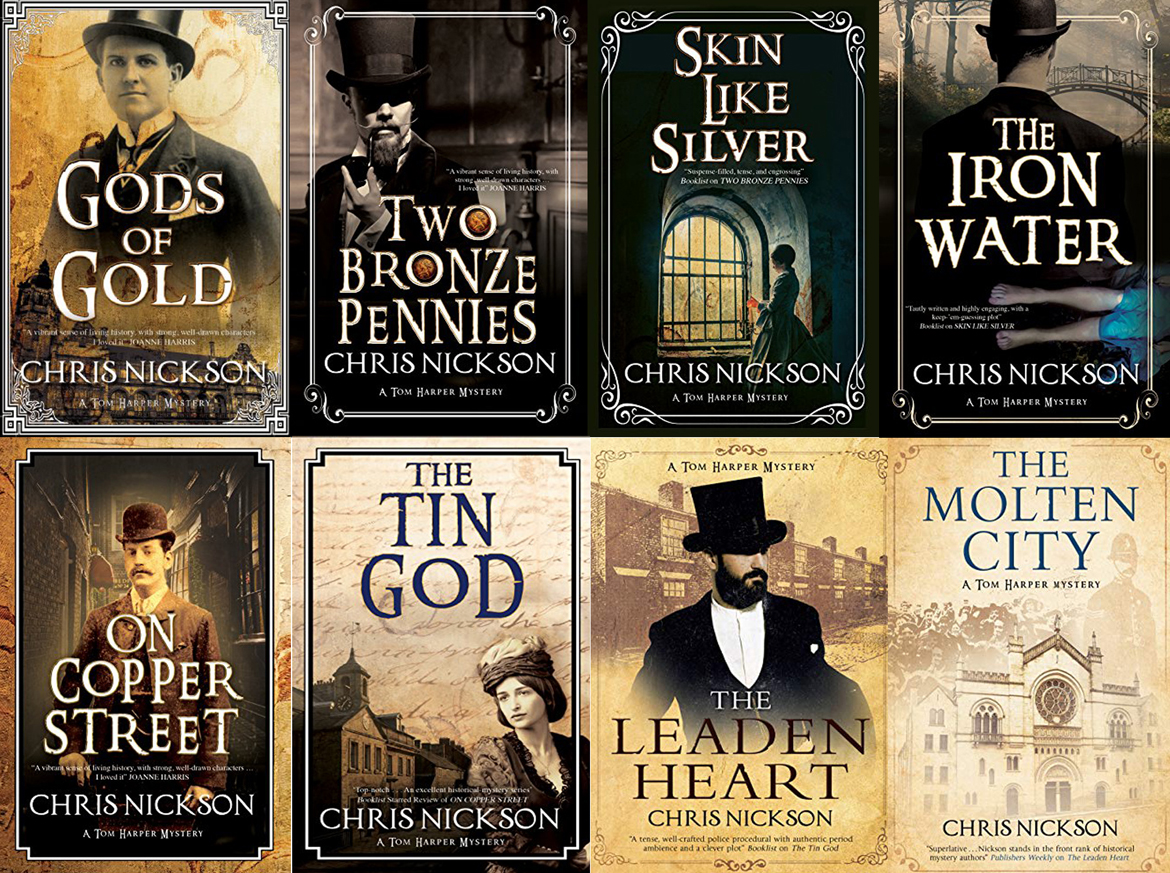

The prolific and ever-reliable Yorkshire author Chris Nickson has been writing his Tom Harper series since 2014 when he introduced the Leeds copper in Gods of Gold. Since then he has stuck to the theme of metal in the book titles, and now we have Brass Lives. Harper is now Deputy Chief Constable of the city where we first met him as a young detective in the 1890s.

As is customary, the action doesn’t stray much beyond the city and its surrounding (and rapidly diminishing) countryside, but a slightly exotic element is introduced by way of two American gangsters. One, Davey Mullen, was born in Leeds, but emigrated across the Atlantic, where he has found infamy and wealth as a New York gangster. He has returned to his home town to visit his father. Louis Herman Fess, on the other hand has no interest in Leeds other than the fact that it is the current whereabouts of Mullen. Fess is a member of the delightfully named Hudson Dusters gang. They shot rival hoodlum Mullen eleven times, but he survived, and it seems as if Fess has come to West Yorkshire to resolve unfinished business. When Fess is found shot dead, Mullen is the obvious suspect, but try as they may, Harper and his team can find no evidence to link Mullen to the killing.

Politics are never far away in Chris NIckson novels, and in this case it is the enthusiasm of his delightful wife, Annabelle, for the Suffragist cause that takes centre stage. Note the word ‘Suffragist’ rather than ‘Suffragette’, a term we are more familiar with. The Suffragists were the earliest group to seek emancipation and electoral parity, and they believed in the power of persuasion, debate and education, rather than the direct action for which the Suffragettes were later known. Annabelle has always been careful not to embarrass her husband by falling foul of the law, but she plans to march alongside other campaigners in a march which is shortly due to enter Leeds. (See footnote * for more details) Annabelle’s plans are, however, thwarted at the last moment by a cruel twist of fate.

