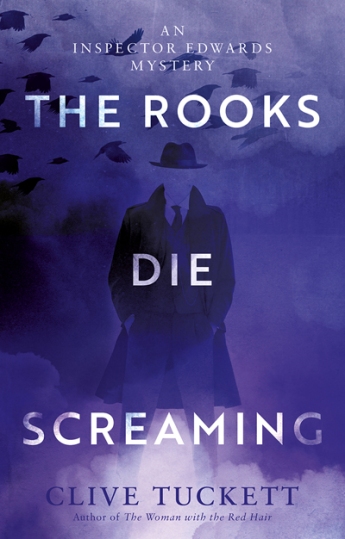

he dramatic events of The Rooks Die Screaming take place in the spring of 1921 in the Cornish market town of Bodmin. The bare bones of the story are that Detective Inspector Cyril Edwards of Scotland Yard has come to Bodmin to investigate murder and treachery involving a group of spies known as The Four Rooks. This book is a sequel to The Woman With The Red Hair, and to say there is a back-story is something of an understatement. The eponymous young woman is called Morag and, amongst other things, is Edwards’ sister-in-law. Elisha Edwards was one of the millions of unfortunates taken by an agent even deadlier than high explosives and machine gun bullets – Spanish Influenza.

he dramatic events of The Rooks Die Screaming take place in the spring of 1921 in the Cornish market town of Bodmin. The bare bones of the story are that Detective Inspector Cyril Edwards of Scotland Yard has come to Bodmin to investigate murder and treachery involving a group of spies known as The Four Rooks. This book is a sequel to The Woman With The Red Hair, and to say there is a back-story is something of an understatement. The eponymous young woman is called Morag and, amongst other things, is Edwards’ sister-in-law. Elisha Edwards was one of the millions of unfortunates taken by an agent even deadlier than high explosives and machine gun bullets – Spanish Influenza.

Morag is now Lady Frobisher. Her husband Harry, heir to The Fobisher Estate on the outskirts of Bodmin, is blind, victim of a grenade in the Flanders trenches. In the previous novel, Frobisher Hall was the scene of great torment for Morag, as she fell into the clutches of Morgan Treaves, an insane asylum keeper and his evil nurse. Treaves has disappeared after being disfigured with a broken bottle, wielded my Morag in a life or death struggle.

Morag is now Lady Frobisher. Her husband Harry, heir to The Fobisher Estate on the outskirts of Bodmin, is blind, victim of a grenade in the Flanders trenches. In the previous novel, Frobisher Hall was the scene of great torment for Morag, as she fell into the clutches of Morgan Treaves, an insane asylum keeper and his evil nurse. Treaves has disappeared after being disfigured with a broken bottle, wielded my Morag in a life or death struggle.

If you are picking up a sense that this novel has something of a Gothick tinge (note the ‘k’) you will not be far wrong. It is high melodrama for much of the way; secret tunnels; a sinister woman in the woods who, guarded by a lumbering giant mute forever silenced by the horrors he witnessed in the war, mixes deadly potions; a cottage where a sensitive soul can still hear the ghostly creaking of the former occupant’s body swinging from her suicide beam; a woman who, in falling prey to her own desires, has two terrible deaths forever on her conscience.

That said, The Rooks Die Screaming is inspired escapist reading. It would be unfair to say that Tuckett (right) writes in an anachronistic style. This is much, much better than pastiche, even though there are elements of Conan Doyle, the Golden Age, John Buchan and even touches of Sapper and MR James. So, eventually, to the plot, but we need to know a little more about Cyril Edwards. Like many a fictional detective inspector he is his own man. In another nice cultural reference Tuckett adds a touch of Charters and Caldicott as Edwards explains to the bumptious Standish, a mysterious officer from Military Intelligence;

That said, The Rooks Die Screaming is inspired escapist reading. It would be unfair to say that Tuckett (right) writes in an anachronistic style. This is much, much better than pastiche, even though there are elements of Conan Doyle, the Golden Age, John Buchan and even touches of Sapper and MR James. So, eventually, to the plot, but we need to know a little more about Cyril Edwards. Like many a fictional detective inspector he is his own man. In another nice cultural reference Tuckett adds a touch of Charters and Caldicott as Edwards explains to the bumptious Standish, a mysterious officer from Military Intelligence;

“‘I love cricket …. When I’m not turning down invitations to join dubious organisations, and thumping arrogant members of the royal family, I love nothing more than to relax at Lord’s and watch a game of cricket.’

