that the book’s title refers to the methods used by shopkeepers to circumvent the official rationing of food and fancy goods. More sinister is the presence – both in real life and in the book – of criminals who exploit the shortages to make serious money playing the black market and for whom deadly violence is just a way of life.

eaders will not need a degree in 20th century social history to recognise that the book’s title refers to the methods used by shopkeepers to circumvent the official rationing of food and fancy goods. More sinister is the presence – both in real life and in the book – of criminals who exploit the shortages to make serious money playing the black market and for whom deadly violence is just a way of life.

The story rattles along in fine style as the hours tick by before David has to return to the war. He has two pressing needs. One is to buy the special licence which will enable him to marry Tess, and the other is to find the Terrapin Road murderer. Hewitt (right) is too good a writer to leave her story lightly bobbing about on the bubbles of wartime champagne (probably a toxic mix of white wine and ginger ale) and she darkens the mood in the last few pages, leaving us to ponder the nature of tragedy and self-sacrifice.

The story rattles along in fine style as the hours tick by before David has to return to the war. He has two pressing needs. One is to buy the special licence which will enable him to marry Tess, and the other is to find the Terrapin Road murderer. Hewitt (right) is too good a writer to leave her story lightly bobbing about on the bubbles of wartime champagne (probably a toxic mix of white wine and ginger ale) and she darkens the mood in the last few pages, leaving us to ponder the nature of tragedy and self-sacrifice.

We first met London’s Detective Inspector Jake Porter and Sergeant Nick Styles in Robert Scragg’s debut novel What Falls Between The Cracks (

We first met London’s Detective Inspector Jake Porter and Sergeant Nick Styles in Robert Scragg’s debut novel What Falls Between The Cracks (

orter is still haunted by the death of his wife in a hit-and-run accident and, like all good fictional DIs, he is viewed by his bosses – in particular the officious desk jockey Milburn – as mentally suspect. He is forced to go for a series of counselling sessions with the force’s tame psychologist, but after one hurried and fruitless encounter, he becomes totally immersed in a puzzling case which involves an old friend of his, Max Brennan. Brennan has arranged to meet his long-estranged father for the first time, but the older man fails to make the rendezvous. When Brennan’s girlfriend is abducted, he turns to Porter for help.

orter is still haunted by the death of his wife in a hit-and-run accident and, like all good fictional DIs, he is viewed by his bosses – in particular the officious desk jockey Milburn – as mentally suspect. He is forced to go for a series of counselling sessions with the force’s tame psychologist, but after one hurried and fruitless encounter, he becomes totally immersed in a puzzling case which involves an old friend of his, Max Brennan. Brennan has arranged to meet his long-estranged father for the first time, but the older man fails to make the rendezvous. When Brennan’s girlfriend is abducted, he turns to Porter for help. eanwhile, Styles has a secret. His wife is expecting their first child and she has grave misgivings about her husband continuing as Porter’s partner, as their business puts them all too often – and quite literally – in the line of fire. Understandably, she recoils at the possibility of raising the child alone with the painful duty, at some point, of explaining to the toddler about the father they never knew. Styles has accepted her demand to transfer to something less dangerous, but as the Brennan Affair ratchets up in intensity, he just can’t seem to find the right moment to break the news to his boss.

eanwhile, Styles has a secret. His wife is expecting their first child and she has grave misgivings about her husband continuing as Porter’s partner, as their business puts them all too often – and quite literally – in the line of fire. Understandably, she recoils at the possibility of raising the child alone with the painful duty, at some point, of explaining to the toddler about the father they never knew. Styles has accepted her demand to transfer to something less dangerous, but as the Brennan Affair ratchets up in intensity, he just can’t seem to find the right moment to break the news to his boss.

London. 1894. The British Museum has become a crime scene. A distinguished academic and author has been brutally stabbed to death. Not in the hushed corridors, not in the dusty silence of The Reading Room, and not even in one of the stately exhibition halls, under the stony gaze of Assyrian gods and Greek athletes. No, Professor Lance Pickering has been found in the distinctly less grand cubicle of one of the museum’s … ahem …. conveniences, the door locked from inside, and the unfortunate professor slumped over the porcelain.

London. 1894. The British Museum has become a crime scene. A distinguished academic and author has been brutally stabbed to death. Not in the hushed corridors, not in the dusty silence of The Reading Room, and not even in one of the stately exhibition halls, under the stony gaze of Assyrian gods and Greek athletes. No, Professor Lance Pickering has been found in the distinctly less grand cubicle of one of the museum’s … ahem …. conveniences, the door locked from inside, and the unfortunate professor slumped over the porcelain.

This is a highly readable mystery with two engaging central characters, a convincing late Victorian London setting, and a plot which takes us this way and that before Daniel and Abigail uncover the tragic truth behind the murders. Jim Eldridge (right) is a veteran writer for radio, television and film as well as being the author of historical fiction, children’s novels and educational books. Murder At The British Museum is published by Allison & Busby,

This is a highly readable mystery with two engaging central characters, a convincing late Victorian London setting, and a plot which takes us this way and that before Daniel and Abigail uncover the tragic truth behind the murders. Jim Eldridge (right) is a veteran writer for radio, television and film as well as being the author of historical fiction, children’s novels and educational books. Murder At The British Museum is published by Allison & Busby,