Politics are never far away in Chris NIckson novels, and in this case it is the enthusiasm of his delightful wife, Annabelle, for the Suffragist cause that takes centre stage. Note the word ‘Suffragist’ rather than ‘Suffragette’, a term we are more familiar with. The Suffragists were the earliest group to seek emancipation and electoral parity, and they believed in the power of persuasion, debate and education, rather than the direct action for which the Suffragettes were later known. Annabelle has always been careful not to embarrass her husband by falling foul of the law, but she plans to march alongside other campaigners in a march which is shortly due to enter Leeds. (See footnote * for more details) Annabelle’s plans are, however, thwarted at the last moment by a cruel twist of fate.

There is more murder and mayhem on the streets of Leeds and Tom Harper finds himself battling to solve perhaps the most complex case of his career, made all the more intractable because he faces a personal challenge more daunting than any he has ever faced in his professional life. Guns have played little part in Harper’s police career thus far, but the theft of four Webley revolvers – plus ammunition – from Harewood Barracks, and the subsequent purchase of the guns by members of the Leeds underworld, adds a new and dangerous dimension to the case.

Nickson’s love for his city – with all its many blemishes – is often voiced in the thoughts of Tom Harper. Here, he declines the use of his chauffeur driven car and opts for Shanks’s Pony:

“A good walk to Sheepscar. A chance to idle along, to see things up close rather than hidden away in a motor car where he passed so quickly. All the smells and sounds that made up Leeds. Kosher food cooking in the Leylands, sauerkraut and chicken and the constant hum of sewing machines in the sweatshops. The malt from Brunswick brewery. The hot stink of iron rising from the foundries and the sewage stink of chemical works and tanneries up Meanwood Road. Little of it was lovely. But all of it was his. It was home.”

Harper, rather like WS Gilbert’s Ko-Ko, has a little list. It contains all the victims – and possible perpetrators – of the spate of crimes connected to Davey Mullen. One by one, through a mixture of persistence, skill and good luck, he manages to put a line through most of them by the closing chapters of Brass Lives. The book ends, however, on a sombre note, rather like a funeral bell tolling: it warns of a future that will have devastating consequences not only for Tom Harper, his family and his colleagues, but for millions of people right across Europe.

I believe that this series will be seen by readers, some of whom are still learning to read, as a perfect sequence that epitomises the very best of historical crime fiction. The empathy, the attention to detail, and the raw truth of how our ancestors lived will make the Tom Harper novels timeless. Brass Lives is published by Severn House in hardback, and is available now. It will be out as a Kindle in August. For reviews of other novels in this excellent series, click on the graphic below.

*The Great Pilgrimage of 1913 was a march in Britain by suffragists campaigning non-violently for women’s suffrage, organised by the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Women marched to London from all around England and Wales and 50,000 attended a rally in Hyde Park.

This shouldn’t be dismissed as ‘comfort reading’. Yes, we know what we are going to get – the atmospheric late Victorian setting, the warm human chemistry between Daniel and Abigail, the absence of moral ambiguity and the certainty that good will prevail. Any genuine reader of fiction – and in particular, crime fiction – will know that, rather in the manner of Ecclesiastes chapter III , there is a time for everything; there is a time for the dark despair of Derek Raymond, there is a time for the intense psychological dramas of Lisa Jewell, and a time for workaday police procedurals by writers like Peter James and Mark Billingham. There is also a time for superbly crafted historical crime fiction which takes us far away in time and space, and allows us to escape into an – albeit imaginary – world which provides balm and healing to our present woes. Murder at Madame Tussaud’s is one such book. It is published by Allison & Busby and is

This shouldn’t be dismissed as ‘comfort reading’. Yes, we know what we are going to get – the atmospheric late Victorian setting, the warm human chemistry between Daniel and Abigail, the absence of moral ambiguity and the certainty that good will prevail. Any genuine reader of fiction – and in particular, crime fiction – will know that, rather in the manner of Ecclesiastes chapter III , there is a time for everything; there is a time for the dark despair of Derek Raymond, there is a time for the intense psychological dramas of Lisa Jewell, and a time for workaday police procedurals by writers like Peter James and Mark Billingham. There is also a time for superbly crafted historical crime fiction which takes us far away in time and space, and allows us to escape into an – albeit imaginary – world which provides balm and healing to our present woes. Murder at Madame Tussaud’s is one such book. It is published by Allison & Busby and is

Russell is a survivor, a man who can usually talk his way out of trouble. Multilingual, and with that all-important American passport, he keeps a wary eye on the features he wires back to his newspaper in the states, but has – more or less – managed to stay out of trouble with the various arms of the Nazi state – principally the Gestapo, the SS and their nasty little brother the Sicherheitsdienst. Russell fought in the British Army in The Great War, but in its wake became a committed Communist. Although he has now ‘left the faith’ he still maintains discreet contacts with the remaining ‘comrades’ in Berlin. With that in mind, it is unsurprising, perhaps, that he has been manoeuvred into the sticky position where both the German and Russian intelligence services believe that he is working uniquely for them, and he is being used to pass on false information from one to the other.