Edwards stretched and picked up his Fedora hat, thinking of getting up and walking out of the room.

” I’m hoping to see the Second Test at Lord’s next month against Australia.”‘

tandish orders Edwards to investigate the possibility that Harry Frobisher is one of the Rooks, but one who has betrayed his country. Arriving in Bodmin his first task is to explain to the local police how a corpse found on a train is that of a notorious London contract killer. Tuckett’s Bodmin is full of stock characters, including a stolid police sergeant, an apparently tremulous clergyman and a punctilious but respected solicitor who is privy to all the secrets of the local gentry, but is oh, so discreet. To add to the fun, Frobisher Hall also has its requisite roll call of faithful retainers.

tandish orders Edwards to investigate the possibility that Harry Frobisher is one of the Rooks, but one who has betrayed his country. Arriving in Bodmin his first task is to explain to the local police how a corpse found on a train is that of a notorious London contract killer. Tuckett’s Bodmin is full of stock characters, including a stolid police sergeant, an apparently tremulous clergyman and a punctilious but respected solicitor who is privy to all the secrets of the local gentry, but is oh, so discreet. To add to the fun, Frobisher Hall also has its requisite roll call of faithful retainers.

The secret of The Four Rooks is eventually revealed, but not before the author throws a few red herrings onto the table. I could probably have done without the finer details of Lady Morag’s marriage bed, and some tighter proof-reading coupled with a more enticing cover would have done wonders for the book. That said, I enjoyed every page and I hope Clive Tuckett has another Inspector Edwards case up his sleeve, especially if it involves the redoubtable Morag Frobisher.

The Rooks Die Screaming is published by The Book Guild and is available now.

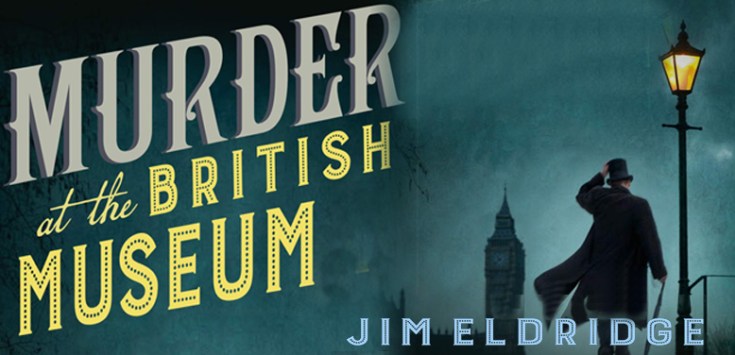

London. 1894. The British Museum has become a crime scene. A distinguished academic and author has been brutally stabbed to death. Not in the hushed corridors, not in the dusty silence of The Reading Room, and not even in one of the stately exhibition halls, under the stony gaze of Assyrian gods and Greek athletes. No, Professor Lance Pickering has been found in the distinctly less grand cubicle of one of the museum’s … ahem …. conveniences, the door locked from inside, and the unfortunate professor slumped over the porcelain.

London. 1894. The British Museum has become a crime scene. A distinguished academic and author has been brutally stabbed to death. Not in the hushed corridors, not in the dusty silence of The Reading Room, and not even in one of the stately exhibition halls, under the stony gaze of Assyrian gods and Greek athletes. No, Professor Lance Pickering has been found in the distinctly less grand cubicle of one of the museum’s … ahem …. conveniences, the door locked from inside, and the unfortunate professor slumped over the porcelain.

This is a highly readable mystery with two engaging central characters, a convincing late Victorian London setting, and a plot which takes us this way and that before Daniel and Abigail uncover the tragic truth behind the murders. Jim Eldridge (right) is a veteran writer for radio, television and film as well as being the author of historical fiction, children’s novels and educational books. Murder At The British Museum is published by Allison & Busby,

This is a highly readable mystery with two engaging central characters, a convincing late Victorian London setting, and a plot which takes us this way and that before Daniel and Abigail uncover the tragic truth behind the murders. Jim Eldridge (right) is a veteran writer for radio, television and film as well as being the author of historical fiction, children’s novels and educational books. Murder At The British Museum is published by Allison & Busby,

olitical disagreement in modern mainland Britain is largely non-violent, with the dishonorable exceptions of Islamic extremists and – further back – Irish Republican terror. For sure, tempers fray, abuse is hurled and fists are shaken. Just occasionally an egg, or maybe a milkshake, is thrown. You mightn’t think it, given the paroxysms of fury displayed on social media, but sticks and stones are rarely seen. Scottish writer SG MacLean in her series featuring the Cromwellian enforcer Damian Seeker reminds us that we have a violent history.