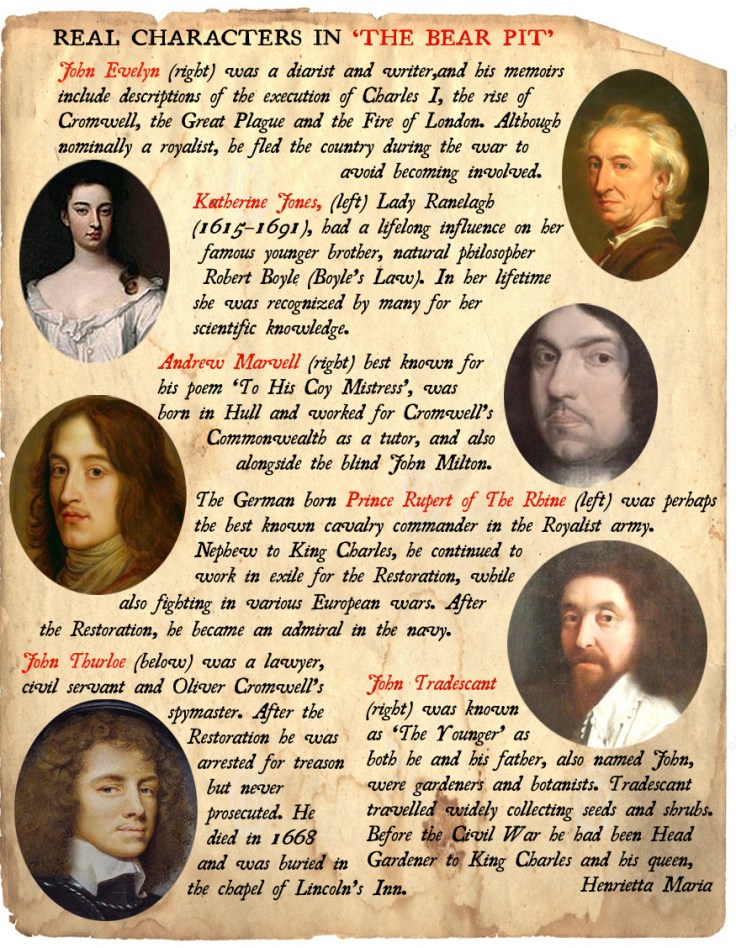

In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector.

In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector. hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history

hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history  tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

t takes a very ingenious – not to say devious mind – to fashion a fiction plot which meshes together a whole bagful of disparate elements to make a satisfying whole that challenges the imagination but does not exceed it in possibility. Adam Loxley has done just that in his latest thriller The Artemis File. George Wiggins is Mr Ordinary. He lives in what would have been called, years ago, a bijou residence in the twee Kentish town of Tenterden. He is not Mr Stupid, however. He travels into ‘town’ each day to sit at his desk in Fleet Street where he composes the daily crossword for The Chronicle under his pseudonym Xerxes. Aficionados know that in reality, all that is left of the newspaper industry in Fleet Street are the buildings, and the use of the term to denote popular journalism, but we can forgive Loxley for having the good, old-fashioned Chronicle hanging on by the skin of its teeth when all its fellows have decamped to Wapping or soulless suburbs somewhere off a dual carriageway.

t takes a very ingenious – not to say devious mind – to fashion a fiction plot which meshes together a whole bagful of disparate elements to make a satisfying whole that challenges the imagination but does not exceed it in possibility. Adam Loxley has done just that in his latest thriller The Artemis File. George Wiggins is Mr Ordinary. He lives in what would have been called, years ago, a bijou residence in the twee Kentish town of Tenterden. He is not Mr Stupid, however. He travels into ‘town’ each day to sit at his desk in Fleet Street where he composes the daily crossword for The Chronicle under his pseudonym Xerxes. Aficionados know that in reality, all that is left of the newspaper industry in Fleet Street are the buildings, and the use of the term to denote popular journalism, but we can forgive Loxley for having the good, old-fashioned Chronicle hanging on by the skin of its teeth when all its fellows have decamped to Wapping or soulless suburbs somewhere off a dual carriageway. When George has a rather startling experience in his local pub after a couple of pints of decent beer, the other elements of the story – MI5, the CIA, Russian agents, immaculately dressed but ruthless Whitehall civil servants and, most crucially, the most infamous unsolved incident of the late 20th century – are soon thrown into the mix. Such is George’s conformity, it is easily compromised, and he is blackmailed into writing a crossword, the answers to which are deeply significant to a very select group of individuals who sit at the centres of various spiders’ webs where they tug the strands which control the national security of the great powers.

When George has a rather startling experience in his local pub after a couple of pints of decent beer, the other elements of the story – MI5, the CIA, Russian agents, immaculately dressed but ruthless Whitehall civil servants and, most crucially, the most infamous unsolved incident of the late 20th century – are soon thrown into the mix. Such is George’s conformity, it is easily compromised, and he is blackmailed into writing a crossword, the answers to which are deeply significant to a very select group of individuals who sit at the centres of various spiders’ webs where they tug the strands which control the national security of the great powers. eorge Wiggins might have been easily duped and he has few means to fight back, but he recruits an old chum from the Chronicle whose knowledge of the historical events of the 1990s proves key to unraveling the mystery of who wanted the crossword published – and why. While the pair rescue a dusty file from an obscure repository and pore over its contents, elsewhere a much more visceral struggle is playing out. A ruthless MI5 contract ‘fixer’ called Craven is engaged on a courtly dance of death with a former CIA agent, current American operatives and their Russian counterparts.

eorge Wiggins might have been easily duped and he has few means to fight back, but he recruits an old chum from the Chronicle whose knowledge of the historical events of the 1990s proves key to unraveling the mystery of who wanted the crossword published – and why. While the pair rescue a dusty file from an obscure repository and pore over its contents, elsewhere a much more visceral struggle is playing out. A ruthless MI5 contract ‘fixer’ called Craven is engaged on a courtly dance of death with a former CIA agent, current American operatives and their Russian counterparts.