Russell is a survivor, a man who can usually talk his way out of trouble. Multilingual, and with that all-important American passport, he keeps a wary eye on the features he wires back to his newspaper in the states, but has – more or less – managed to stay out of trouble with the various arms of the Nazi state – principally the Gestapo, the SS and their nasty little brother the Sicherheitsdienst. Russell fought in the British Army in The Great War, but in its wake became a committed Communist. Although he has now ‘left the faith’ he still maintains discreet contacts with the remaining ‘comrades’ in Berlin. With that in mind, it is unsurprising, perhaps, that he has been manoeuvred into the sticky position where both the German and Russian intelligence services believe that he is working uniquely for them, and he is being used to pass on false information from one to the other.

While reporting on the death and mutilation of a young rent boy, Russell is asked by a friend to take on another case, this time on behalf of a senior army officer whose daughter is missing. It is a delicate business, because there is a strong suspicion that Lili Zollitsch has run off with a boyfriend who is an active member of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands.

While reporting on the death and mutilation of a young rent boy, Russell is asked by a friend to take on another case, this time on behalf of a senior army officer whose daughter is missing. It is a delicate business, because there is a strong suspicion that Lili Zollitsch has run off with a boyfriend who is an active member of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands.

When a rent boy is found dead, his throat cut from ear to ear, there is initially little interest by the police, as the lad is just assumed to have paid the price for being in a risky line of business, but when the post mortem reveals that he has had every drop of blood drained from his body, Quinn is summoned and told to investigate. After a droll episode where Quinn decides to pose as a man smitten by “the love that dare not speak its name”, and blunders around in a dodgy bookshop, but he does find out that the dead youngster was called Jimmy, and had links to a ‘gentleman’s club’ where he would find men appreciative of his talents.

When a rent boy is found dead, his throat cut from ear to ear, there is initially little interest by the police, as the lad is just assumed to have paid the price for being in a risky line of business, but when the post mortem reveals that he has had every drop of blood drained from his body, Quinn is summoned and told to investigate. After a droll episode where Quinn decides to pose as a man smitten by “the love that dare not speak its name”, and blunders around in a dodgy bookshop, but he does find out that the dead youngster was called Jimmy, and had links to a ‘gentleman’s club’ where he would find men appreciative of his talents.

Thankfully, Morris makes no attempt to get in the politics of homosexuality and the law: his characters simply inhabit the world in which he puts them, and their thoughts, words and deeds resonate authentically. In 1914, remember, the trial of Oscar Wilde and the Cleveland Street Scandal were still part of folk memory. It’s an astonishing thought that had Morris been writing about similar murders, fifty years later in 1964, virtually nothing would have changed – think of the scandals involving such ‘big names’ as Tom Driberg, Robert Boothby and Ronnie Kray, and how their lives have been written up by such novelists as Jake Arnott, John Lawton and James Barlow.

Thankfully, Morris makes no attempt to get in the politics of homosexuality and the law: his characters simply inhabit the world in which he puts them, and their thoughts, words and deeds resonate authentically. In 1914, remember, the trial of Oscar Wilde and the Cleveland Street Scandal were still part of folk memory. It’s an astonishing thought that had Morris been writing about similar murders, fifty years later in 1964, virtually nothing would have changed – think of the scandals involving such ‘big names’ as Tom Driberg, Robert Boothby and Ronnie Kray, and how their lives have been written up by such novelists as Jake Arnott, John Lawton and James Barlow.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot.

As ever, murder is the word, and a series of deaths in and around the town of Omskirk are linked to an archaic form of business plan for raising money, known as a Tontine. The investment plan was named after Neapolitan banker Lorenzo de Tonti and, to put it simply, was a pot of money where a number of people contributed an equal sum. The money would either be invested, with interest paid to the members, or used to fund capital projects. As time went on, and investors died, the fund became the property of the remaining members, until the last man (or woman) standing hit the jackpot. One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

One by one the Tontine signatories come to sticky ends: one is, apparently, hit by the sail of a windmill; another is found dead on Crosby beach, apparently drowned, but Luke Fidelis conducts a post mortem and finds that the dead man’s body has been dumped on the seashore. Things become even more complex when a reformed ‘lady of the night’, now a maid, is accused of pushing the poor woman into the path of the windmill sail. Cragg is convinced she is innocent, but faces an uphill struggle against a corrupt judge.

Mason is a man given to reflection, and a case from his early career still troubles him. On 30th September 1923, a boy’s body was found near the local church hall. Robert McFarlane had been missing for three days, his widowed mother frantic with anxiety. Mason remembers the corpse vividly. It was almost as if the lad was just sleeping. The cause of death? Totally improbably the boy drowned. But where? And why was his body so artfully posed, waiting to be found?

Mason is a man given to reflection, and a case from his early career still troubles him. On 30th September 1923, a boy’s body was found near the local church hall. Robert McFarlane had been missing for three days, his widowed mother frantic with anxiety. Mason remembers the corpse vividly. It was almost as if the lad was just sleeping. The cause of death? Totally improbably the boy drowned. But where? And why was his body so artfully posed, waiting to be found?