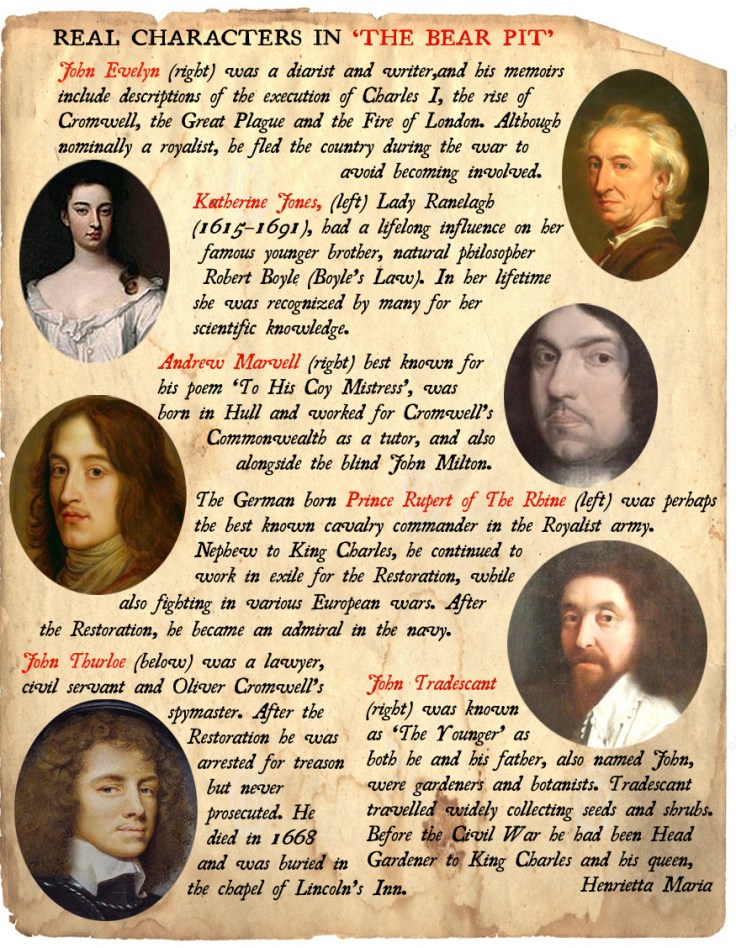

olitical disagreement in modern mainland Britain is largely non-violent, with the dishonorable exceptions of Islamic extremists and – further back – Irish Republican terror. For sure, tempers fray, abuse is hurled and fists are shaken. Just occasionally an egg, or maybe a milkshake, is thrown. You mightn’t think it, given the paroxysms of fury displayed on social media, but sticks and stones are rarely seen. Scottish writer SG MacLean in her series featuring the Cromwellian enforcer Damian Seeker reminds us that we have a violent history. In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector.

In the last of England’s civil wars, forces opposed to King Charles 1st and his belief in the divine right of kings have won the day. 1656. Charles has been dead these seven years and his son, another Charles, has escaped by the skin of his teeth after an abortive military campaign in 1651. He has been given sanctuary ‘across the water’, but his agents still believe they can stir up the population against his father’s nemesis – Oliver Cromwell, The Lord Protector. hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history

hile Seeker searches for his bear, he has another major task on his hands. A group of what we now call terrorists is in London, and they mean to cut off the very head of what they view as England’s Hydra by assassinating Oliver Cromwell himself. Rather like Clint Eastwood in In The Line of Fire and Kevin Costner in The Bodyguard, Seeker has one job, and that is to ensure that the No.1 client remains secure. Of course, history  tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

tells us that Seeker succeeds, but along the way SG MacLean (right) makes sure we have a bumpy ride through the mixture of squalor and magnificence that is 17th century London.

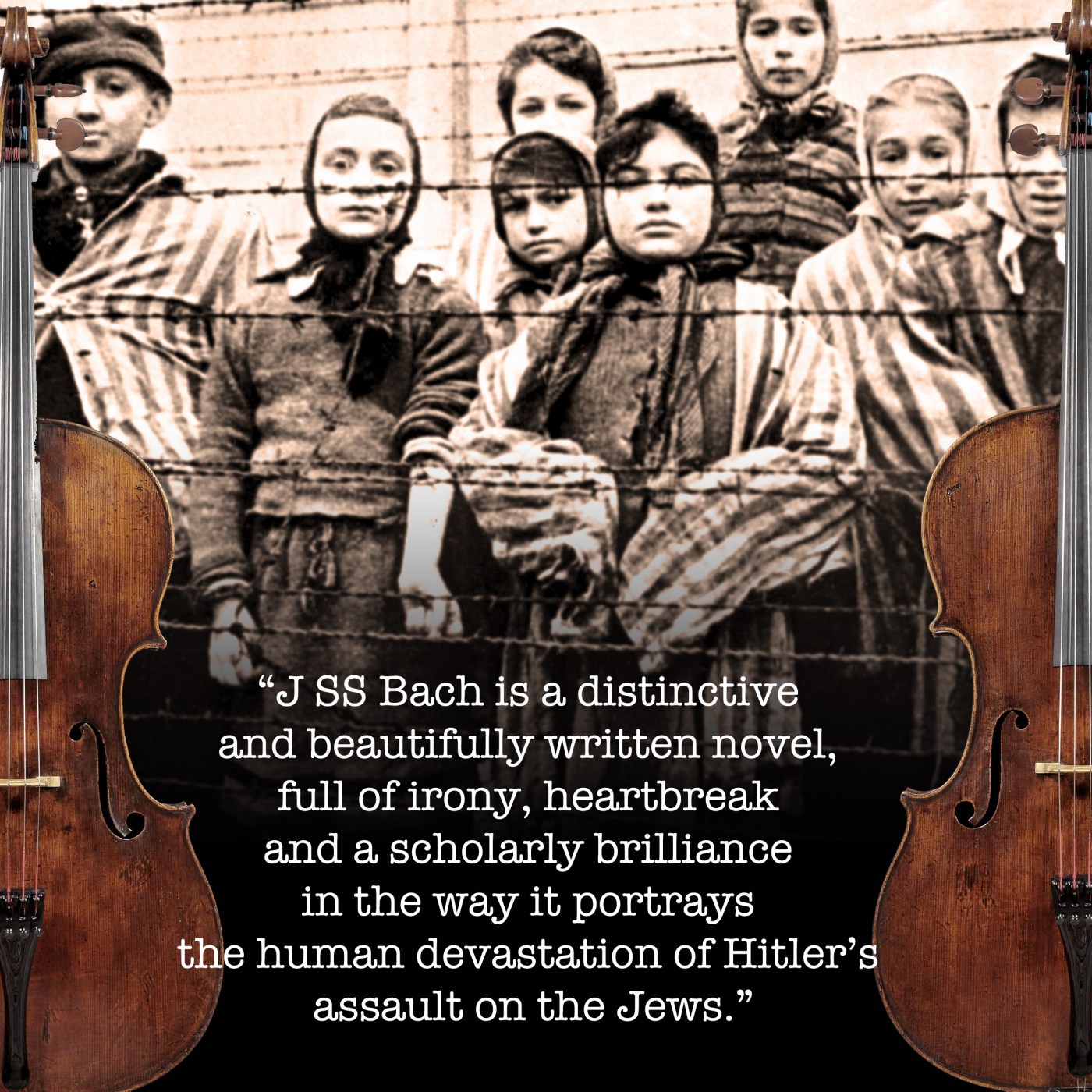

his is not a conventional crime novel. There are victims, for sure, and perpetrators of terrible acts which still, when described, take the breath away in their depravity and cold, organised manifestation of evil. English academic Martin Goodman (right)

his is not a conventional crime novel. There are victims, for sure, and perpetrators of terrible acts which still, when described, take the breath away in their depravity and cold, organised manifestation of evil. English academic Martin Goodman (right)  has written a starkly brilliant account of Nazi oppression in Central Europe in the late 1930s. He achieves his broad sweep by, paradoxically focusing on the fine detail. One family. One teenage boy, Otto Schalmek. One fateful knock on the door while Vienna and most of Austria are waving flags to welcome ‘liberation’ in the shape of the Anschluss.

has written a starkly brilliant account of Nazi oppression in Central Europe in the late 1930s. He achieves his broad sweep by, paradoxically focusing on the fine detail. One family. One teenage boy, Otto Schalmek. One fateful knock on the door while Vienna and most of Austria are waving flags to welcome ‘liberation’ in the shape of the Anschluss. The Schalmek family are Jewish. That is all that needs to be said. The family becomes just a few lines on a ledger – immaculately kept – which records the ‘resettlement’ of Jewish families. Otto is taken to Dachau and then to Birkenau. His ability as a cellist precedes him, and he is sent to play in the house of Birchendorf, the camp Commandant. His wife Katja is the artistic one, and her husband merely seeks to keep her entertained by using Schalmek as a kind of performing monkey who plays Bach suites on the cello in between sanding floors and mopping up shit in the latrines.

The Schalmek family are Jewish. That is all that needs to be said. The family becomes just a few lines on a ledger – immaculately kept – which records the ‘resettlement’ of Jewish families. Otto is taken to Dachau and then to Birkenau. His ability as a cellist precedes him, and he is sent to play in the house of Birchendorf, the camp Commandant. His wife Katja is the artistic one, and her husband merely seeks to keep her entertained by using Schalmek as a kind of performing monkey who plays Bach suites on the cello in between sanding floors and mopping up shit in the latrines. oodman’s book spans the years and the continents. Having been shown the shattering of the Schalmek family we go from the Nuremburg trials to late 1940s Canada and then, via Sydney in the 1960s, on to 1990s California, where Katja’s grand-daughter Rosa, an eminent writer and musicologist, seeks an audience with the elusive and very private genius Otto Schalmek. Rosa Cline is determined to write the definitive biography of Otto Schalmek, but their relationship takes an unexpected turn.

oodman’s book spans the years and the continents. Having been shown the shattering of the Schalmek family we go from the Nuremburg trials to late 1940s Canada and then, via Sydney in the 1960s, on to 1990s California, where Katja’s grand-daughter Rosa, an eminent writer and musicologist, seeks an audience with the elusive and very private genius Otto Schalmek. Rosa Cline is determined to write the definitive biography of Otto Schalmek, but their relationship takes an unexpected turn. is a distinctive and beautifully written novel, full of irony, heartbreak and a scholarly brilliance in the way it portrays the human devastation of Hitler’s assault on the Jews. Yes, there is the almost obligatory account of the depravity and sheer horror of the camps, but Goodman also brings a sense of great intimacy and a telling focus on the small personal tragedies and discomforts – an interrupted family meal, a tearful and hurried “goodbye”, and a new grandchild never to be cuddled by grandparents. Crime fiction? Probably not, in the scheme of things. Thrilling, often painful, and full of psychological insight? Certainly. J SS Bach is published by

is a distinctive and beautifully written novel, full of irony, heartbreak and a scholarly brilliance in the way it portrays the human devastation of Hitler’s assault on the Jews. Yes, there is the almost obligatory account of the depravity and sheer horror of the camps, but Goodman also brings a sense of great intimacy and a telling focus on the small personal tragedies and discomforts – an interrupted family meal, a tearful and hurried “goodbye”, and a new grandchild never to be cuddled by grandparents. Crime fiction? Probably not, in the scheme of things. Thrilling, often painful, and full of psychological insight? Certainly. J SS Bach is published by

I’m a great fan of historical crime fiction, particularly if it is set in the 19th or 20th centuries, but I will be the first to admit that most such novels tend not to veer towards what I call The Dark Side. Perhaps it’s the necessary wealth of period detail which gets in the way, and while some writers revel in the more lurid aspects of poverty, punishment and general mortality, the genre is usually a long way from noir. That’s absolutely fine. Many noir enthusiasts (noiristes, perhaps?) avoid historical crime in the same way that lovers of a good period yarn aren’t drawn to existential world of shadows cast by flickering neon signs on wet pavements. The latest novel from RN Morris, The White Feather Killer is an exception to my sweeping generalisation, as it is as uncomfortable and haunting a tale as I have read for some time.

I’m a great fan of historical crime fiction, particularly if it is set in the 19th or 20th centuries, but I will be the first to admit that most such novels tend not to veer towards what I call The Dark Side. Perhaps it’s the necessary wealth of period detail which gets in the way, and while some writers revel in the more lurid aspects of poverty, punishment and general mortality, the genre is usually a long way from noir. That’s absolutely fine. Many noir enthusiasts (noiristes, perhaps?) avoid historical crime in the same way that lovers of a good period yarn aren’t drawn to existential world of shadows cast by flickering neon signs on wet pavements. The latest novel from RN Morris, The White Feather Killer is an exception to my sweeping generalisation, as it is as uncomfortable and haunting a tale as I have read for some time. f Morris were to have a specialised subject on Mastermind, it might well be London Crime In 1914, as the previous books in the DI Silas Quinn series, Summon Up The Blood (2012), Mannequin House (2013), Dark Palace (2014) and The Red Hand Of Fury (2018) are all set in that fateful year. Silas Quinn, like many of the best fictional coppers, is something of an oddball. While not completely misanthropic, he prefers his own company; his personal family life is tainted with tragedy; he favours the cerebral, evidence-based approach to solving crimes rather than the knuckle-duster world of forced confessions favoured by his Scotland Yard colleagues.

f Morris were to have a specialised subject on Mastermind, it might well be London Crime In 1914, as the previous books in the DI Silas Quinn series, Summon Up The Blood (2012), Mannequin House (2013), Dark Palace (2014) and The Red Hand Of Fury (2018) are all set in that fateful year. Silas Quinn, like many of the best fictional coppers, is something of an oddball. While not completely misanthropic, he prefers his own company; his personal family life is tainted with tragedy; he favours the cerebral, evidence-based approach to solving crimes rather than the knuckle-duster world of forced confessions favoured by his Scotland Yard colleagues. orris takes his time before giving us a dead body, but his drama has some intriguing characters. We met Felix Simpkins, such a mother’s boy that, were he to be realised on the screen, we would have to resurrect Anthony Perkins for the job. His mother is not embalmed in the apple cellar, but an embittered and waspish German widow, a failed concert pianist, a failed wife, and a failed pretty much everything else except in the dubious skill of humiliating her hapless son. Central to the grim narrative is the Cardew family. Baptist Pastor Clement Cardew is the head of the family; his wife Esme knows her place, but his twin children Adam and Eve have a pivotal role in what unfolds. The trope of the hypocritical and venal clergyman is well-worn but still powerful; when we realise the depth of Cardew’s descent into darkness, it is truly chilling.

orris takes his time before giving us a dead body, but his drama has some intriguing characters. We met Felix Simpkins, such a mother’s boy that, were he to be realised on the screen, we would have to resurrect Anthony Perkins for the job. His mother is not embalmed in the apple cellar, but an embittered and waspish German widow, a failed concert pianist, a failed wife, and a failed pretty much everything else except in the dubious skill of humiliating her hapless son. Central to the grim narrative is the Cardew family. Baptist Pastor Clement Cardew is the head of the family; his wife Esme knows her place, but his twin children Adam and Eve have a pivotal role in what unfolds. The trope of the hypocritical and venal clergyman is well-worn but still powerful; when we realise the depth of Cardew’s descent into darkness, it is truly chilling. Historical novels come and go, and all too many are over-reliant on competent research and authentic period detail, but Morris (right) plays his ace with his brilliant and evocative use of language. Here, Quinn watches, bemused, as a company of army cyclists spin past him:

Historical novels come and go, and all too many are over-reliant on competent research and authentic period detail, but Morris (right) plays his ace with his brilliant and evocative use of language. Here, Quinn watches, bemused, as a company of army cyclists spin past him: uinn has to pursue his enquiries in one of the quieter London suburbs, and makes this wry observation of the world of Mr Pooter – quaintly comic, but about to be shattered by events:

uinn has to pursue his enquiries in one of the quieter London suburbs, and makes this wry observation of the world of Mr Pooter – quaintly comic, but about to be shattered by events:

London, 1591. Queen Elizabeth has ruled England for over three decades, but the religious fires lit by her father and then – literally – stoked by the Catholic zealots driven on her half-sister Mary, may just be glowing embers now, but the mutual fear and bitterness between followers of the Pope and members of the English church are only ever a breath away from igniting more conflict. Just a few short miles from England’s eastern coast, war still rages between the rebels of The Seventeen Provinces of The Low Countries and the armies of King Philip of Spain.

London, 1591. Queen Elizabeth has ruled England for over three decades, but the religious fires lit by her father and then – literally – stoked by the Catholic zealots driven on her half-sister Mary, may just be glowing embers now, but the mutual fear and bitterness between followers of the Pope and members of the English church are only ever a breath away from igniting more conflict. Just a few short miles from England’s eastern coast, war still rages between the rebels of The Seventeen Provinces of The Low Countries and the armies of King Philip of Spain. This is a riveting and convincing political thriller that just happens to be set in the sixteenth century. The smells and bells of Elizabethan England are captured in rich and sometime florid prose, while Nicholas and Bianca are perfect protagonists; she, passionate, instinctive and emotionally sensitive; he, brave, resourceful and honest, but with the true Englishman’s reluctance to seize the romantic moment when he should be squeezing it with all his might. SW Perry (right) has clearly done his history homework and he takes us on a fascinating tour through an Elizabethan physic garden, as well as letting us gaze in horror at some of the superstitious nonsense that passed for medicine five centuries ago.

This is a riveting and convincing political thriller that just happens to be set in the sixteenth century. The smells and bells of Elizabethan England are captured in rich and sometime florid prose, while Nicholas and Bianca are perfect protagonists; she, passionate, instinctive and emotionally sensitive; he, brave, resourceful and honest, but with the true Englishman’s reluctance to seize the romantic moment when he should be squeezing it with all his might. SW Perry (right) has clearly done his history homework and he takes us on a fascinating tour through an Elizabethan physic garden, as well as letting us gaze in horror at some of the superstitious nonsense that passed for medicine five centuries ago. is a reference to the Rod of Asclepius, which was a staff around which a serpent entwined itself. This Greek symbol has always been associated with healing and medicine, existing even in our time as the badge of the Royal Army Medical Corps. SW Perry’s novel is published by Corvus and

is a reference to the Rod of Asclepius, which was a staff around which a serpent entwined itself. This Greek symbol has always been associated with healing and medicine, existing even in our time as the badge of the Royal Army Medical Corps. SW Perry’s novel is published by Corvus and

Note:

Note:  Also on the run is a man convicted of attempting to assassinate Queen Victoria. Sentenced to life imprisonment on the grounds that he was mad,

Also on the run is a man convicted of attempting to assassinate Queen Victoria. Sentenced to life imprisonment on the grounds that he was mad,

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth?

First up, Metropolis is a bloody good detective story. Philip Kerr gives us a credible copper, he lets us see the same clues and evidence that the central character sees and, like all the best writers do, he throws a few false trails in our path and encourages us to follow them. We are in Berlin in the late 1920s. A decade after the German army was defeated on the battlefield and its political leaders presided over a disintegrating home front, some things are beginning to return to normal. Yes, there are crippled ex-soldiers on the streets selling bootlaces and matches, and there are clubs in the city where the determined thrill-seeker can indulge every sexual vice known to man – and a few practices that surely have their origin in hell. The bars, restaurants and cafes of Berlin are buzzing with talk of a new political party, but this is Berlin, and Berliners are much too sophisticated and cynical to do anything other than mock the ridiculous rhetoric coming from the National Socialists. Besides, most of them are Bavarians and since when did a Bavarian have either wit, word or worth? Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Metropolis sees Gunther in pursuit of a Berlin Jack The Ripper who is certainly “down on whores.” Four prostitutes are killed and scalped, but when the fifth girl to die is the daughter of a well-connected city mobster, her death is a game-changer, and Gunther suddenly has a whole new world of information and inside knowledge at his fingertips. He is drawn into another series of killings, this time the shooting of disabled war veterans. Are the two sets of murders connected? When the police receive gloating letters, apparently from the perpetrator, does it mean that someone from the emergent extreme right wing of politics is, as they might put it, “cleaning up the streets”?

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

Mölbling helps Gunther disguise himself as one of the disabled ex-soldiers, as he reluctantly accepts the role in order to attract the killer who, in his letters to the cops, signs himself Dr. Gnadenschuss. Gunther’s trap eventually draws forth the predator, but not in the way either he or his bosses might have anticipated.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.

Harper lives above a city pub, the Victoria. His wife, Annabelle, is the landlady, but she is also a fiercely determined advocate of women’s rights, and she has made waves by being elected to the local Board of Guardians, a largely male-dominated organisation which is tasked with administering what, in the dying years of Queen Victoria’s reign, passed for social care. When the brother of Harper’s one-time colleague, Billy Reed, commits suicide the death is dismissed, albeit sadly, as commonplace, but Reed believes that his brother’s death is due to something more sinister, and he asks Harper to investigate.